On World Food Day we present you with a smorgasbord of stories to consume to show how food and the need to eat connects us all.

Source link

Author: admin

-

Food: The one thing everyone needs

-

Students Weigh In on AI-Assisted Job Searches

Employers say they want students to have experience using artificial intelligence tools, but most students in the Class of 2025 are not using such tools for the job hunt, according to a new survey.

The study, conducted by the National Association of Colleges and Employers, included data from 1,400 recent graduates.

Students who do use AI tools for their job search most commonly apply them to writing cover letters (65 percent), preparing for interviews (64 percent) and tailoring their résumés to specific positions (62 percent). In an Oct. 14 webinar hosted by NACE, students explained the benefits of using AI when searching for career opportunities.

Among student job seekers who don’t employ AI, nearly 30 percent of respondents said they had ethical concerns about using the tools, and 25 percent said they lacked the expertise to apply them to their job search. An additional 16 percent worried about an employer’s reaction to AI-assisted applications, and 15 percent expressed concern about personal data collection.

“If you listen to the media hype, it’s that everybody’s using AI and all of these students who are graduating are flooding the market with applications because of AI, et cetera,” NACE CEO Shawn Van Derziel said during the webinar. “What we’re finding in our data is that’s just not the case.”

About one in five employers use AI in recruiting efforts, according to a separate NACE study.

Students say: Brandon Poplar, a senior at Delaware State University studying finance and prelaw, said during the webinar that he uses AI for internship searches.

“It has been pretty successful for me; I’ve been able to use it to tailor my résumé, which I think is almost the cliché thing to do now,” Poplar said. “Even to respond to emails from employers, it’s allowed me to go through as many applications as I can and find things that fit my niche.”

Through his AI-assisted searches, Poplar learned he’s interested in management consulting roles and then determined how to best align his cover letters to communicate that to an employer.

Morgan Miles, a senior at Spelman College majoring in economics, said she used a large language model to create a résumé that fits an insurance role, despite not having experience in the insurance industry. “I ended up actually getting a full-time offer,” Miles said.

She prefers to use an AI-powered chatbot rather than engage with career center staff because it’s convenient and provides her with a visual checklist of her next steps, she said, whether that’s prepping for interview questions or figuring out what skills she needs to add to application materials.

Panelists at the webinar didn’t think using ChatGPT was “cheating” the system but rather required human creativity and input. “It can be a tool to align with your values and what you’re marketing to the employers and still being yourself,” said Dandrea Oestricher, a recent graduate of the City College of New York.

Maria Wroblewska, a junior at the University of California, Irvine, where she works as a career center intern, said she was shocked by how few students said they use AI. “I use it pretty much every time I search for a job,” to investigate the company, past internship offerings and application deadlines, she said.

Other student trends: NACE leaders also shared results from the organization’s 2025 Student Survey, which included responses from 13,000 students across the U.S.

The job market continues to present challenges for students, with the average senior submitting 30 job applications before landing a role, according to the survey. In recent years that number has skyrocketed, said Josh Kahn, associate director of research and public policy at NACE. “It was about 16 or 17, if I remember correctly, two years ago. That is quite large growth in just two years,” he said during the webinar.

Students who met with an employer representative or attended a job fair were more likely to apply for additional jobs, but they were also more likely to report that the role they were hired in is related to their major program.

Students who used an AI search engine (approximately 15 percent of all respondents) were more likely to apply for jobs—averaging about 60 applications—and less likely to say the job they landed matched their major. “That was a little surprising,” Kahn said. “It does line up anecdotally with what we’re hearing about AI’s impact on the number of applications that employers are receiving.”

Two in five students said they’d heard the term “skills-based hiring” and understood what it meant, while one-third had never heard the term and one-quarter weren’t sure.

Student panelists at the webinar said they experienced skills-based hiring practices during their internship applications, when employers would instruct them to complete a work exercise to demonstrate technical skills.

NACE’s survey respondents completed 1.26 internships on average and received 0.78 job offers. A majority of internships took place in person (79 percent) or in a hybrid format (16 percent). Almost two-thirds of interns were paid (62 percent), which is the highest rate NACE has seen in the past seven years, Kahn said. Seven in 10 students said they did not receive a job offer from their internship employer.

Do you have a career-focused intervention that might help others promote student success? Tell us about it.

-

3 Questions for Professor Mary Wright

Last year, Brown University announced that Mary Wright was embarking on a new adventure in early 2025.

If you are anywhere near or around the CTL world, you likely know (or know about) Mary Wright. Her 2023 JHU Press publication, Centers for Teaching and Learning: The New Landscape in Higher Education, is a must-read for every university leader. Mary—along with Tracie Addy, Bret Eynon and Jaclyn Rivard—also has a forthcoming book with Johns Hopkins (2026), which will provide a 20-plus-year look at continuities and changes in the field of educational development.

Therefore, it was big news earlier this year when Mary moved from her role as associate provost for teaching and learning and executive director of Sheridan Center at Brown to a new position as a professor of education scholarship at the University of Sydney. With Mary now more than six months in her new role, this was a good time to catch up with how things are going.

Q: Tell us about your new role at the University of Sydney. What does a faculty appointment in Australia constitute in terms of teaching, research and administrative responsibilities?

A: As in the U.S., a faculty appointment (here, called an academic appointment) varies greatly across and even within Australian institutions. In my role, I serve as a Horizon Educator, an education-focused academic role, which carries a heuristic of 70 percent time to education, 20 percent to scholarship and 10 percent to leadership or service-related activities. Like my prior 20-plus years of experience in the U.S., I am still an academic developer (called an educational developer in the U.S.), which means that education most frequently involves teaching and mentoring other academics as learners.

I am a level-E academic, which is akin to a full professor role in the U.S. (The trajectory starts at level A, which encompasses associate lecturer and postdoctoral fellows and goes through level B [lecturer], level C [senior lecturer], level D [associate professor] and level E [professor].)

There are many differences between U.S. and Australian higher education, but I’ll highlight two here in relation to those who work in CTLs. The first and most significant is that, in the U.S., educational developers are often positioned as professional staff. In Australia, many universities treat this work with parity to other academics. I feel that this substantially raises the credibility and value of academic development.

Second, professional learning around teaching is a required part of many academics’ contracts, initially or for “confirmation,” and it is structured into their workloads. I first worried that this would prompt a good deal of reactance, but I have not found this to be the case. I now find this to be a more equitable system for students (and academic success), compared to the U.S.’s (primarily) voluntary approach.

Q: Moving from Rhode Island to Australia is a big move. What is it about the University of Sydney that attracted you to the institution, and why did you make this big move at this point in your career?

A: Three factors attracted me to the University of Sydney. First, I was attracted to what I will call their organizational honesty. The institution was very open that they were not where they wanted to be in regard to teaching and the student experience; they wanted to be a different kind of institution. They also had a very clear theory of change, mapping very much onto metaphors I write about elsewhere: requiring convening and community building (hub); support of individual career advancement (incubator); development of evidence-based practice, such as the scholarship of teaching and learning (sieve); and advancing the value of teaching and learning through recognition and reward (temple).

Specifically, USyd was investing in over 200 new Horizon Educator positions, education-focused academics charged to be educational leaders. One part of my role is to work with this amazing group of academics to advance their own careers, as well as to realize the institution’s ambitions for enhanced teaching effectiveness. To anchor this work at a macro level, USyd also had been working very hard on developing and rolling out a new Academic Excellence Framework, which provides a clear pathway to the recognition and reward of education—in addition to other aspects of the academic role

The University of Sydney is also making a significant investment in grants to foster the scholarship of teaching and learning, which has been a long-standing interest of mine but was often done “off the side of the desk.” My role involves working with people, programs and practices to facilitate SoTL.

In addition to university strategy, I was attracted by the opportunity to work with Adam Bridgeman and colleagues in the university’s central teaching and learning unit. Educational Innovation has been engaged in very interesting high-level work around AI and assessment, as well as holistic professional learning to support academics, but like many CTLs, it has been stretched since COVID to advance a growing number of institutional aims. Because of my prior leadership in CTLs, I felt like I could also contribute in this space.

Q: Pivoting from a university leadership staff role to a faculty role is appealing to many of us in the nonfaculty educator world. (Although I know you also had a faculty position at Brown). Can you share any advice for those who might want to follow in your footsteps?

A: For some context, I started my career in the early 2000s in a professional staff role in a CTL and also occasionally adjuncted. I became a research scientist in the CTL, then moved to direct a CTL in 2016 and had an affiliate faculty position (with the staff/administrative role as primary). In 2020, I then moved to a senior administration role (again, my primary role was professional staff). So, I have worn a number of hats.

Three factors have been helpful in transitioning across roles. First, I love to write, and while the scholarly work rarely “counted” for anything in these series of positions, I think it helped me advance to the next step. Second, it’s important to read a lot to stay current with the vast literature on teaching and learning. I think this can add value to my work with individual academics—to help them publish—as well as my work on committees, where there is often some literature to cite on the topic at hand.

Finally, I think professional associations can be very helpful in building bridges and networks, especially for those considering an international transition. In the U.S., the POD Network was a key source of support. Now, before even applying to my current role, I subscribed to the newsletter of HERDSA (Higher Education Research and Development Society of Australasia) and I participated in one of their mentoring programs. I also serve as a co-editor of the International Journal for Academic Development, which exposed me to articles about Australian academic development, and I got some generous and wise advice from Australian and New Zealand IJAD colleagues about the job search.

-

Judge Halts UT’s Comprehensive Ban on Student Speech

SB 2972 was passed after students at several public Texas universities protested the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Jon Shapley/Houston Chronicle via Getty Images

A Texas district court judge on Tuesday ordered the University of Texas system to hold off on enforcing new, sweeping limits on student expression that would prohibit any “expressive activity” protected by the First Amendment between 10 p.m. and 8 a.m.

“The First Amendment does not have a bedtime of 10 p.m.,” wrote U.S. district court judge David Alan Ezra in his order granting the plaintiff’s request for a preliminary injunction. “Giving administrators discretion to decide what is prohibited ‘disruptive’ speech gives the school the ability to weaponize the policy against speech it disagrees with. As an example, the Overnight Expression Ban would, by its terms, prohibit a sunrise Easter service. While the university may not find this disruptive, the story may change if it’s a Muslim or Jewish sunrise ceremony. The songs and prayer of the Muslim and Jewish ceremonies, while entirely harmless, may be considered ‘disruptive’ by some.”

A coalition of student groups—including the student-run Retrograde Newspaper, the Fellowship of Christian University Students at the University of Texas at Dallas and the student music group Strings Attached—sued to challenge the restrictions, which, in addition to prohibiting expression overnight, also sought to ban campus public speakers, the use of drums and amplified noise during the last two weeks of the semester. The restrictive policies align with Texas Senate Bill 2972, called the Campus Protection Act, which requires public universities to adopt restrictions on student speech and expression. The bill took effect on Sept. 1.

“Texas’ law is so overbroad that any public university student chatting in the dorms past 10 p.m. would have been in violation,” said Adam Steinbaugh, a senior attorney at the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, in a press release. “We’re thankful that the court stepped in and halted a speech ban that inevitably would’ve been weaponized to censor speech that administrators disagreed with.”

-

Report Cards, Reshuffles, and Resilience: What Ofsted’s new model could mean for higher education

This blog was kindly authored by Dr. Ismini Vasileiou, Associate Professor at De Montfort University.

The UK Higher Education sector is at a crossroads. With the government’s skills agenda being reshaped, institutions under growing financial pressure, and the first-ever merger between two English universities announced, the landscape is shifting faster than many had anticipated. Into this mix comes Ofsted’s new Report Card for Further Education & Skills (September 2025), which introduces a sharper accountability framework for further education providers.

The report card grades institutions across areas such as Leadership & Governance, Inclusion, Safeguarding, and Contribution to Meeting Skills Needs. At programme level, it assesses Curriculum, Teaching & Training, Achievement, and Participation & Development against a tiered scale ranging from Exceptional to Urgent Improvement.

While this is designed for further education and skills providers, its arrival raises an uncomfortable but necessary question for universities: what if higher education were graded in the same way?

The case for simplicity and transparency

Universities are already subject to layers of oversight through the Office for Students (OfS), the Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF), the National Student Survey (NSS), and graduate outcomes data. Yet, as I noted in the recent Cyber Workforce of the Future white paper, these mechanisms often appear fragmented to policymakers and incomprehensible to the public.

By contrast, the further education report card is direct. A parent, student, or employer can understand at a glance whether a provider is exceptional, strong, or in urgent need of improvement. Were higher education to adopt a similar model, judgments might cover:

- Leadership & Governance: financial resilience, strategic direction, governance quality.

- Inclusion: widening participation, closing attainment gaps, embedding equity strategies.

- Safeguarding/Wellbeing: provision for student welfare, mental health, harassment and misconduct.

- Skills Contribution: alignment with regional economic needs, national priorities in AI and cybersecurity, and graduate employment outcomes.

At the programme level, Achievement and Participation could map onto retention, progression, and graduate success, offering students and employers a clear view of performance.

Risks and rewards for higher education

Of course, importing a schools-style accountability regime into higher education carries risks. Universities are not homogeneous, and reducing their diverse missions to a traffic-light system risks oversimplification. A specialist arts institution and a research-intensive university might both be rated ‘Needs Attention’ on skills contribution, despite playing very different roles in the national ecosystem.

There is also the danger of gaming the system: universities optimising for ratings rather than long-term innovation. And autonomy, long a cornerstone of higher education, would be at stake.

Yet there are potential rewards. Public trust in higher education has been under strain, with questions over value for money and financial viability dominating the narrative. Transparent, comprehensible reporting could rebuild confidence and demonstrate sector-wide commitment to accountability. It could also strengthen alignment with further education at a time when government is explicitly seeking a joined-up skills system.

A shifting policy landscape

The September 2025 government reshuffle underscores why this debate matters. The resignation of Angela Rayner triggered a wide Cabinet reorganisation, with skills responsibilities moving out of the Department for Education and into a new ‘growth’ portfolio under the Department for Work and Pensions, led by Pat McFadden. This shift signals that some elements of skills policy are now seen primarily through an economic and labour market lens.

For Higher Education, this presents both challenges and opportunities. As argued in Bridging the Skills Divide: Higher Education’s Role in Delivering the UK’s Plan for Change, universities must demonstrate that they are not just centres of academic excellence but engines of workforce development, innovation, and regional growth. A report-card style framework could make these contributions more visible, but only if universities are part of its design.

Structural Change: The Kent–Greenwich merger

The announcement that the Universities of Kent and Greenwich will merge in autumn 2026 to form the London and South East University Group is a watershed moment for the sector. It is the first merger of its kind in England, driven by financial pressures from declining international student enrolments, static domestic fees, and mounting operational costs.

The merged entity will serve around 28,000 undergraduates, retain the identities of both institutions, and be led by Greenwich Vice-Chancellor Professor Jane Harrington. Yet concerns remain. The University and College Union (UCU) has warned that ‘this isn’t a merger; it is a takeover’ and called for urgent reassurance on staff jobs and student provision.

In a system with Ofsted-style ratings, such a merger would be scrutinised not just for its financial logic but also for its impact on governance, inclusion, and skills contribution. A transparent rating system might reassure stakeholders that the merged institution is not only viable but also delivering quality and meeting regional needs.

Building on skills agendas

National initiatives like Skills England, the Digital Skills Partnership, and programmes such as CyberLocal demonstrate how higher education can contribute to workforce resilience at scale. The Ofsted report card reinforces this agenda. Its emphasis on contribution to meeting skills needs aligns directly with the notion that higher education must play a central role in the UK’s skills ecosystem, not only through degree provision but through continuous upskilling, regional collaboration, and adaptive curricula.

Shaping the framework before it shapes us

Ofsted’s further education report card is not just an accountability mechanism; it is a signal of where education policy is heading, toward clarity, comparability, and alignment with skills needs.

For higher education, the choice is stark. Resist the model and risk having it imposed in ways that do not fit the sector’s diversity. Or lead the design, shaping a framework that balances accountability with autonomy, and skills with scholarship.

As Universities confront financial pressures, policy reshuffles, and structural change, one thing is clear: the sector cannot afford to sit this debate out. The real question is not whether Higher Education should be graded, but what kind of grading system we would design if given the chance.

-

How can universities best win back public support?

This blog was kindly authored by Professor Annabel Kiernan, Deputy Vice-Chancellor for Education and Student Experience at Goldsmiths University. It follows her speech at a HEPI event with the same title as this blog, held at the 2025 Conservative Party Conference.

To accept this question at its face and to understand what universities can and should do to build back public support, we need to look at how we got here. In broad terms, universities are not the only institutions whose role, purpose and efficacy are being challenged. There has been a wider breakdown of trust between the public and a wide range of local and national infrastructure, both public and private – from water and train companies, to the courts and local government.

In part, this is the inevitable consequence of two periods of significant financial stress – firstly from the 2008 financial crash and its resulting ten-year austerity programme, followed swiftly by the post-COVID cost-of-living crisis. The economic bite for the personal and public purse and the knock-on impact of such economic dislocation has been a considerable shrinking of the wider public realm and a gnawing away at the previous slowly progressive move towards a more ‘bread and roses’ type of social compact for all: of needing the fundamentals of life (bread), but also making available what brings beauty, culture and wellbeing (roses) to wider society, irrespective of economic circumstance. The shrinking of the public realm has pushed back this access to public goods.

Many education institutions, including universities, have attempted to be a buttress for this impact – whether that’s filling in social, behavioural, skills and knowledge gaps from lost learning, responding to increased mental health pressures, trying to mitigate, where possible, the impacts of poverty and other generalised impacts of closures of youth centres, libraries, museums and so on.

Clearly then, universities play a key role in delivering progress to individuals and the broader public. They are core to economic and social growth, delivering these while managing the public’s varied aspirations and differing expectations. The expansion of higher education was sought to widen the benefits of a university education and experience. Even before the Blair expansion in the 2000s, my own family – my mum, the eldest of six, with a miner and a housewife as parents – were beneficiaries, with all six children going to university during the 1970s and 1980s. Despite both leaving school at 14, my grandparents knew that university was the route to a different life. It paid off for all six brothers and sisters, and here I am today, the eldest grandchild of that mobility, a Deputy Vice Chancellor contributing a HEPI blog on public trust in universities.

But, whilst the cost of university entry has now significantly increased, the mobility pay off, or graduate premium, appears more challenged. This is despite the OECD’s Education at a Glance 2025 report showing that, over the course of a lifetime, attending university still delivers financially. In times of heightened economic stress, however, the public needs more immediacy in the financial payoff and surety in the belief that infrastructure delivers a high-quality service. We can see the political articulation of the need to see, feel and believe things work and have tangible benefits for individuals, their families and communities now. People’s sacrifices need to matter, and their investment needs to pay off.

So what do universities do to play their part?

As a sector, we work very hard on our civic role, but we need to be more porous. We can’t be seen to effectively privatise public space. We need to be of our places, and lead the charge on building solutions and helping people to navigate change – from how we work with local communities to how we contribute to global challenges. In other words, we need to reemphasise our role in sustaining the social, cultural and intellectual infrastructure of society,

To support that civic role, we need to offer more seamless education journeys and be accessible for learners throughout their lifetime. That means accelerating the ways in which we work in partnership with each other, with colleges, schools, employers and local authorities. Lifelong education is a philosophy, not just a government policy. The Lifelong Learning Entitlement needs to align with a wide range of policies. For example, now that ‘skills’ is situated with the Department for Work and Pensions, what harm in referring people to a bit of modular learning to get their employment on track rather than piecemeal training or benefit sanctions? Universities are a public infrastructure, so we need to connect well with other infrastructure to deliver our part of the ecosystem for individual and collective economic and social gains.

We must remain intentional, be high quality, deliver an excellent experience. There should continue to be robust regulation of bad actors. We should deliver success for all our students and we shouldn’t be a homogeneous model; learners take different pathways through higher learning and need to access it in different ways, through different modes and will have different needs for flexibility. There are specialisms and expertise in research and teaching, and these should remain available as choices. There has been much written about the detrimental impact of out-of-town shopping centres on our high streets. Similarly, if all universities have to deliver at scale for efficiencies, the impact of closures on the towns and cities of smaller, more specialist institutions would be devastating.

At this moment, we need to emphasise our value in relation to the individual economic benefit gained from the investment of a student loan. In other words, highly paid graduate employment. I’m not sure how potent the arguments for the collective economic benefit of universities currently are. Personal storytelling of meaningful impacts, like that of my own family, may have traction in our university locales.

Overall, we need to continue to deliver and continue to engage. We work hard in these spaces already, but we need to tell our story differently and continue to adapt our model.

Importantly, universities have a central part to play in delivering space for reflection, intellectual enquiry, creative and critical action and solutions which will help to navigate us, the public, through these significant and challenging periods of rapid economic, political and technological transition.

As Oppenheim wrote in his 1911 poem:

Hearts starve as well as bodies: Give us Bread, but give us Roses.

What better challenge for universities to continue to rise to.

-

As more question the value of a degree, colleges fight to prove their return on investment

This story was produced by the Associated Press and reprinted with permission.

WASHINGTON – For a generation of young Americans, choosing where to go to college — or whether to go at all — has become a complex calculation of costs and benefits that often revolves around a single question: Is the degree worth its price?

Public confidence in higher education has plummeted in recent years amid high tuition prices, skyrocketing student loans and a dismal job market — plus ideological concerns from conservatives. Now, colleges are scrambling to prove their value to students.

Borrowed from the business world, the term “return on investment” has been plastered on college advertisements across the U.S. A battery of new rankings grade campuses on the financial benefits they deliver. States such as Colorado have started publishing yearly reports on the monetary payoff of college, and Texas now factors it into calculations for how much taxpayer money goes to community colleges.

“Students are becoming more aware of the times when college doesn’t pay off,” said Preston Cooper, who has studied college ROI at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank. “It’s front of mind for universities today in a way that it was not necessarily 15, 20 years ago.”

Related: Interested in more news about colleges and universities? Subscribe to our free biweekly higher education newsletter.

A wide body of research indicates a bachelor’s degree still pays off, at least on average and in the long run. Yet there’s growing recognition that not all degrees lead to a good salary, and even some that seem like a good bet are becoming riskier as graduates face one of the toughest job markets in years.

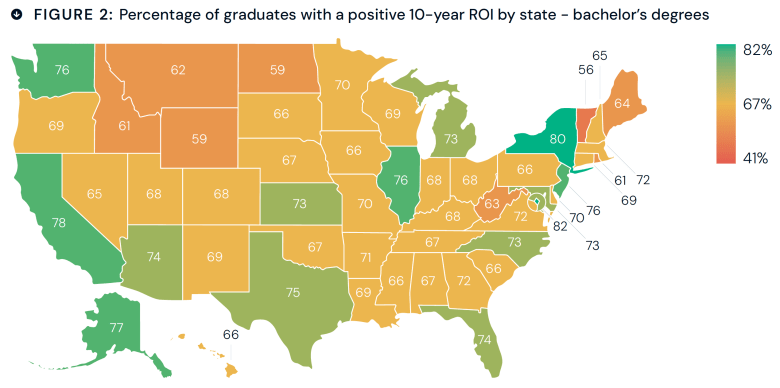

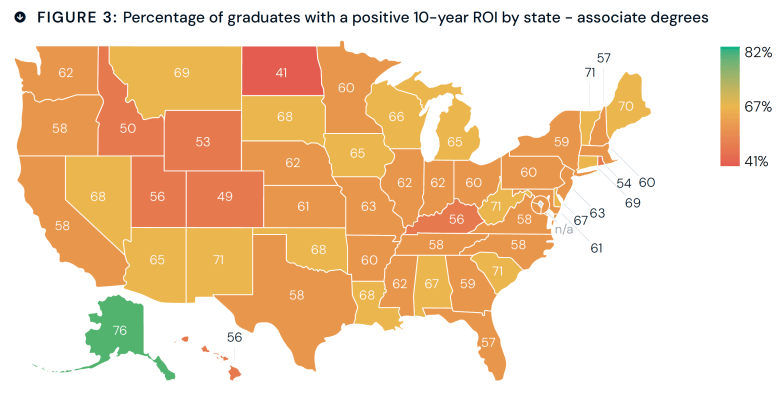

A new analysis released Thursday by the Strada Education Foundation finds 70 percent of recent public university graduates can expect a positive return within 10 years — meaning their earnings over a decade will exceed that of a typical high school graduate by an amount greater than the cost of their degree. Yet it varies by state, from 53 percent in North Dakota to 82 percent in Washington, D.C. States where college is more affordable have fared better, the report says.

It’s a critical issue for families who wonder how college tuition prices could ever pay off, said Emilia Mattucci, a high school counselor at East Allegheny schools, near Pittsburgh. More than two-thirds of her school’s students come from low-income families, and many aren’t willing to take on the level of debt that past generations accepted.

Instead, more are heading to technical schools or the trades and passing on four-year universities, she said.

“A lot of families are just saying they can’t afford it, or they don’t want to go into debt for years and years and years,” she said.

Education Secretary Linda McMahon has been among those questioning the need for a four-year degree. Speaking at the Reagan Institute think tank in September, McMahon praised programs that prepare students for careers right out of high school.

“I’m not saying kids shouldn’t go to college,” she said. “I’m just saying all kids don’t have to go in order to be successful.”

Related: OPINION: College is worth it for most students, but its benefits are not equitable

American higher education has been grappling with both sides of the ROI equation — tuition costs and graduate earnings. It’s becoming even more important as colleges compete for decreasing numbers of college-age students as a result of falling birth rates.

Tuition rates have stayed flat on many campuses in recent years to address affordability concerns, and many private colleges have lowered their sticker prices in an effort to better reflect the cost most students actually pay after factoring in financial aid.

The other part of the equation — making sure graduates land good jobs — is more complicated.

A group of college presidents recently met at Gallup’s Washington headquarters to study public polling on higher education. One of the chief reasons for flagging confidence is a perception that colleges aren’t giving graduates the skills employers need, said Kevin Guskiewicz, president of Michigan State University, one of the leaders at the meeting.

“We’re trying to get out in front of that,” he said.

The issue has been a priority for Guskiewicz since he arrived on campus last year. He gathered a council of Michigan business leaders to identify skills that graduates will need for jobs, from agriculture to banking. The goal is to mold degree programs to the job market’s needs and to get students internships and work experience that can lead to a job.

Related: What’s a college degree worth? States start to demand colleges share the data

Bridging the gap to the job market has been a persistent struggle for U.S. colleges, said Matt Sigelman, president of the Burning Glass Institute, a think tank that studies the workforce. Last year the institute, partnering with Strada researchers, found 52 percent of recent college graduates were in jobs that didn’t require a degree. Even higher-demand fields, such as education and nursing, had large numbers of graduates in that situation.

“No programs are immune, and no schools are immune,” Sigelman said.

The federal government has been trying to fix the problem for decades, going back to President Barack Obama’s administration. A federal rule first established in 2011 aimed to cut federal money to college programs that leave graduates with low earnings, though it primarily targeted for-profit colleges.

A Republican reconciliation bill passed this year takes a wider view, requiring most colleges to hit earnings standards to be eligible for federal funding. The goal is to make sure college graduates end up earning more than those without a degree.

Others see transparency as a key solution.

For decades, students had little way to know whether graduates of specific degree programs were landing good jobs after college. That started to change with the College Scorecard in 2015, a federal website that shares broad earnings outcomes for college programs. More recently, bipartisan legislation in Congress has sought to give the public even more detailed data.

Lawmakers in North Carolina ordered a 2023 study on the financial return for degrees across the state’s public universities. It found that 93 percent produced a positive return, meaning graduates were expected to earn more over their lives than someone without a similar degree.

The data is available to the public, showing, for example, that undergraduate degrees in applied math and business tend to have high returns at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, while graduate degrees in psychology and foreign languages often don’t.

Colleges are belatedly realizing how important that kind of data is to students and their families, said Lee Roberts, chancellor of UNC-Chapel Hill, in an interview.

“In uncertain times, students are even more focused — I would say rightly so — on what their job prospects are going to be,” he added. “So I think colleges and universities really owe students and their families this data.”

The Associated Press’ education coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

The Strada Education Foundation, whose research is mentioned in this story, is one of the many funders of The Hechinger Report.

-

Outcomes data for subcontracted provision

In 2022–23 there were around 260 full time first degree students, registered to a well-known provider and taught via a subcontractual arrangement, that had a continuation rate of just 9.8 per cent: so of those 260 students, just 25 or so actually continued on to their second year.

Whatever you think about franchising opening up higher education to new groups, or allowing established universities the flexibility to react to fast-changing demand or skills needs, none of that actually happens if more than 90 per cent of the registered population doesn’t continue with their course.

It’s because of issues like this that we (and others) have been badgering the Office for Students to produce outcomes data for students taught via subcontractual arrangements (franchises and partnerships) at a level of granularity that shows each individual subcontractual partner.

And finally, after a small pilot last year, we have the data.

Regulating subcontractual relationships

If anything it feels a little late – there are now two overlapping proposals on the table to regulate this end of the higher education marketplace:

- A Department of Education consultation suggests that every delivery partner that has more than 300 higher education students would need to register with the Office for Students (unless it is regulated elsewhere)

- And an Office for Students consultation suggests that every registering partner with more than 100 higher education students taught via subcontractual arrangements will be subject to a new condition of registration (E8)

Both sets of plans address, in their own way, the current reality that the only direct regulatory control available over students studying via these arrangements is via the quality assurance systems within the registering (lead) partners. This is an arrangement left over from previous quality regimes, where the nation spent time and money to assure itself that all providers had robust quality assurance systems that were being routinely followed.

In an age of dashboard-driven regulation, the fact that we have not been able to easily disaggregate the outcomes of subcontractual students has meant that it has not been possible to regulate this corner of the sector – we’ve seen rapid growth of this kind of provision under the Office for Students’ watch and oversight (to be frank) has just not been up to the job.

Data considerations

Incredibly, it wasn’t even the case that the regulator had this data but chose not to publish it. OfS has genuinely had to design this data collection from scratch in order to get reliable information – many institutions expressed concern about the quality of data they might be getting from their academic partners (which should have been a red flag, really).

So what we get is basically an extension of the B3 dashboards where students in the existing “partnership” population are assigned to one of an astonishing 681 partner providers alongside their lead provider. We’d assume that each of these specific populations has data across the three B3 (continuation, completion, progression) indicators – in practice many of these are suppressed for the usual OfS reasons of low student numbers and (in the case of progression) low Graduate Outcomes response rates.

Where we do get indicator values we also see benchmarks and the usual numeric thresholds – the former indicating what OfS might expect to see given the student population, the latter being the line beneath which the regulator might feel inclined to get stuck into some regulating.

One thing we can’t really do with the data – although we wanted to – is treat each subcontractual provider as if it was a main provider and derive an overall indicator for it. Because many subcontractual providers have relationships (and students) from numerous lead providers, we start to get to some reasonably sized institutions. Two – Global Banking School and the Elizabeth School London – appear to have more than 5,000 higher education students: GBS is around the same size as the University of Bradford, the Elizabeth School is comparable to Liverpool Hope University.

Size and shape

How big these providers are is a good place to start. We don’t actually get formal student numbers for these places – but we can derive a reasonable approximation from the denominator (population size) for one of the three indicators available. I tend to use continuation as it gives me the most recent (2022–23) year of data.

The charts showing numbers of students are based on the denominators (populations) for one of the three indicators – by default I use continuation as it is more likely to reflect recent (2022–23) numbers. Because both the OfS and DfE consultations talk about all HE students there are no filters for mode or level.

For each chart you can select a year of interest (I’ve chosen the most recent year by default) or the overall indicator (which, like on the main dashboards is synthetic over four years) If you change the indicator you may have to change the year. I’ve not included any indications of error – these are small numbers and the possible error is wide so any responsible regulator would have to do more investigating before stepping in to regulate.

Recall that the DfE proposal is that institutions with more than 300 higher education students would have to register with OfS if they are not regulated in another way (as a school, FE college, or local authority, for instance). I make that 26 with more than 300 students, a small number of which appear to be regulated as an FE college.

You can also see which lead providers are involved with each delivery partner – there are several that have relationships with multiple universities. It is instructive to compare outcomes data within a delivery partner – clearly differences in quality assurance and course design do have an impact, suggesting that the “naive university hoodwinked by low quality franchise partner” narrative, if it has any truth to it at all, is not universally true.

The charts showing the actual outcomes are filtered by mode and level as you would expect. Note that not all levels are available for each mode of study.

This chart brings in filters for level and mode – there are different indicators, benchmarks, and thresholds for each combination of these factors. Again, there is data suppression (low numbers and responses) going on, so you won’t see every single aspect of every single relationship in detail.

That said, what we do see is a very mixed bag. Quite a lot of provision sits below the threshold line, though there are also some examples of very good outcomes – often at smaller, specialist, creative arts colleges.

Registration

I’ve flipped those two charts to allow us to look at the exposure of registered universities to this part of the market. The overall sizes in recent years at some providers won’t be of any surprise to those who have been following this story – a handful of universities have grown substantially as a result of a strategic decision to engage in multiple academic partnerships.

Canterbury Christ Church University, Bath Spa University, Buckinghamshire New University, and Leeds Trinity University have always been the big four in this market. But of the 84 registered providers engaged in partnerships, I count 44 that met the 100 student threshold for the new condition of registration B3 had it applied in 2022–23.

Looking at the outcomes measures suggests that what is happening across multiple partners is not offering wide variation in performance, although there will always be teaching provider, subject, and population variation. It is striking that places with a lot of different partners tend to get reasonable results – lower indicator values tend to be found at places running just one or two relationships, so it does feel like some work on improving external quality assurance and validation would be of some help.

To be clear, this is data from a few years ago (the most recent available data is from 2022–23 for continuation, 2019–20 for completion, and 2022–23 for progression). It is very likely that providers will have identified and addressed issues (or ended relationships) using internal data long before either we or the Office for Students got a glimpse of what was going on.

A starting point

There is clearly a lot more that can be done with what we have – and I can promise this is a dataset that Wonkhe is keen to return to. It gets us closer to understanding where problems may lie – the next phase would be to identify patterns and commonalities to help us get closer to the interventions that will help.

Subcontractual arrangements have a long and proud history in UK higher education – just about every English provider started off in a subcontractual arrangement with the University of London, and it remains the most common way to enter the sector. A glance across the data makes it clear that there are real problems in some areas – but it is something other than the fact of a subcontractual arrangement that is causing them.

Do you like higher education data as much as I do? Of course you do! So you are absolutely going to want to grab a ticket for The Festival of Higher Education on 11-12 November – it’s Team Wonkhe’s flagship event and data discussion is actively encouraged.

-

‘Right here, right now’: New report on how AI is transforming higher education

A new collection of essays, AI and the Future of Universities published by HEPI and the University of Southampton, edited by Dr Giles Carden and Josh Freeman, brings together leading voices from universities, industry and policy. The collection comes at a point when Artificial Intelligence (AI) is projected to have a profound and transformative impact on virtually every sector of society and the economy, driving changes that are both beneficial and challenging. The various pieces look at how AI is reshaping higher education – from strategy, teaching and assessment to research and professional services.

You can read the press release and access the full report here.

-

Trump’s Latest Layoffs Gut the Office of Postsecondary Ed

The Department of Education’s second round of layoffs affected nearly 500 employees and left several offices with a few or no staffers.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Tierney L. Cross/Getty Images | Matveev_Aleksandr/iStock/Getty Images

Education Secretary Linda McMahon has essentially gutted the postsecondary student services division of her department, leaving TRIO grant recipients and leaders of other college preparation programs with no one to turn to.

Prior to the latest round of layoffs, executed on Friday and now paused by a federal judge, the Student Services division in the Office of Postsecondary Education had about 40 staffers, one former OPE employee told Inside Higher Ed. Now, he and others say it’s down to just two or three.

The consequence, college-access advocates say, is that institutions might not be able to offer the same level of support to thousands of low-income and first-generation prospective students.

“It’s enormously disruptive to the students who are reliant on these services to answer questions and get the information they need about college enrollment and financial aid as they apply and student supports once they enroll,” said Antoinette Flores, a former department official during the Biden administration who now works at New America, a left-leaning think tank. “This [reduction in force] puts all of those services at stake.”

The layoffs are another blow to the federal TRIO programs, which help underrepresented and low-income students get to and through college. President Trump unsuccessfully proposed defunding the programs earlier this year, and the administration has canceled dozens of TRIO grants. Now, those that did get funding likely will have a difficult time connecting with the department for guidance.

In a statement Wednesday, McMahon described the government shutdown and the RIF as an opportunity for agencies to “evaluate what federal responsibilities are truly critical for the American people.”

“Two weeks in, millions of American students are still going to school, teachers are getting paid and schools are operating as normal. It confirms what the president has said: the federal Department of Education is unnecessary,” she wrote on social media.

This is the second round of layoffs at the Education Department since Trump took office. The first, which took place in March, slashed the department’s staff nearly in half, from about 4,200 to just over 2,400, affecting almost every realm of the agency, including Student Services and the Office of Federal Student Aid.

Nearly 500 employees lost their jobs in this most recent round, which the administration blamed on the government shutdown that began Oct. 1. No employees in FSA were affected, but the Office of Postsecondary Education was hit hard.

Jason Cottrell, a former data coordinator for OPE who worked in student and institution services for more than nine years, lost his job in March but stayed in close contact with his colleagues who remained. The majority of them were let go on Friday, leaving just the senior directors and a few front-office administrators for each of the two divisions. That’s down from about 60 employees total in September and about 100 at the beginning of the year, he said.

At the beginning of the year, OPE included five offices but now is down to the Office of Policy, Planning and Innovation, which includes oversight of accreditation, and the group working to update new policies and regulations.

Cottrell said the layoffs at OPE will leave grantees who relied on these officers for guidance without a clear point of contact at the department. Further, he said there won’t be nonpartisan staffers to oversee how taxpayer dollars are spent.

“Long-term, I’m thinking about the next round of grant applications that are going to be coming in … some of [the grant programs] receive 1,100 to 1,200 applications,” he explained. “Who is going to be there to actually organize and set up those grant-application processes to ensure that the regulations and statutes are being followed accurately?”

Flores has similar concerns.

“These [cuts] are the staff within the department that provide funding and technical assistance to institutions that are underresourced and serve some of the most vulnerable students within the higher education system,” she said. “Going forward, it creates uncertainty about funding, and these are institutions that are heavily reliant on funding.”

Other parts of the department affected by the layoffs include the Offices of Special Education and Rehabilitation Services, Communications and Outreach, Formula Grants, and Program and Grantee Support Services.

Although the remaining TRIO programs and other grant recipients that report to OPE likely already received a large chunk of their funding for the year, Cottrell noted that they often have to check in with their grant officer throughout the year to access the remainder of the award. Without those staff members in place, colleges could have a difficult time taking full advantage of their grants.

“It’s going to harm the institutions, and most importantly, it’s going to harm the students who are supposed to be beneficiaries of these programs,” he said. “These programs are really reserved for underresourced institutions and underserved students. When I look at the overall picture of what has been happening at the department and across higher education, I see this as a strategic use of an opportunity that this administration has created.”