This entry is also available via Inside Higher Ed in a format more amenable for sharing or printing.

~~~~~~~~~~

Post-EU Referendum turmoil in the UK (and the EU) continues, for all sorts of reasons, but soon more serious and sustained assessment of the post-Brexit landscape for UK universities will occur. This blog entry is an exercise in thinking future-forward, brainstorming-fashion (so all caveats apply!), about one possible risk-reducing option.

In such a context here is the question to consider: is an Oxbridge-Lille (a joint Cambridge-Oxford university) or equivalent (e.g., Imperial College-Lille; Birmingham-Nottingham-Warwick-Lille) campus in the Eurostar hub city of Lille an institutional-organizational level option to reduce risk and ensure stable access to EU nationals (including staff and students), creative UK staff with EU citizenship dreams (for themselves, and their children should they have any), EU research monies, EU-funded research infrastructures, and relevant EU policy-making fora and bodies? Or might the Euro-UK equivalent of Singapore’s Campus for Research Excellence and Technological Enterprise (CREATE), in a similar location, be a creative post-Brexit option? Or might an equivalent of Cornell Tech NYC be worth creating in European higher education and research space?

In other words, is it time for the UK university-territory relationship to be reconsidered, or at least debated, vs simply waiting and seeing what might emerge over the next 2-4 years via the ‘leadership’ of Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson, et al?

Context

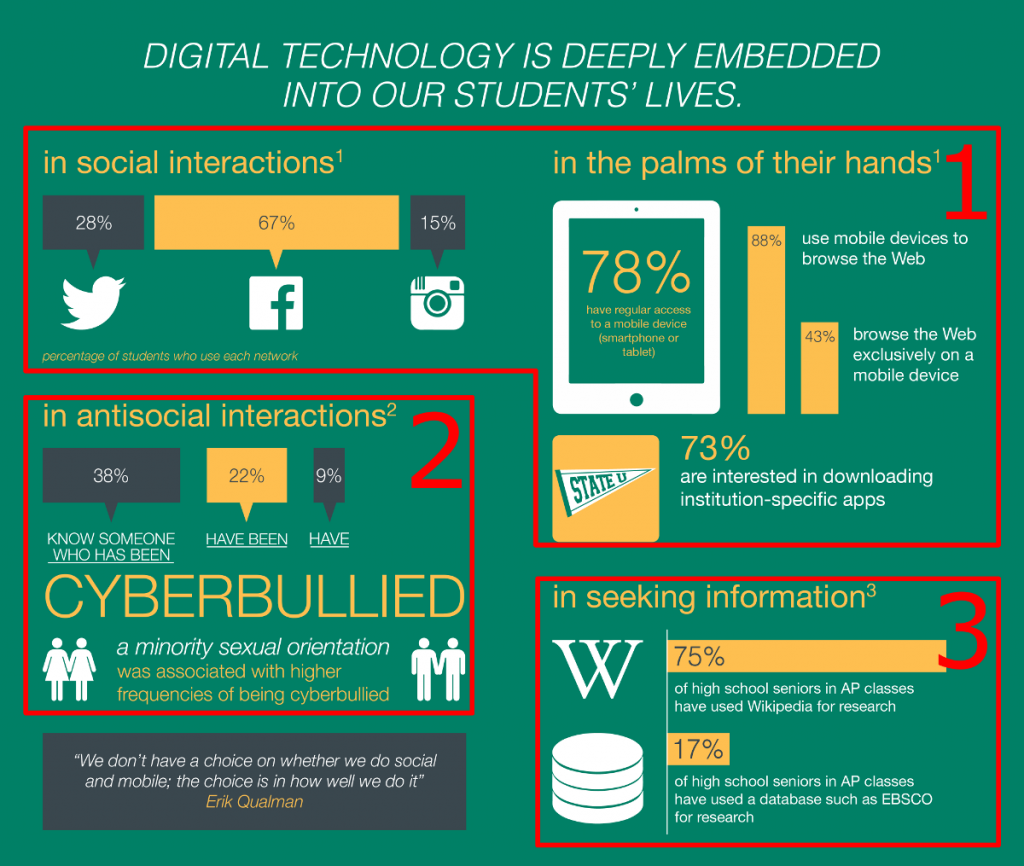

The implications of ‘Brexit’ for UK universities are many, hence their leaderships’ unified argument and vigorous engagement in the pre-EU Referendum campaign. We heard, for example, about the over-dependence of UK universities upon EU students and staff, and the critical role of EU research monies (especially via Horizon 2020 and the European Research Council) in supporting one of the most research-active higher education systems in the world.

A glance at any of the backgrounders below makes a patently obvious point – the UK is deeply integrated into the European Union, the European Research Area (ERA) and the European Higher Education Research Area (EHEA), both formally and informally:

- The Implications of International Research Collaboration for UK Universities: research assessment, knowledge capacity and the knowledge economy (J. Adams & K..A. Gurney, February 2016)

- International Higher Education in Facts and Figures 2016 (International Unit, Universities UK, 2 June 2016)

- University EU research funding gives £1bn boost to economy and creates jobs (Universities UK, 10 June 2016)

- Economic impact on the UK of EU research funding to UK universities (Universities UK, 10 June 2016)

- UK research and the European Union (Royal Society, 17 June 2016)

- Over exposed: where are the EU students? (Wonk HE, 26 June 2016)

- The Implications of the EU Referendum for UK Social Science (Academy of Social Sciences, June 2016)

- EU Referendum – Leave: What next for UK social science (Academy of Social Sciences Campaign for Social Science, 24 June 2016)

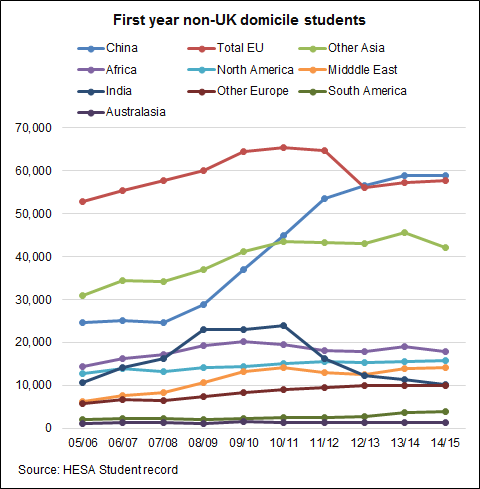

For example 46,230 postgraduate students and 78,435 undergraduates originating from the European Union (excluding the UK) studied in the UK in 2014-15 according to WonkHE, making up 5.5% of the total student population. This is a significant and relatively stable stream of non-UK students at the undergraduate level, as is evident in this figure from the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA):

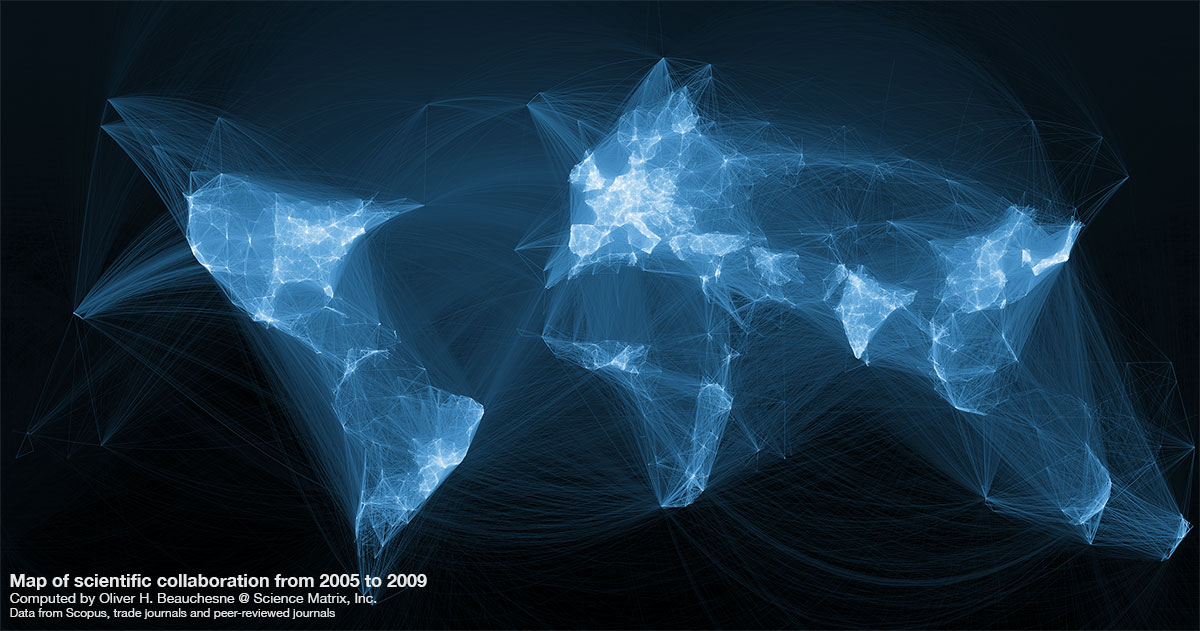

Needless to say, UK university-based researchers also participate in numerous research consortia coordinated out of continental European universities, as well as exercise leadership at multiple scales in the EU-supported research and teaching policies, programs and projects.

Given that service exports (including education) generate localized expenditures (e.g., housing, food, entertainment) expenditures related to students from non-UK EU countries in the UK was estimated to “generate £3.7 billion for the UK economy and support over 34,000 British jobs.” All in all, the UK is an overall beneficiary when it comes to EU-related research money and EU-sourced or supported student and staff mobility. And this does not even begin to factor in the positive intellectual impacts of enhanced cooperation between UK and other EU universities, a phenomenon discussed in some detail by the Royal Society in 2016, and very much evident to US-based collaborations like myself.

Brexit, Transition Politics, & Risk

It is no exaggeration to state that the Leave win in the EU Referendum was a shock to most stakeholders associated with the higher education community in the UK, in other EU nations, and in regional associations (e.g., the European Students’ Union; the European University Association; League of European Research Universities). In short order, major expressions of discontent and concern were expressed in the UK by university associations, individual university leaders, the higher education media (especially Times Higher Education), and individual staff and students. Concerns emerged about the potential loss of research monies (a prediction apparently being brought to life already due to the marginalization of UK researchers from project proposal consortia), the ability of UK universities to guarantee right of residency for the many EU staff they depend upon; difficulties in student recruitment, access to or possible relocation of EU research infrastructures (broadly defined), and the unleashing of xenophobia that has made many non-UK European researchers and students feel discriminated against and unwelcome. On the last point, part of the issue is that non-UK EU nationals are being effectively being told, via coded language, that they are bargaining chips in what will be multi-year UK-EU negotiations about the human mobility and the free movement of workers.

More broadly, Science and Technology Committee chair Nicola Blackwood told Science Minister Jo Johnson this week: ‘I think this [Brexit] will be make or break for our knowledge economy.’ More specifically, Blackwood said:

Can I … plead with you to make the case within Government, not only that issues such as continued access to Horizon 2020 [a funding scheme] are maintained and collaboration [is maintained] and the right kind of immigration system that benefits our science and higher education sectors are in place, but also that the science and innovation community is at the heart of the exit negotiations, as you’ve been saying is important, because I think this will be make or break for our knowledge economy going forward.

Blackwood raises an important issue, for in a multi-year period of tumultuous change coming up, all subject to political machinations, just how important of a priority will universities be in the big picture? This is a point Martin McQuillan also raised just prior to the referendum vote when he stated:

The chaos created in the intervening years by the gravitational pull of the right wing of the Conservative Party and their UKIP allies will be the legacy of the Cameron and Osborne governments. It is unlikely to be an environment in which our universities will flourish.

The governmental context shifted today, too, for UK “universities are on the move to the Department for Education” from the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS) which is itself being refashioned into the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (where research matters will be managed in the future). As Mark Leach of WonkHE put it:

Breaking up the family like this will be unpopular with vice chancellors who will now need to lobby two departments on overlapping issues. It also separates universities from the department with responsibility for infrastructure, growth and industry and takes HE policy further away from the industrial policy ‘action’ at home, and limits universities to some of the exposure to Britain’s international trade links that BIS used to pursue.

On the Future of UK universities in a Post-Brexit World

What will be the future of UK universities in a post-Brexit world? Will they all (or the vast majority of them) wait and see what emerges from the negotiations, focusing their lobbying efforts on strategic units, politicians, and officials? Perhaps. There is plenty of uncertainty to factor in, though, as Nick Hillman (Director, The Higher Education Policy Institute) put it in a 5 July 2016 speech to the University of Nottingham’s executive board:

No one knows what is going to happen for certain, so we can argue and act in favour of the future we desire. We can, to coin a phrase, take back control of the argument… We are only now coming to think about all the questions and not all the possible answers are obvious.”

In this section, I’d like to suggest that UK universities take seriously the words of Jo Johnson (Minister of State for Universities and Science) on 13 July 2016 when he stated:

Brexit does not mean that we are becoming insular and inward-looking in any way, but, on the contrary, we are going to be more outward-looking, more open and more globally minded than ever before.

but in a manner that builds upon global regionalisms (including the development of the ERA & the EHEA) that have helped enable the creation of a more resilient and outward-looking higher UK educational and research system over the last decade plus.

Could an ‘outward-looking’ UK university deal with Brexit-related risk, take advantage of progress in developing the EHEA and the ERA, and contribute to refashioning its future structure and identity by creating a new and deeply embedded campus in a nearby (commuting time-wise) Eurostar station city like Lille, France, safely in EU-space? Commercial presence in the EU, to use GATS parlance, would enable a multi-campus model to emerge like the one visualized in the bottom of the figure below.

Models for the Globalization of Higher Education

Source: based on Hawawini, G. (2011) The Internationalization of Higher Education Institutions: A Critical Review and a Radical Proposal (November 2011).

In such a model, students and faculty regularly travel between campuses; indeed programs tend to be designed such that components are held in multiple locations. The nodal location also enables the university to leverage these flows. This model is not one associated the creation of offices or small outreach campuses where teaching occurs, with minimal basic research; rather, these campuses broadly replicate the terms and conditions of faculty and staff in the main (origin) campus. Indeed the replication of such employment conditions is required in some contexts (e.g., Singapore) where state largesse, subject to contractual agreements, facilitates the new campus development process.

Campus View from West Loop Road. The Bloomberg Center, Residential Building, The Bridge (listed from left to right) – Credit Kilograph, Weiss Manfredi, and Handel Architects

Other models also exist, including the Euro-UK equivalent of Singapore’s Campus for Research Excellence and Technological Enterprise (CREATE), an option several of us from US universities (including UW-Madison, MIT, Georgia Tech, Texas A&M, Carnegie Mellon) recently discussed at a workshop on International University Research Ventures: Implications for US Economic Competitiveness and National Security. Most international research university ventures are STEM-related, though given what’s happening in Europe and the broader region, a case could certainly be made for an innovative UK-EU-Other campus that focuses on global challenges/problems including terrorism, climate change, financialization, refugee crises, risk/uncertainty, and the like. In short, an Oxbridge-Lille (or equivalent) campus is in the realm of the possible, potentially leading to educational innovation within the UK and EU irrespective of what Boris and Her Majesty’s Principal Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union (David Davis) are able to pull off over the next 2-6 years.

In Conclusion

I was in Copenhagen the week before the EU Referendum vote was held participating in a UNIKE conference regarding University Futures. This event, as well as the EU-funded project it is an outcome of, is an excellent of what UK university engagement in EU research and professional development programming can engender. The network structure of the project brought together UK, continental European, and European Higher Education Area-scale faculty, (post)graduate students , postdocs, and staff to explore various dimensions of universities and the knowledge-based economy. The network also extended into Asia and North America. Compared to many North American events focused on similar topics, this was a relatively cosmopolitan gathering; a sign of how 21st century regionalisms are indeed open regionalisms; they are not closed and inward looking, but instead use the phenomenon of global regionalism to build up capacity of constituent parts to engage globally.

As Anne Corbett recently stated in University World News:

It is not going to be an easy time for higher education. Nothing can be the same. But as the UK higher education world reflects on how it is to continue on the post-Brexit path, it is surely time to take a deep breath and return to fight with renewed energy for the values of European cooperation, as well as the money that has come into the sector from the EU.

In this entry I am arguing UK universities might want to rethink their territorial relationship(s) and consider options for becoming more deeply embedded in EU-space in preparation for a post-Brexit non-EU world. And in doing so UK universities might help stabilize and hopefully further not only their own institutional-organizational development futures, but also contribute to the development of the Europe educational and research space they are unquestionably dependent upon.

There are, no doubt, dozens of challenges (many legal) for why the ideas put forward above might be enormously difficult if not impossible to operationalize, though they’re posed here in the context of recognition that, as Nick Hillman put it last week, “not all the possible answers are obvious.”

Kris Olds (with thanks for input on this topic from numerous colleagues in Belgium, the UK & the USA)