Artificial Intelligence is reshaping how school administrators, from K–12 principals to university registrars, manage operations, make decisions, and communicate with stakeholders. As resources tighten and expectations rise, AI tools for school administrators offer a powerful opportunity to do more with less. In the 2023–24 school year, a growing majority of K–12 staff are now using AI tools in their work. In a recent Ellucian survey, 61% of higher ed respondents said they’re already using AI, and about 80% cited productivity and efficiency as their main reasons for adopting it.

This isn’t just a tech trend. It’s a real shift in how schools function. AI can automate repetitive tasks, surface data-driven insights, and generate personalized communications. For busy administrators, that means less time on paperwork and more time supporting students and staff.

In this article, we’ll break down how AI is transforming educational management. You’ll see practical use cases, benefits like faster decision-making and streamlined workflows, and what to watch out for when it comes to ethics and implementation. Whether you’re running a district office or managing a registrar’s team, this guide will help you lead smarter and work more efficiently, with AI as your partner.

How AI Enhances Decision-Making for Administrators

How does AI help school administrators make better decisions? AI’s greatest strength in school management lies in transforming raw data into clear, actionable insights. Administrators regularly face overwhelming volumes of information, grades, attendance, budget reports, and surveys that can be difficult to parse manually. AI tools help by quickly identifying patterns that support evidence-based decisions.

Predictive analytics, for example, can forecast enrollment trends or flag early warning signs. A high school principal might spot which student groups are at risk of chronic absenteeism, while a registrar could project staffing needs for upcoming semesters based on historical data.

AI dashboards make this analysis easy to interpret. They can highlight underused programs, suggest reallocating resources, or model different outcomes to support strategic planning. If an extracurricular activity shows consistently low participation, the system might recommend shifting resources to better-performing initiatives.

The result is faster, more informed decision-making. With AI as a planning partner, administrators gain a sharper view of their institution and can act with confidence and precision.

Automating Routine Administrative Tasks with AI

What routine administrative tasks can AI automate in schools? From attendance logs to class schedules, school administrators are buried in repetitive tasks that sap time and focus. AI is stepping in to take care of the busywork, streamlining operations and giving staff space to lead more strategically.

Take attendance tracking. Instead of manual entry, AI-powered systems can log student presence through smart ID cards or facial recognition check-ins. These tools don’t just record absences; they spot trends. A sudden drop in attendance? The system flags it, prompting early intervention. Some schools now pair attendance with performance data to identify at-risk students before grades slip or disengagement deepens.

Scheduling is another pain point. Building a timetable involves balancing staff availability, room assignments, student choices, and course caps. AI algorithms solve this puzzle fast. In Boston, a genetic algorithm optimized school bus routes in under an hour, cutting 50 buses and saving $5 million annually. That same principle applies to class scheduling, resource allocation, and beyond.

Report generation also gets a boost. AI tools for school administrators can pull data and format it into accurate, ready-to-send reports, such as monthly summaries, performance dashboards, and compliance logs, without human input. Even tedious data entry tasks like processing forms or invoices are simplified through OCR-powered automation.

Need to review a long policy or school social media policy? AI tools now scan, summarize, and highlight what matters. Post-meeting? Transcription services like Otter.ai generate action items and summaries within minutes.

The impact is clear: by automating the everyday, AI frees up time for what truly matters, strategic thinking, collaboration, and student support.

AI for Communication and Writing in School Administration

Strong communication is central to effective school leadership. Yet writing everything from newsletters to policy updates can eat up an administrator’s already busy schedule. That’s where AI can step in, not to replace the human voice, but to support it.

Generative AI tools like Grammarly, ChatGPT, and Jasper are helping school leaders draft clearer, more consistent communications. Do you need to send a monthly update to parents? AI can suggest section headers, polish grammar, and help set the right tone. Drafting a memo to staff? AI can create a first version that administrators can refine for local context. These tools are especially helpful when writing in a non-native language or tailoring content to a specific reading level.

They also save time on summarizing. AI can distill a lengthy school board report into a concise briefing in seconds, or help craft sensitive messages with more precision. One district principal used AI to write a winter holiday letter. The tone was spot on, but the AI mistakenly referenced sledding, forgetting the school was in a warm climate. The principal simply edited it. This type of human oversight ensures accuracy while significantly reducing drafting time.

AI’s reach extends beyond written documents. Many schools and universities now use chatbots to handle FAQs around enrollment, deadlines, and policies. Georgia State’s “Pounce” chatbot reduced summer melt by 21 percent by keeping students engaged. CSUN’s “CSUNny” improved retention by providing 24/7 support. In K–12, chatbots answer parent questions or send automated reminders, freeing staff from phone call overload.

In short, AI acts as a communication partner, speeding up writing, strengthening clarity, and helping administrators stay connected without burning out.

Key Benefits of AI in School Management

When thoughtfully implemented, AI can significantly improve how schools are run, especially for administrators balancing limited resources, increasing demands, and time-sensitive responsibilities. Here are five key advantages that AI brings to school management.

Greater Efficiency and Time Savings

AI handles repetitive, time-consuming tasks such as data entry, attendance tracking, report generation, and scheduling. Automating these processes minimizes errors and frees up valuable hours for principals and support staff to focus on more impactful activities, like supporting teachers, engaging with parents, and driving instructional improvements. According to the McKinsey report, AI tools can help educators and administrators reclaim 20 to 40 percent of their time previously spent on routine tasks.

Cost Savings and Better Use of Resources

Schools often operate on tight budgets. AI helps by identifying operational inefficiencies and suggesting cost-saving alternatives. AI also helps in allocating resources more wisely, whether adjusting staffing based on predicted needs or identifying underutilized facilities to repurpose. These efficiencies help schools manage tight budgets. Schools can avoid unnecessary expenditures by relying on AI analysis to guide decisions.

Smarter, Data-Driven Decisions

AI systems analyze student performance, behaviour trends, and resource utilization far more quickly than a human could. For instance, if data shows that a particular grade level is struggling in math, school leaders can intervene early with targeted support. Having these insights readily available leads to stronger decisions grounded in real evidence.

Stronger, Personalized Communication

AI-powered tools like chatbots and automated messaging platforms allow schools to provide timely, personalized updates to parents and students. From attendance alerts to event reminders, these systems ensure important information gets delivered and acted on, without staff needing to make dozens of phone calls or send multiple emails.

Strategic Focus and Innovation

By handling operational tasks in the background, AI gives administrators more bandwidth to focus on long-term priorities. Whether that’s improving school culture, mentoring educators, or piloting new programs, leaders can spend less time buried in paperwork and more time driving change.

Challenges of Implementing AI for School Administrators

What challenges do schools face when implementing AI tools? The potential of AI in education is vast, but unlocking it requires more than just installing a new tool. For school administrators, adopting AI often brings a mix of excitement and logistical complexity. Here are the key implementation challenges leaders should be prepared to navigate.

Upfront Costs and Infrastructure Needs

Launching AI systems can involve steep initial costs. Schools may need to purchase licenses, upgrade hardware, or improve network connectivity. Basic requirements like reliable internet and compatible devices can be hurdles, especially in underfunded or rural districts. While grants or partnerships may offset expenses, planning for these investments is essential.

Staff Training and Resistance to Change

AI adoption means changes in workflows. Teachers, clerical staff, and leadership teams must learn how to use new tools effectively. Resistance often stems from fear of job displacement or lack of familiarity. Providing professional development, starting with small pilots, and showing quick wins are all important steps in gaining staff buy-in.

Data Integration and Quality Issues

AI is only as good as the data it works with. Many schools operate with siloed or inconsistent data systems. AI needs clean, well-integrated data to function properly. If attendance, grades, or behaviour logs aren’t standardized, outputs can be skewed or misleading. Administrators may need to revamp data practices and work closely with IT teams to ensure accuracy and consistency.

Ongoing Maintenance and Oversight

AI tools aren’t set-it-and-forget-it. They require regular updates, monitoring, and occasional recalibration. Schools without dedicated IT support may struggle to sustain them. Assigning responsibility for AI upkeep and budgeting for long-term maintenance are key to success.

Human Trust and Role Clarity

Some staff may worry that automation threatens their jobs. Others may be skeptical of the AI’s accuracy. Administrators should communicate clearly that AI augments human work, not replaces it, and maintain human oversight to ensure outputs are reviewed and contextualized.

Addressing these challenges proactively can turn early hurdles into long-term advantages.

Ethical and Privacy Considerations with AI in Schools

Alongside technical and logistical challenges, school administrators must carefully consider the ethical implications of using AI. Because education involves minors and sensitive data, ethical missteps can have lasting consequences. From student privacy to algorithmic bias, it’s essential to put safeguards in place that prioritize safety, equity, and transparency.

Data Privacy and Security

AI systems often require access to student records, health information, and sometimes even biometric data. Feeding this information into cloud-based tools or algorithms increases the risk of misuse or breaches. Administrators must ensure that all systems meet rigorous data protection standards, and that families are informed about what data is collected and how it’s used. Best practices include strong encryption, regular audits, transparent data policies, and opt-out or deletion options when appropriate. Over-surveillance, like constant monitoring or facial recognition, can also undermine trust. Schools must strike a balance between data-driven insights and preserving a respectful learning environment.

Bias and Fairness

AI systems trained on historical data can unintentionally reinforce existing inequalities. Predictive models used to identify at-risk students, allocate resources, or evaluate staff must be tested for fairness across race, gender, and socioeconomic status. If unchecked, biased outputs could deepen disparities instead of correcting them. Administrators should work with vendors to ensure diverse training data and conduct regular audits of AI decisions. Involving stakeholders, teachers, parents, and even students in reviewing AI use helps bring community accountability into the process.

Transparency and Accountability

Schools should avoid “black box” tools that make recommendations without clear reasoning. Any AI system used to inform decisions, like admissions or discipline, should offer interpretable outputs and allow for human oversight. Clear policies must be in place to define who is responsible if the AI makes a mistake. Human judgment should always remain central.

Academic Integrity and Human Development

Generative AI tools raise new questions about cheating, originality, and learning. Administrators must set clear guidelines on acceptable and unacceptable use, emphasizing that AI should support learning, not replace it. Over-reliance on AI for writing or problem-solving can weaken essential student skills. Responsible use requires balancing innovation with the core educational mission of developing thinkers and communicators.

Equity of Access

AI should not become a new driver of inequality. If only well-funded schools can afford effective AI tools, achievement gaps will widen. Public institutions, nonprofits, and policymakers must work together to promote equitable access through shared resources, training, and support. Every student deserves the benefits of smart technology, not just those in the most resourced districts.

In short, the power of AI for school management must be matched with principled leadership. Ethical implementation demands vigilance, humility, and transparency, qualities that define the best

How to Implement AI in School Administration

Bringing AI into school administration is a strategic process, not a quick plug-and-play solution. To maximize its benefits and minimize disruption, education leaders need to approach AI adoption methodically. Here’s a roadmap for successfully implementing AI in school operations.

- Assess Needs and Define Goals

Start with a clear-eyed look at current workflows. What drains staff time? Where are inefficiencies or bottlenecks? Pinpoint specific areas where AI could make a meaningful difference, such as automating repetitive data entry or improving enrollment forecasting. From there, define measurable goals, like reducing schedule conflicts or increasing the speed of report generation. These targets will shape your entire implementation and help evaluate success.

Example: Katy Independent School District (Texas, USA): Facing a growing administrative burden, Katy ISD recognized that its support staff were “outnumbered” by high volumes of repetitive tasks (answering routine inquiries, data entry, etc.). District leaders set a concrete goal for their AI initiative: have AI handle roughly 30% of routine administrative inquiries – with 24/7, bilingual support – so that human staff can focus on high-value interactions. This target was born from a needs assessment of where staff time was being drained. By defining this goal (30% automation of inquiries), Katy ISD created a clear metric for success and a focused vision: use AI as a virtual assistant to improve responsiveness to families while freeing staff for more complex student and parent needs.

Source: Community Impact

- Research and Select the Right Tools

Not all AI tools are created equal. Once you’ve identified priorities, explore tools designed for education. Look for platforms that integrate easily with your existing systems (SIS, LMS, HR) and are user-friendly for staff. Prioritize solutions with strong vendor support and a track record in the education sector. Talking to peer institutions or reviewing relevant case studies can offer valuable insights.

Example: University of Richmond (Virginia, USA): In higher education, institutions are also methodical in choosing AI for administrative use. The University of Richmond explicitly notes the “transformative potential of generative AI…in enhancing administrative efficiencies”, but pairs that excitement with careful evaluation criteria. In official staff guidelines, the university directs its administrative teams to critically vet AI tools for technical fit, security, and ethical considerations. Staff are encouraged to pilot new AI-based services (from chatbots to transcription tools) in a controlled manner – checking that any chosen tool aligns with data privacy policies and the university’s values.

Source: University of Richmond

- Start with a Pilot

Choose a small-scale pilot to test your chosen tool. This might mean introducing a scheduling AI in one department or using a chatbot for financial aid inquiries. Track outcomes closely—are tasks being completed faster? Are users more satisfied? Gather feedback and refine the approach before expanding. A strong pilot builds confidence and creates internal champions.

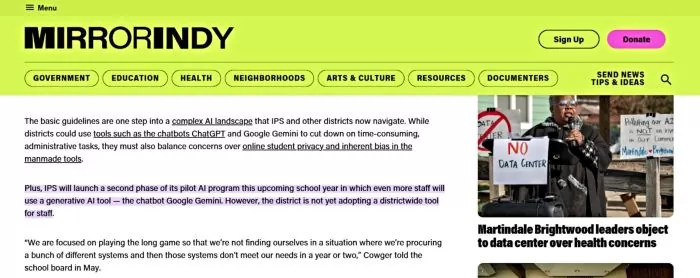

Example: Indianapolis Public Schools (Indiana, USA): IPS illustrates the wisdom of beginning AI adoption on a small scale. In the first year of its AI initiative, the district ran a pilot with just 20 staff members using a district-approved AI tool to handle some of their tasks. This limited pilot let IPS observe real-world uses and challenges (e.g., how an AI writing assistant might help draft reports) without impacting all schools. District leaders gathered feedback and saw improvements, which informed an official AI policy in development. This phased pilot approach gave IPS the chance to refine guidelines and train users in between phases.

Source: MirrorIndy

- Train Staff and Build Buy-In

Training is critical. Provide hands-on sessions, user guides, and a forum for questions. Explain how the AI will support, not replace, staff, and share early successes. Framing AI as a helpful assistant rather than a threat makes adoption smoother. Emphasize the time-saving potential and how it frees up staff for more meaningful work.

Example: School District of Philadelphia (Pennsylvania, USA): Philadelphia’s public school system, in partnership with the University of Pennsylvania, launched a first-of-its-kind AI training pilot to ensure educators and administrators were on board and prepared. The program, called PASS (Pioneering AI in School Systems), was announced in late 2024 and offers multi-tiered professional development free to a pilot group of district staff. Crucially, PASS explicitly targets mindset and skill-building: it trains district administrators on strategic planning for AI, guides school leaders on implementing AI tools in their schools, and coaches teachers on using AI to enhance (not replace) instruction.

Source: Penn GSE

- Scale Gradually and Integrate Thoughtfully

With a successful pilot in hand, plan for phased implementation. Avoid overwhelming staff by rolling out AI features in stages: first attendance, then scheduling, then reporting. Make sure each step integrates well with existing workflows. Be prepared to revise outdated processes to accommodate the new tool, and keep communication open throughout the transition.

Example: Indianapolis Public Schools (Indiana, USA): After its initial small-scale pilot, IPS is deliberately not rushing into a district-wide rollout – exemplifying thoughtful integration. The district is entering a second pilot year with more staff and a new tool (Google’s Gemini chatbot), but has held off on immediately procuring a permanent, system-wide AI platform. This restraint is intentional: IPS leaders want to ensure any AI tool is truly effective and fits their needs before integrating it into all schools. They are also developing an AI Advisory Committee (including administrators, teachers, tech, and legal experts) to guide integration and update usage policies as the pilot expands. By scaling usage gradually – first 20 staff, now a larger cohort, still not yet student-facing – IPS can adjust its data integration, security settings, and training materials in parallel.

Source: MirrorIndy

- Monitor, Measure, Improve

Implementation doesn’t stop at rollout. Regularly assess whether the AI is meeting your goals. Track KPIs like time saved, error rates, or satisfaction levels. Use this data to fine-tune the system and report outcomes to stakeholders. AI platforms often improve with use, especially those built on machine learning. Feeding back your school’s data will make them more effective over time.

Example: Deakin University (Victoria, Australia): Deakin’s IT and administrative teams exemplify continuous improvement with their AI-powered student services. The university’s digital assistant “Genie” was rolled out in stages and is closely monitored for usage and performance. Since launching across campus, Genie’s user base has more than doubled within a year over 25,000 students having downloaded the app, a metric the university tracks to gauge adoption. Deakin’s Chief Digital Officer noted they analyze conversation data: at peak times, Genie handles up to 12,000 conversations a day, and they review the top categories of student questions (e.g., timetable info, assignment deadlines). By identifying the most common inquiries, the team continuously updates Genie’s responses and adds new features. This ongoing measurement extends to quality checks – the university monitors whether Genie’s answers resolved students’ issues or if human staff had to follow up, informing further training of the AI.

Source: Deakin University

- Foster a Culture of Innovation

Successful AI integration requires a mindset shift. Leaders should create an environment where staff feel empowered to try new approaches and share feedback. Celebrate wins, learn from setbacks, and reinforce that AI is a tool to enhance human capacity, not replace it.

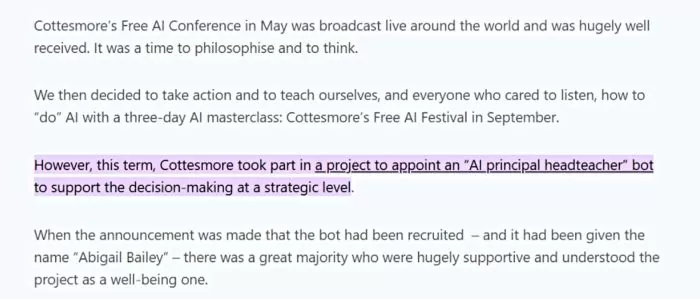

Example: Cottesmore School (West Sussex, UK): This independent boarding school has embraced an innovation-first culture in its administration, particularly with AI. Headmaster Tom Rogerson gained international attention in 2023 for appointing an AI chatbot as an “assistant headteacher” – named “Abigail Bailey” – to support strategic decision-making. The move was less about the tech itself and more about signaling to staff and students that experimenting with new ideas is welcome. Rogerson frames the project as a well-being and innovation initiative: the AI assistant serves as a “strategic leadership mentor,” providing impartial insights, while human leaders remain in charge. In addition to this high-profile experiment, Cottesmore has hosted free AI conferences and masterclasses for educators. For example, the school ran an “AI Festival” where staff from Cottesmore and other schools tried out AI tools and shared ideas in a collaborative environment. By openly discussing both the opportunities and challenges of AI, and even inviting outside experts to weigh in, the headmaster created a safe space for his team to be curious and creative.

Source: School Management Plus

Implementing AI in school administration is an ongoing journey, but with a clear strategy and commitment to collaboration, schools can unlock new levels of efficiency, insight, and impact. The result is a smarter, more responsive administrative operation that supports the broader mission of education.

Final Thoughts

AI is transforming education management by enhancing, not replacing, the work of school administrators. It takes on time-consuming tasks, delivers faster insights from data, and strengthens communication with students, families, and staff. The result is more time for leaders to focus on strategy, mentorship, and school culture.

At HEM, we view AI as a vital part of a modern, responsive education strategy. Schools that adopt AI thoughtfully are better prepared to navigate enrollment shifts, budget pressures, and rising expectations. The key is clear planning, ethical use, and keeping people at the centre.

AI gives administrators the support they need to lead more effectively. With the right approach, it can elevate the quality and impact of school leadership.

Frequently Asked Questions

Question: How does AI help school administrators make better decisions?

Answer: AI’s greatest strength in school management lies in transforming raw data into clear, actionable insights. Administrators regularly face overwhelming volumes of information, grades, attendance, budget reports, and surveys that can be difficult to parse manually. AI tools help by quickly identifying patterns that support evidence-based decisions.

Question: What routine administrative tasks can AI automate in schools?

Answer: From attendance logs to class schedules, school administrators are buried in repetitive tasks that sap time and focus. AI is stepping in to take care of the busywork, streamlining operations and giving staff space to lead more strategically.

Question: What challenges do schools face when implementing AI tools?

Answer: The potential of AI in education is vast, but unlocking it requires more than just installing a new tool. For school administrators, adopting AI often brings a mix of excitement and logistical complexity.