As the £4.3 million National Civic Impact Accelerator (NCIA) programme draws to a close in December, universities across the country are grappling with a fundamental question: what does sustainable civic engagement actually look like?

After three years of momentum building and collective learning, I find myself observing the sector at a crossroads that feels both familiar and entirely new. The timing feels both urgent and opportune.

The government’s renewed emphasis about universities’ civic role – most notably through Bridget Phillipson’s explicit call for institutions to “play a greater civic role in their communities” – creates opportunity and expectation. Yet this arrives at a challenging time for universities, with 43 per cent of England’s institutions facing deficits this year.

Despite this supportive policy context, I still find myself having conversations like, “but what exactly is civic?”, “is civic the right word?” or – most worryingly – “we can’t afford this anymore.”

As universities face their most challenging financial circumstances in decades, we need to be bolder, clearer, and more precise about demonstrating our value to places and communities, across everything we do.

Determination

Instead of treating place-responsive work as a competition on some imagined league table or trying to redefine the term to fit the status quo, we need to come together to demonstrate our value to society collectively. But perhaps most importantly, we need to commit to reflect and do better despite the financial challenges.

This isn’t about pinning down a narrow, one-size-fits-all definition and enforcing uniformity. Instead, it’s about recognising and valuing the diversity of place-responsive approaches seen across the country. From the University of Kent’s Right to Food programme to Anglia Ruskin University’s co-creation approach to voluntary student social impact projects. From Dundee’s Art at the Start project to support infant mental health and address inequalities, to how Birmingham City University is supporting local achievement of net-zero ambitions through their climate literacy bootcamps.

Sometimes, it means making tough choices to reimagine how these valuable ways of working can be embedded across everything we do. Sometimes it means making this work visible, using a shared language to bring coherence – and crucially – committing, even in tough times, to honest reflection on our practice and a determination to keep improving.

The waypoint moment

I’ve found it helpful to describe civic engagement as an expedition. Most of us can imagine some kind of destination for our civic ambitions – perhaps obscured by clouds – with many paths before us, lots of different terrains, and a few hazards on the trail.

Through the NCIA’s work – led by Sheffield Hallam University in partnership with the National Coordinating Centre for Public Engagement (NCCPE), the Institute for Community Studies, City-REDI, and Queen Mary University of London – we’ve distilled three years of intensive evidence gathering and experimentation into fourteen practical “waypoints” for civic engagement, now launching as part of our Civic Field Guide (currently in Beta version).

These aren’t just statements – they’re navigation signals based on well-trodden paths from fellow explorers. They come with a bespoke set of tools, ideas and options to deal with the terrain ahead.

You can think of them like those reassuring signs on coastal walks. Helping you understand where you are and what direction you’re heading but giving you freedom to explore or take a detour.

Take our waypoint on measuring civic impact. It encourages universities to develop evaluation systems that can document progress quantitatively, alongside the rich narratives that illustrate how civic initiatives transform real lives and strengthen community capacity. It draws on examples from universities that have tried to tackle this challenge, acknowledging both their successes and the obstacles they’ve encountered, whilst offering practical tools, frameworks and actionable guidance. But it deliberately avoids prescribing a one-size-fits-all measurement approach. Because every place has different needs, ambitions and challenges. Both the civic work itself and how we measure it must be tailored to the unique character of our places and communities.

Our waypoints cover everything from embedding civic engagement as a core institutional mission to navigating complex policy landscapes. They address the “passion trap” that many of us might recognise, where civic work is reliant on a few individual champions rather than an institutional culture. They tackle issues of partnership development, cultivating active citizenship, and contributing to regional policymaking.

Perhaps most importantly, they recognise that authentic civic engagement isn’t about universities doing things to or even for their places, it’s about embracing other anchor institutions, competitors, businesses and communities as equal partners throughout the entire process of identifying needs, designing solutions, and implementing change.

This often means decentring the university from the relationship. Some of the strongest partnerships start with universities asking not “what can we do for you?” but “what are you already trying to achieve, and how might we contribute?”.

The embedding challenge

James Coe’s recent thoughts on how to save the civic agenda challenged us all to think about how universities move beyond “civic-washing” to genuine transformation. The NCIA’s evidence suggests the answer lies in weaving civic responsibility into everything we do, not just the obvious.

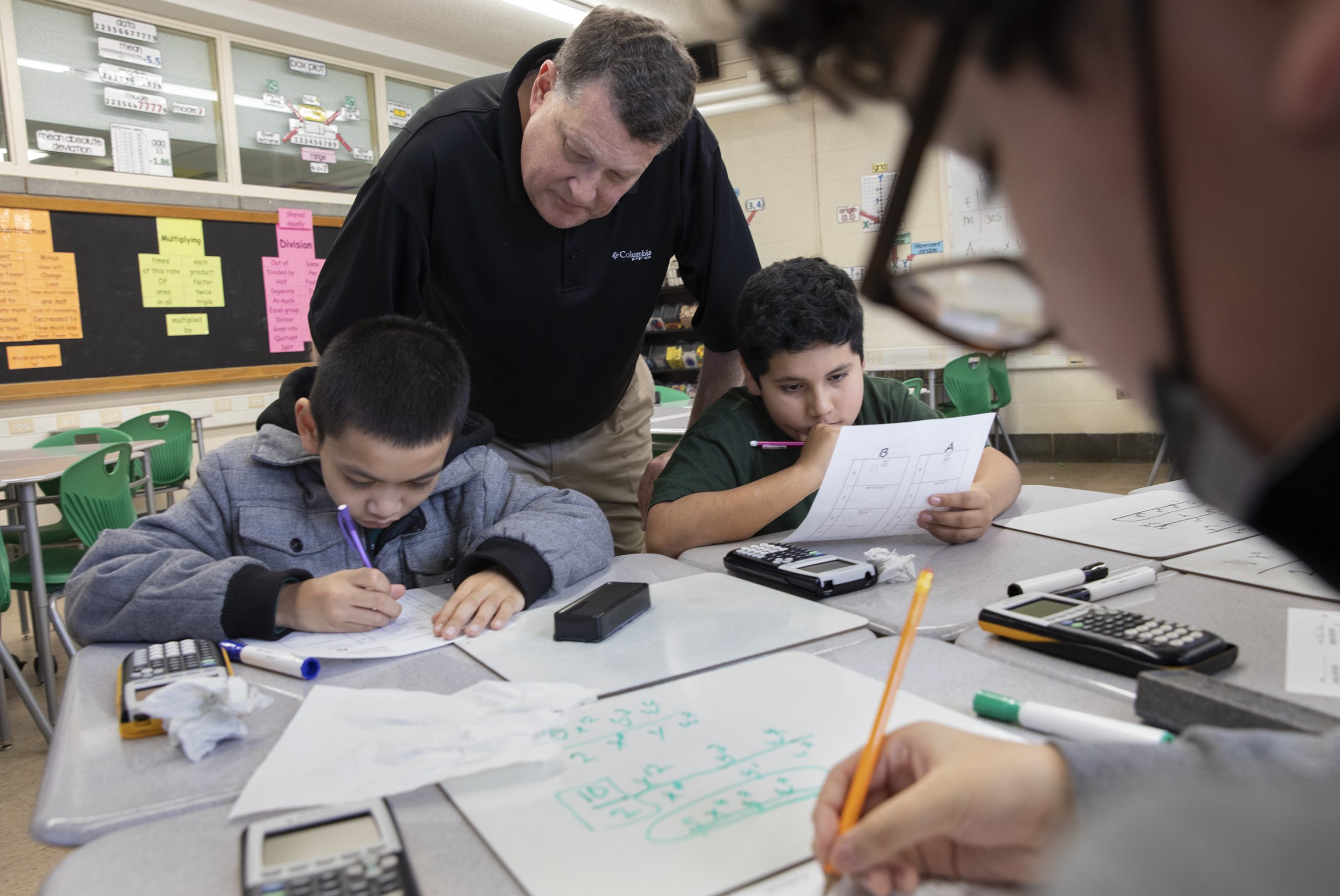

Being civic means thinking about procurement policies that support local businesses. It means campus facilities genuinely accessible to community groups. It means research questions shaped by community priorities, not just academic curiosity. It means student placements that address local challenges whilst developing skills and confidence.

Such as at the University of Derby. Their CivicLAB supports academics, students and the community to share insights on research and practice through a place-based approach to knowledge generation. Located centrally within the university, this interdisciplinary group cuts across research, innovation, teaching, and learning. Established in late 2020, CivicLAB has already created civic opportunities for over 14,600 staff, students and external stakeholders and members of the public.

The civic question also means responding to the sceptics with evidence: demonstrating how place-based engagement creates richer contexts for research and more meaningful experiences for students; showing how equitable partnerships, far from distracting from core academic work, can actually enhance teaching and scholarship; and providing examples of how civic engagement has strengthened global excellence, helping local communities connect their priorities and assets to broader movements and opportunities.

The future of civic engagement

At CiviCon25 – our national, flagship conference which took place in Sheffield last month – we brought together civic university practitioners, engaged scholars, senior leaders and community partners to wrestle with the challenges that will shape the next decade of civic engagement.

Our theme of “where ideas meet impact” captured something fundamental about our work: too often in higher education, brilliant ideas never quite make it into practice, or practice develops in isolation from the best thinking. We sometimes get stuck reinventing the wheel, endlessly debating definitions instead of delivering for our communities.

But something different is happening now. A new generation of determined, ambitious civic universities are leading this movement forward, and I’ve been privileged to witness their journeys first-hand. They’ve been extraordinarily generous. Sharing what’s worked, being honest about setbacks, and helping others navigate the same challenges many of them faced alone. It’s their insights, experiments, and wisdom that have shaped the NCIA’s fourteen waypoints.

As the NCIA draws to its scheduled conclusion, there’s something bittersweet about this moment. The infrastructure exists. The evidence is compelling. The policy environment has never been more supportive. But whatever happens next, we need to demonstrate our value to society collectively and commit to reflect and do better despite the financial challenges.

The civic trail will always have its hazards. We’ve learned that much. But with good maps, experienced guides, and companions who share the commitment to reach the destination, these hazards become navigable challenges rather than insurmountable barriers.

The fourteen waypoints offer the higher education sector a map and compass. Not every university need follow this path, but those that choose civic engagement as core mission must commit fully to the patient work of institutional change, equitable partnership building, and community-led impact.

The trail is well marked now. The question is: who else will join the journey?