Almost all employees at the University of New England (UNE) use AI each day to augment tasks, despite the wider sector slowly adopting the tech into its workforce.

Please login below to view content or subscribe now.

Membership Login

Almost all employees at the University of New England (UNE) use AI each day to augment tasks, despite the wider sector slowly adopting the tech into its workforce.

Please login below to view content or subscribe now.

University of the Sunshine Coast pro-vice-chancellor (global and engagement) Alex Elibank-Murray and technology lead Associate Professor Rania Shibl share their experiences of partnerships with industry to enhance student experience in fast-changing fields.

Please login below to view content or subscribe now.

As the new academic year approaches, universities across the UK are gearing up to welcome thousands of new students.

The first week on campus is all about helping students feel welcome, and evidence shows that this transition period is crucial for fostering a sense of belonging.

But why should we care about fostering belonging in our students? Well, belonging is a basic human need and central to our wellbeing. Belonging is predominantly about social relationships, but also the environment, cultural groups, and physical places we reside in. That is, belonging is about all areas of life.

For university students, a sense of belonging at their institutions is one of the key factors to help them get the most out of their degree. Students who report a strong sense of belonging to their university course often experience better mental health and general wellbeing.

Worryingly, however, there is a lack of focus on postgraduate taught (PGT) students within the belonging literature. It is perhaps easy to assume that because PGTs have made the transition to university already, they will find the transition to the next level of study easy. But from the (limited) research out there, the transition from undergraduate to PGT is just as challenging, and surveys exploring wellbeing consistently reveal PGT students have poor, and sometimes the worst, wellbeing levels of any student cohort.

PGT students are also overlooked more broadly across the higher education landscape. There is heavy weighing on the importance of the National Student Survey (NSS) which explores undergraduate student experience. The NSS is highly influential, publicly published and discussed in the media and league tables. In contrast, the (optional) Postgraduate Taught Experience Survey (PTES) is much less visible and has much lower response rates. The response in 2024 was proudly published as the highest ever response rate at 13 per cent of the UK PGT student population. The 2024 NSS achieved a 72.3 per cent response rate. This may be in part due to the visibility of the PTES, and shorter course length, but could also reflect a weaker sense of belonging in these cohorts.

Taken together, it seems as though PGT students often feel a weak sense of belonging on their courses and are overlooked by the sector. As a staff member working closely with PGT students, and a PGT student who has suffered a lack of belonging, we recognised the issue and noted the lack of clear guidance for educators to start thinking about these issues in their own settings.

We therefore produced a free guide for educators to consider PGT belonging in their own contexts. The guide is available to download for free from the Open Science Framework (OSF).

In the guide, we have outlined what belonging is, why it is so crucial for all students, but we have a particular focus on PGT students. We have also provided prompts for educators to reflect on their current practice, with the aim of inspiring staff to identify opportunities for increasing belonging.

We have provided 5 simple evidence-based recommendations that educators can make now to work towards increased belonging in PGT students, which we will highlight in turn here. The first recommendation is around language and communication. PGT students report feeling that a lot of the generic information received from university was tailored to their undergraduate peers. Simple rewording for each cohort receiving the emails would really help students feel seen and valued.

And staff need to develop an awareness of the cohort diversity. Some students will be entering straight after undergraduate, but many return to study after time away which can be challenging. PGT students have higher tuition fees and typically no separate maintenance loan, thus it is common for these students to have work commitments alongside their studies. PGT students are expected to learn independently at a higher level, often within just a year. Many universities run conversion courses, allowing students to change discipline. This can mean grappling with a different epistemology, which is a unique challenge.

Ideally, staff should provide appropriate levels of support to the unique needs of the cohort. One way in which this tailored support could be provided is through informal upskilling workshops to ensure students understand the expectations of the programme. These could be run by the school, department, or centrally.

The final two recommendations centre around the ability to form social connections. PGT students feel that due to such full timetables, they have limited opportunities to develop connections with their peers. Scheduling opportunities for PGT students to socialise, particularly when they are already on campus, can help develop those much-needed social connections. For instance, holding a regular coffee morning or study session can mean students have a space to work and socialise in between teaching sessions.

Students also need to develop meaningful relationships with teaching staff. When staff actively schedule and attend student events, they help cultivate authentic relationships that enhance student engagement. These informal social opportunities can nurture a community feeling.

With all this in mind, how will you ensure your next cohort of PGT students feels a sense of belonging? Download the guide, reflect on your practice, and start making small, meaningful changes – because every student deserves to feel that they belong.

At its core, full-funnel marketing means investing in upper-funnel awareness and mid-funnel consideration strategies to drive lead generation efforts and investing in post-inquiry marketing to continue to nurture prospects into students.

While we like to think of the student journey as a linear process and clear path that every student follows, the reality is that every student journey is unique, and it rarely follows the exact path we proscribe. In spite of this reality, it is helpful to understand the stages of the journey that all prospective students must go through in some form. Understanding the stages of the student journey allows us to deploy a full funnel approach to our marketing and enrollment management efforts – one that takes a holistic approach and creates a student-centered experience that is more likely to result in better outcomes for your marketing efforts and ultimately your students.

Rather than focusing marketing efforts on lead generation efforts, a full funnel marketing approach invests in upper funnel activities and post-inquiry student engagement opportunities. Upper funnel marketing builds awareness and educates prospective future students. Down funnel pre-post-inquiry marketing nurtures prospective students, builds a relationship and helps the student move from consideration to enrollment and graduation.

In this article we will discuss the following topics:

The student enrollment funnel is a critical framework for understanding the path prospective students take from initial awareness to becoming enrolled students. By recognizing the key stages and the specific needs of students at each point, institutions can tailor their outreach and support to maximize enrollment success.

Here’s a breakdown of the key stages of the student enrollment funnel:

1. Awareness: The Brand Foundation

When prospective students are just starting to consider higher education or specific programs, they are forming their first impressions on a variety of universities. This broad stage is your institution’s opportunity to grab their attention and inform them of who you are. The goal here is the craft and deliver messaging that excites your prospective students to learn more and easing them into the next stages of their decision-making journey.

You must lead with your brand story and values. This is where you establish your reputation as a forward-thinking innovator, a career catalyst or a community builder. Use powerful visual storytelling on social and video. Use organic content to expose the authentic student experience. This is how you bypass the noise and build a foundation of trust before a student even knows your name.

Grab the attention of these prospective students so that they’re aware of your institution through these channels:

Crafting and delivering messaging that focuses on your institution’s unique strengths such as innovative programs, a vibrant campus life, outstanding online options, or personalized student support can be beneficial for guiding potential students through the early stages of their decision-making journey.

2. Consideration: The Value Proposition

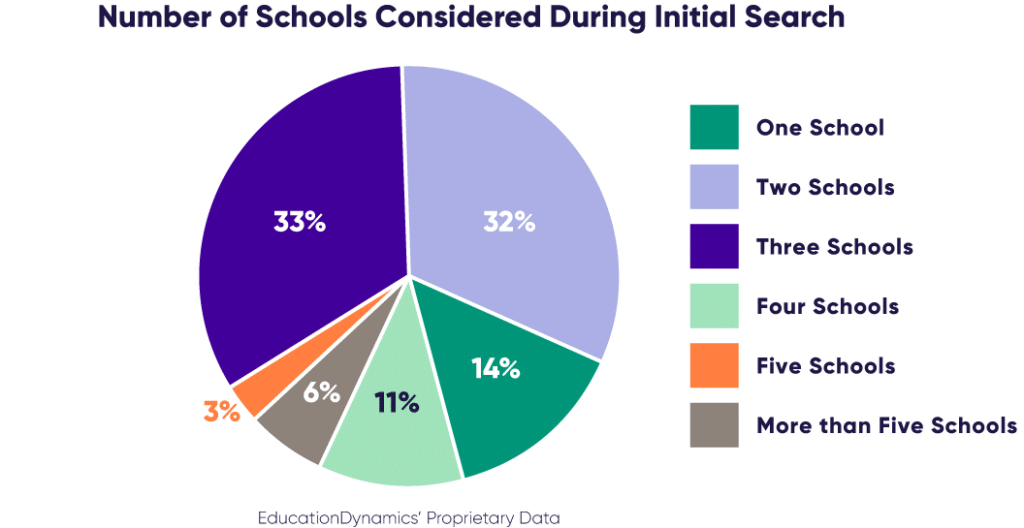

At this stage, students have narrowed their focus to a few institutions and are actively researching their options. This consideration stage is recognized as the longest in the student journey, lasting from the moment they first become aware of colleges all the way through enrollment. During this extended period, prospective students constantly revisit and refine their choices, narrowing down their top pick schools. According to our latest Engaging the Modern Learner Report, a majority of students have at most three schools in their consideration set. This highlights the importance of maintaining engagement throughout this critical phase.

The content here must prove your value. Forget the general brochures. Provide dynamic, personalized content that highlights your reputation in a way that’s relevant to the student’s specific interests. If you’re known for a top-tier nursing program, the content must show career outcomes, job placements and alumni stories. This is about converting curiosity into tangible desire by connecting your brand promise to a student’s personal ambition.

Highlight your strengths through informative content across various channels:

By providing informative, clear and confidence-building content that addresses student concerns, your institution can increase its visibility and solidify your institution as a top contender in the prospective student’s final selection process.

3. Conversion: The Proof of Promise

Prospective students compare their top choices and make their final decision. The communication strategy here should focus on addressing the prospective student’s final concerns, offering reassurance and providing clear and accessible information about their next steps.

During the conversion phase of the student enrollment funnel, prioritize creating a frictionless experience. By offering clear communication, readily available resources, and a streamlined application process, you can significantly increase your chances of converting prospective students into enrolled students, solidifying their decision to choose your institution.

Your admissions process is not just an application. It is a live reflection of your brand. The communication must be consistent with the brand promise. If your reputation is built on student-centric support, every email, phone call and text must be empathetic and helpful. Use hyper-personalized messaging and AI-powered tools that make the student feel heard and valued. The goal is to make the application feel like the first step in a personalized relationship not the end of a transaction.

Channels for increasing the likelihood of conversion during the conversion phase:

By providing clear guidance, addressing concerns and showcasing the value proposition of your institution, you can ensure a seamless transition from prospective student to applicant.

4. Lead Nurturing: Sustaining the Connection

Your institution has successfully captured the attention of prospective students and established an initial connection. At this stage, students are dedicating time to carefully consider their top options for advancing their education. Maintain and deepen prospective students’ interest by delivering messaging that is personalized, detailed and addresses each prospect’s specific concerns and questions. The key to a successful lead nurturing strategy is to provide a supportive, no-pressure environment while supporting their decision-making process and nudging them closer to taking the next step with your school.

This is where you double down on your brand. Your nurturing strategy should not just remind students of deadlines. It should make them feel like a part of your community before they ever set foot on campus. Use targeted campaigns that introduce them to their future classmates, faculty and student support services. Reinforce the values they fell in love with during the awareness stage. This mitigates “melt” and transforms an accepted student into an enrolled student.

Channels that can maximize your lead nurturing efforts include:

Truly cultivate an understanding and support for prospective students navigating through the application process by delivering messaging that inspires them to complete their educational journey, personalized guidance and reminds them of the enriching experiences that await them at your institution.

5. Enrollment: The Starting Line

At this stage, prospective students have become applicants, now it’s a matter of getting them to enroll and move forward at your institution. Offering content that effectively addresses any final concerns and provides reassurance that their decision to enroll at your institution is the right choice, right fit and right time for them.

Enrollment is not the end of the funnel. It’s the beginning of a lifetime of brand loyalty. Acknowledge and celebrate this moment. Use this stage to welcome them to the community and prepare them for their new life as a student and future advocate for your brand.

Convert your applicants into enrolled students with these channels:

Feature content that addresses barriers such as affordability, mental burnout, and enrollment complexity by highlighting the availability of financial aid, scholarships, flexible payment options and personalized support services to promote streamlined enrollment process.

Utilizing email and SMS will be the most effective in delivering this type of content. Incorporating strategies such as targeted email campaigns and personalized phone calls can be effective. As long as the content you are offering provides clear and easy-to-follow instructions for the enrollment process, your institution can help eliminate any confusion or frustration and solidifying that the students’ decision to enroll at your school was the right one.

At EducationDynamics, we have always taken a holistic approach to student recruitment and believe it is essential for long-term growth and sustainability. We have seen several shifts in the landscape that make a full-funnel marketing strategy more valuable than ever before.

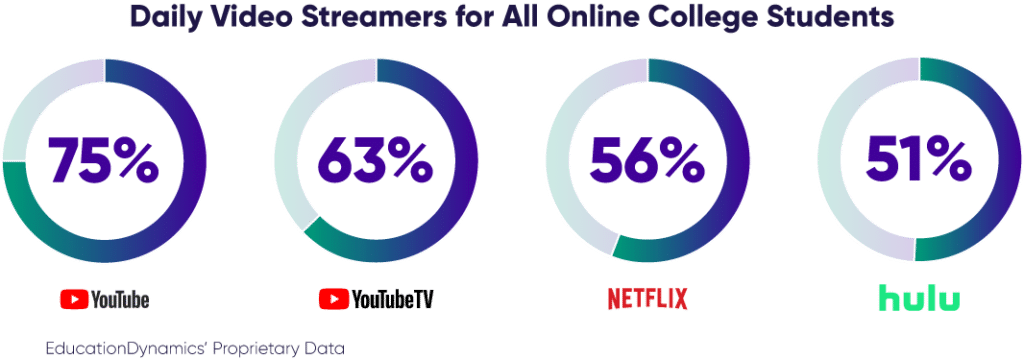

First, we see increasing complexity in the media landscape, from consumer behavior to advances in marketing channels. The average number of streaming hours consumed continues to rise. At the same time, ad-supported streaming platforms are growing in popularity and the social media landscape is fragmenting. In our latest Online College Students Report 2024, about 70% of online college students utilize primarily ad-supported streaming services and use YouTube, Spotify, YouTube TV, Netflix, and Hulu daily. These landscape changes are important in that they tell a story about where prospective students are spending their time online and how we can effectively reach them with advertising.

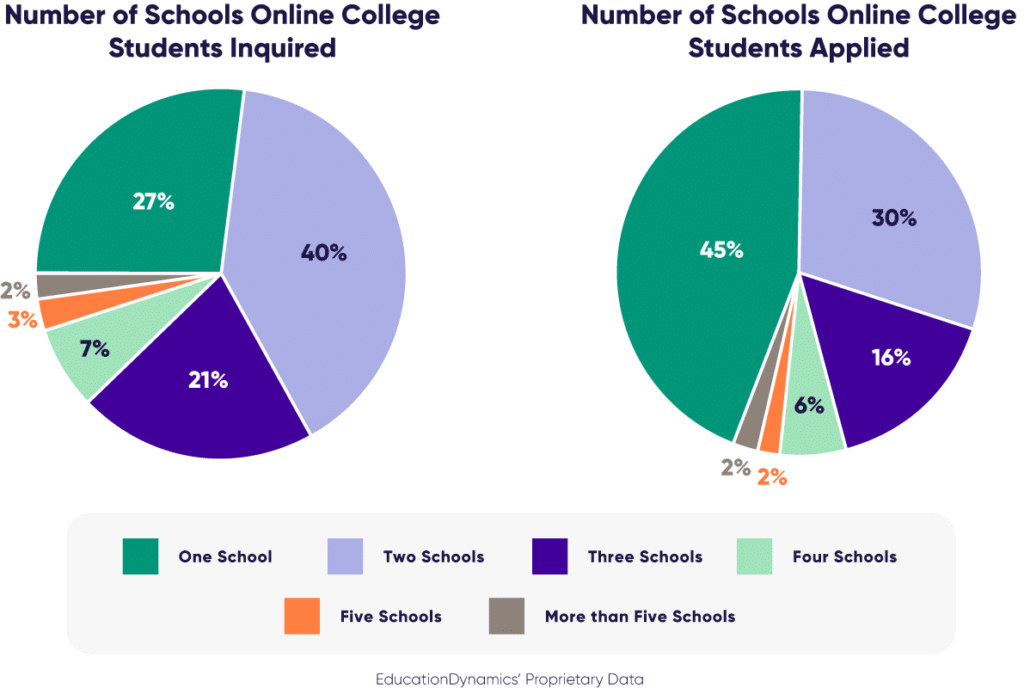

Secondly, we are seeing changes in how prospective students are searching for and making decisions about higher education. As the focus on student loan debt and the value of higher education continues to be top of mind for students, we are seeing this manifest in prospective students doing more research even after the point of inquiry. In our 2024 Online College Students Report, 40% of online college students initially inquired at two schools and 21% inquired at three. Once they narrowed their selection 30% of online college students applied to two schools and 16% applied to three. Students are motivated to find the best value. They are therefore continuing to research past the point of inquiry and application to confirm their decision to invest—not just in tuition, but also their time and energy. Higher education marketers aim to respond by continuing to leverage various marketing channels to keep schools in the mix and reassure students why these schools are right for them and their circumstances.

With all these changes in the market, winning universities and colleges are shifting their marketing strategies to meet this dynamic environment. By implementing a full-funnel marketing approach, institutions can benefit from:

By embracing a full-funnel strategy, institutions can effectively navigate the complex media landscape, address the evolving needs of prospective students, and ultimately achieve their enrollment goals.

While the execution of a full-funnel marketing approach will vary depending on the institution, there’s a common thread: measuring success through Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) tailored to each stage of the funnel. This means monitoring and measuring the micro-conversions and engagements along the journey in addition to the more obvious traditional conversion points like requests for information, application and enrollment.

Here’s a breakdown of KPIs for different funnel stages:

There are two types of ‘Mid-Funnel’ stages in higher education marketing. We refer to the portion of the stage where the focus of marketing is on lead generation as pre-inquiry activities. Whereas, in admissions, enrollment and new student starts are the goal. We refer to this portion of the stage post-inquiry activities.

Pre-inquiry activities include efforts made to connect with prospective students prior to directly contacting an institution for information. When tracking the effectiveness of these activities, higher ed marketers may consider these key metrics to determine their strategies’ ability to attract, engage and convert prospective students:

Following prospective students’ application submissions, your institution should prioritize a smooth transition into enrollment. A frictionless enrollment streamlines the process, ensuring a higher conversion rate while enhancing the overall student experience. To track the effectiveness of your post-inquiry activities, consider the following metrics:

Monitoring these KPIs across the funnel stages provides valuable insights into the effectiveness of your full-funnel marketing strategy. This allows for data-driven adjustments to optimize each stage and ultimately improve your return on investment (ROI) for student recruitment.

By incorporating the costs associated with all stages of the funnel, you can leverage blended cost-per-enrollment (CPE) metrics. This provides a more holistic view of marketing effectiveness and allows you to utilize directional or causal analyses. These techniques go beyond simply observing correlations between upper funnel activities (such as brand awareness campaigns) and lead generation/bottom funnel results (like applications). They can help you understand the cause-and-effect relationships between these stages. Directional analyses can point you in the right direction, while causal analyses can provide more definitive evidence of the indirect impact that upper funnel activities have on lead generation and bottom funnel results.

As prospective students continue to search for higher education options and make decisions based on value, it is crucial for institutions to adapt their marketing strategies to meet this demand. Embracing a full-funnel approach will ensure that institutions stay competitive in the higher education market and achieve their enrollment goals.

Are you ready to transform your transform your marketing strategy to grow enrollment? Start a conversation with EducationDynamics today to discuss how we can help you implement a customized full-funnel strategy that drives enrollment growth and achieves your unique goals.

Edan Kauer is a former FIRE intern and a sophomore at Georgetown University.

Elliston Berry was just 14 years old when a male classmate at Aledo High in North Texas used AI to create fake nudes of her based on images he took from her social media. He then did the same to seven other girls at the school and shared the images on Snapchat.

Now, two years later, Berry and her classmates are the inspiration for Senator Ted Cruz’s Take It Down Act (TIDA), a recently enacted law which gives social media platforms 48 hours to remove “revenge porn” once reported. The bill considers any non-consensual intimate imagery (NCII), including AI deepfakes, to fall under this category. But despite the law’s noble intentions, its dangerously vague wording is a threat to free speech.

This law, which covers both adults and minors, makes it illegal to publish an image of an identifiable minor that meets the definition of “intimate visual depiction,” which is defined as certain explicit nudity or sexual conduct, with intent to “arouse or gratify the sexual desire of any person” or “abuse, humiliate, harass, or degrade the minor.”

FIRE offers an analysis of frequently asked questions about artificial intelligence and its possible implications for free speech and the First Amendment.

That may sound like a no-brainer, but deciding what content this text actually covers, including what counts as “arousing,” “humiliating,” or “degrading” is highly subjective. This law risks chilling protected digital expression, prompting social media platforms to censor harmless content like a family beach photo, sports team picture, or images of injuries or scars to avoid legal penalties or respond to bad-faith reports.

Civil liberties groups such as the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) have noted that the language of the law itself raises censorship concerns because it’s vague and therefore easily exploited:

Take It Down creates a far broader internet censorship regime than the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), which has been widely abused to censor legitimate speech. But at least the DMCA has an anti-abuse provision and protects services from copyright claims should they comply. This bill contains none of those minimal speech protections and essentially greenlights misuse of its takedown regime … Congress should focus on enforcing and improving these existing protections, rather than opting for a broad takedown regime that is bound to be abused. Private platforms can play a part as well, improving reporting and evidence collection systems.

Nor does the law cover the possibility of people filing bad-faith reports.

In the 2002 case Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition, the Court said the language of the Child Pornography Protection Act (CPPA) was so broad that it could have been used to censor protected speech. Congress passed the CPPA to combat the circulation of computer-generated child pornography, but as Justice Anthony Kennedy explained in the majority opinion, the language of the CPPA could be used to censor material that seems to depict child pornography without actually doing so.

While we must acknowledge that online exploitation is a very real issue, we cannot solve the problem at the expense of other liberties.

Also in 2002, the Supreme Court heard the case Ashcroft v. ACLU, which came about after Congress passed the Child Online Protection Act (COPA) to prevent minors from accessing adult content online. But again, due to the broad language of the bill, the Court found this law would restrict adults who are within their First Amendment rights to access mature content.

As with the Take It Down Act, here too were laws created to protect children from sexual exploitation online, yet established using vague and overly broad standards that threaten protected speech.

But unfortunately, stories like the one at Aledo High are becoming more common as AI becomes more accessible. Last year, boys at Westfield High School in New Jersey used AI to circulate fake nudes of Francesca Mani, who is 14 years old, and other girls in her class. But Westfield High administrators were caught off guard as they had never experienced this type of incident. Although the Westfield police were notified and the perpetrators were suspended for up to 2 days, parents criticized the school for their weak response.

A year later, the school district developed a comprehensive AI policy and amended their bullying policy to cover harassment carried out through “electronic communication” which includes “the use of electronic means to harass, intimidate, or bully including the use of artificial intelligence “AI” technology.” What’s true for Westfield High is true for America — existing laws are often more than adequate to deal with emerging tech issues. By classifying AI material under electronic communication as a category of bullying, Westfield High demonstrates that the creation of new AI policies are redundant. On a national scale, the same can be said for classifying and prosecuting instances of child abuse online.

While we must acknowledge that online exploitation is a very real issue, we cannot solve the problem at the expense of other liberties. Once we grant the government the power to silence the voices we find distasteful, we open the door to censorship. Though it is essential to address the very real harms of emerging AI technology, we must also keep our First Amendment rights intact.

This article originally appeared in USA Today on Sept. 21, 2025.

If you’re a believer in free speech, the past two weeks have been one of the longest years of your life. In fact, this might have been the worst fortnight for free expression in recent memory.

It started Sept. 9, when the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), where I work, released its sixth annual College Free Speech Rankings. The rankings revealed that a record 1 out of 3 students is open to the idea of using violence to stop campus speech.

This sentiment was then frighteningly made flesh the next day, when conservative commentator Charlie Kirk was assassinated at Utah Valley University.

The fact that Kirk was killed while engaging in open debate on a college campus is a cruel irony. If the first person to hurl an insult rather than a spear birthed civilization, then anyone resorting to violence in response to speech is attempting to abort it.

The free speech principles that are foundational to our democracy have been a candle in the dark – not just here at home, but across a world in the grip of a terrifying resurgence of authoritarianism.

The difference between words and violence – and the civilizational importance of free speech – couldn’t have been more stark in that moment. No matter how hurtful, hateful or wrong, there is no comparing words to a bullet.

To preserve that distinction, we must have the highest possible tolerance for even the ugliest speech. But that notion has landed on largely deaf ears, because what followed was a cacophony of cancellations.

Scores of college professors, for example, have either been investigated, suspended or fired for comments they made regarding Kirk’s assassination. Even wildlife conservationists, comic book writers, retail workers and restaurant employees have been targeted for their speech.

There are many more, and Vice President JD Vance, while stepping in to guest-host “The Charlie Kirk Show,” endorsed these efforts.

In some cases, the targeted speech was a criticism of Kirk and his views. In others, it was a celebration of his fate. In all cases, however, it has been First Amendment-protected speech – and far from violence.

The government pressure didn’t end there, either. Secretary of Agriculture Brooke Rollins called for “a legal and rational crackdown on the forces that are desperately trying to annihilate our nation.”

ABC suspended Jimmy Kimmel hours after FCC Chair Brendan Carr suggested they could face consequences for remarks Kimmel made in the aftermath of Charlie Kirk’s murder.

On Sept. 15, U.S. Attorney General Pam Bondi went on “The Katie Miller Podcast” and threatened, “There’s free speech, and then there’s hate speech. . . . We will absolutely target you, go after you, if you are targeting anyone with hate speech.”

Given that there is no First Amendment exception or legal definition for “hate speech,” this can mean just about anything Bondi and President Donald Trump‘s administration consider “hateful.” Bondi walked back her comments after public outcry, notably from conservatives.

The president, however, ran with it, threatening an ABC News reporter for having covered him “unfairly.” “You have a lot of hate in your heart,” Trump said Sept. 16. “Your company paid me $16 million for a form of hate speech. So maybe they’ll have to go after you.”

Then Federal Communications Commission Chairman Brendan Carr publicly threatened action against host Jimmy Kimmel and ABC for “really sick” comments Kimmel made during his opening monologue. “We can do this the easy way or the hard way,” Carr said.

Hours later, ABC suspended Kimmel’s show indefinitely, prompting celebration from Trump, Carr and others – and driving us from a free speech nightmare into a full-on hellscape.

This is unsustainable.

In the past two weeks alone, the state of free speech in our country has been battered almost beyond recognition.

For years now, we have had a cultural climate where growing numbers of people are so intolerant of opposing viewpoints that they will resort to violence, threats and cancellation against their adversaries. Now we’re seeing the Trump administration flagrantly abusing its power and authority to punish criticism and enforce ideological conformity.

Yes, plenty of previous administrations have violated the First Amendment. But rather than repudiating those violations, the Trump administration’s actions over the past week have dramatically escalated how openly and aggressively that constitutional line is crossed.

The core American belief that power is achieved through persuasion and the ballot box, and that bad ideas are beaten by better ones – not by bullets or bullying – is in serious danger.

As former federal Judge Learned Hand once put it: “Liberty lies in the hearts of men and women; when it dies there, no constitution, no law, no court can even do much to help it.”

That’s what’s at stake here: The free speech principles that are foundational to our democracy have been a candle in the dark – not just here at home, but across a world in the grip of a terrifying resurgence of authoritarianism.

The ultimate tragedy would be if we extinguished them in our own hearts and by our own hands.

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) released its annual stat fest, Education at a Glance (EAG), two weeks ago and I completely forgot about it. But since not a single Canadian news outlet wrote anything about it (neither it nor the Council of Ministers of Education, Canada saw fit to put together a “Canada” briefing, apparently), this blog – two weeks later than usual – is still technically a scoop.

Next week, I will review some new data from the Programme for International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) that was released in EAG and perhaps – if I have time – some data from EAG’s newly re-designed section on tertiary-secondary. Today, I am going to talk a bit about some of the data on higher education and financing, and specifically, how Canada has underperformed the rest of the developed world – by a lot – over the past few years.

Now, before I get too deep into the data, a caveat. I am going to be providing you with data on higher education financing as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product. And this is one of those places where OECD really doesn’t like it when people compare data across various issues of EAG. The reason, basically, is that OECD is reliant on member governments to provide data, and what they give is not consistent. On this specific indicator, for instance, the UK data on public financing of higher education are total gibberish, because the government keeps changing its mind on what constitutes “public funding” (this is what happens when you run all your funding through tuition fees and student loans and then can’t decide how to describe loan forgiveness in public statistics). South Korea also seems to have had a re-think about a decade ago with respect to how to count private higher education expenditure as I recounted back here.

There’s another reason to be at least a little bit skeptical about the OECD’s numbers, too: it’s not always clear what is and is not included in the numbers. For instance, if I compare what Statistics Canada sends to OECD every year with the data it publishes domestically based on university and college income and on its own GDP figures, I never come up with exactly the same number (specifically, the public spending numbers it provides to OECD are usually higher than what I can derive from what is presumably the same data). I suspect other countries may have some similar issues. So, what I would remind everyone is simply: take these numbers as being broadly indicative of the truth, but don’t take any single number as gospel.

Got that? OK, let’s look at the numbers.

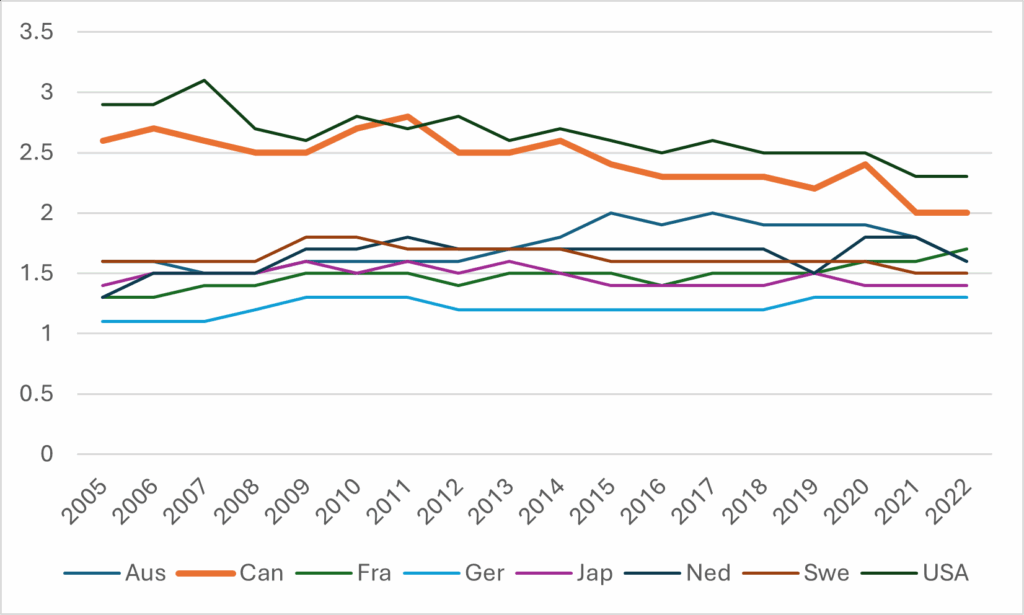

Figure 1: Public and Private Expenditure on Tertiary Institutions as a Percentage of GDP, Select OECD Countries, 2022

Canada on this measure looks…OK. Public expenditure is a little bit below the OECD average, but thanks to high private expenditure, it’s still significantly above the average. (Note, this data is from before we lost billions of dollars to a loss of international student fees, so presumably the private number is down somewhat since then). We’re not Chile, we’re not the US or the UK, but we’re still better than the median.

Which is true, if all you’re looking at is the present. Let’s go look at the past. Figure 2, below, shows you two things. First, the amount of money a country spends on its post-secondary education system usually doesn’t change that much. In most countries, in most years, moving up or down one-tenth of a percentage point is a big deal, and odds are even over the course of a decade or so, your spending levels just don’t change that much.

Figure 2: Total Expenditure on Tertiary Institutions as a Percentage of GDP, Select OECD Countries, 2005-2022

Second, it shows you that in both Canada and the United States, spending on higher education, as a percentage of the economy, is plummeting. Now, to be fair, this seems like more of a denominator issue than a numerator issue. Actual expenditures aren’t decreasing (much) but the economy is growing, in part due to population growth, which isn’t really happening in the same way in Europe.

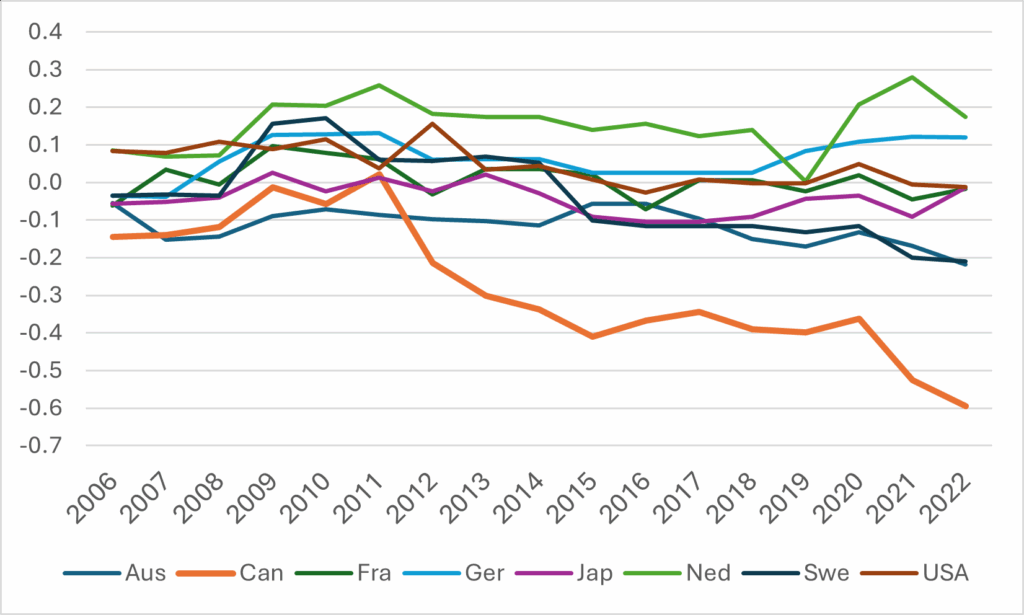

There is a difference between the US and Canada, though. And that is where the decline is coming from. In the US, it is coming (mostly) from lower private-sector contributions, the result of a decade or more of tuition restraint. In Canada, it is coming from much lower public spending. Figure 3 shows change in public spending as a percentage of GDP since 2005.

Figure 3: Change in Public Expenditure on Tertiary Institutions as a Percentage of GDP since 2005, Select OECD Countries, 2006-2022

As you can see here, few countries are very far from where they started in terms of spending as a percentage of GDP per capita. Australia and Sweden are both down a couple of tenths of a percentage point. Lucky Netherlands is up a couple of tenths of a percentage point (although note this is before the very large cutbacks imposed by the coalition government last year). But Canada? Canada is in a class all of its own, down 0.6% of GDP since just 2011. (Again, don’t take these numbers as gospel: on my own calculations I make the cut in public funding a little bit less than that – but still at least twice as big a fall as the next-worst country).

In sum: Canada’s levels of investment in higher education are going the wrong way, because governments of all stripes at both the federal and provincial level have thought that higher education is easily ignorable or not worth investing in. As a result, even though our population and economy are growing, universities and colleges are being told to keep operating like it’s 2011. The good news is that we have a cushion: we were starting from a pretty high base, and for many years we had international student dollars to keep us afloat. As a result, even after fifteen years of this nonsense, Canada’s levels of higher education investment still look pretty good in comparison to most countries. The bad news: now that the flow of international student dollars has been reduced, the ground is rising up awfully fast.

In 1857, Herman Melville published The Confidence-Man: His Masquerade, a cryptic, satirical novel set aboard a Mississippi steamboat. The titular character—ever-shifting, ever-deceiving—exploits the trust of passengers in a society obsessed with profit, spectacle, and moral ambiguity. That same year, the United States plunged into its first global financial crisis, the Supreme Court issued the Dred Scott decision denying citizenship to Black Americans, and violence erupted in Kansas over slavery. The nation was expanding westward while morally imploding.

Fast forward to 2025, and the parallels are chilling.

The Panic of 1857 was triggered by speculative bubbles, banking failures, and the sinking of a gold-laden ship meant to stabilize Eastern banks. In 2025, the U.S. faces a different kind of panic: record-high debt servicing costs, a fragile labor market dominated by gig work, and a public increasingly skeptical of financial institutions. The Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), led by Elon Musk, has slashed federal jobs and privatized public services, echoing the confidence games of Melville’s era.

Trust—once the bedrock of civic life—is now a currency in freefall.

In 1857, the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision shattered any illusion of unity. Today, the return of Donald Trump to the presidency has reignited deep political divisions. Executive orders, agency dismantling, and immigration crackdowns have triggered constitutional challenges reminiscent of the 1850s. The rule of law feels increasingly negotiable.

Higher education institutions, once bastions of reasoned debate, now find themselves caught between political polarization and economic precarity. Faculty are pressured to conform, students are surveilled, and public trust in academia is eroding.

Melville’s confidence man sold fake medicines and bogus charities. In 2025, deception is digitized: AI-generated content, deepfakes, and influencer culture dominate public discourse. The masquerade continues—only now the steamboat is a livestream, and the con artist might be an algorithm.

Universities must grapple with this new epistemological crisis. What is truth in an age of synthetic media? What is scholarship when data itself can be manipulated?

In both 1857 and 2025, America faces a reckoning. Then, it was slavery and sectional violence. Now, it’s climate collapse, racial injustice, and the erosion of democratic norms. The question is not whether institutions will survive—but whether they can evolve.

Higher education must decide: Will it be a passive observer of decline, or an active agent of renewal?

Melville’s novel ends without resolution. The confidence man disappears into the crowd, leaving readers to wonder whether anyone aboard the steamboat was ever truly honest. In 2025, we face a similar uncertainty. The masquerade continues, and the stakes are higher than ever.

For higher education, the challenge is clear: to restore trust, to defend truth, and to prepare students not just for jobs—but for citizenship in an age of confidence games.

Amid rising political violence, the need for nonpartisan civic education has never been clearer. Yet saying, “civic thought” or “civic life and leadership” now reads conservative. Should it?

With the backing of a legislature his party dominated, Republican governor Doug Ducey created Arizona State University’s School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership in 2016. Both SCETL and its founding director, Paul Carrese, are now understood as key leaders in a movement for civic schools and centers.

In a March 2024 special issue on civic engagement in the journal Laws, Caresse outlines a deepening American civic crisis, including as evidence, “the persistent appeal of the demagogic former President Donald Trump.”

He’s not exactly carrying water for the MAGA movement.

Whether MAGA should be considered conservative is part of the puzzle. If by “conservative” we mean an effort to honor that which has come before us, to preserve that which is worth preserving and to take care when stepping forward, civic education has an inherently conservative lineage.

But even if we dig back more than a half century, it can be difficult to disentangle the preservation of ideals from the practices of partisanship. The Institute for Humane Studies was founded in the early 1960s to promote classical liberalism, including commitments to individual freedom and dignity, limited government, and the rule of law. It has been part of George Mason University since 1985, receiving millions from the Charles Koch Foundation.

Earlier this year, IHS president and CEO Emily Chamlee-Wright asserted that President Trump’s “tariff regime isn’t just economically harmful—it reverses the moral and political logic that made trade a foundation of the American experiment.” Rather than classifying that column through a partisan lens, we might consider a more expansive query: Is it historically accurate and analytically robust? Does it help readers understand intersections among the rule of law, individual freedom and dignity?

The editors at Persuasion, which ran the column, certainly would seem to think so. But Persuasion also has a bent toward “a free society,” “free speech” and “free inquiry,” and against “authoritarian populism.” The founder, Yascha Mounk, a political scientist at Johns Hopkins University, has been a persistent center-left critic of what he and others deem the excesses of the far left. Some of the challenges they enumerate made it into Steven Pinker’s May opinion piece in The New York Times, in which Pinker defended Harvard’s overwhelming contributions to global humanity while also admitting to instances of political narrowness; Pinker wrote that a poll of his colleagues “turned up many examples in which they felt political narrowness had skewed research in their specialties.” Has political narrowness manifested within the operating assumptions of the civic engagement movement?

Toward the beginning of this century, award-winning researchers Joel Westheimer and Joseph Kahne pushed for a social change–oriented civic education. Writing in 2004, in the American Educational Research Journal, they described their predispositions as such: “We find the exclusive emphasis on personally responsible citizenship when estranged from analysis of social, political, and economic contexts … inadequate for advancing democracy. There is nothing inherently democratic about the traits of a personally responsible citizen … From our perspective, traits associated with participatory and justice oriented citizens, on the other hand, are essential.”

Other scholars have also pointed to change as an essential goal of civic education. In 1999, Thomas Deans provided an overview of the field of service learning and civic engagement. He noted dueling influences of John Dewey and Paulo Freire across the field, writing, “They overlap on several key characteristics essential to any philosophy of service-learning,” including “an anti-foundationalist epistemology” and “an abiding hope for social change through education combined with community action.”

Across significant portions of the fields of education, service learning and community engagement, the penchant toward civic education as social change had become dominant by 2012, when I inhabited an office next to Keith Morton at Providence College. It had been nearly 20 years since Morton completed an empirical study of different modes of community service—charity, project and social change—finding strengths and integrity within each. By the time we spoke, Morton observed that much of the field had come to (mis)interpret his study as suggesting a preference for social change over project or charity work.

While service learning and community engagement significantly embraced this progressive orientation, these pedagogies were also assumed to fulfill universities’ missional commitments to civic education. Yet the link between community-engaged learning and education for democracy was often left untheorized.

In 2022, Carol Geary Schneider, president emerita of the American Association of Colleges and Universities, cited real and compounding fractures in U.S. democracy. Shortly thereafter in the same op-ed, Geary Schneider wrote, “two decades of research on the most common civic learning pedagogy—community-based projects completed as part of a ‘service learning’ course—show that student participation in service learning: 1) correlates with increased completion, 2) enhances practical skills valued by employers and 3) builds students’ motivation to help solve public problems.”

All three of these outcomes are important, but to what end? The first serves university retention goals, the second supports student career prospects and the third contributes broadly to civic learning. Yet civic learning does not necessarily contribute to the knowledge, skills, attitudes and beliefs necessary to sustain American democracy.

There is nothing inherently democratic about a sea of empowered individuals, acting in pursuit of their separate conceptions of the good. All manner of people do this, sometimes in pursuit of building more inclusive communities, and other times to persecute one another. Democratic culture, norms, laws and policies channel energies toward ends that respect individual rights and liberties.

Democracy is not unrestrained freedom for all from all. It is institutional and cultural arrangements advancing individual opportunities for empowerment, tempered by an abiding respect for the dignity of other persons, grounded in the rule of law. Commitment to one another’s empowerment starts from that foundational assumption that all people are created equal. All other democratic rights and obligations flow from that well.

Proponents of civic schools and centers have wanted to see more connections to foundational democratic principles and the responsibilities inherent in stewarding an emergent, intentionally aspirational democratic legacy.

In a paper published by the American Enterprise Institute, Benjamin Storey and Jenna Silber Storey consider next steps for the movement advancing civic schools and centers, while also emphasizing responsibility-taking as part of democratic citizenship. They write, “By understanding our institutions of constitutional government, our characteristic political philosophy, and the history of American politics in practice as answers to the challenging, even paradoxical questions posed by the effort to govern ourselves, we enter into the perspective of responsibility—the citizen’s proper perspective as one who participates in sovereign oversight of, and takes responsibility for, the American political project. The achievement of such a perspective is the first object of civic education proper to the university.”

This sounds familiar. During the Obama administration, the Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement National Task Force called for the “cultivation of foundational knowledge about fundamental principles and debates about democracy.” More than a half century before, the Truman Commission’s report on “Higher Education for American Democracy” declared, “In the past our colleges have perhaps taken it for granted that education for democratic living could be left to courses in history and political science. It should become instead a primary aim of all classroom teaching and, more important still, of every phase of campus life.” And in the era of the U.S. founding, expanding access to quality education was understood as central to the national, liberatory project of establishing and sustaining democratic self-government. Where does this leave us today?

Based on more than 20 years of research, teaching and administration centered around civic education, at institutions ranging from community colleges to the Ivy League, I have six recommendations for democratic analysis, education and action to move beyond this hyperpartisan moment.

This essay, it must be noted, was almost entirely completed before the political assassination of Charlie Kirk. It now becomes even clearer that we must identify ways to analyze beyond partisan pieties while embracing human dignity. Some leaders are reminding us of our ideals. Utah governor Spencer Cox’s nine minutes on ending political violence deserves a listen. Ezra Klein opened his podcast with a reflection on the meaning of the assassination, followed by his characteristic modeling of principled disagreement with a political opponent (in this case, Ben Shapiro). It is the second feature of that Klein podcast—extended periods of exploration, disagreement and brief periods of consensus regarding critical democratic questions—that we must see more of across campuses and communities. One of the worst possible, and unfortunately plausible, outcomes of this movement for civic schools and centers could be the continuing balkanization of campuses into self-sorted identity-based communities, with very little cross-pollination. That would be bad for learning and for our country.

Whatever the political disposition of civic centers or other programs across campus, we need more and better cross-campus commitment to democratic knowledge, values and beliefs if we wish to continue and strengthen the American democratic tradition.

The high cost associated with college is one of the greatest deterrents for students interested in higher education. A 2024 survey by Inside Higher Ed and Generation Lab found that 68 percent of students believe higher ed institutions charge too much for an undergraduate degree, and an additional 41 percent believe their institution has a sticker price that’s too high.

A recent study by the National College Attainment Network found that a majority of two- and four-year colleges cost more than the average student can pay, sometimes by as much as $8,000 a year. The report advocates for additional state and federal financial aid to close affordability gaps and ensure opportunities for low- and middle-income students to engage in higher education.

Methodology: NCAN’s formula for affordability compares total cost of attendance (tuition, fees, housing, etc.) plus an emergency reserve of $300 against any aid a student receives. This includes grants, federal loans and work-study dollars, as well as expected family contribution and the summer wages a student could earn in a full-time, minimum-wage job in their state. Housing costs vary depending on the student’s enrollment: Bachelor’s-granting institutions include on-campus housing costs, and community colleges include off-campus housing rates.

National College Attainment Network

Costs that outweigh expected aid and income are classified as an “affordability gap” for students.

A recent Inside Higher Ed and Generation Lab survey of 5,065 undergraduates found that 9 percent of respondents said an unexpected expense of $300 or less would threaten their ability to remain enrolled in college.

The total sample size covered 1,137 public institutions, 600 of which were community colleges.

Majority of colleges unaffordable: Using these metrics, 48 percent of community colleges and 35 percent of bachelor’s-granting institutions were affordable during the 2022–23 academic year. In total, NCAN rated 473 institutions as affordable.

Comparative data from 2015–16 finds slightly more community colleges were affordable then (50 percent) than in 2022–23 (48 percent), but that the average affordability gap, or total unmet need, has grown from $246 to $486.

Among four-year colleges, more public institutions were affordable in 2022–23 than in 2015–16 (29 percent) and the average affordability gap shrank slightly, from $1,656 to $1,554. The data indicates slight improvement in affordability metrics but highlights challenges for low-income students interested in a bachelor’s degree, according to the report.

NCAN researchers believe the $400 increase in the maximum Pell Grant in 2023 helped lower costs per student at bachelor’s-granting institutions, but community colleges appear less affordable due to the loss of HEERF funding and the increase in cost of attendance due to rising housing costs.

Affordability ranges by states: Access to affordable institutions is also more of a challenge for students in some regions than in others. NCAN’s analysis found that 14 states lacked a single institution with an affordable bachelor’s degree program for low-income students. In 27 states, 65 percent of public four-year colleges were unaffordable.

For two-year programs, five states lacked an affordable community college. Some states had a small sample (fewer than five) of community colleges analyzed; Delaware and Florida had no community colleges in NCAN’s sample.

In Kentucky, Maine and New Mexico, 100 percent of the two-year colleges analyzed were found to be affordable for students, along with at least 80 percent of the bachelor’s degree–granting institutions in those states.

Students pursuing a bachelor’s degree in New Hampshire ($8,239), Pennsylvania ($8,076) and Ohio ($5,138) had the largest affordability gaps. For community colleges, students in New Hampshire ($11,499), Utah ($7,689) and Pennsylvania ($4,508) had the greatest unmet need.

Conversely, some states had aid surpluses, which can help address other expenses associated with college, including textbooks and transportation.

Cost isn’t the only barrier to access, however. “For many students who live in rural or remote areas, far from the postsecondary institutions in their state, college may remain inaccessible,” the report noted.

Based on the data, NCAN supports additional funding for higher education at all levels, federal, state and local, to provide students with financial aid.

Get more content like this directly to your inbox. Subscribe here.