by Anu Lainio and Anna Sofia Salonen

“I also feel that the sense of hopefulness…is essential. Without it there isn’t much concrete to hold on to. At least I see that this kind of outlandish dreaming and utopian imagining is, in a certain way, also reflected in the actions taken toward it. Or that nothing moves anywhere if you don’t envision it.”

This quotation illustrates how a group of higher education students understood outlandish dreaming as essential for social and political change. It also connects directly to our main argument: that political imagination is a form of political agency. The shared recognition in the quote, that imagining itself matters, shows how utopianising is potentially already a political act.

Political imagination can be characterised as a collective and open-ended process of envisioning how the world and ourselves could be otherwise. Utopias, in turn, are tools for political imagination. Together, political imagination and utopias expand the horizon of what can be thought of as possible and desirable.

The scholarship on students’ political agency has mainly explored traditional and conventional forms of political participation, such as protests, student governance, and voting behaviour. Yet, political agency is not limited to these forms of participation; it also takes place in various everyday practices. By studying political imagination, we can explore how students relate to politics in everyday life: how they think, feel, speak, and act politically.

We explored higher education students’ political imagination as part of an ongoing project, Breadline Utopias. We invited students from social sciences, education, social services, and healthcare to participate in workshops on alternative futures of food assistance. These students are likely to work in roles connected to food assistance (directly and indirectly), which makes their perspectives especially relevant. Altogether, 86 students participated in seven workshops across four higher education institutions. Our analysis draws on 21 small-group discussions in which students discussed the current state of food assistance and imagined alternative futures for it.

Food assistance in Finland is a contested practice that sits between Nordic welfare state ideals and charity-based logics. Over the last 30 years, it has become an institutionalised part of Finnish society. Because food assistance is intertwined with broader societal issues, such as poverty, justice, food, and social policy, it offers a rich site for examining how students navigate and relate to political questions.

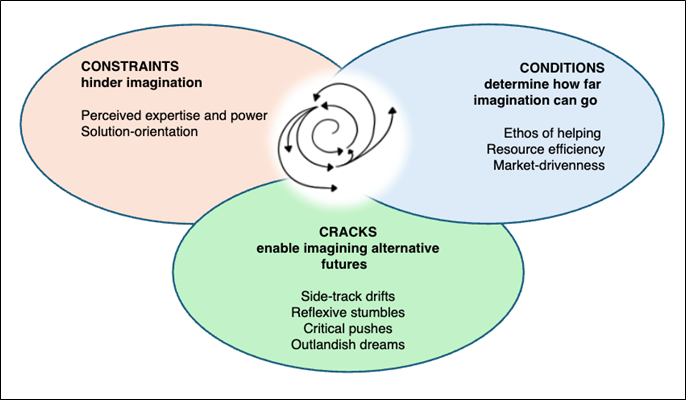

Constraints, conditions and cracks of political imagination

Our research shows that political imagination is shaped by a dynamic between three elements: constraints, conditions and cracks. This dynamic suggests that political imagination is a fragile yet meaningful mode of political agency.

Constraints block imagination

Constraints are moments where students’ political imagination becomes blocked. They act as barriers for imagination – like the dead-end of a labyrinth. Constraints relate to who is seen as able to imagine and what legitimate imagining should look like. For example, some students felt that they don’t have the “right” knowledge or experience to envision alternative futures for food assistance. As one student put it:

“Since I’m not an expert on the issue at all, it’s [difficult] to predict it or to develop it in general, because I’ve never been part of it myself.”

This lack of perceived expertise reduces students’ sense of agency, leading them to position themselves outside the political sphere. Another constraint, solution-orientation, also blocks political imagination. With this mindset, societal questions are approached as technical problems to be fixed, reflecting an internalised sense of what kinds of discussions are acceptable and meaningful.

Conditions limit imagination

Conditions shape what students imagine by acting as boundaries that limit how far imagination can extend toward contesting taken-for-granted logics of the topic in question. We identified three conditions: the ethos of helping, resource efficiency, and market-drivenness. All three stem from the charity economy frame, which means that students’ visions focused on improving helping practices, maximising existing resources (volunteers, surplus food and money) or finding market-compatible solutions. Within these boundaries, both food assistance and poverty are depoliticised, as imagination remains anchored to the existing system rather than questioning or transforming it.

Cracks reveal fractures and open up alternatives

Cracks are moments that reveal fractures in the current system and in students’ experiential worlds: openings through which alternative futures become visible or thinkable. Cracks took different forms in students’ discussions. At times, conversations drifted onto sidetracks that disrupted linear and solution-oriented talk, allowing new questions and possibilities to surface. In other moments, students paused to consider the perspectives of food assistance recipients. Such reflexive stumbles invited empathy, vulnerability and relational awareness, opening space for politicisation. There were also critical pushes in which seemingly neutral features of the system were recognised as politically constructed. These instances opened cracks through which alternative social and institutional arrangements were imagined. Finally, as the quotation in the beginning shows, outlandish dreams are moments when students collectively affirm that hope and utopias themselves matter, even though the process of imagining alternatives is difficult and involves constraints and conditions.

Political imagination as a democratic capacity

The dynamic between constraints, cracks and conditions highlights that ‘the political’ in political imagination appears unevenly – sometimes blocked, sometimes strengthened, sometimes catalysed. Thus, political imagination is not a linear process but unfolds within the dynamics of these three elements (see Picture 1). Despite its fragility, we suggest that political imagination is a meaningful mode of political agency: it is visible in how students critique existing conditions, propose alternative futures and reposition themselves in relation to the political. Political imagination makes the openness of the future visible. It is precisely this openness that gives imagination its value as a form of agency: it keeps the alternative futures alive.

Picture 1. Constraints, conditions and cracks of political imagination

Recognising these everyday acts of imagining as political practices expands our understanding of what counts as students’ political agency. In doing so, it points to political imagination as a capacity for democratic citizenship, as the ability to envision alternatives is integral to democratic life. This capacity is all the more important given reports of young people’s reduced hope for the future and the global challenges we are facing (e.g., polarisation and climate change). Cultivating such capacity should be part of higher education’s democratic mission. In other words, outlandish dreaming is not trivial or escapism – it is a fragile, necessary political act.

Dr Anu Lainio works as a Postdoctoral researcher at the University of Eastern Finland. Her research focuses on higher education students’ political imagination and utopias, as part of the project ‘Utopias from the breadline’. Before her current position, she completed her doctoral research at the University of Surrey, UK, where she explored higher education students’ identities and media representations across different European countries. Her research interests include political imagination; media and higher education; and student identities, agency, and (in)equalities in the context of marketised higher education and a changing welfare state.

Dr Anna Sofia Salonen is a University Lecturer in Practical Theology at the University of Eastern Finland. Her research combines sociological and theological perspectives to explore issues related to food, religion, ethics, inequality and the food system. She is the principal investigator of the research project “Utopias from the breadline” (Kone Foundation 2023-2025) and leads a work package on nonreligion in research project “Religion, Meaning and Masculinity” (Research Council of Finland 2024-2028).