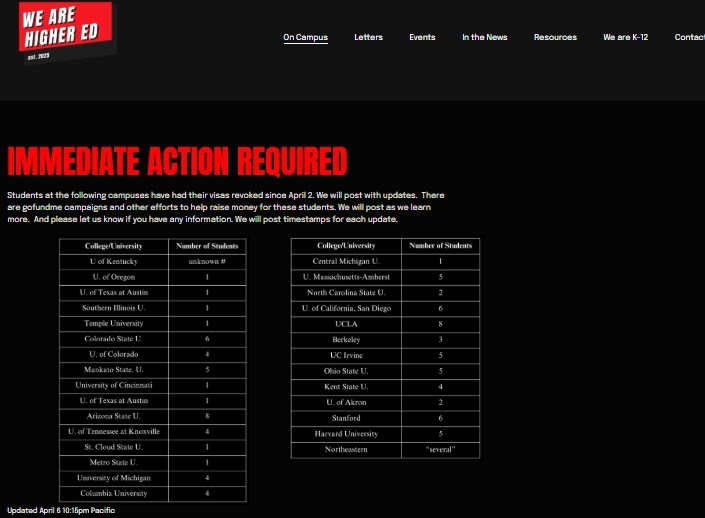

Reports have surfaced of a significant increase in the number of international student visas being revoked and students being detained across various universities in the United States. This follows heightened immigration scrutiny, particularly under the administration of Donald Trump. According to Senator Marco Rubio, more than 300 international student visas have been pulled in recent months, primarily targeting students involved in political activism or minor infractions. WeAreHigherEd has named 30 schools where students’ visas have been revoked.

Campus Abductions — We Are Higher Ed

Key Universities Affected

-

University of California System (UCLA, UC San Diego, UC Berkeley):

Universities within the University of California system, which hosts a large international student population, have reported multiple visa cancellations. These revocations have affected students involved in pro-Palestinian protests, political activism, or perceived violations of U.S. immigration policies. For instance, the University of California has seen as many as 20 students affected in recent weeks. -

Columbia University:

At Columbia University, the case of Mahmoud Khalil, a student activist, has gained significant media attention. Khalil, who was detained and faced deportation, exemplifies the growing concerns over student rights and the growing impact of politically charged visa revocations. -

Tufts University:

Tufts University is currently battling the Trump administration over the case of Rümeysa Öztürk, a Turkish graduate student whose visa was revoked. Her detention and the ensuing legal battles highlight the growing tensions between academic freedom and government policy. Tufts and its student body are advocating for Öztürk’s release and seeking clarification on the legal processes involved. -

University of Minnesota:

At the University of Minnesota, one international graduate student was detained as part of an ongoing federal crackdown on visa violations. The U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) actions continue to raise concerns over the rights of international students to remain in the country, especially as visa renewals and compliance checks become more stringent. -

Arizona State University:

Arizona State University has also reported incidents of international students having their visas revoked without prior notice. These revocations have affected students from various countries, creating uncertainty within the international student community at the university. -

Cornell University:

At Cornell University, international students have similarly faced unexpected visa cancellations. This has raised concerns about the ability of universities to adequately support their international student populations, as students are left to navigate the complexities of visa status without sufficient notice or explanation. -

North Carolina State University:

North Carolina State University is another institution where international students have had their visas revoked without notice. The university has expressed concern over the lack of clarity from immigration authorities, which has left students in a precarious situation. -

University of Oregon:

The University of Oregon has experienced several cases of international students having their visas revoked. This has been particularly troubling for students who were actively pursuing their education in the U.S. and now face the prospect of deportation or being forced to leave the country unexpectedly. -

University of Texas:

At the University of Texas, international students have faced visa issues, with several reports of revocations and detentions, affecting students who are working toward completing their degrees. This has sparked protests and advocacy efforts from both students and university administration, seeking more transparency in the process. -

University of Colorado:

The University of Colorado has similarly reported instances of international student visa revocations, particularly affecting those involved in political activism. The university has been working to support students impacted by these actions, although many are left in limbo regarding their ability to continue their studies. -

University of Michigan:

The University of Michigan has also been impacted by a wave of visa revocations. Similar to other institutions, students involved in political protests or activism have found themselves under scrutiny, facing the risk of detention or deportation. Students, faculty, and staff are pushing for clearer policies and legal protections to support international students, who are increasingly at risk due to the political environment.

The Broader Implications

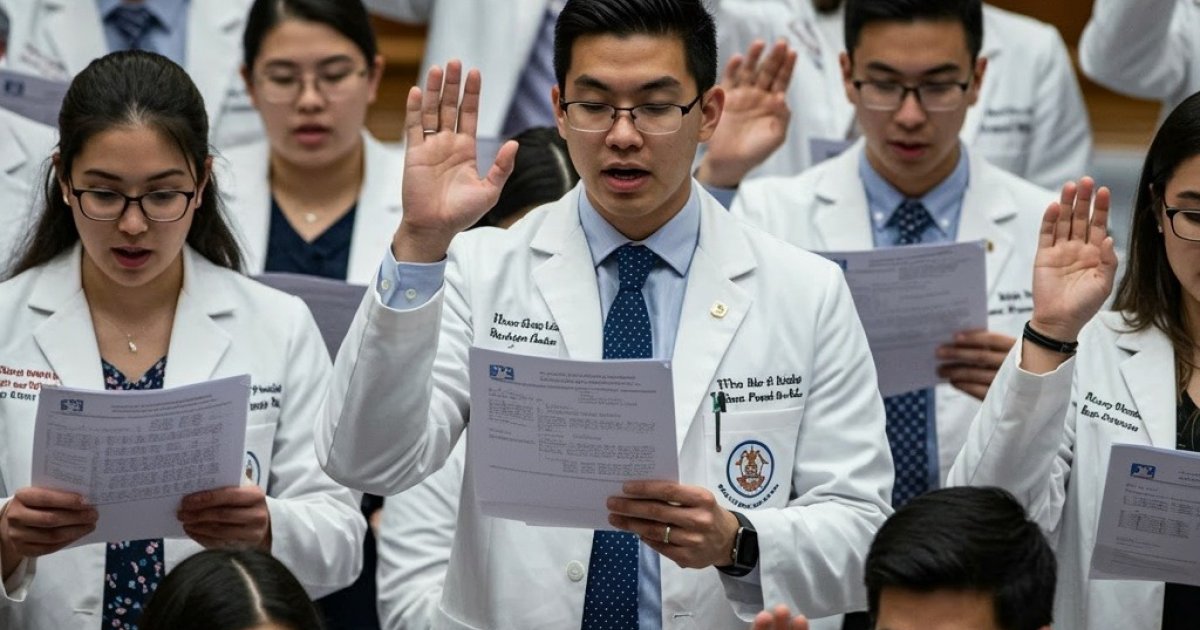

These incidents of visa revocation and detentions are seen as part of a broader trend of increasing immigration enforcement under the Trump administration. Critics argue that these actions infringe upon students’ rights, potentially violating freedom of speech and academic freedom. International students, especially those participating in protests or political discourse, have found themselves at risk of being detained or deported, with little prior notice or transparency regarding the reasons for such actions.

Moreover, the economic impact of these actions is significant. In 2023, a record 253,355 student visa applications were denied, representing a 36% refusal rate. This has major implications not only for the affected students but also for U.S. universities that rely heavily on international students for tuition revenue. The financial loss could be as much as $7.6 billion in tuition fees and living expenses, further emphasizing the broader consequences of these policies.

Legal and Administrative Responses

Many universities are rallying behind their international student populations, with advocacy efforts from institutions like Tufts University and Columbia University. These universities have criticized the abruptness of the visa cancellations and detentions, calling for more transparency and due process.

However, despite these efforts, the political climate surrounding U.S. immigration remains volatile, and it is unclear whether policy changes will result in more lenient or more restrictive measures for international students.

Conclusion

These stories underscore the fragile position of international students in the U.S. today. With incidents of detentions and visa revocations increasing, students face significant challenges navigating the complexities of U.S. immigration law, particularly those involved in political or activist circles. University administrations and students alike continue to call for clearer policies, protections for international student rights, and more transparent practices to avoid the unintended consequences of politically motivated visa actions.

This issue remains ongoing, with much at stake for both