Just weeks after he took office, the newly appointed U.S. Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary, Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., started keeping his promises to the alternative medicine community.

An outbreak of measles had started in Texas and he urged parents to treat their children with vitamin A or with cod liver oil, which contains both vitamins A and D.

He downplayed the need for vaccination against measles, also in keeping with his longtime anti-vaccination campaigns. Within a short time, children were needing treatment for both measles and vitamin A toxicity.

Vitamin A, it turns out, is an effective treatment for measles in developing countries where children are malnourished, but not in countries like the United States where they are not. Kennedy has since backed off of this particular recommendation, but measles continues to rage across the United States and Canada.

And the alternative medicine industry is more hopeful than it’s ever been, thanks both to a supplement-friendly HHS and to a global population that’s taken a new interest in vitamins, supplements and alternative treatments in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic.

And why not? Why not let Kennedy and others disrupt the comfortable and profitable medical establishment?

The big money in Big Pharma

One basic tenet of journalism is to follow the money, and the pharmaceutical industry does indeed make a great deal of money — $1.6 trillion globally in 2024, according to Grand View research. Who hasn’t gasped at hearing about the $1,000-per-month cost of the weight-loss drug Ozempic and wondered, for instance, whether a cheap, natural alternative called berberine might not be just as good?

Influencers sure seem to think so. Legitimate doctors, not so much.

Videos abound in which genuine-seeming folk attest to their weight loss with berberine, or a person identifying as a doctor outlines the various benefits of vitamin D or warns of the supposed secret dangers of prescription drugs. If they’re not making money off the ads on these videos, they are all almost certainly selling their own supplements.

Plus, here’s one big difference between Ozempic and berberine: Novo Nordisk, the global pharmaceutical company that makes Ozempic, had to prove it works. There’s a lengthy process for making, testing and gaining approval of any prescription drug.

First developed to treat diabetes, Ozempic is based on a component taken from the venom of a Gila monster lizard.

After what are called preclinical trials in laboratories and in animals, the company had to prove the drug was safe in a small group of patients. These are called phase 1 clinical trials. A second round of trials, called phase 2 trials, test the drug in a larger group of patients. It’s not until phase 3 trials, done in hundreds or even thousands of people, that a company can really begin to see if a drug might actually work as hoped.

Most experimental drugs never make it to phase 3.

Developing drugs is costly.

At first, Ozempic was only tested as a diabetes drug. It wasn’t until doctors noticed their patients were also dropping weight that Novo Nordisk saw the potential for selling it as an obesity drug. The company had to perform another round of trials to prove it worked safely as a weight-loss agent, as well, before it could market it as one.

At the same time, other companies were racing to develop their own rival drugs, so the company’s investment was steadily being diluted by competition.

The factories where Ozempic is made are inspected for cleanliness, safety and other aspects of what is known as good manufacturing practice or GMP. Each dose must be exactly the same as the next. The dosing is carefully calculated for prescription — no guessing allowed.

The process is expensive — anywhere between $950 million and $1.3 billion per drug, according to a study in the journal JAMA Network Open.

The labelling, advertising and prescribing are all carefully regulated. Expert committees meet to advise the U.S. Food and Drug Administration on whether to approve the drug and they meet to advise on any changes to prescribing advice. And the manufacturer must go through similar processes for every approving authority in the United Kingdom, Europe, Canada and other countries where they hope to market the product.

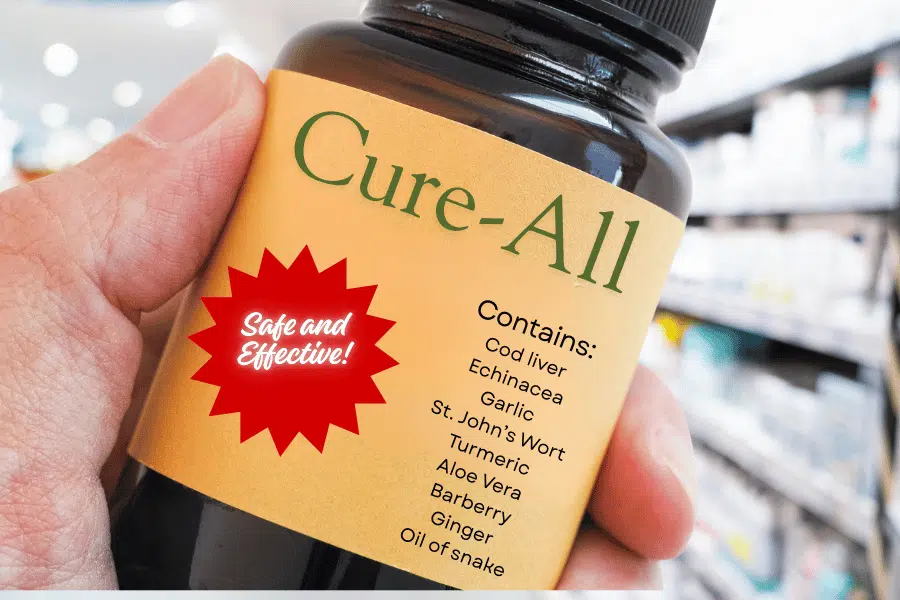

Compare that to the risks being taken by the many different makers of a supplement such as berberine. All they have to do is fill capsules with a product they affirm is berberine. In the United States, no regulatory authority even tests it to ensure that it is, in fact, something that contains berberine — which is a plant extract.

Untested medicine

No regulator tests any of these herbal products to ensure that they work as advertised, or even to see if they are safe, although some makers submit to voluntary standards. And the industry can take advantage of that.

“When it comes to the dietary supplement marketplace, misinformation, exaggeration, deception and even scams abound,” says the Center for Science in the Public Interest, a nonprofit that investigates health issues.

But doesn’t the lack of regulation allow the natural products industry to sell people cheaper products? Maybe so, but it also allows for big, big profits. The supplement industry drew in $69 billion in the United States last year, $192 billion globally, according to Grand View.

“If you look at the supplement industry, it’s a multibillion-dollar industry where people are making a ton of money off of a lot of things that have limited research and data,” said Dr. Fatima Cody Stanford, an obesity specialist at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

The Council for Responsible Nutrition, the group that represents vitamin and supplement makers in the United States, estimates that three-quarters of Americans take at least one. That’s even though there is little evidence they do much good at all. Independent research shows that multivitamins do not lower the risk of cancer, heart disease or memory loss.

How effective are vitamin supplements?

The Cochrane Library — widely accepted by medical groups around the world as the last word in determining whether a medical treatment works — commissioned a study in 2013 to determine whether vitamin C can prevent colds. It doesn’t. If echinacea does, the effect is so slight it’s barely noticeable.

And overdosing on some supplements can in fact raise the risk of some cancers. One study showed too much beta carotene raised the risk of lung cancer in smokers and former smokers.

And these are the very few of the 100,000 or so supplements on the market that have been tested for efficacy. The vast majority have not been.

In the United States, that’s on purpose. The 1994 Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act defines supplements as food, and excludes them from regulation by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. So while a pharmaceutical manufacturer must go through many defined steps to prove a product is safe and effective, a supplement maker has no such requirements.

Similarly, in the European Union, supplements are regulated as foods. And while these regulations in the EU, Canada and China are stricter than in the United States, in general, globally, supplements get much, much less scrutiny than pharmaceutical products do.

Testing the safety of drugs

The result is that some products contain little or none of what they purport to contain. Others can be adulterated with toxic material such as lead. Still others contain, believe it or not, actual pharmaceutical products. These are just the very few that get caught by the FDA with the tiny budget it has for policing contaminated supplements.

Does that mean all prescription drugs are perfectly safe? No, but their makers have at least jumped through hoops to demonstrate that they are and can be held accountable when they are shown not to be. Unlike a supplement maker who can disappear by shutting down a website, a pharmaceutical manufacturer’s factory has a fixed address, known assets and bank accounts that can be seized in legal actions.

So influencers are free to go online, touting this or that supplement for this or that condition and swearing it works. They do not have to disclose if they are getting paid.

Now some of those influencers have positions in the U.S. government. One, Dr. Mehmet Oz, heads the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Oz was once hauled before the Senate and scolded for endorsing sketchy health products on a national television show he hosted.

President Donald Trump’s nominee for Surgeon General, Dr. Casey Means, advertises a commercial supplement product in her newsletter online. In that newsletter Means also questions the safety of childhood vaccines — the safety of which has been demonstrated steadily over decades.

Her family also has financial entanglements with both the supplements and tobacco industries, ties she failed to disclose until after an investigative report by the Associated Press.

The Trump Administration’s Make America Healthy Again influencers, known as MAHA, “strike a chord” by pointing out the corporate interests of the pharmaceutical industry, the nonprofit group Public Citizen said in a report.

“But rather than fighting to lower drug prices, ensure safety for patients, or build a more equitable health system for all, they sell consumers their own version of the grift: excessive testing, unproven and underregulated health supplements,” Public Citizen’s Eileen O’Grady said in a statement.

Questions to consider:

1. Doctors like to say anecdotes don’t equal data. What do you think that means?

2. Why is it significant that so much money is made off off medicinal products?

3. Why should you not trust medical advice from friends or social media?