- By Sean Brophy (@seanbrofee), Senior Lecturer at the Centre for Decent Work and Productivity, Manchester Metropolitan University.

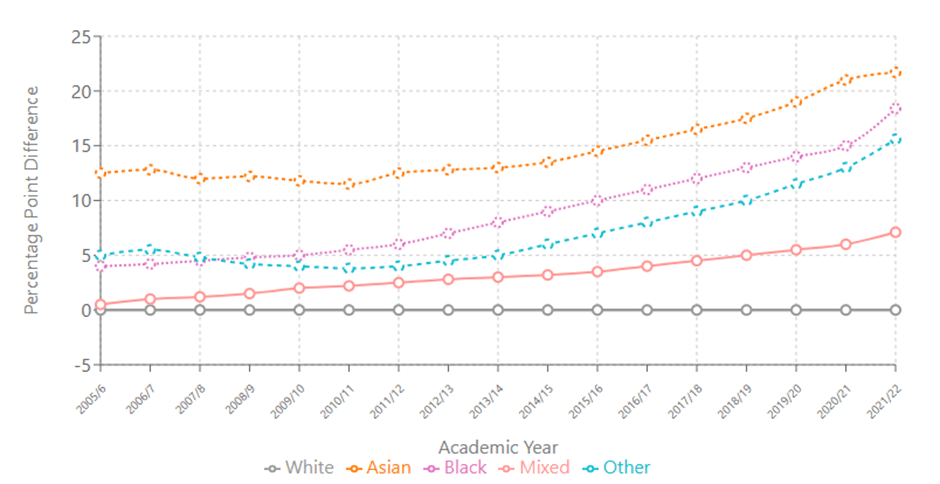

A persistent challenge in UK higher education is the ethnicity degree awarding gap – the difference between White and ethnic minority students receiving top degrees (firsts or 2:1s). The Office for Students (OfS) aims to entirely eliminate this gap by 2030/31, but what if most of this gap reflects success in widening participation rather than systemic barriers?

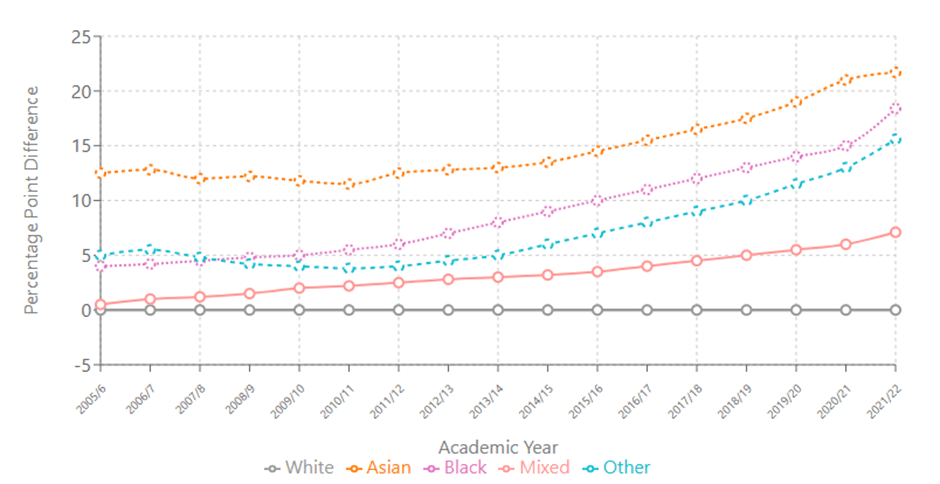

Between 2005/6 and 2021/22, university participation grew 21% faster for Asian students and 17% faster for Black students compared to White students. This remarkable success in widening access might paradoxically explain one of the UK’s most persistent higher education challenges.

Figure 1 presents ethnicity gaps over time compared to a White baseline (the grey line constant at zero). The data for 2021/22 shows significant gaps: 21 percentage points for Black students, 9 for Asian students, and 4 for Mixed ethnicity students compared to their White peers. Traditional explanations focus on structural barriers, cultural differences, and potential discrimination, and much of the awarding gap remains unexplained after adjusting for prior attainment and background characteristics. However, a simpler explanation might be hiding in plain sight: the gap may also reflect a statistical effect created by varying participation rates across ethnic groups.

Ethnicity Degree Awarding Gap (2014/15 – 2021/22)

Here is the key insight: ethnic minority groups now participate in higher education at remarkably higher rates than White students, which likely then drives some of the observed ethnicity awarding gaps. Figure 2 presents the over-representation of ethnic groups in UK higher education relative to the White reference group (again, the constant grey line). The participation gap has grown substantially – Asian students were 22 percentage points more likely to attend university than White students in 2021/22, with Black students 18 points higher.

Over-representation of ethnic groups in HE compared to White baseline (2005/6-2021/22)

This difference in participation rates creates an important statistical effect, what economists call ‘compositional effects’. When a much larger proportion of any group enters university, that group may naturally include a broader range of academic ability. Think of it like this: if mainly the top third of White students attend university, but nearly half of ethnic minority students do, we would expect to see differences in degree outcomes – even with completely fair teaching and assessment.

This principle can be illustrated using stylized ability-participation curves for representative ethnic groups in Figure 3. These curves show the theoretical distribution of academic ability for Asian, Black, and White groups, with the red shaded area representing the proportion of students from each group accepted into higher education in 2021/22. It would be surprising if there was no degree awarding gap under these conditions!

Stylized ability-participation curves by ethnic group

This hypothesis suggests the degree awarding gap might largely reflect the success of widening participation policies. Compositional effects like these are difficult to control for in studies, and it is noteworthy that, to date, no studies on the ethnicity awarding gap have adequately controlled for these effects (including one of my recent studies).

While this theory may offer a compelling statistical explanation, future research pursuing this line of inquiry needs to go beyond simply controlling for prior achievement. We need to examine both how individual attainment evolves from early education to university, using richer measures than previous studies, and how the expansion of university participation has changed the composition of student ability over time. This analysis must also account for differences within broad ethnic categories (British Indian students, for example, show different patterns from other Asian groups) and consider how university and subject choices vary across groups.

My argument is not that compositional effects explain everything — rather, understanding their magnitude is crucial for correctly attributing how much of the gap is driven by traditional explanations, such as prior attainment, background characteristics, structural barriers, or discrimination. Only with this fuller picture can we properly target resources and interventions where they’re most needed.

If this hypothesis is proven correct, however, it underscores why the current policy focus on entirely eliminating gaps through teaching quality or support services, while well-intentioned, may be misguided. If gaps are the statistically inevitable result of differing participation patterns among ethnic groups, then institutional interventions cannot entirely eliminate them. This doesn’t mean universities shouldn’t strive to support all students effectively – but it does require us to fundamentally rethink how we measure and address educational disparities.

Rather than treating all gaps as problems to be eliminated, we should:

- Fund research which better accounts for these compositional effects.

- Develop benchmarks that account for participation rates when measuring degree outcomes.

- Contextualize the success of widening participation with acknowledging awarding gaps as an inevitable statistical consequence.

- Focus resources on early academic support for students from all backgrounds who might need additional help, particularly in early childhood.

- Explore barriers in other post-16 or post-18 pathways that may be contributing to the over-representation of some groups in higher education.