This blog was authored by Rose Stephenson, Director of Policy and Strategy at HEPI.

In under 12 months’ time, the first cohort of students in England will begin studying courses under the Lifelong Learning Entitlement (LLE).

The LLE will work as follows:

- For new learners, the LLE will provide a maximum tuition fee loan equal to four years of study.

- For returning learners, the amount they can borrow will be reduced depending on the funding they have previously received to support study.

- Maintenance loans and other forms of financial support will also be available, depending on individual circumstances.

- Learners will be able to see their loan balance through their own LLE personal account, hosted by the Student Loans Company.

- This entitlement will replace the current higher education student finance loans and Advanced Learner Loans for Levels 4, 5 and 6 qualifications.

This streamlines the post-18 student finance system. So far, so good.

Where it gets a little trickier is this:

As with the previous finance system, learners can take out a loan for a full qualification; a degree or a higher technical qualification (HTQ) such as a Level 4 higher national certificate (HNC) or a Level 5 higher national diploma (HND).

However, from January 2027, learners will also be able to take out a loan for:

- A module or modules from an HTQ course (such as a 30-credit module of an HNC)

- A module or modules from a full Level 6 qualification (such as a 30-credit module of a degree), providing this degree aligns with the Government’s priority skills needs or Industrial Strategy.

Loan-based funding for modular higher education study requires a significant change to infrastructure and practice in the sector, and this blog will consider whether these elements are in place to support a concerted move towards modular-based provision.

In 2021, the Office for Students (OfS) launched the higher education short course trial. (You can read more about this in a previous HEPI blog, here.) It was anticipated that 2,000 learners would take part in this trial. Ultimately, only 125 students took part, and only 41 students took out a loan to access their short-course.

The trial was evaluated by the Careers Research and Advisory Centre (CRAC) which found that:

- There was a lack of clarity on who the target audience was.

- There was a lack of public awareness of the availability of short courses.

- The lack of an accepted credit transfer mechanism between institutions led to a reduction in the perceived value of modules.

- The application process for taking out loans for a short course was cumbersome.

- There were challenges with the curriculum development of 30-credit modules. This is not, of course, as straightforward as simply chopping a degree into modules.

- Institutions faced financial challenges in recruiting and onboarding students for such a small return.

The evaluation report for this trial was published in January 2024. So, what has changed in the past two years? Are we any more ready for modular learning than we were then?

For the modular element of the LLE to be a success, the following needs to happen:

- The general public needs to be aware of the LLE.

- Modular regulation needs to be robust, risk-based and not lead to institutional disadvantage for trailblazers of this policy.

- Learners need to be able to see which modules are available to them

Let’s look at each of these issues independently.

Are the general public aware of the LLE?

One of the issues outlined by the short-course trial was the lack of public awareness of the availability and value of short courses.

To understand whether this had changed in the run-up to the LLE, we posed a survey question:

Are you aware of the Lifelong Learning Entitlement? (This is the new method for student loan funding in England, which will come into force in 2027. You will be able to access the equivalent of four years’ worth of student loan funds – minus loans already taken – to use on short courses or modules as well as full qualifications.)

The research was conducted by Savanta using an online panel of UK respondents. Data were collected as part of a UK-wide omnibus survey between 16th and 19th January, with an overall sample size of 2,126. Data was weighted to be representative of the UK population by age, gender, region and social grade. A screening question was then applied to select respondents living in England, resulting in 1,857 respondents for our question.

Figure 1 shows the overall results. Only 12% of the adult population of England are aware of the entitlement.

There are some caveats to be applied here. First, as the LLE provides loans from Levels 4 to 6, it would be reasonable to expect that applicants may have previously gained a Level 3 qualification. Unfortunately, we could not cut the data to determine awareness based on previous qualification. However, even for learners who are yet to obtain a Level 3 qualification, awareness of the LLE may be advantageous to qualification and career planning.

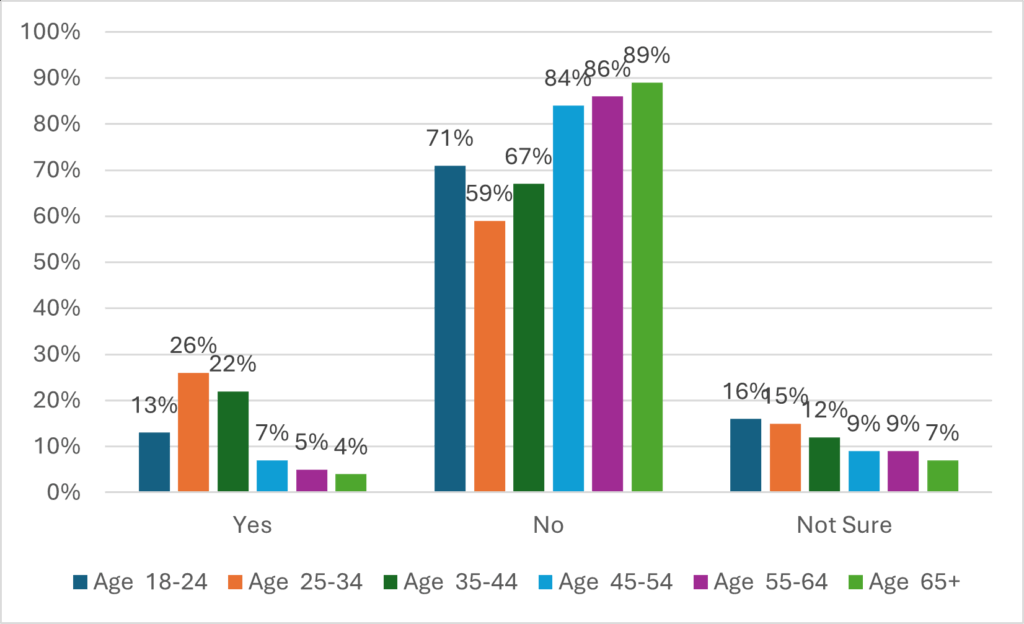

Secondly, this omnibus survey covers all adults over the age of 18, and the LLE is only applicable for those up to the age of 60. The data can be analysed by age. Figure 2 demonstrates that 13% of those aged 18 to 24 are aware of the LLE. This is concerning, given that around half of these people will be passing through the higher education system now or soon. However, many in this age bracket will already be undertaking a higher education qualification and will be likely to complete it under the previous system. There is a higher level of awareness among 25- to 34-year-olds (26%) and 35- to 44-year-olds (22%). Awareness then drops off steeply from those aged 45 and over.

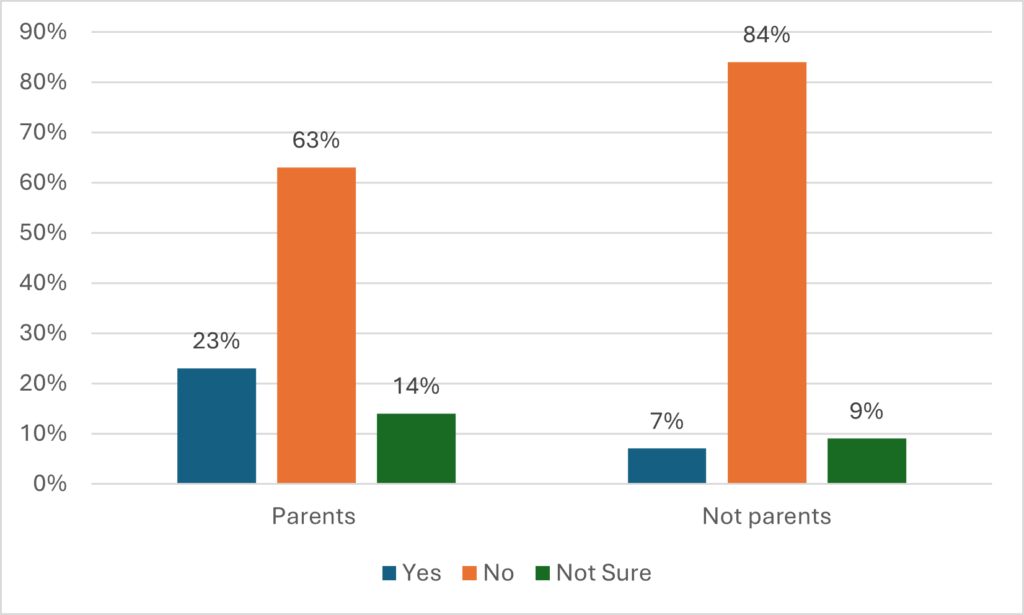

The data could also be analysed by parental status. The definition of ‘parent’ in this survey is anyone with a child under the age of 18. Figure 3 shows that almost a quarter of parents (23%) are aware of the LLE, compared to only 7% of those who are not parents. There is an overlap with the responses by age.

It is unclear from the data whether parents are more aware of this information because it will affect their children, or whether the ‘parents-of-children’ cohort is at a stage where they themselves are considering upskilling or retraining, or a combination of both.

There is also nuance in the data in that respondents in London are much more likely to be aware of the LLE; 27% of London-based respondents are aware of the LLE compared with 12% across England as a whole. London regularly seems to exist in its own, very successful, educational ecosystem. So perhaps this is due to higher participation rates in London, or the possible higher rates of job mobility in the capital.

Can learners find modular provision?

Alongside the issue of awareness is the related conundrum of how learners will find flexible, modular courses. UCAS have stated that their platform will not be covering the modular course offer ahead of 2027, although they are laying foundations that may allow for this in the future.

Instead, students will need to search for these courses on an institution-by-institution basis. Institutions that met the criteria for offering modular provision (registered with the OfS, TEF gold or silver or an Ofsted rating of ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’) could submit an expression of interest to the Department for Education, which has been undertaking assurance processes. However, the Department for Education will not be releasing the list of successful providers until the summer of 2026. So, while applications will open in September, but potential learners will really struggle to undertake any research into course choice before this date.

The LLE launch has been purposefully designed as a ‘soft-launch’, with restrictions on providers and courses offered, and this is arguably a sensible approach. But the additional lack of infrastructure and awareness-raising makes this feel more like a ‘quashed launch’, limiting students’ ability to engage with an educational offer that has such potential.

What might modular regulation look like?

It is important to remember the original policy intent of the LLE, which was described in a DfE press release in 2023 as:

Like a flexi-travel card, it allows people to jump on and off their learning, as opposed to having a ticket with a single destination.

For providers to embrace the LLE, the regulation of modular provision must be clear. However, the details of modular regulation have not been released by the Office for Students (OfS), who told me:

We expect to publish further guidance and detailed regulatory information in early 2026, giving providers sufficient time to prepare ahead of implementation in January 2027.

Institutions will not proceed with the LLE if this puts their regulated outcome measures at risk. Given that providers needed to submit an expression of interest to the DfE by October last year, publishing guidance well after this deadline does not give providers sufficient time to prepare.

So, how might modular regulation work, and why might this cause an issue for providers?

The OfS also explained:

We anticipate that providers offering LLE-funded modules will be regulated in the same way. We do not expect to introduce a separate regulatory framework specifically for modular provision.

This makes sense in terms of the broad conditions of registration for institutions. However, for the specific metrics used for regulation, including the B3 measures such as continuation and completion of a qualification, it is unclear how this could be the case.

If students are divided into three ‘buckets’, this highlights the challenge:

- Bucket One: Students who sign up for a full qualification.

- Bucket Two: Students who want to complete a full qualification, but in a more flexible manner – let’s say a typical undergraduate degree over six years rather than three.

- Bucket Three: Students who want to take standalone modules.

Continuation and completion and progression won’t apply to students in Bucket Three undertaking standalone modules – at least not in the same ways as students in Bucket One. Further, in many cases, students in Bucket Two will be considered ’non-completers’ under the current metrics.

This poses the question of whether students will have to define which bucket they want to be in when they sign up for their course? However, this would undermine the entire LLE policy – all the students in Bucket One would have zero flexibility – or at least their institution would risk incurring regulatory penalties if it facilitates or encourages this level of flexibility. And it would be unfair, for example, for a Bucket Two student to be able to complete their modules over a longer period, but Bucket One students on the same course could not.

However, if students are allowed to move buckets, then the concept of completion for a full degree is null and void. If a student can choose to move from Bucket One to Bucket Two or Three (and this should be a legitimate choice under a well-implemented LLE policy), then the concept of non-completers as a negative outcome no longer exists. A student is simply choosing to finish or pause their education after one module, or when they reach a Level 4 or 5 qualification in their subject.

Institutions that are considering offering modular provision are planning to open these modules for application in September, in just eight months’ time. Yet how they will be judged by the regulator for doing so remains unclear.

Conclusion

It’s pleasing to see that several institutions are preparing to champion the LLE. This includes the colleges and universities that have taken part in the Modular Acceleration Programme (MAP) offering modular provision of higher technical qualifications and providers like University Centre Peterborough who are actively working towards the launch in 2027.

However, this feels like a classic case of a high-potential, well-intentioned policy without the thought or investment in on-the-ground implementation. For the LLE to meet its promise, there must be more awareness, greater transparency and increased incentives (such as the MAP trial) for both students and institutions.