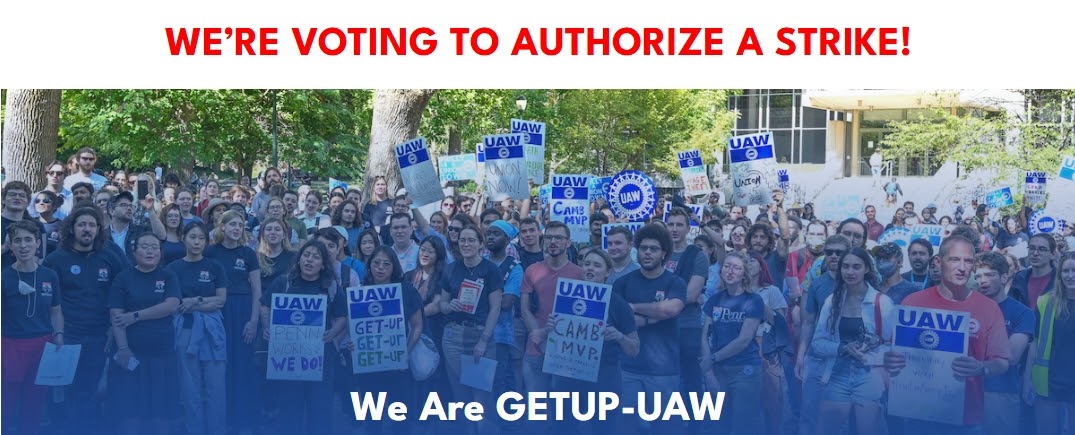

Graduate student workers at Penn have overwhelmingly authorized a strike — a decisive move in their fight for fair pay, stronger benefits, and comprehensive protections. The vote reflects not only deep frustration with stalled negotiations but also the growing momentum of graduate-worker organizing nationwide.

A year of bargaining — and growing frustration

Since winning union recognition in May 2024, GET‑UP has spent over a year negotiating with Penn administrators on their first collective-bargaining agreement. Despite 35 bargaining sessions and tentative agreements on several non-economic issues, key demands — especially around compensation, benefits, and protections for international students — remain unmet.

Many observers see the strike authorization as long overdue. “After repeated delays and insulting offers, this was the only way to signal our seriousness,” said a member of the bargaining committee. Support for the strike among graduate workers is overwhelmingly strong, reflecting a shared determination to secure livable wages and protections commensurate with the vital labor they provide.

Strike authorization: a powerful tool

From Nov. 18–20, GET‑UP conducted a secret-ballot vote open to roughly 3,400 eligible graduate employees. About two-thirds voted, and 92% of votes cast authorized a strike, giving the union discretion to halt academic work at a moment’s notice.

Striking graduate workers, many of whom serve as teaching or research assistants, would withhold all academic labor — including teaching, grading, and research — until a contract with acceptable terms is reached. Penn has drafted “continuity plans” for instruction in the event of a strike, which union organizers have criticized as strikebreaking.

Demands: beyond a stipend increase

GET‑UP’s contract demands include:

-

A living wage for graduate workers

-

Expanded benefits: health, vision, dental, dependent coverage

-

Childcare support and retirement contributions

-

Protections for international and immigrant students

-

Strong anti-discrimination, harassment, and inclusive-pronoun / gender-neutral restroom protections

While Penn has agreed to some non-economic protections, many critical provisions remain unresolved. The stakes are high: graduate workers form the backbone of research and teaching at the university, yet many struggle to survive on modest stipends.

Context: a national wave of UAW wins

Penn’s graduate workers are part of a broader wave of successful organizing by the United Auto Workers (UAW) and allied graduate unions. Recent years have seen UAW-affiliated graduate-worker locals achieve significant victories at institutions including Cornell, Columbia, Harvard, Northwestern, and across the University of California (UC) system.

At UC, a massive systemwide strike in 2022–2023 involving tens of thousands of Graduate Student Researchers (GSRs) and Academic Student Employees (ASEs) secured three-year contracts with major gains:

-

Wage increases of 55–80% over prior levels, establishing a livable baseline salary.

-

Expanded health and dependent coverage, childcare subsidies, paid family leave, and fee remission.

-

Stronger protections against harassment, improved disability accommodations, and support for international student workers.

-

Consolidation of bargaining units across ASEs and GSRs, strengthening long-term collective power.

These gains demonstrate that even large, resource-rich institutions can be compelled to recognize graduate labor as essential, and to provide fair compensation and protections. They also show that coordinated, determined action — including strike authorization — can yield significant, lasting change.

What’s next

With strike authorization in hand, GET‑UP holds a powerful bargaining tool. While a strike remains a last resort, the overwhelming support among members signals that the union is prepared to act decisively to secure a fair contract. The UC precedent, along with wins at other UAW graduate-worker locals, suggests that Penn could follow the same path, translating student-worker momentum into meaningful, tangible improvements.

The outcome could have major implications not just for Penn, but for graduate-worker organizing across the country — reinforcing that organized graduate labor is increasingly a central force in higher education.