- Mary Curnock Cook CBE chairs the Emerge/Jisc HE Edtech Advisory Board, and Bess Brennan is Chief of University Partnerships with Cadmus. Cadmus is running a series of collaborative roundtables with UK university leaders about the challenges and opportunities of generative AI in higher education.

- Yesterday, Wednesday 26th February, HEPI and Kortext published the Student Generative AI Survey 2025: you can read that here.

Clarity and consistency – that’s what students want. Amid all the noise around Generative AI and assessment integrity, students are hugely concerned about the risk of inadvertent academic misconduct due to misunderstandings within their institutions around student use of GenAI.

That was the message coming loud and clear from the HE leaders at Cadmus’ latest invite-only roundtable, which included contributions from LSE, King’s College London, University of Exeter, Maynooth University and the QAA.

As Eve Alcock, Director of Public Affairs at QAA, put it:

‘Where there’s lack of clarity and uncertainty, student anxiety goes up enormously because they want to do what’s right. They want to engage in their assessments and their learning honestly. And, without clarity, they can’t be sure that they are doing that.‘

Leaders shared examples of good practice around how universities are working in partnership with students to understand how they are using GenAI, as well as their concerns and what faculty and leadership need to know to encourage greater clarity and consistency.

LSE: Student use of AI

At LSE, student use of GenAI has been the focus of a major research project, GENIAL. It’s a cross-departmental initiative to explore the students’ perceptions and experiences of GenAI in their own learning process.

According to Professor Emma McCoy, Vice President and Pro-Vice Chancellor (Education), AI is being used widely by LSE students on the courses covered by the project, and they are specifically using it to enhance their learning.

However, there were risks when AI was brought into modules as part of the project: when it was introduced too early, some students lacked the foundational skills to use it effectively. Those who relied on it heavily in the formative stages generally didn’t do so well in the summative. Using AI tools sped up coding for debugging in data science courses, for example, but there were also examples of AI getting it wrong early on and students taking a wild goose chase because they lacked the foundational skills to recognise the initial errors. In addition, despite banning uploads, students uploaded a variety of copyrighted materials.

While LSE has comprehensive policies around when and how students can use GenAI tools and how it should be acknowledged, only a predicted 40% acknowledged AI use in formative assessments in the project. In any case, such policies may become quickly redundant in any university, warned Professor McCoy:

‘We’re already seeing AI tools being embedded across most platforms so it’s going to be almost impossible for people to distinguish whether they’ve actually used AI themselves or not.‘

Maynooth University: Co-creating for clarity

For Maynooth University in Ireland, the starting point has been the principle that AI is for “everyone but not everything”. Leaders were aware that students were feeling nervous and uncertain about what they could use legitimately, with contradictory guidance sometimes being given about the use of tools with embedded AI functionality, such as Grammarly.

Students were also concerned about a perceived lack of transparency around the use of AI. They felt they were being asked to put great effort into demonstrating that they were not using AI in their work but their openness wasn’t necessarily being reciprocated by the academic staff.

Maynooth’s answer was to set up an expert and genuinely cross-disciplinary AI advisory group to work on complementary student and staff guidelines. Crucially, they brought on board a large group of students to work on the project. From undergraduates through to PhD students and across faculties, students worked in sprint relays on the guidelines, building the “confidence to be able to contribute to this work alongside their academic colleagues to try and remove some of the hierarchies that were sometimes in place,” said Professor Tim Thompson, Vice-President (Students and Learning).

One result was greater clarity around when GenAI use is permitted, with a co-created policy setting out parameters from no GenAI permitted through to mandated GenAI use and referencing.

University of Exeter: Incubating innovation

At the University of Exeter, new guidelines similarly describe every assessment as either AI integrated, where GenAI is a significant part of the assessment, AI supported, where ethical use of GenAI is accepted along with appropriate transparency, or AI prohibited. Alongside clear calls for students to be open about their GenAI use is a push for staff to also show best practice and be transparent with students if they are using GenAI to monitor or assess their work.

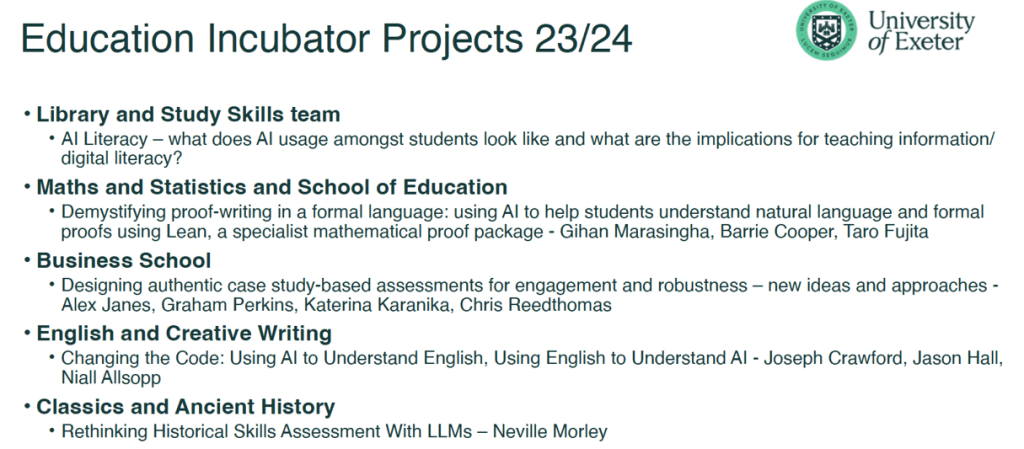

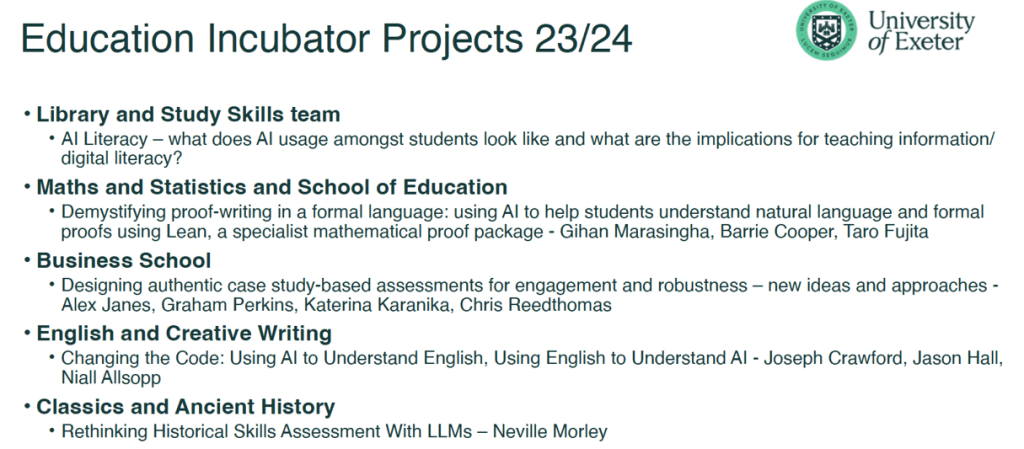

To that end, Exeter is supporting staff to pick up the challenge of integrating GenAI into learning and teaching to better understand the ways in which students are accessing these tools. Exeter’s Education Incubator offers opportunities for staff to explore pedagogic innovation in partnership with students, with the intention of scaling up successful interventions. Projects include rethinking historical skills assessment with LLMs in Classics and Ancient History and student-led hackathons on detecting bias in AIs.

While recognising the opportunities offered by AI for democratising access to learning, with innovations such as 24/7 coaching, Professor Tim Quine, Vice-President and Deputy Vice-Chancellor Education and Student Experience, also highlighted the danger of ever-widening digital divides:

‘There is a significant risk that AI will open up gaps in access to support where privileged students can access premium products that are inaccessible to others, while universities are struggling to navigate the legal, ethical and IP issues associated with institutional AI-supportive technologies, even if we’ve got the budgets to put those technologies in place.‘

King’s College London: rethinking assessment

‘No one wants more assessment!‘ declared Professor Samantha Smidt, Academic Director, King’s College London.

‘Talking to staff and to students about assessment, they’re asking for things to be different, to be more meaningful and rewarding, but nobody’s saying we don’t have enough of it.’

King’s has grasped the opportunity to rethink assessment in a holistic way as a result of, but not limited to, the AI imperative. Aware that students are keen for credit-focused work to be transparently comparable across modules, and for marks to be comparable across markers, King’s has been working on culture change, socialising ideas around a new approach to assessment.

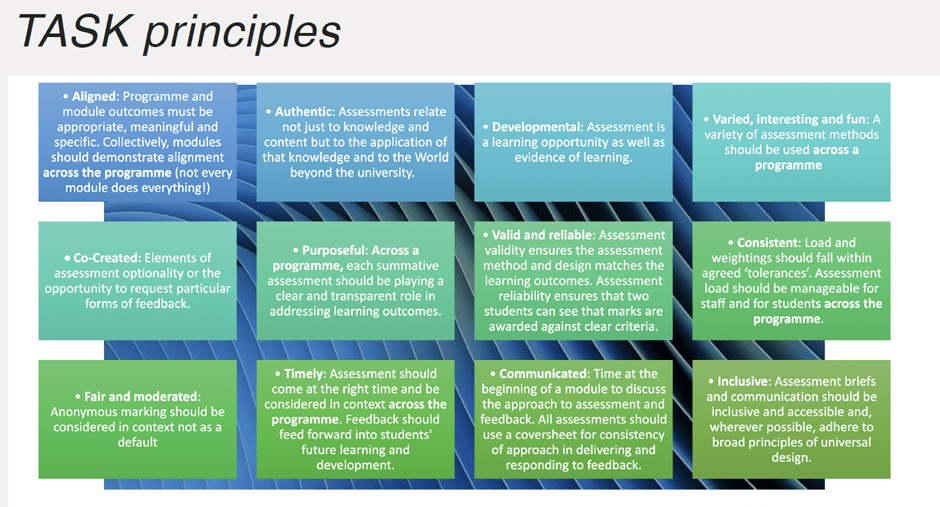

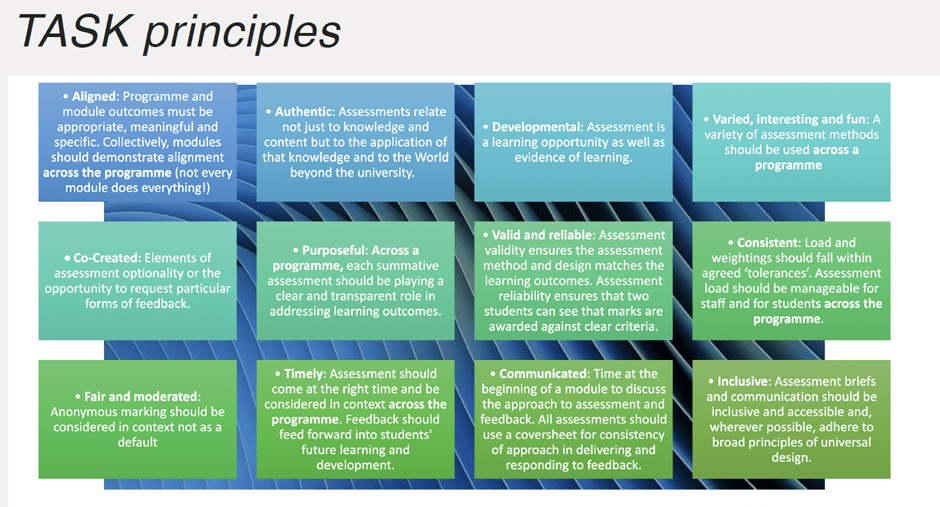

Professional development opportunities – and, importantly, funding, for staff to explore areas of interest within a new assessment framework, TASK – have been allied with student partnership work. Pilots are trialling programmatic assessment across 10 programmes, focusing on assessment timings, tariffs, a shift to more formative assessment and a drive to reduce turnaround times.

In the loop

AI policy in HE is an increasingly complex area, with staff AI literacy requiring as much attention as student use of GenAI tools. In such a fast-developing field, where AI is going to become ever more woven into the fabric of the everyday technology used in academic work, engaging staff and students with emerging issues is critical.

‘The thing we hear time and time again is to keep partnering with and learning from students as a continuous process,‘ urged QAA’s Eve Alcock:

Some AI policies will have been in place for a year, two years now, which is brilliant, but are they still working? Is there a need to evolve them? Making sure that students are fully within that loop is incredibly important.