Bryce Loo, Associate Director of Higher Education Research

International students navigate a landscape of uncertainty and opportunity, as the 2024 IIE Open Doors Report highlights shifting trends in U.S. enrollment and global migration.

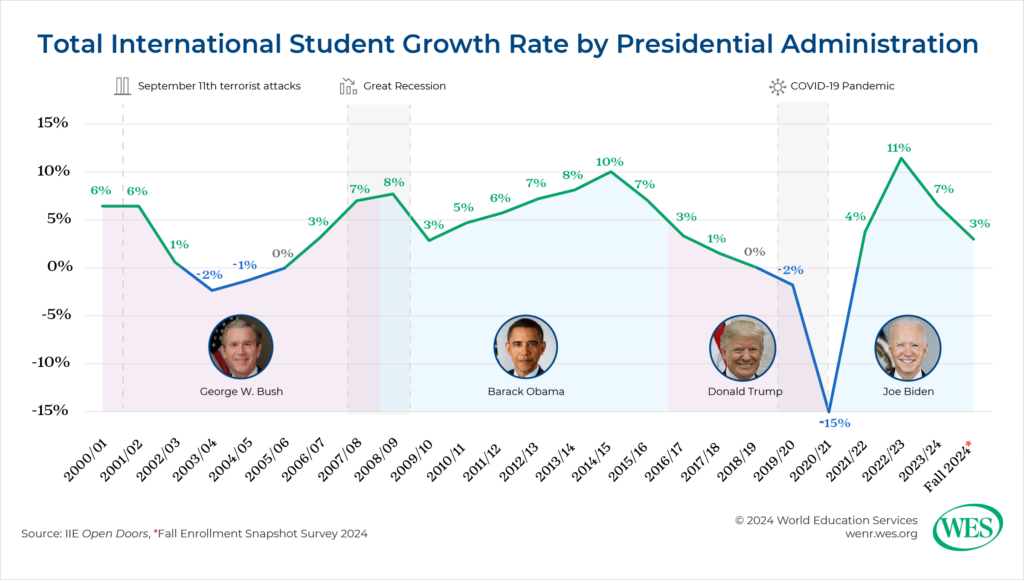

The Institute of International Education’s (IIE) annual Open Doors Report on International Education Exchange (Open Doors, for short),[1] along with its companion Fall Enrollment Snapshot Survey (Fall Snapshot Survey, for short),[2] was released only a few weeks after a consequential presidential election in which former president Donald Trump defeated Vice President Kamala Harris. Trump’s win will significantly shift the landscape around international students in the U.S.

Open Doors is a retrospective report on international enrollment and other student data in the U.S., focused on the previous full academic year—in this case 2023-24.[3] The Fall Snapshot Survey provides insights into the current fall term. But uncertainty abounds in this new environment with the return of Trump, known for his tough stances on immigration, which may affect non-immigrant residents such as international students and temporary workers. This is happening against a backdrop of global uncertainty, in a year with a tremendous number of important elections around the world, many armed conflicts, and growing climate change. At the same time, there are bright spots for the U.S. as a host of international students and for global student migration in general.

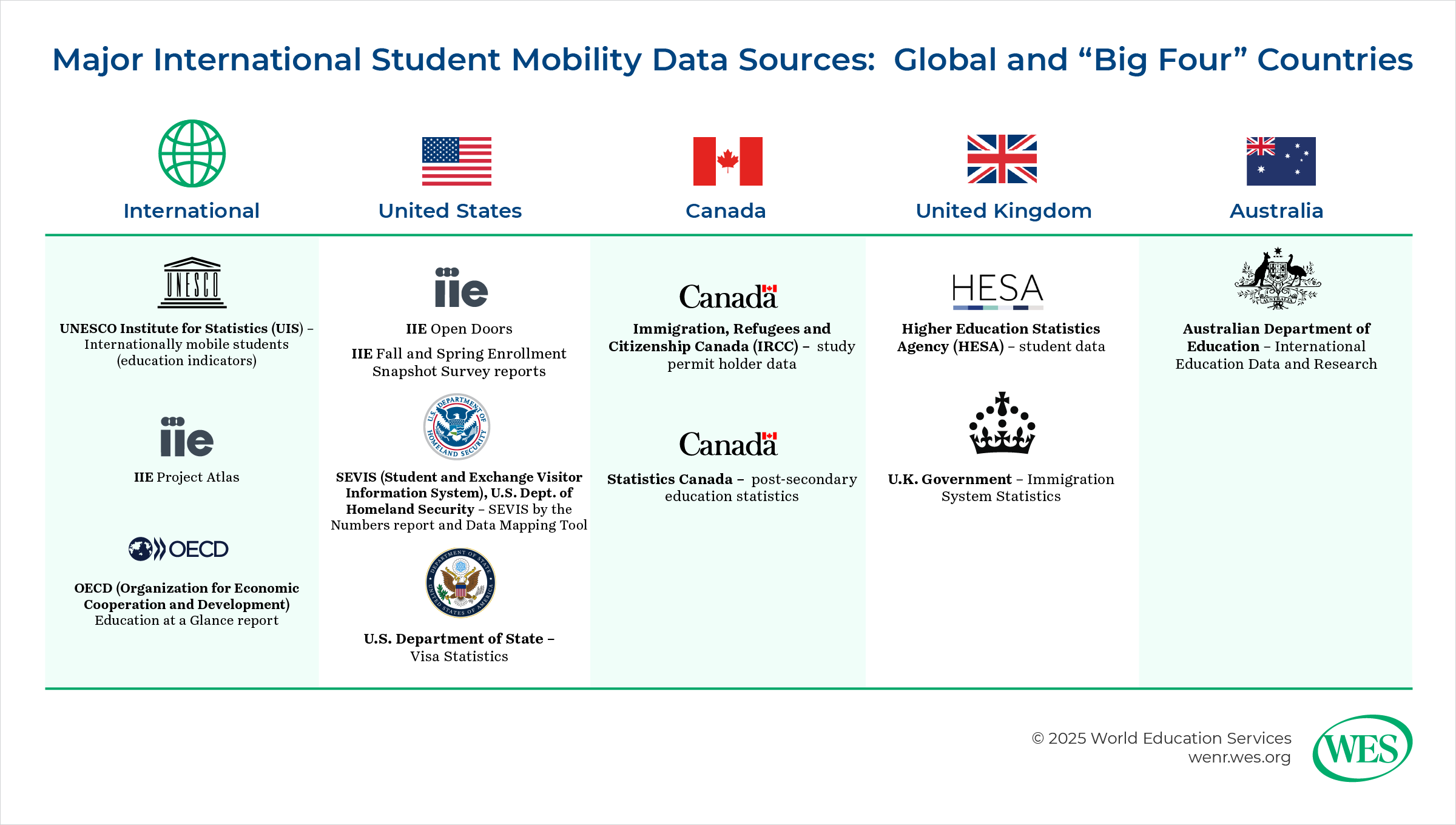

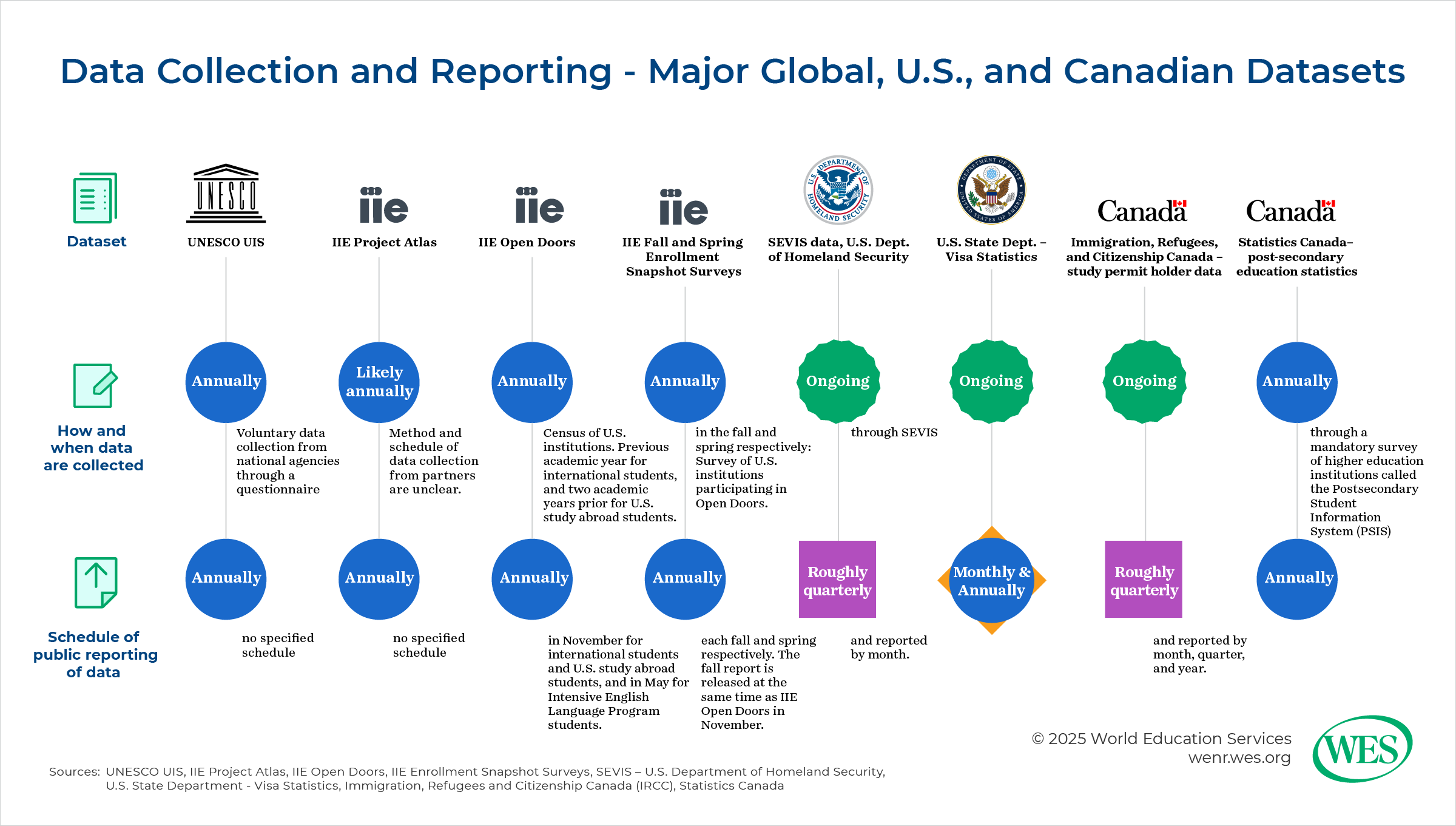

In this article, I also compare results from Open Doors and the Fall Snapshot Survey against recently released data from SEVIS (the Student Exchange and Visitor Information System), maintained by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), for Fall 2024.[4] This dataset captures all students with a record in SEVIS, the U.S. government database in which all international students are required to be registered by their hosting U.S. institution. Data are organized monthly, with the most recently released is for November 2024, and they vary little month-to-month within a given term, such as a fall semester. For consistency, I compare November 2024 with November 2023. Such data help us to gain a fuller picture of current international enrollment trends this fall.

What the data tell us: Continued but leveling growth

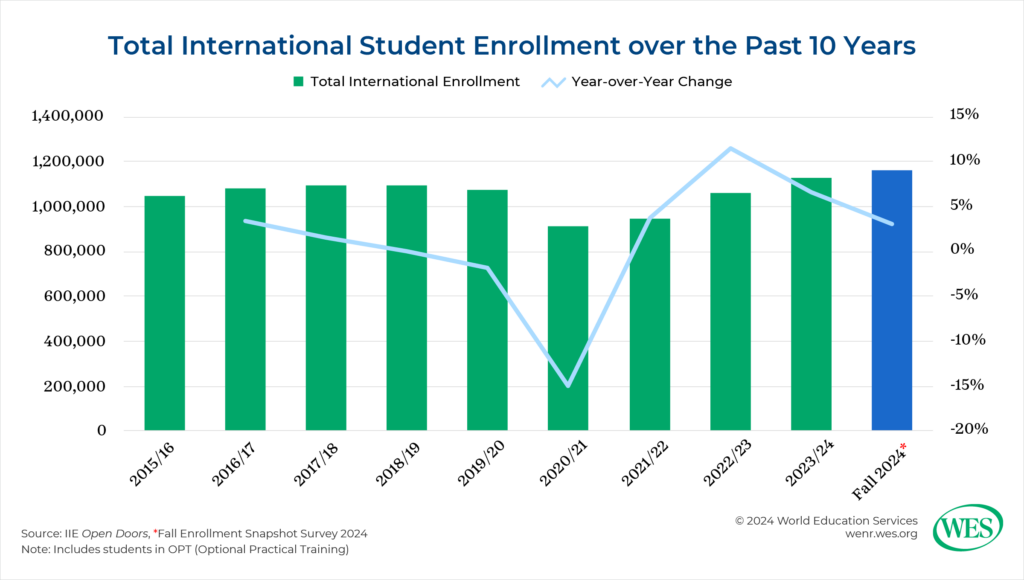

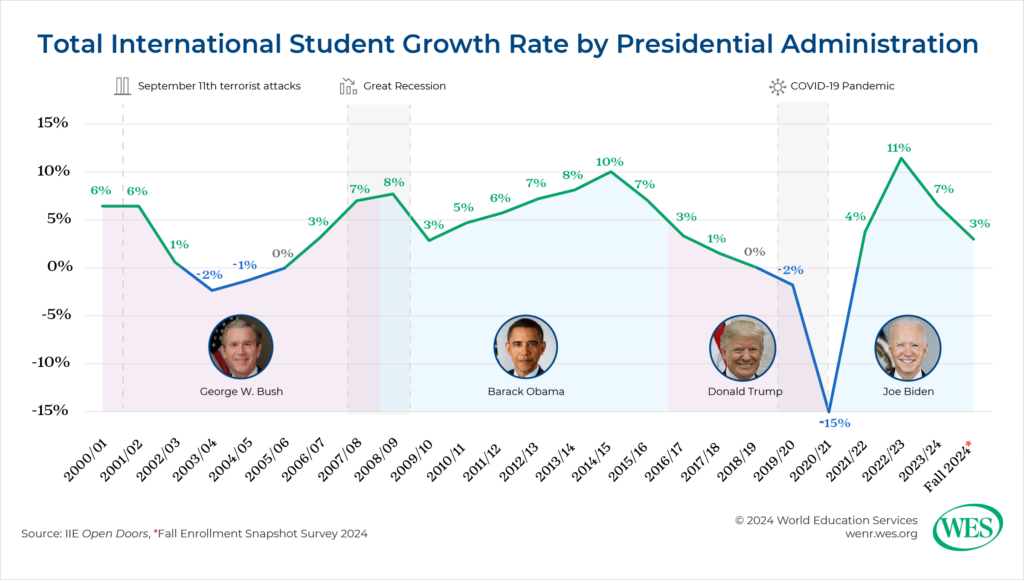

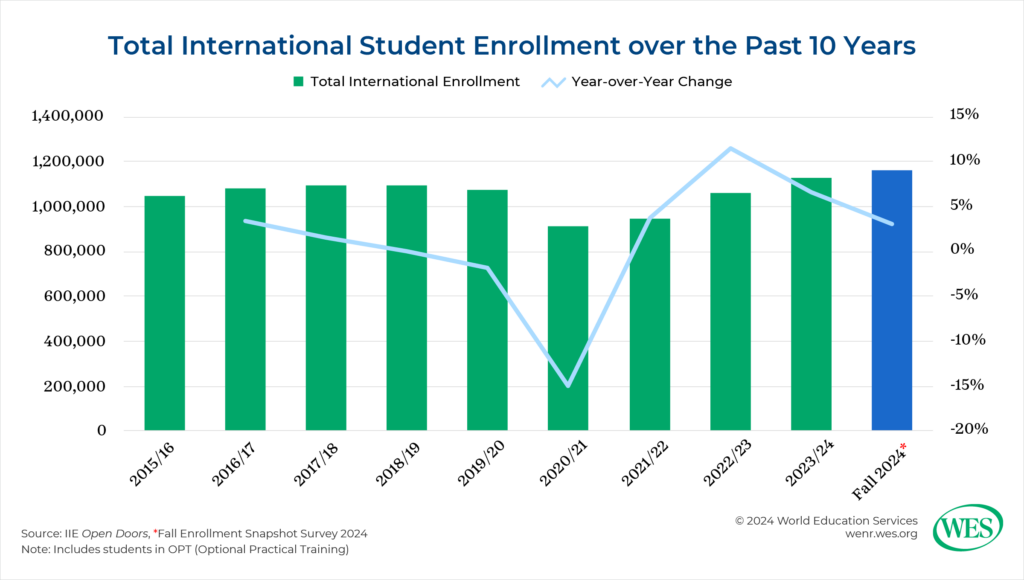

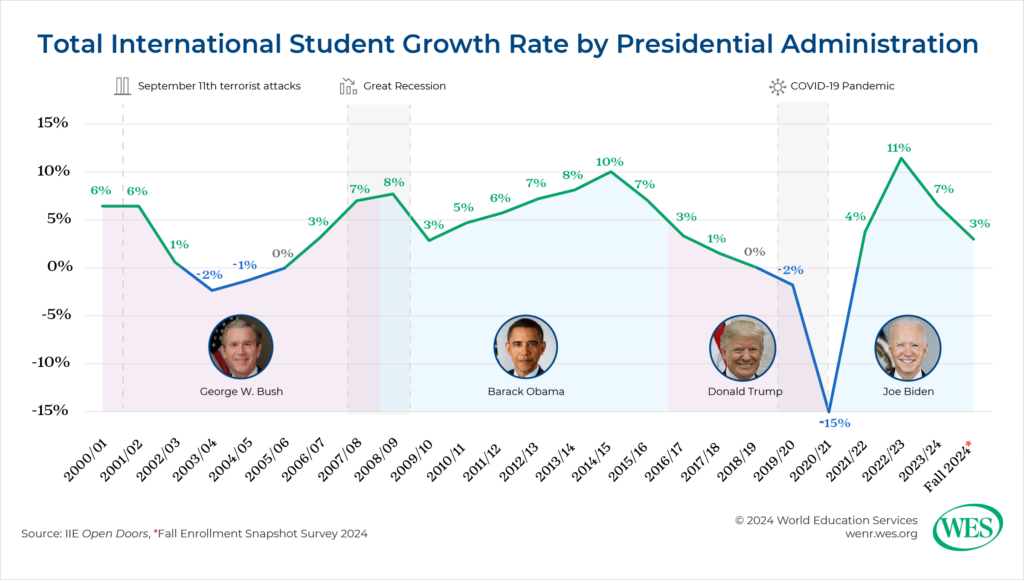

Total international student enrollment in the U.S. hit an all-time high of 1,126,690 in 2023–24, a growth rate of 6.6 percent from the previous year. This has followed a few years of recovery following the dramatic enrollment decrease during the COVID-19 pandemic. The post-pandemic growth rate peaked in 2022-23 at 11.5 percent.

However, growth is slowing. While this year’s Fall Snapshot Survey indicates a 3 percent growth rate in fall 2024, analysis of the SEVIS data indicates a drop in overall enrollment. International enrollment is down to 1,091,190 students in November 2024, a 10 percent decrease from the previous November, according to SEVIS records.[5] IIE’s data confirms slowing growth, too. New international student enrollment slowed to only 0.1 percent in 2023-24. Additionally, the Fall Snapshot Survey indicates a 5 percent decrease in new students this fall.

This recent slowdown, which happened prior to the presidential election results, is tricky to diagnose. One likely culprit, though certainly not the only one, is economics: An education in the U.S. has become particularly expensive, due largely to a combination of inflation and a strong U.S. dollar. A more expensive U.S. education particularly impacts many students from South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, the two regions showing the strongest rise in U.S. international enrollment in recent years, who are particularly price sensitive.

Changing trends in South Asia and East Asia

International enrollments in the U.S. from South Asia, driven dominantly by India, continued growing at a rapid rate in 2023–24. In 2023–24, India became the top country of origin among international students in the U.S. and by a substantial margin, at 331, 602 students. There was about a 23 percent increase in Indian students from the previous year, accounting for almost 30 percent of all international students in the U.S.

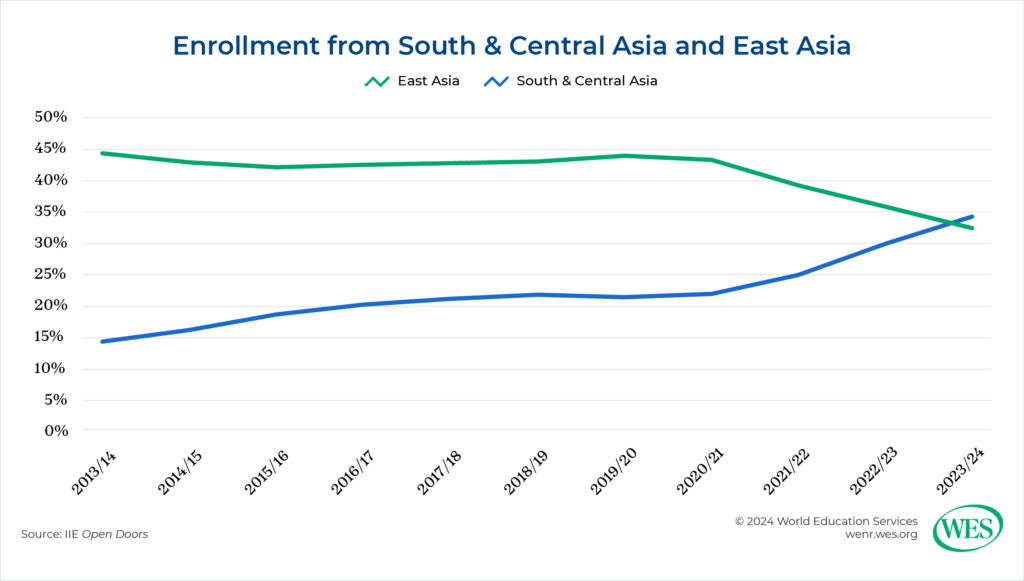

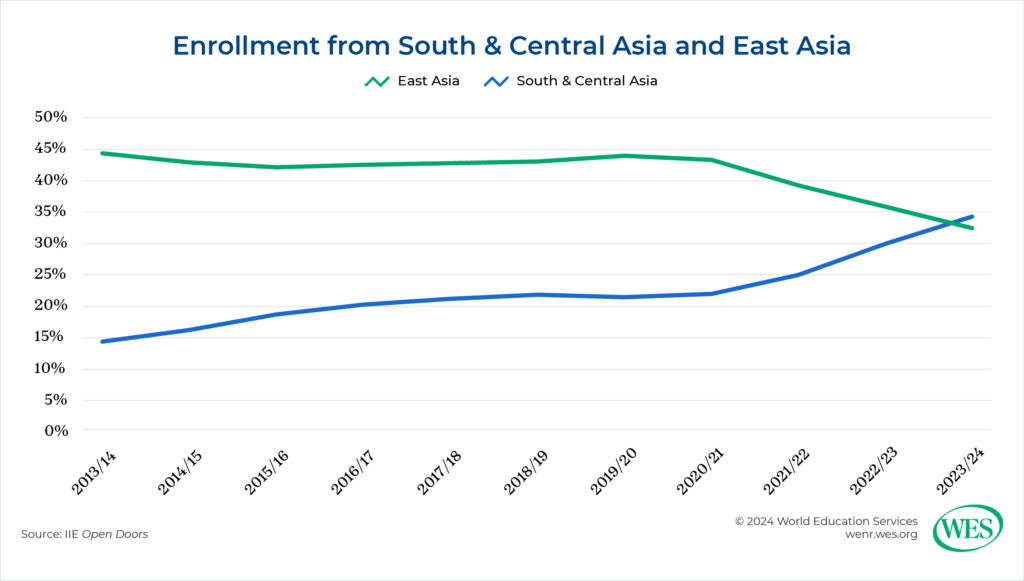

In 2023-24, South Asia firmly dominated among regions of origin for U.S. international students and its numbers continue to rise. South and Central Asia (which IIE groups together as one[6]) account for one-third (34.3 percent) of all U.S. international students, just ahead of East Asia. South and Central Asia’s sending numbers grew 22 percent over the last year, more than those of any other region. Beyond India, there continues to be robust enrollment growth from Bangladesh (26 percent), Nepal (11 percent), Sri Lanka (10 percent), and Pakistan (8 percent). Bangladesh and Nepal broke into the top 10 countries of origin in 2023-24.

By contrast, the number of Chinese students in the U.S. declined more than 4 percent to 277,398 during the same period and accounted for less than 25 percent of all U.S. international students. Overall, numbers from East Asia are declining steadily (by nearly 4 percent last academic year). Numbers from South Korea (-2 percent) and Japan (-13 percent) continued to drop. The one bright spot among major East Asian nations was Taiwan, which saw a 6 percent rise from the previous year and was the fifth largest sending country. Students from East Asia have been decreasing in the last few years, and forecasts suggest further steady decline.

For many East Asian students, the calculus about studying in the U.S. and in Western countries has changed in recent years. Holding a degree from a highly ranked U.S. or Western institution holds less cachet than it once did. In both China and South Korea, local universities have become more prestigious and offer students the opportunity to connect directly with the local job market, putting those studying far afield at a disadvantage. For Chinese students, geopolitical tensions and strict policies against Chinese students and scholars largely enacted by the first Trump Administration, many of which were continued by the Biden Administration, may make studying in the U.S. feel riskier. There has also been growing intra-regional mobility, with many East Asian students choosing to go to another country in the region. According to the British Council, for example, there are more Japanese students in China than in any anglophone country.

Despite the recent increases in enrollment from South Asia, the SEVIS data show a rapid reversal of trends heading in Fall 2024. Indian enrollment in the U.S. this fall has declined by 24 percent, and overall South Asian enrollment has fallen at a similar rate. Meanwhile, Chinese and overall East Asian enrollment has flatlined, each with a barely perceptible decrease. As a result, however, China has become the top country of origin once again, with 263,523 students in the U.S., followed by India (25,5443), in Fall 2024. Likewise, East Asia has returned to the top spot among region of origin, with modest enrollment increases from Japan and South Korea.

A slowdown of enrollment growth from South Asia likely is attributable to rising costs in the U.S., particularly given currency exchange rates, as noted earlier. Safety, a frequent concern for Indian students and their families, could also be a factor. Many Indian media outlets, such as The Economic Times and The Indian Express, have recently reported on increasing safety issues for Indian students in the U.S.

That said, these declines from India and South Asia do not necessarily foretell a long-term trend. Many prominent models, notably that of HolonIQ, predict growth from India into 2030.

Graduate students continue to dominate. For now.

International student growth in the U.S. continues to be driven at the graduate level, particularly among master’s degree students. Graduate students made up almost 45 percent of all U.S. international enrollment in 2023-24. Total international student graduate enrollment increased by 7.6 percent in 2023-24, while undergraduate enrollment fell by 1.4 percent and non-degree enrollment fell by 11.5 percent. These trends are somewhat parallel with new international student enrollment. India has driven much of this growth in grad students, as have South and Central Asian students in general. More Chinese students came to study at the graduate level that year, too.

This growth of international graduate students does not appear to be holding into 2024-25, however. The Fall Snapshot Survey indicates a slight decrease of about 2 percent in international grad students this fall and an increase (6 percent) in international undergrad students. The SEVIS numbers show decreases for both, including a significant decrease of 15 percent among international grad students. (International undergrad enrollment declined by 3 percent.) However, international graduate enrollment is still greater than undergraduate enrollment currently.

The decrease in international graduate students appears to be driven by Indian students and South Asian students overall. Indian students account for about 40 percent of all U.S. international student graduate students, and 60 percent of Indian students in the U.S. are studying at the graduate level, according to Open Doors. Per the SEVIS data, Indian graduate enrollment in the U.S. declined by almost 26 percent in Fall 2024. Additionally, South and Central Asian and East Asian student together account for nearly three-quarters of all international graduate students. Chinese graduate enrollment in the U.S. decreased about 4 percent this fall, according to the data from SEVIS.

U.S. universities and colleges continue to focus heavily on India and to a lesser extent China for their international student recruitment, according to the Fall Snapshot Survey. India is the top country of focus for both graduate students (81 percent of respondents) and undergrads (65 percent). China was second top country of focus for grad students and third for undergrads (just after Vietnam). Given the volatility of enrollment from India and steady declines from China, U.S. institutions may wish to ensure diversity of countries from which they recruit.

What could impact international enrollment in the near future?

The Trump Administration

When it comes to potential impacts on international student enrollment in the U.S., a primary factor will be the incoming Trump administration. Donald Trump will take office with a decisive agenda, having campaigned and won with a tough-on-immigration stance. This stance seemed to resonate with many voters, along with concerns about the economy and inflation.

The first Trump administration may provide a useful look at what could happen in the second one. Trump’s first term brought a decline in international student enrollment, due in part to policies like the 2017 travel ban and a slowdown in visa processing. This trend reversed somewhat during the Biden administration but could resume under the policies of a second Trump term.

Going forward, much will depend on the incoming administration’s policies as well as rhetoric. Trump’s immigration agenda is mostly focused on asylum, primarily at the U.S.-Mexico border, and on undocumented immigrants, whom he has pledged to deport at unprecedented rates. The extent that he will focus on international students and immigrants with specialty occupations, notably the H1-B visa program under which some international students seek to remain in the U.S., is unclear. In June 2024, Trump, known for making offhand comments, proposed on a podcast hosted by Silicon Valley investors that international students who graduate from U.S. institutions, including community colleges, should receive a green card (permanent residency). He and his team later walked back that remark, and many commentators see such policy as highly unlikely given Trump’s overall immigration stance. In fact, reports suggest the administration is likely to limit pathways to H1-B visas, international students’ primary means of staying in the U.S. beyond Optional Practical Training (OPT), effectively making such visas virtually inaccessible.

Policy changes under Trump’s second administration could also affect OPT and “duration of status,” the length of time students with visas have been allowed to stay in the U.S. without needing to renew. Such changes were attempted in the first Trump administration but did not succeed. His first administration also tried to eliminate STEM OPT, the 24-month extension of OPT for those graduating with a degree in fields related to science, technology, engineering, or mathematics. Indian students in particular may be concerned about such changes if they are proposed again, as they are often drawn to the U.S. by opportunities to gain work experience. Toward the end of that term the administration also put forward a rule to limit duration of status to a finite period of two or four years, rather than allow the time needed to finish earning a degree, after which a student would be required to pay a fee and renew.

Still, it is possible to overestimate the attitudinal impact of a presidential administration, and recent survey research by Intead and Studyportals found a majority of prospective international students this fall were “indifferent” to the election outcome and how it might affect their plans to study in the U.S., according to The PIE News. There is certainly no monolithic view of President-elect Trump or U.S. politics among international students. If any declines in numbers happen again under Trump, it will likely be in response to policies that specifically impact international students or rhetoric aimed at individuals from their home country or region of origin. It may also be driven in part by visa delays and denials caused by administration policies.

Policies and politics in other major host countries

One other major factor is current policy changes in other major host countries, driven largely by politics and public opinion, which might actually boost the attractiveness of the U.S. The other three Big Four predominantly anglophone destinations—Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom—have had massive international student enrollment in recent years, particularly as a percentage of total higher education enrollment. According to IIE’s Project Atlas, Canada’s international enrollment rate in 2023 was 30 percent, Australia’s was 24 percent, and the U.K.’s was 22 percent. (By contrast, only 6 percent of U.S. higher education students were international, although overall size of its system makes the U.S. numerically the top enroller of international students.) Canada’s enrollment in particular has seen explosive growth, a rise of nearly 70 percent from 2019 to 2023. Many Canadian locales have struggled to accommodate such an influx, often viewed as a way to fill provincial funding gaps yet sometimes lacking steps to ensure students’ well-being.

Additionally, international students have been ensnared in broader immigration debates within these three countries, often being unfairly blamed for systemic housing and employment challenges, among other issues. As in the U.S., immigration has been a major political topic in many Western countries and in recent elections in France and the U.K.

As a result, the other three Big Four countries have begun implementing policies designed to rein in international enrollment growth and limit access to opportunities to work and stay after graduation. Canada, which according to IIE’s recent Open Doors briefing just overtook the U.K. to become the second most popular international student destination, adopted new policies in rapid-fire succession from late 2023 to fall 2024. The most consequential is a cap on the number of study permits (required in Canada for international students) granted per province, particularly meant to limit growth in higher-enrollment provinces, in 2024 and 2025. Other new policies include a significant hike in the financial resources international students are required to demonstrate, restrictions on work permits for spouses, limits on permission to work during study, and stricter requirements for obtaining the popular post-graduation work permit (PGWP), which allows graduated students to work in Canada and often transition to permanent residency.

The Australian government is strongly considering similar caps on international student enrollment in an attempt to reduce overall migration to the country. Already it has stricter visa regulations for international students, including stronger “tests” to ensure that prospective students are coming with the intention of studying, not working, as well as a significant increase in the visa fee. In the U.K. a new regulation enacted by the Conservative Party prohibits international students at all levels except postgraduate from bringing family members starting in 2024, in order to “slash migration and curb abuse of the immigration system,” according to the U.K, government. The new Labour government has opted not to reverse the policy.

The effects of these changes are already evident. The three other Big Four countries are all seeing declining applications for relevant visas and permits. Preliminary analysis of Canadian study permit application data shows the number of approved study permits will likely come in below the actual caps for 2024. The U.K. reported a 16 percent drop in student visa applications in summer 2024 compared to the same time period in 2023, and in Australia, the decrease in such applications has been particularly steep, nearly 40 percent from October 2023 to August 2024.

So far, the prospective beneficiary of these changes has been the U.S., according to both prospective student surveys and media reports. For example, in IDP Education’s Emerging Futures Report for 2024, a prominent series based on prospective student survey data, the U.S. came in second place (at 23 percent) as destination of choice for survey takers, just behind Australia (24 percent). Interest in the U.S. increased four percentage points; Australia’s percentage point declined by one. By contrast, interest in the U.K. and Canada decreased 1 percent and 9 percent respectively, dropping them to third and fourth places. In media coverage of the restrictions, Indian outlets such as Business Standard and The Indian Express note that many Indian students are switching focus to the U.S, although some, including the Express, also report students are looking beyond the Big Four to other study destinations entirely.

Still, President-elect Trump may introduce cuts or caps of his own, which, depending on their scope, may cause the U.S. to lose its developing enrollment edge. If all Big Four destinations have policies significantly cutting student influx, that could alter the student mobility landscape, shifting enrollments to other countries—notably, smaller anglophone destinations such as Ireland, New Zealand, and Singapore and non-predominantly anglophone countries in continental Europe and Asia—where English-taught programs have increased greatly in recent years.

Student mobility in an uncertain world

The incoming Trump administration and policy changes in other countries are only two factors apt to impact movement to the U.S.; internal issues in other countries and regions also come into play. For example, while U.S. policies and tensions with China have affected the number of Chinese students coming to the U.S., factors within China also played a role, as we examined in a recent series in WENR.

Worldwide, uncertainty and systemic challenges lie ahead. Several major conflicts, notably Russia’s war in Ukraine and escalated fighting in the Middle East, threaten to spiral into bigger geopolitical crises. Authoritarianism is rising around the globe, creating more potential crises, as is the threat of climate change, with 2024 recently declared the hottest year on record. Among its many effects, climate change will likely continue spurring global migration, including, increasingly, the forcibly displaced. In fact, all these factors will likely increase global migration. Luckily, U.S. institutions are well-placed to take in students from affected regions and offer them pathways for academic and professional growth.

In general terms, there is reason for optimism. Global student migration will continue and most likely rise, increasing economic and social opportunities for many globally mobile young people. International students also benefit their host societies, communities, and institutions, including domestic students, by bringing diverse international perspectives as well as economic benefits. By some estimates, international students will increase worldwide from about 6 million in 2023 to 10 million in 2030. The U.S. could host as many as 2 million, a still significant capacity compared to other destinations.

Despite domestic and international pressures, U.S. institutions can continue to demonstrate the value of a U.S. education and what unique value they in particular offer. They can continue to make clear, through channels like the #youarewelcomehere campaign, that international students are both accepted and embraced. Institutions can continue to show that international education benefits not only students and institutions but communities and the nation. For example, huge numbers of U.S.-based entrepreneurs and STEM professionals came to the U.S. as international students and have been an asset for U.S. business and research and development. And international educators can advocate for policies at local, state, and federal levels (for example, via NAFSA: Association of International Educators) that continue to make the U.S. a hospitable place for students from abroad.

Most important, U.S. institutions can and should take proactive steps to ensure inclusion and integration of their international students. This means initial support in everything from securing good housing to culturally sensitive mental health resources to campus career services that recognize international students’ unique needs. It may mean assisting students with financing in any way possible. It also means more efforts toward academic and social integration, which involves educating faculty, staff, and domestic students as well.

Looking to the future, U.S. policymakers, educators, and institutions must work together to create an environment that remains welcoming, inclusive, and responsive to the needs of international students. By doing so, the U.S. can maintain its position as a global leader in higher education and continue to benefit from the diverse perspectives and talents that international students bring.

[1] Open Doors is an annual census of international students (those on a nonimmigrant student visa) enrollment in U.S. higher education institutions, as well as U.S. students who studied abroad two academic years prior.

[2] The Fall Snapshot Survey is sent to all institutions that report data to IIE for Open Doors. This year, IIE collected 693 valid responses.

[3] Open Doors always tracks data from the previous full academic year.

[4] The SEVIS data released by DHS is usually the most up-to-date data available. Open Doors, however, provides more analysis and a greater breakdown of data compared with what is provided by SEVIS.

[5] Usually, IIE’s Fall Snapshot Survey aligns with current data trends from SEVIS and is a strong predictor of numbers that appear in the following year’s Open Doors Report. This year, however, the data between the Fall Snapshot Survey and SEVIS are quite different, though both indicate slowing growth in international enrollment in the U.S.

[6] Central Asia, which includes mostly former Soviet republics in Asia (such as Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan), only accounts for about 1 percent of total enrollment from the overall South and Central Asia region, according to my analysis of IIE Open Doors data.