When I was maybe 10 or 11 I remember going on a trip to Jodrell Bank. It was huge, and quite a lot of the material must have been out of my comprehension, but I recall being fascinated by the ticker tape with which they recorded the data received by the telescope.

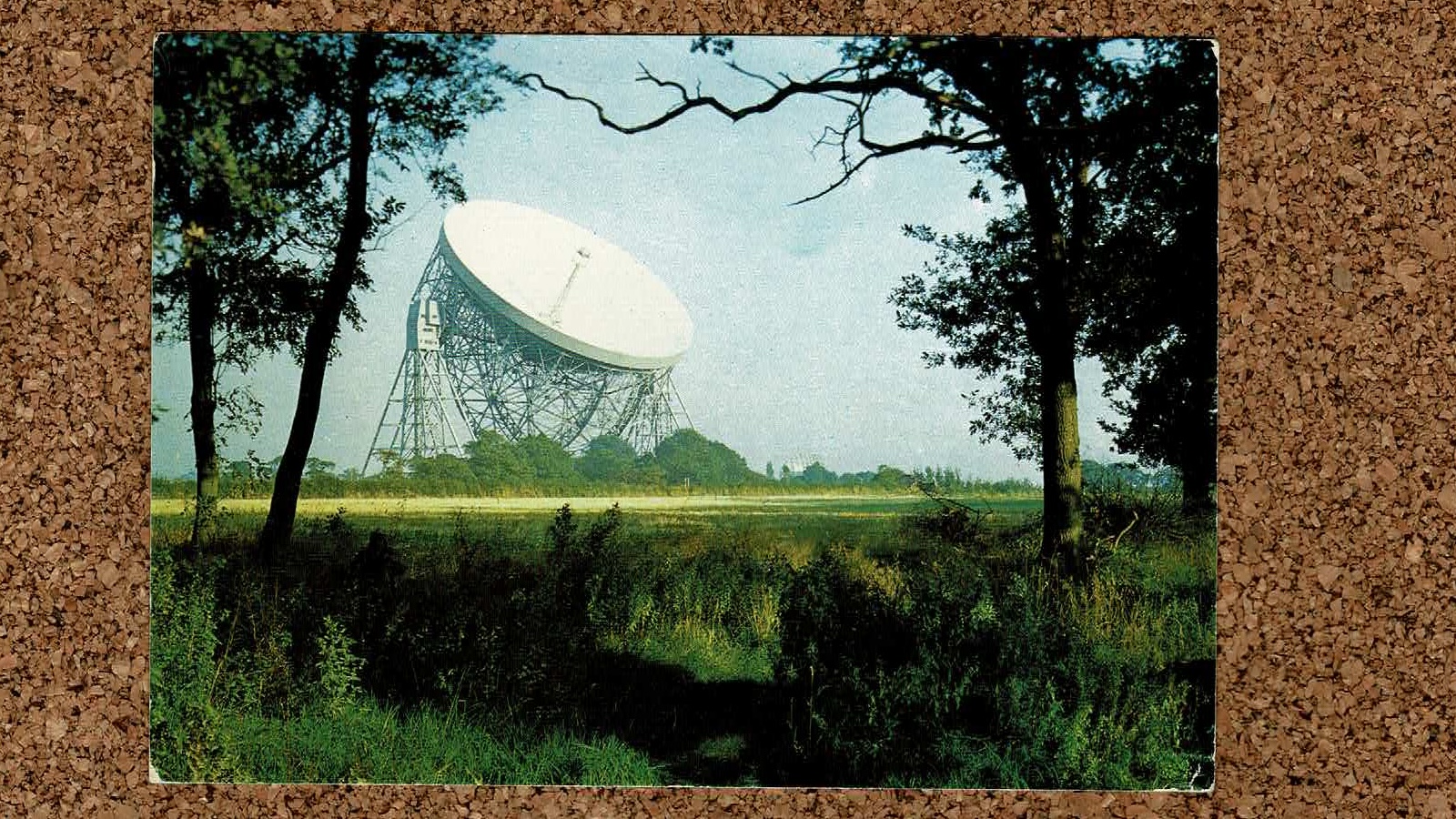

Anyway, welcome to Cheshire. What you can see on the card is the Lovell Telescope – not an optical telescope but one which uses radio waves to explore the universe. The facility is part of the University of Manchester, which is how it qualifies for this write up.

The telescope’s story begins in 1945, but we need to go a bit further back for context. So, first, how is this a telescope? Where do you put your eye? Well, it’s a radio telescope: rather than using the visible spectrum it looks for radio waves. There’s a good explainer video here – worth a few minutes of your time. And the telescope on the card makes an appearance at about 2:20.

Radio astronomy was discovered in 1933 by Karl Jansky, an American telecoms engineer who was trying to work out why there was a background hiss on short wave transmissions. His discovery of radio waves coming from the Milky Way paved the way for others. In 1937 an amateur astronomer, Grote Reber, built a radio telescope with a nine metre wide dish in his backyard, confirmed Jansky’s results, and demonstrated that radio astronomy was feasible.

(Just stop and read that again. An amateur astronomer. A nine-metre diameter dish. A new field of science. What a life!)

And now we can come closer to home. Bernard Lovell – after whom the telescope is now named – was an astronomer studying cosmic rays. After World War 2 (during which he had been working on radar for the UK government) he returned to his research on cosmic rays at the University of Manchester. But the electric cables for the Manchester trams interfered with his equipment, so he took his rig to a field station in Cheshire, owned by the university and used by its botany department. And got much better signals. He’d discovered meteors, though, not cosmic rays. And this got him and his fellow scientists very interested.

The field station became known as the Jodrell Bank Experimental Station. A team grew, building and installing steadily more powerful instruments. Lovell teamed up with a civil engineer from Sheffield, Charles Husband (the son of the founder of the University of Sheffield’s civil engineering department). They designed a 250ft diameter radio telescope that could be pointed at any point in the sky above Cheshire, and work commenced in 1952 to build it.

This drawing of the telescope, published by the Manchester Evening News on 10 June 1954 shows how it had captured the public imagination.

Anyone familiar with university capital projects will not be surprised to learn that there were delays, cost overruns and building problems, and by 1957 the future of the uncompleted-but-partly-operational telescope was uncertain. But when the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1, the UK government realised that it would be quite handy to be able to track fast moving objects in space. And the telescope at Jodrell Bank was the only instrument in the world able to do it. Money was found, problems solved, and the telescope – then called the Mark 1 telescope – was completed and became fully operational.

Jodrell Bank then began a dual life. As a fully-functioning scientific telescope, contributing tremendously to our knowledge of the galaxy, its formation and the different phenomena in it. And also as a secret military establishment, part of the UK’s early warning system for attack by ballistic missiles, and also used in tracking space activity by NASA and the Soviet Union.

It is still a functioning and useful telescope, although advances in our understanding of radio astronomy mean that distributed arrays of smaller telescopes are now preferred – more powerful and easier and cheaper to run.

The telescope was renamed the Lovell Telescope in 1987, and was given grade 1 listed building status the following year (can you imagine the challenges in maintaining a piece of scientific equipment which is heritage listed?). The whole site was named as a UNESCO world heritage site in 2019. And it is well worth a visit! The website for the centre has an excellent short history, on which I have drawn for some of this blog, which is also well worth a visit, not least for the great images.

Here’s a jigsaw of the card. It hasn’t been posted, but looks to be from the 1960s. It tells us on the back that

the 250 ft Radio Telescope is the major instrument belonging to the Department of Radio Astronomy [of the University of Manchester]. It is set in the rural county of Cheshire, about 20 miles south of Manchester.