Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Texas public school administrators, parents and education experts worry that a new law to replace the state’s standardized test could potentially increase student stress and the amount of time they spend taking tests, instead of reducing it.

The new law comes amid criticism that the State of Texas Assessment of Academic Readiness, or STAAR, creates too much stress for students and devotes too much instructional time to the test. The updated system aims to ease the pressure of a single exam by replacing STAAR with three shorter tests, which will be administered at the beginning, middle and end of the year. It will also ban practice tests, which Texas Education Agency Commissioner Mike Morath has said can take up weeks of instruction time and aren’t proven to help students do better on the standardized test. But some parents and teachers worry the changes won’t go far enough and that three tests will triple the pressure.

The law also calls for the TEA to study how to reduce the weight testing carries on the state’s annual school accountability ratings — which STAAR critics say is one reason why the test is so stressful and absorbs so much learning time — and create a way for the results of the three new tests to be factored into the ratings.

That report is not due until the 2029-30 school year, and the TEA is not required to implement those findings. Some worry the new law will mean schools’ ratings will continue to heavily depend on the results from the end-of-year test, while requiring students to start taking three exams. In other words: same pressure, more testing.

Cementing ‘what school districts are already doing’

The Texas Legislature passed House Bill 8 during the second overtime lawmaking session this year to scrap the STAAR test.

Many of the reforms are meant to better monitor students’ academic growth throughout the school year.

For the early and mid-year exams, schools will be able to choose from a menu of nationally recognized assessments approved by the TEA. The agency will create the third test. Under the law, the three new tests will use percentile ranks comparing students to their peers in Texas; the third will also assess a student’s grasp of the curriculum.

In addition, scores will be required to be released about two days after students take the exam, so teachers can better tailor their lessons to student needs.

State Sen. Paul Bettencourt, R-Houston, one of the architects behind the push to revamp the state’s standardized test, said he would like the first two tests to “become part of learning” so they can help students prepare for the end-of-year exam.

But despite the changes, the new testing system will likely resemble the current one when it launches in the 2027-28 school year, education policy experts say.

“It’s gonna take a couple of years before parents realize, to be honest, that you know, did they actually eliminate STAAR?” said Bob Popinski with Raise Your Hand Texas, an education advocacy nonprofit.

Since many schools already conduct multiple exams throughout the year, the law will “basically codify what school districts are already doing,” Popinski said.

Lawmakers instructed TEA to develop a way to measure student progress based on the results from the three tests. But that metric won’t be ready when the new testing system launches in the 2027-28 school year. That means results from the standardized tests, and their weight in the state’s school accountability ratings system, will remain similar to what they are now.

Every Texas school district and campus currently receives an A-F rating based on graduation benchmarks and how students perform on state tests, their improvement in those areas, and how well they educate disadvantaged students. The best score out of the first two categories accounts for most of their overall rating. The rest is based on their score in the last category.

The accountability ratings are high stakes for school districts, which can face state sanctions for failing grades — from being forced to close school campuses to the ousting of their democratically elected school boards.

Supporters of the state’s accountability system say it is vital to assess whether schools are doing a good job at educating Texas children.

“The last test is part of the accountability rating, and that’s not going to change,” Bettencourt said.

Critics say the current ratings system fails to take into account a lot of the work schools are doing to help children succeed outside of preparing them for standardized tests.

“Our school districts are doing a lot of interesting, great things out there for our kids,” Popinski said. “Academics and extracurricular activities and co-curricular activities, and those just aren’t being incorporated into the accountability report at all.”

In response to calls to evaluate student success beyond testing, HB 8 also instructs the TEA to track student participation in pre-K, extracurriculars and workforce training in middle schools. But none of those metrics will be factored into schools’ ratings.

“There is some other interest in looking at other factors for accountability ratings, but it’s not mandated. It’s just going to be reviewed and surveyed,” Bettencourt said.

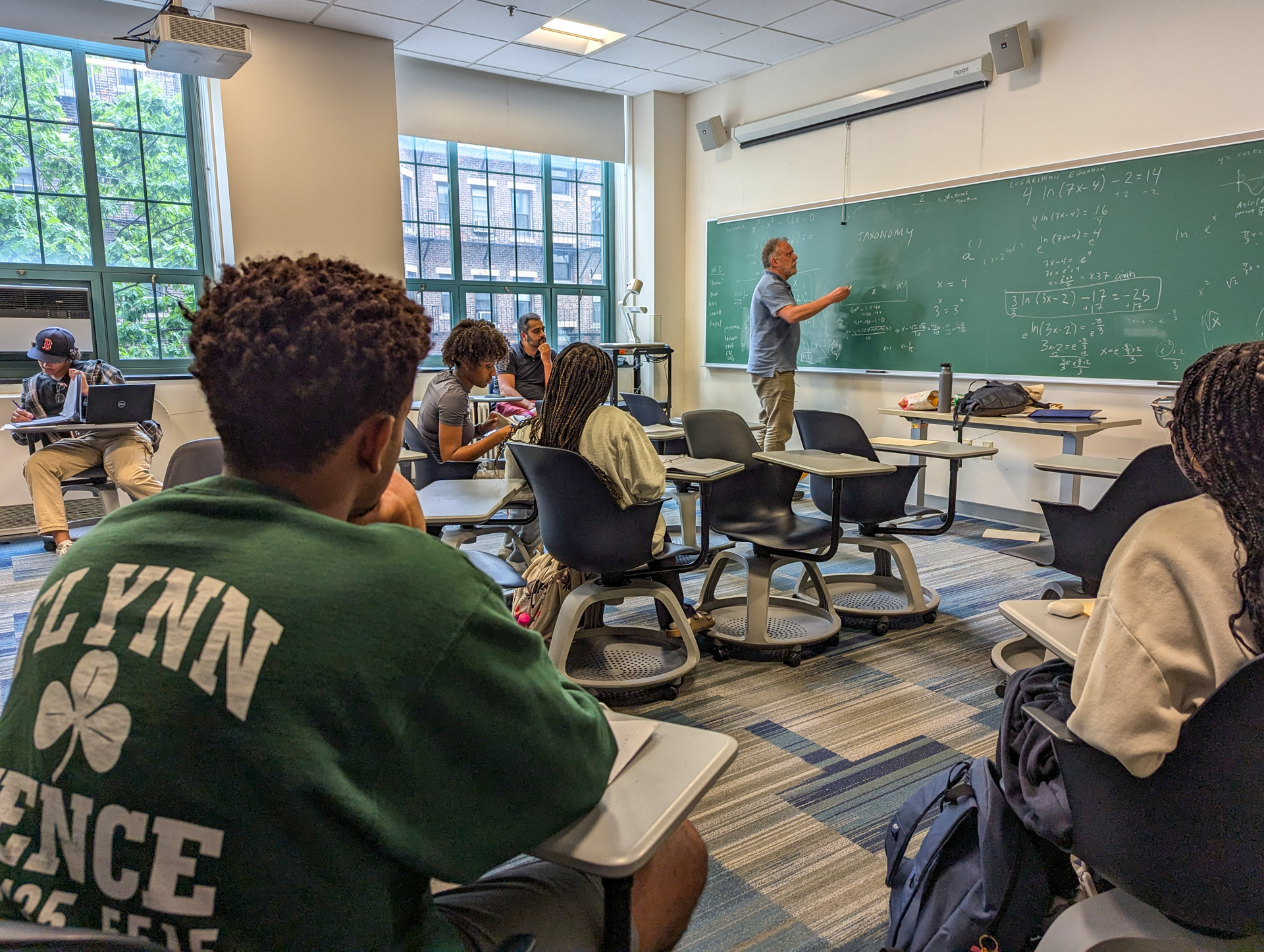

Student stress worries

Even though many schools already conduct testing throughout the year, Popinski said the new system created by HB 8 could potentially boost test-related stress among students.

State Rep. Brad Buckley, R-Salado, who sponsored the testing overhaul in the Texas House, wrote in a statement that “TEA will determine testing protocols through their normal process.” This means it will be up to TEA to decide whether to keep or change the rules that it currently uses for the STAAR test. Those include that schools dedicate three to four hours to the exam and that administrators create seating charts, spread out desks and manage restroom breaks.

School administrators said the worst-case scenario would be if all three of the new tests had to follow lockdown protocols like the ones that currently come with STAAR. Holly Ferguson, superintendent of Prosper ISD, said the high-pressure environment associated with the state’s standardized test makes some of her students ill.

“It shouldn’t be that we have kids sick and anxiety is going through the roof because they know the next test is coming,” Ferguson said.

The TEA did not respond to a request for comment.

HB 8 also seeks to limit the time teachers spend preparing students for state assessments, partly by banning benchmark tests for 3-8 grades. Bettencourt told the Tribune the new system is expected to save 22.5 instructional hours per student.

Buckley said the new law “will reduce the overall number of tests a student takes as well as the time they spend on state assessments throughout the school year, dramatically relieving the pressure and stress caused by over-testing.”

But some critics worry that any time saved by banning practice tests will be lost by testing three times a year. In 2022, Florida changed its testing system from a single exam to three tests at the beginning, middle and end of the year. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis said the new system would reduce test time by 75%, but the number of minutes students spent taking exams almost doubled the year the new system went into effect.

Popinski added that much of the stress the test induces comes from the heavy weight the end-of-year assessment holds on a school’s accountability rating. The pressure to perform that the current system places on school district administrators transfers to teachers and students, critics have said.

“The pressures are going to be almost exactly the same,” Popinski said.

What parents, educators want for the new test

Retired Fort Worth teacher Jim Ekrut said he worries about the ban on practice tests, because in his experience, test preparations helped reduce his students’ anxiety.

Ekrut said teachers’ experience assessing students is one reason why educators should be involved in creating the new end-of-year exam.

“The better decisions are going to be made with input from people right on that firing line,” Ekrut said.

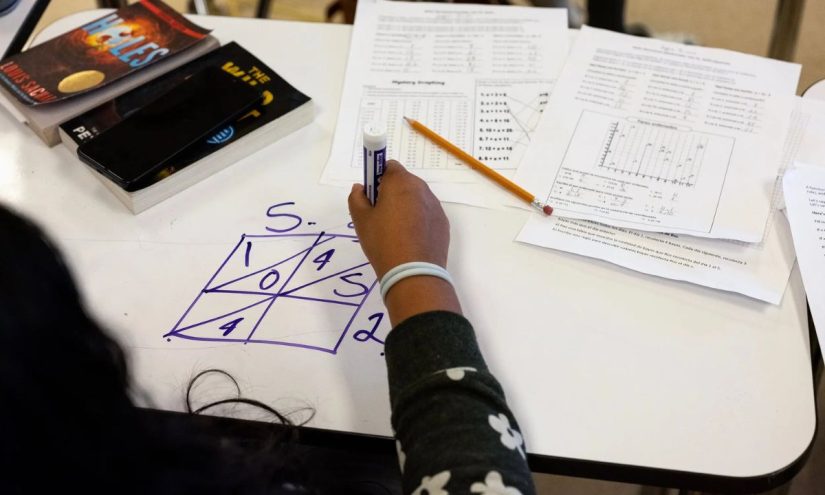

HB 8 requires that a committee of educators appointed by the commissioner reviews the new test that TEA will create. Some, like Ferguson and David Vinson, former superintendent of Wylie ISD who started at Conroe this week, said they hope the menu of possible assessments districts can pick for the first two tests includes a national program they already use called Measures of Academic Progress, or MAP.

The Prosper and Wylie districts are some that administer MAP exams at the beginning, middle and end of the year. More than 4,500 school districts nationwide use these online tests, which change the difficulty of the questions as students log their answers to better assess their skill level and growth. A 2024 study conducted by the organization that runs MAP found that the test is a strong indicator of how students perform on the end-of-year standardized test.

Criteria-based tests like STAAR measure a student’s grasp on grade-level skills, whereas norm-based exams like MAP measure a student’s growth over the course of instruction. Vinson described this program as a “checkup,” while STAAR is an “autopsy.”

Rachel Spires, whose children take MAP tests at Sunnyvale ISD, said MAP testing doesn’t put as much pressure on students as STAAR does.

Spires said her children’s schedules are rearranged for the month of April, when Sunnyvale administers the STAAR test, and parents are barred from coming to campus for lunch. MAP tests, on the other hand, typically take less time to complete, and the school has fewer rules for how they are administered.

“When the MAP tests come around, they don’t do the modified schedules, and they don’t do the review packets and prep testing or anything like that,” Spires said. “It’s just like, ‘Okay, tomorrow you’re gonna do a MAP test,’ and it’s over in like an hour.”

For Ferguson, the Prosper ISD superintendent, a relaxed environment around testing is key to achieving the new law’s goal of reducing student stress.

“If it’s just another day at school, I’m all in,” Ferguson said. “But if we lock it down, and we create a very compliance-driven system that’s very archaic and anxiety- and worry-inducing to the point that it starts having potential harmful effects on our kids … our teachers and our parents, I’m not okay with that.”

This article originally appeared in The Texas Tribune at https://www.texastribune.org/2025/09/24/texas-staar-replacement-map-testing/. The Texas Tribune is a member-supported, nonpartisan newsroom informing and engaging Texans on state politics and policy. Learn more at texastribune.org.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter