Two hundred years and two days ago (at least if this is published on 13 February 2026, as I expect, and if my counting is right, which I hope it is), the first governing council of what became UCL was established. We’ve visited UCL before, for an Esperanto conference, but in commemoration of its bicentennial, let’s have a closer look at the early years.

I’m drawing on the very thorough and much-less-dry-than-you’d-expect University College London 1826–1926, by Hugh Hale Bellot, professor of American history at the University of London from 1930 and its vice chancellor between 1951 and 1953. He was also played a leading role in the Institute of Historical Research: here’s a short obituary and note of appreciation published in the institute’s journal.

Poet’s corner

There’s obviously an awful lot to cover here, so I’m just going to pick out a few aspects. And I think we have to start with Thomas Campbell. He’s a Scottish poet who I confess I hadn’t heard of, but who appears to have been significant in the romantic movement. He was also – and perhaps necessarily – a man of ideas: “a dreamer of dreams”, as Hale Bellot remarks, but “dependent upon others for the realisation of his plans.” Inspired by the newly founded Rhein-Universität Bonn, and no doubt by the contrast in culture between Oxbridge and the Scottish ancient universities, Campbell wrote an open letter to Henry Brougham in February 1825 proposing the creation of a metropolitan university. He followed this up shortly after with a longer piece, reproduced here, which sought to flesh out the idea somewhat.

Essentially, his argument was this: Oxbridge was expensive to attend; inaccessible to many, because of religious tests; and also did not provide a useful education. There was room, therefore, for a university in London, which addressed sciences, law and other subjects beyond the classics of Oxford and Cambridge, and which would be funded by fees. The argument found favour – Hale Bellot notes that there was a ferment of progressive ideas about education at that time, but no effective vehicles for change – and soon subscriptions were invited for shares in a company to establish this university. The hope was to raise about £150,000: this would pay for the buildings, and provide working capital for the new university (it’s equivalent to about £12.3m in today’s money).

Fairly obviously, most poets would find it difficult on their own to raise funds like that for a university, and let’s not forget – again in Hale Bellot’s words – that Campbell “had no capacity for that sustained attention to detail which is necessary to the translation of an idea into an institution.” So we need now to turn to the person to whom Campbell addressed his letter: Henry Brougham.

The committee

Brougham was clearly an ambitious man with connections. In part due to his influence a provisional committee was established, which arranged a share offer, debated policies, arranged for legal steps to be taken, and generally drove the matter forward. In September 1825 land was brought in anticipation, and later transferred to the company. This was a plot in what was then the suburbs of London, bought for £30,000 from a developer who had bought it at auction less than a year previously, and made £7,950 profit from the exchange.

The first council had Whig politicians; dissenters and Catholics who were prevented from attending Oxbridge; educational radicals such as George Birkbeck; utilitarian philosophers; and protestant evangelicals. It was a coalition of very different interests, and there was a lot of arguing.

Gods and monsters

UCL was famously called the godless institution on Gower Street. This referred to the lack of a religious test: at Oxford and Cambridge students were required to affirm, before they could graduate, that they subscribed to the core beliefs of the Church of England. This meant that those following other religious beliefs (such as Methodists, Baptists and other dissenters, Catholics and, presumably, followers of non-Christian religions too) were, effectively, barred from those universities. (The religious requirements were not removed from Oxford, Cambridge or Durham until 1871, with the passing of the Universities Tests Act.)

But do not be deceived into thinking that UCL was an atheist creation. Some of the proponents no doubt were religious freethinkers, but many were deeply religious. The argument about whether to provide for religious worship at UCL, and whether to teach divinity, occupied a lot of time. Eventually, the decision was made that the new university would not teach any religion, nor would it provide directly for any form of worship, via a chapel or similar. This was facilitated by, or perhaps required, that the new university didn’t provide any residential accommodation for students. (This was also a cost factor, so to my mind it is about arrangements that supported each other rather than the religious issue being the dominant factor.)

The end result was a radical position: religious observance was, so far as the new university was concerned, a private matter not a public matter. Students were not required to make any profession of any creed as part of their studies. Staff were not teaching divinity, and therefore no question of the superiority of one set of religious beliefs over another could arise as part of the curriculum. And the university would not directly provide facilities for any religion. But equally some sects provided for churches and chapels nearby, and arranged for services for students who wanted to join in, away from the university’s premises. The “godless” institution was areligious not irreligious.

The funds raised by February 1825 amounted to £156,749. And spending on the buildings, on furniture, apparatus and the library, amounted to £143,323. Which didn’t leave a lot of working capital. When the college admitted the first students in autumn 1828 the new university was – like many in higher education today – managing on fee income directly, and, it seems making guarantees to professors of future income rather than paying them directly. (A note to any vice chancellors reading this today and thinking that they could pay staff by IOU. No. This is not a good way to do things. I’m no lawyer but I bet it counts as breach of contract. Do not even think of it.)

And here’s a plan of the original building from 1828, and as it changed over the fifty years or so. I haven’t been able to track down much on the fire of 1836 – maybe that’s for another blog – but note that there was a school as well as the university. If you’re familiar with UCL, how much of this do you recognise? Is the semi-circular lecture theatre top right on the first floor what is now the Gustave Tuck theatre?

Degrees of success

Finally, we need to look at how the joint stock company called the University of London became University College London; and how a University of London came to be given a charter. There’s a lot of moving parts here, and it’s a topic on which much history has been written. So this summary will undoubtedly gloss over some important things, but I will do my best.

Firstly, we need to look at the broader environment. In England and Wales, in 1825, only Oxford and Cambridge universities could award degrees. (In Scotland there were four universities; in Ireland, which at that time was wholly part of the British Empire, Trinity College Dublin was the ancient university.) Medical education was on the way to being regularised, but was still very much the concern of the Royal Colleges.

But things were changing. Durham University was established in 1832 and chartered in 1837; and it was very much cast from the same mould as Oxford and Cambridge: collegiate, establishment, church. St David’s Lampeter was established in 1828 and given a charter, to train ministers for the church. And King’s College London was founded as a counterbalance to the new University of London: and like Durham it was establishment and church. Given all of this, it was hard to ignore the claims of the new university of Gower Street. But Oxbridge opposed the granting of degree awarding powers to a London institution, especially one like the radical new university. And the medical establishment wasn’t keen either.

Being aware of this, the new university, in petitioning for a charter or act of parliament to give it a more solid legal basis as a corporation, had been clear that it did not want degree awarding powers. But this was a tricky argument to make: was a degree not an important thing to recognise students’ knowledge and achievement? And wouldn’t the absence of degree awards act as a disincentive to students?

A change in government – and a Whig premiership – made it possible to move the matter forward, but again it took much deliberation. The solution agreed upon was indeed to create a University of London which could award degrees. But it wasn’t to be based upon the institution founded in Gower Street. And so, on 28 November 1836, a charter was granted to University College London, as the institution now became named. And the following day a charter was granted establishing a University of London, which would examine students of University College London, King’s College London and other institutions, and award degrees to those who passed the examinations.

And that’s how we got from a poet’s agitation for a new approach to university education in London, to an actual university in London, with actual colleges, and a structure unique for the time. Even though the first ten years were eventful, and its name as UCL dates from 1836, UCL dates its establishment from the establishment of the Council of the University of London in 1826. And I think, for what it is worth, that this is very justifiable.

And so happy anniversary, UCL. Here’s to the next 200 years!

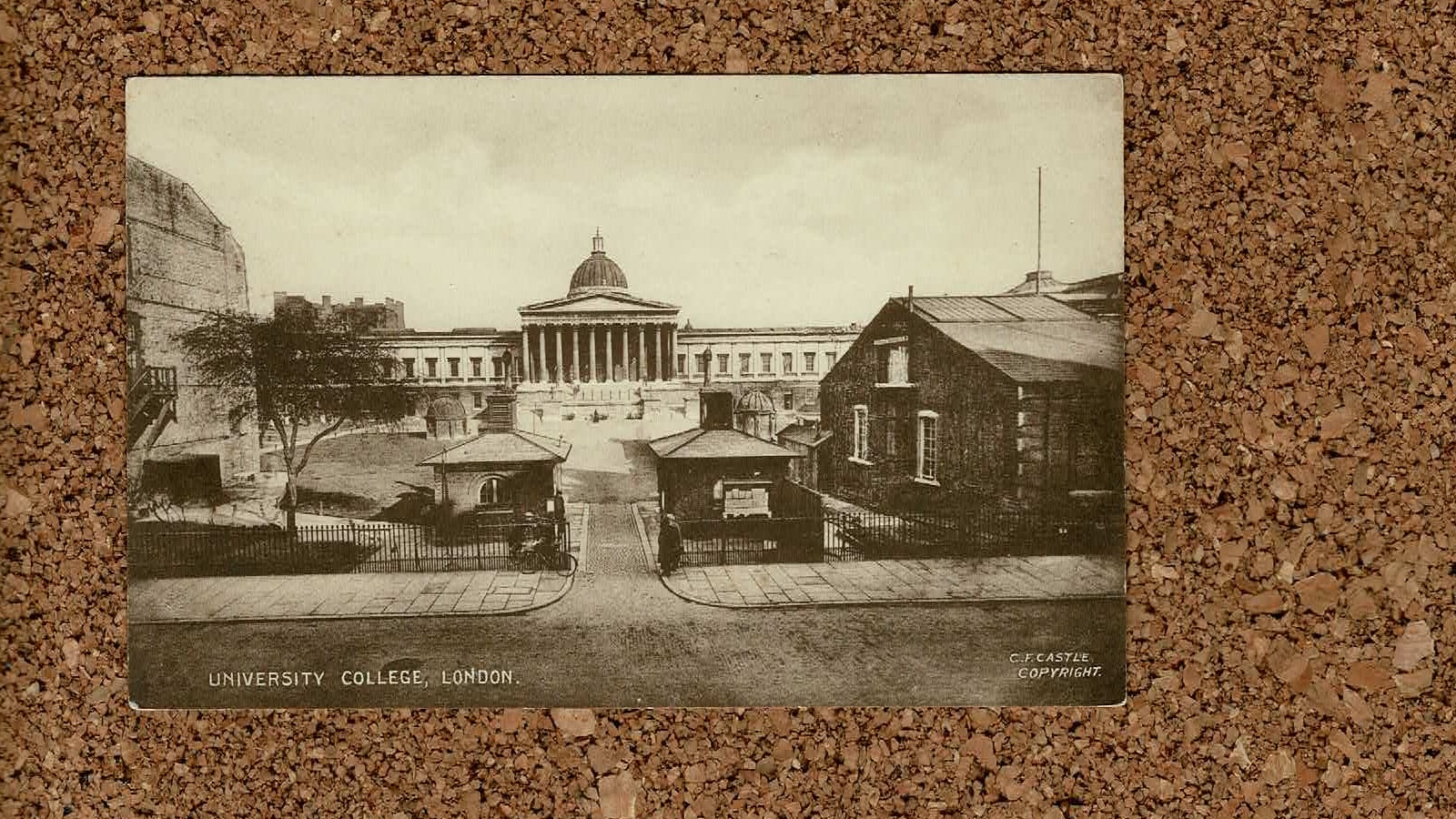

As always, here’s a jigsaw of the postcard. The card hasn’t been posted, so I can’t date it for sure, but I would guess its from the first decade of the twentieth century.

It’s not only UCL which is 200 today – this is also the two hundredth higher education postcard blog on Wonkhe. I’m very grateful to the very fine folk at Wonkhe for enabling me to share these postcards and stories with you. And I’m even more grateful to you for reading and commenting. There’s stacks more postcards and universities I haven’t done yet, so I’ll be here for a while yet, as long as I’m welcome.