- Joseph Morrison-Howe is an undergraduate Economics student at the University of Nottingham. He completed an internship with HEPI during the summer of 2024. In this weekend long read, he discusses the history of marketisation in higher education and considers whether applicants have enough information to make informed judgements about where and what they study.

Executive summary

Study at university can be hugely beneficial for students intellectually, socially and financially. However, degrees that lead to low earnings can make individuals who study in higher education financially worse off and can impose an external cost on the taxpayer. This HEPI Policy Note uses the economic framework of market failure to argue it is likely that too many students are studying degrees that result in low earnings. Applicants should be free to choose a course according to their preferences but, they need to be encouraged to use salary outcome data to help them make an informed decision about what degree to study.

Key findings:

- Existing data suggest that one in five graduates would have been financially better off not entering higher education at all. Some 40% of undergraduate students might have chosen a different route, although only 6% would not have entered higher education.

- This report argues that reforms announced in 2022 to the repayment terms of student loans, from the old Plan 2 to the new Plan 5 system, will likely make university financially worthwhile for fewer students.

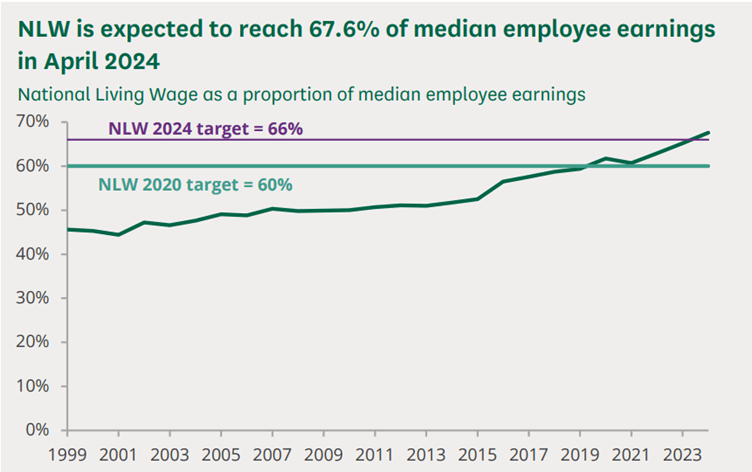

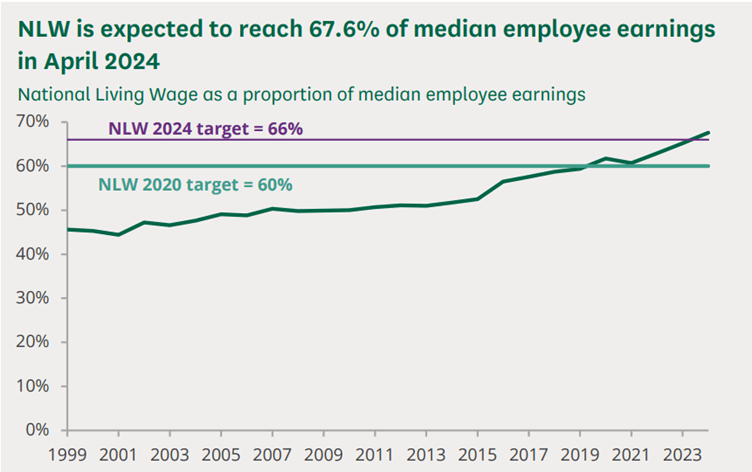

- The graduate premium, the difference between the earnings of graduates and non-graduates, is also likely to decrease as the National Living Wage increases the wages of non-graduates.

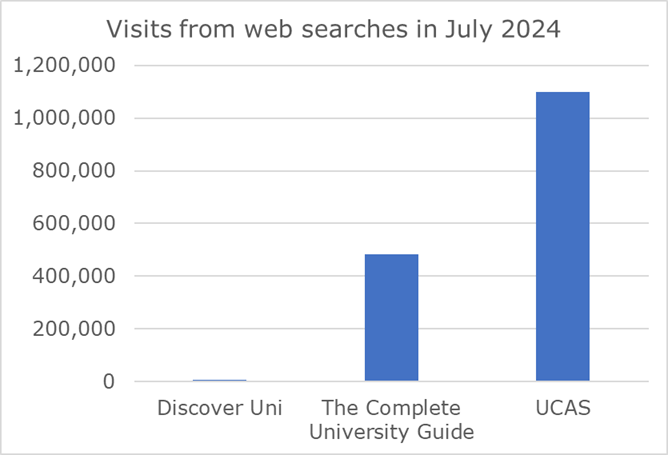

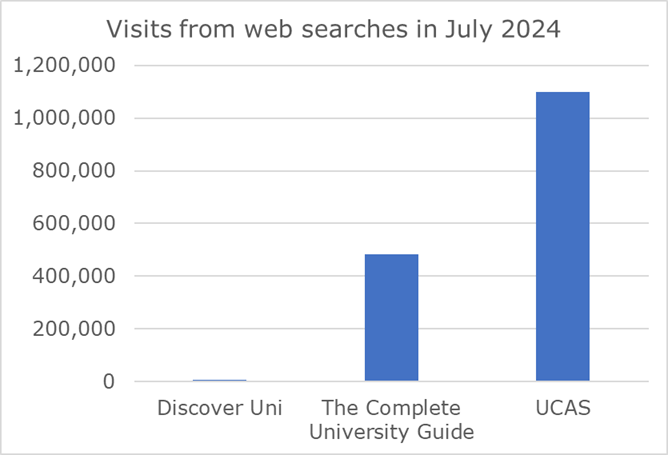

- This report proposes imperfect information as a possible cause of market failure. Prospective students should make best use of information about graduate earnings when choosing what, where or whether to study at university. The official website for information about higher education, Discover Uni, had less than 7,000 website visits in July of 2024. In the same month, nearly half a million visited the website of the Complete University Guide, an online university league table.

Policy recommendations:

- Discover Uni data about graduate earnings should be displayed on UCAS so that more students use this information when making decisions about university studies.

- Satisfied average graduate earnings for each course should be displayed alongside the annual salary for National Living Wage work and the average graduate and non-graduate salaries. This should help students judge if studying individual courses would be financially worthwhile.

- Careers advisors should support applicants to be fully informed about the benefits of higher education – including that not everyone is financially better off for attending university.

Market analysis and higher education

Prior to the 1830s, one would be hard-pressed to convincingly describe higher education in England as a competitive market – a place where many buyers choose to buy goods or services from many sellers, who compete to win the choice of these buyers. The Universities of Oxford and Cambridge maintained a duopoly (a market dominated by two sellers) for nearly 500 years.[i] Since the early nineteenth century, changes in government policy, alongside growth in the number of universities and students, have meant higher education in England has taken on more of the characteristics of a market.

The barriers to becoming a university in England have decreased over time and choice for students has broadened. Prior to the Coalition Government of 2010, the following changes happened to the higher education sector which incidentally laid the foundation for marketisation:

- Growth in the number of universities, which provided more choice for students;

- growth in student numbers; and

- the formation of UCAS (originally UCCA, the Universities Central Council on Admissions), providing a ‘single nationwide application process’, creating a sector that resembled a marketplace.[ii]

It was the introduction and gradual increase of tuition fees paid by the student as opposed to funding via grants from the Government that really introduced market incentives to higher education in England.

By the 1990s, with growing demand from students, the government’s ability and willingness to fund the higher education sector came into question; between 1976 and 1996, government funding per student fell by 40%, according to the Dearing Report.[iii] As a result, the greater burden for funding higher education fell on students. Tony Blair’s government introduced ‘top-up’ fees of £1,000 paid upfront by students in 1998 to supplement government funding. In 2004, the fees rose to £3,000, covered by an income-contingent loan.

The Coalition Government’s rise in tuition fees to £9,000 caused the most significant change in the structure of the higher education sector in England. This is because, as David Willetts (then University Minister) wrote, the new higher fees largely

replaced funding via a Government agency providing grants to universities with funding via the fees (funded by loans) which students brought with them.[iv]

Consequently, to attract funding for teaching, universities had to compete to attract students, as the funding came directly from students. The Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS) wanted ‘to ensure that the new student finance regime supports student choice, and that in turn student choice drives competition’.[v] The characteristics of choice and competition that BIS wanted to introduce are the key characteristics of a market.

The new funding model increased competition between universities for students, first because they received funding for each student they taught and secondly, because these policy changes allowed for the removal of student number caps, which had thus far artificially limited the number of places institutions could provide. More places were made available and students were given more meaningful choice about where to study.

The increasing number of universities and the introduction of UCCA were not policies intended to create a market, but there is evidence from the coalition government of purposeful marketisation. The 2011 white paper ‘Students at the Heart of the System’ from BIS showed their clear intention to introduce what they referred to as ‘a more market-based approach’ to higher education with the new funding system.[vi] The Coalition Government’s support for the new funding system was not just as a solution to the instability and underfunding of the grant-based system but because of the market incentives a fee-based funding model would introduce.

Not all aspects of the current higher education sector in England operate like a typical market. Entry requirements mean that students’ ability to choose between universities is contingent on the grades they achieve (but the growth in the number of universities means that for a given set of grades, a student can choose between many universities). Also, students only bear the cost of their studies if they can afford to do so, as student loan repayments are only made above a particular level of earnings. In typical markets, consumers bear the cost upfront. Though important for making university studies accessible, we will see, the fact that payment is not made upfront makes the sector vulnerable to market failure.

Despite these qualities, it is clear the sector has been marketised:

- students now have more choice, and

- universities now engage in more competition.

There are lots of reasonable critiques of marketisation. Nevertheless, since marketisation has taken place, it can be useful to apply economic analysis to higher education. This report considers the higher education sector as a market and consequently uses economic analysis to assess if the higher education sector works efficiently for both students and wider society. The purpose of this economic analysis is to identify how to improve the higher education sector so it works best for students and wider society.

Markets and market failure in higher education

Marketisation policies introduce characteristics of a market in the hopes that the outcomes of a market will materialise. The prized outcome of markets is efficiency. An efficient market is one where the resources are allocated to give the best outcomes for society; choice allows the allocation of students to the university that best suits them, and competition incentivises the allocation of university funds where they will most improve the institution. If a market is efficient, the allocation of resources cannot be changed to make someone better off without making someone else worse off.

The outcome of markets is not always efficient; markets are prone to fail.

Market failure occurs when resources are not allocated efficiently, to give the best outcomes for the consumer and wider society.

A market failure usually results in:

- too much of a good being provided;

- too little of a good being provided; or sometimes,

- none of a certain good being provided at all.

One example of market failure might be the market for antibiotics. If antibiotics are cheap to buy, people might purchase them even if they are not sure they need them. Over time, the overuse of antibiotics can lead to the development of antibiotic resistance, where antibiotics no longer work for the people who really need them. This is a case where market failure has led to a good being provided in excess and a more efficient outcome would see less of it provided.

This report focuses on the higher education market failing and allocating too many students to degrees that result in low earnings. In this section, I discuss how students studying degrees that lead to low earnings can result in market failure, under certain conditions. In the next section, I will analyse a possible cause of this market failure.

Market failure: degrees that lead to low earnings

For the majority of graduates, studying at university gives them — and the wider economy — good financial returns. However, the market fails and allocates too many students to courses that will lead to low graduate earnings (‘low-earning degrees’). This makes individual graduates financially worse off, compared to if they had not gone to university, and imposes an external cost on the taxpayer.11 In this case the choice of degree (or to study at all) has led to suboptimal outcomes for the individual (the student) and wider society and is therefore a case of market failure.

There is evidence to suggest many students believe they would have been individually better off making a different choice of degree, institution or even entire pathway (such as doing an apprenticeship instead). In the 2024 HEPI / Advance HE Student Academic Experience Survey, four in ten students said they would have been better with a different choice (though only 6% would not have entered higher education).[vii] This suggests these students think there was a more efficient way of allocating (their own) resources even before they know what their lifetime earnings will be.

Not all degrees that result in low earnings are necessarily cases of market failure. There is only a market failure present if there could have been a better allocation of resources, that is, students could have made a different choice that bettered themselves or wider society.

It is likely many students do not just think about earnings when they consider the value of their degree. If the individual valued their Philosophy degree for other reasons – they enjoyed the content, valued the overall university experience, and so on – it may still have been worth it for them even if it did not increase their earnings. In this case, a degree like Philosophy may have been the best option for society if these benefits to the individual student outweigh the lower earnings (and another other costs to both the student and wider society). If so, the allocation would still be efficient and this would not be a case of market failure.

Another situation where a low-earning degree may not be a case of market failure is when the degree has such large social (as opposed to individual) benefits that the choice of any other alternative would lead to a worse outcome for society. For example, if a student studies to be a social worker and this leads to low earnings, the benefits to society that stem from the social work degree will be large enough that any other choice on the student’s behalf would have made society worse off.

The examples of Philosophy and Social Work degrees are not cases of market failure because of the benefits they offer to either the individual or the rest of society. These benefits are not easily quantifiable, so it is difficult to determine which low-earning degrees are examples of market failure and which are not. Below, I will argue that if students are given clear information about the earnings from different degrees, they will be more capable of making that judgement themselves.

The effect of too many students studying low-earning degrees (before reforms to loan repayment terms)

For individual students, there is a financial consequence of choosing to study a degree that will likely result in low earnings. A 2020 report by the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) looked into the impact of undergraduate study on lifetime earnings. The report estimated that ‘one in five undergraduates would have been better off financially had they not gone to university.’[viii]

The IFS compared the lifetime earnings of a cohort of graduates to a counterfactual group that did not attend university, accounting for the difference in income tax, National Insurance and student loan repayments the graduates will have paid over their working life compared to the non-graduates. They then calculated the net lifetime returns for graduates, defined as ‘the lifetime gain or loss in earnings as a result of attending higher education for the individual, after taking into account the effect of the tax and student loans system.’[ix] The IFS found that a fifth of graduates earn less over their lifetimes than if they had not entered higher education.

Not all of the 20% of graduates that would have been better off had they not entered higher education will be cases of market failure. Some may be a Philosophy student that places a high personal value on the knowledge they gained, some may be social workers that provide great value for society, others may have studied a high earning degree and not utilised it. Furthermore, changing the discount rate the IFS use changes the proportion of students that finically benefited from higher education, as David Willetts points out. [x] Though, the IFS results are clear that not everyone entering higher education benefits from it financially.

When students choose to study a low-earning degree, there is also an external cost to the taxpayer. This external cost (a cost to a third party not involved in the transaction) arises because the taxpayer must cover the proportion of a student loan which a graduate has not paid back by the time their loan is written off. Prior to the implementation of reforms in the repayment terms of student loans announced in 2022, only 27% of graduates were estimated to repay their student loan in full.[xi]

The resource allocating and budgeting (RAB) charge is used to estimate the ‘cost to Government of borrowing to support the student finance system’. London Economics, an economics consultancy, estimated that the RAB charge for the 2022/23 cohort of students (who began their studies before the implementation of the 2022 reforms) was 10.2%. That is, the government was expected to cover 10.2% of the total value of the student loans taken out that year.[xii]

These costs, imposed on the student and wider society, might be avoided if students chose different degrees. Future earnings can be altered by a student’s choice of course to study and choice of institution to study at:

Even when comparing students with similar prior attainment and family background, different degrees appear to have a significantly different impact on early career earnings. Studying medicine or economics increases earnings five years after graduation by 25 per cent more than studying English or history. Attending a Russell Group university increases earnings by about 10 per cent more than the average degree.[xiii]

If students who chose to study low-earning degrees had instead chosen to study higher-earning degrees, they would have been less likely to impose an external cost on the taxpayer. Though, as I will explain, reforms to the student loan system mean the external cost to the taxpayer is now very small. Importantly, those students would also be more likely to give themselves positive net lifetime returns to their studies. These outcomes could make society better off. The current allocation of too many students to degrees that result in low earnings is an inefficient one. In the sense defined above, the higher education market is failing.

The impact of the reforms to the repayment terms of student loans (the move from Plan 2 to Plan 5)

The reforms announced in 2022 to the ‘Plan 2’ repayment terms on student loans have shifted the financial burden of low-earning degrees from the taxpayer to the graduate.

Under the new Plan 5 system, the income threshold at which graduates begin to make loan repayments was lowered from £27,295 to £25,000, the repayment period (after which loans are written off) was lengthened from 30 years to 40 years and the interest rate on student loans was reduced from RPI+3% down to just RPI (a measure of inflation).[xiv] These reforms have an uneven effect on graduates across the income distribution.[xv] The reduction in the repayment threshold will mean that lower-earning graduates will pay back more of their debt, and some will begin to pay it back for the first time. The lengthening of the repayment period will mean that low-earning graduates will pay back their loan for longer. The lowering of the interest rate will mean that high-earning graduates (who always would have paid back their loan in full) will now make smaller interest payments.

London Economics estimates that the RAB charge under the new terms of repayment will fall to 4.1% from 10.2%. This means that the reforms have transferred the costs of low-earning degrees from the government, which will now have to write off less debt, to the graduate, who must pay back more of it. As low-earning graduates will now make larger student loan repayments, attending university will not be financially worthwhile for more of them.

A fair assumption is that, since costs are only incurred in the future, prospective students will not be very responsive to these reforms by choosing low-earning degrees in lower numbers. Even after maximum fees were raised from around £3,000 to £9,000 in 2012, there was no significant long-term decrease in the number of applicants.[xvii] If this is the case, a greater proportion of students will now have negative net lifetime returns from their studies. Therefore, for this reform to have a positive outcome on low-earning graduates, these impacts would have to be available and clearly explained to prospective students.

The graduate premium and positive financial returns

The graduate premium is the increase in salary attributed to achieving a degree. To receive positive financial returns from studying, one’s graduate premium must be larger than their loan repayments and increased income tax and National Insurance payments. There is evidence to suggest that the graduate premium has fallen as the higher education sector has grown. Due to increases in the minimum wage, I believe the graduate premium is likely to fall further. This is likely to put a strain on the amount of students experiencing positive financial returns.

As the number of graduates increased throughout the 20th and into the 21st century, it was thought that the graduate premium would decrease. This is, in part, because as the supply of graduates increased their scarcity reduced meaning the premium an employer would pay to hire a graduate over a non-graduate should have fallen. A 2021 study by the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) and a team at the University of Warwick found early evidence of a 7-percentage point decline in the graduate premium.[xviii]

Recent increases in the National Living Wage are likely to further reduce the graduate premium by increasing the average wage of non-graduates. To make the UK a high-wage economy, the Government has been using National Minimum Wage legislation to increase the pay of the lowest paid. In 2020, the Conservative Government asked the Low Pay Commission to ensure the National Living Wage was two-thirds of median earnings by 2024, a target which has now been met.19 Assuming non-graduates are more likely than graduates to earn the National Living Wage. As National Living Wage has increased in relation to median pay, the average wage of non-graduates will have likely increased more than that of graduates. The graduate premium is likely to have further declined. As a result, for more students, it will not have been financially worthwhile to attend university.

Conclusion

In this section, I argue that there is a market failure and too many students are choosing to study degrees that result in low earnings. The reforms to the repayment terms of student loans and a possible decline in the graduate premium are likely to increase the proportion of graduates who are financially worse off for having gone to university. The next section of this Policy Note attempts to explain why this market failure of too many students choosing to study low-earning degrees is taking place.

The causes of market failure in higher education

This section will look at imperfect information as a possible cause of the market failure. There are other possible causes, such as low teaching quality or the fact that an individual student’s decision about whether and where to study also has effects on wider society. The government’s provision of information about graduate salaries is thought to have solved the problem of imperfect information. But this Policy Note focuses on imperfect information because prospective students are not seeing the information about graduate salaries.

Imperfect information occurs when all the parties in a transaction do not have full information about the transaction. If applicants do not know about the career prospects of a low earning degree, they may choose to study it thinking it will enhance their career prospects and then struggle to find a well-paying job after graduation. This could cause an inefficient allocation of students to courses.

People familiar with the higher education sector could likely name the universities that frequently top league tables and which subjects generally lead to high earnings. They may therefore may believe that applicants have roughly enough information to choose the best course for them. This knowledge is not common for all applicants, particularly for applicants who will be the first in their family to attend university (now roughly two-thirds of current undergraduates).[xx] An A-level student who I tutor recently demonstrated that some applicants do not have perfect information about university courses. I asked him out of the universities he wanted to apply to, which he would most like to attend. He wanted to study Management. He said he would like to go to university x “because they have a brand-new building for the business school.” I then showed him that average earnings for Management graduates 5 years after completing university x’s course were over £20,000 less than those of another university he planned to apply to. After this conversation, he chose not to apply to university x. Not all applicants have sufficient knowledge about university courses and this can cause them not to choose the course that would have been best for them.

While introducing marketising reforms since 2010, successive governments have been keen to ensure that applicants do not have imperfect information. A 2016 white paper stated an ambition for ‘more competition and informed choice into higher education’.[xxi]

As a result, prospective students now arguably have access to enough information to make informed choices. The official website for information about higher education, Discover Uni (formally Unistats) provides a wealth of information to prospective students. Discover Uni has information on student satisfaction, the entry grades of past students and information about career prospects for each course at a given university. Data from the Graduate Outcomes Survey and the Longitudinal Educational Outcomes data set are used to provide prospective students with information about the employment rate of past graduates and their earnings 15 months, three years and five years after completing a course. The wealth of information available to prospective students suggests that imperfect information cannot be the reason for too many students choosing courses that will lead to them earning less over a lifetime than if they had not studied at all.

Although prospective students have access to information about employment prospects on the Discover Uni website, few choose to use it. In July 2024, only 6,600 people visited the website.22 In the same month, 481,800 people visited the website of The Complete University Guide, an online university league table, suggesting rankings like these are used more often to make decisions about what and where to study. In the same month, 1,100,000 people visited the UCAS website (the main way to apply for higher education in the UK), which gives an indication of just how many see the information about courses and institutions it provides.

The problem may not be imperfect information, but imperfect knowledge. That is, it is not the lack of availability of information that means too many students study degrees that are not financially worthwhile but instead that applicants are not seeing the information about employment prospects.

Ensuring students see information about graduate salaries will help to correct the market failure of too many students choosing to study low-earning degrees, but it may not fully address information problems. This is because, graduate outcomes data is not a perfect indicator of what a given prospective student will earn. Past data on graduate outcomes cannot tell a prospective student about future labour market changes. However, compared to using no data at all, graduate outcomes give prospective students a good indicator of what they are likely to earn.

Graduate outcomes data may not be currently used because students (and teachers) might not fully understand the implications of the new Plan 5 repayment system. Students may have less incentive to find out the financial returns of a degree if they think a negative return would be covered by the government ‘safety net’. It may therefore be more important than ever to explain that since the 2022 reforms, most students will pay back all or almost all of their loans themselves.

The next section of this report shall propose recommendations to improve the use of the data on Discover Uni.

Policy response

Some students are choosing to study degrees that will likely lead to them having low earnings. When applying to university, students are not using the information about graduate salaries for specific courses, provided on the Discover Uni website. Without the proper use of information about how financially worthwhile degrees are, a fifth of students choose degrees that result in them earning less over their lifetime than if they had not studied at undergraduate level.9

The choice of what and where to study is an individual one; it may depend on what dream job one had as a child, the fact one may have to stay close to home to care for a relative or because one wants to improve their lifetime earnings. Regardless of why one chooses to study a given course, as it is now the student who is most likely to pay for their studies, they should be free to choose what and where to study. However, students should be exposed to the reality that their choice of course may result in them earning less over a lifetime than if they had not studied at university. Students should be encouraged to use information about graduate outcomes and this information should be explained to them. Careers advisors should explain that not all degrees are financially worthwhile and help applicants navigate the available information on graduate salaries.

To prevent students from unknowingly choosing courses that will likely lead to them earning low salaries, information about graduate outcomes should be made more usable. Therefore, the main recommendation from this HEPI Policy Note is that all of the data on Discover Uni (the government website for data which students rarely use) should be integrated into the UCAS pages for individual courses. This includes the salary outcomes for each course, or the lowest level of granularity Discover Uni provides. This makes it more likely that students applying for a course via UCAS will use this information to better inform their decisions.

Discover Uni graduate earnings data should be stratified before it is integrated into UCAS information pages. This involves weighting graduate earnings by social background, reflecting the proportion each social group represents in the wider population. Stratification would ensure that high earnings statistics from a given course do not simply reflect a cohort dominated by already affluent students.

Alongside the average graduate salaries for specific courses, the average graduate and non-graduate salaries should be displayed. Prospective students could be shown the current salary for a full-time minimum wage worker of £23,795 to help them judge if going to university would be financially worthwhile.[xxiii]

[i] William Whyte, The Medieval University Monopoly, History Today, March 2018 https://www.historytoday.com/miscellanies/medieval-university-monopoly

[ii] David Willetts, A University Education, 2015,p40-44

[iii] The Dearing Report, Higher Education in the learning society, 1997, p267

[iv] David Willetts, A University Education, 2015, p. 274

[v] Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, Students at the Heart of the System, June 2011, p.19 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/31384/11- 944-higher-education-students-at-heart-of-system.pdf

[vi] Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, Students at the Heart of the System, June 2011, p.73 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/ government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/31384/11- 944-higher-education-students-at-heart-of-system.pdf

[vii] Calculation from: Jonathan Neves, Josh Freeman, Rose Stephenson & Dr Peny Sotiropoulou, Student Academic Experience Survey 2024, June 2024, p.27https://www.hepi.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/SAES-2024.pdf

[viii] Jack Britton, Lorraine Dearden, Laura van der Erve and Ben Waltmann, The impact of undergraduate degrees on lifetime earnings, Institute of Fiscal Studies, February 2020, p.8 https://ifs.org.uk/sites/default/files/output_url_files/R167-The-impact-of-undergraduate-degrees-on-lifetime-earnings.pdf

[ix] Jack Britton, Lorraine Dearden, Laura van der Erve and Ben Waltmann, The impact of undergraduate degrees on lifetime earnings, Institute of Fiscal Studies, February 2020, p.22 https://ifs.org.uk/sites/default/files/output_url_files/R167-The-impact-of-undergraduate-degrees-on-lifetime-earnings.pdf

[x] David Willets, Are universities still worth it?, The Policy Institute King’s College London, January 2025, p.24 https://www.kcl.ac.uk/policy-institute/assets/are-universities-worth-it.pdf

[xi] Paul Bolton, Student loan statistics, House of Commons Research Briefing, July 2024 https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn01079/

[xii] Dr Gavan Conlon, Maike Halterbeck and James Cannings, Examination of higher education fees and funding in England, London Economics, February 2024, p.55 https://londoneconomics.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/LE-Nuffield-Foundation-HE-fees-and-Funding-in-England-FINAL.pdf

[xiii] Chris Belfield and Laura van der Erve, What determines graduates’ earnings?, The Times, June 2018 https://www.thetimes.com/business-money/economics/article/what-determines-graduates-earnings-w0x6mlwj6

[xiv] Dr Gavan Conlon, Maike Halterbeck and James Cannings, Examination of higher education fees and funding in England, London Economics, February 2024, p.54 https://londoneconomics.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/LE-Nuffield-Foundation-HE-fees-and-Funding-in-England-FINAL.pdf

[xv] Kate Ogden and Ben Waltmann, Student loans in England explained and options for reform, Institute for Fiscal Studies, July 2023 https://ifs.org.uk/articles/student-loans-england-explained-and-options-reform

[xvi] Kate Ogden and Ben Waltmann, Student loans in England explained and options for reform, Institute for Fiscal Studies, July 2023 https://ifs.org.uk/articles/student-loans-england-explained-and-options-reform

[xvii] Mark Corver, UCAS analysis answers five key questions on the impact of the 2012 tuition fees increase in England, UCAS,November 2014 https://www.ucas.com/corporate/news-and-key-documents/news/ucas-analysis-answers-five-key-questions-impact-2012-tuition

[xviii] Gianna Boero, Tej Nathwani, Robin Naylor and Jeremy Smith, Graduate Earnings Premia in the UK: Decline and Fall?, HESA, November 2021, p.1 https://www.hesa.ac.uk/files/Graduate-Earnings-Premia-UK-20211123.pdf

[xix] Brigid Francis-Devine, National Minimum Wage statistics, House of Commons Library, March 2024, p.10 https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-7735/CBP-7735.pdf

[xx] Harriet Coombs, First-in-Family Students, Higher Education Policy Institute, January 2022, p.40 https://www.hepi.ac.uk/?s=Harriet+Coombs

[xxi] Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, Success as a Knowledge Economy: Teaching Excellence, Social Mobility and Student Choice, May 2016, p.8 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a817487ed915d74e33fe4ca/bis-16-265-success-as-a-knowledge-economy-web.pdf

[xxii] Data from aherfs website traffic checker. Data collected in October 2024

[xxiii] Cogent staffing, Understanding the 2024 UK National Minimum Wage increase, February 2024 https://cogentstaffing.co.uk/understanding-the-2024-uk-national-minimum-wage-increase/