TL:DR – Key Takeaways

- NotebookLM for Instructional Coaches revolutionizes resource management by allowing coaches to use their specific materials instead of generic AI outputs.

- The tool helps create professional development materials quickly, enabling coaches to synthesize various sources effortlessly.

- NotebookLM offers unique features like audio overviews, video explanations, and infographics, enhancing the way coaches present information.

- Coaches can organize notebooks by purpose, rename their sources for clarity, and customize responses for different audiences.

- Joining communities like GEG helps coaches share strategies and stay updated on innovative practices using NotebookLM.

As an instructional coach, you’re constantly juggling multiple responsibilities—supporting teachers, creating professional development materials, organizing resources, and staying current with educational technology. What if there was a tool that could help you synthesize information, create engaging content, and save hours of prep time? Enter NotebookLM, Google’s AI-powered workspace that’s revolutionizing how coaches work with information.

What Makes NotebookLM Different for Coaches?

Unlike general AI tools like ChatGPT or Gemini that pull from the entire web, NotebookLM gives you complete control over your sources. You choose exactly what information goes in—whether it’s your district’s strategic plan, professional development materials, curriculum documents, or teacher resources—and NotebookLM works exclusively with that content.

This is a game-changer for instructional coaches. You’re not getting generic advice or hallucinated information. You’re getting insights, summaries, and resources based on your specific materials, aligned to your district’s goals, and tailored to your teachers’ needs.

Real-World Applications for Instructional Coaches

Creating PD Materials in Minutes

Imagine this scenario: You’ve gathered resources about implementing Google Workspace tools in the classroom. You have PDFs, website links, video tutorials, and Google Docs with implementation guides. Instead of manually synthesizing all this information, you can upload these sources to NotebookLM and ask it to create a newsletter for teachers, generate a quick-start guide, or develop talking points for your next coaching session.

One coach recently used NotebookLM to record a 40-minute lesson observation, uploaded the audio as a source, and asked it to create professional development slides with detailed presenter notes. The tool generated beautiful, comprehensive slides that captured the key teaching strategies demonstrated in that lesson—all without the coach spending hours creating materials from scratch.

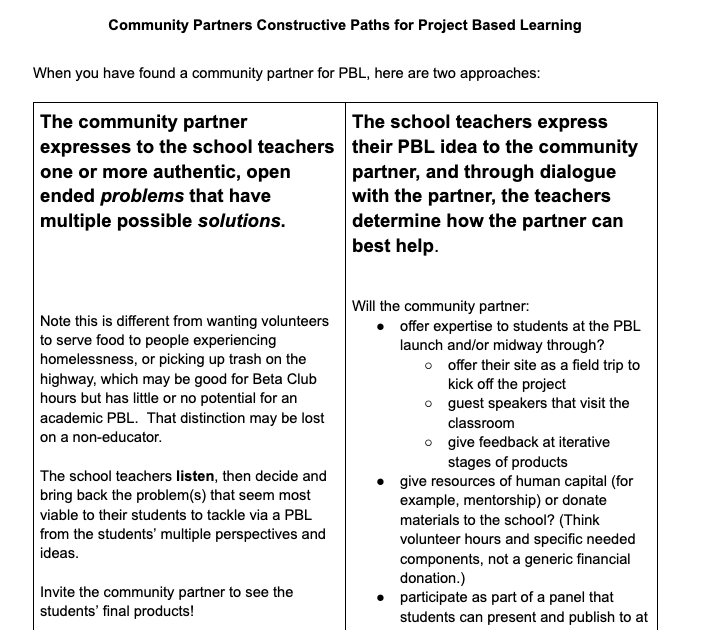

Building Notebooks for School Leaders

Several coaches are now creating custom notebooks for their school leaders that include strategic plans, policy documents, and instructional frameworks. School leaders can then interact with these notebooks to get quick answers, generate reports, or explore connections between different initiatives—all while staying grounded in the district’s actual documents.

Powerful Features That Save Coaches Time

Audio Overviews (The Podcast Feature)

One of NotebookLM’s most popular features creates AI-generated podcast discussions from your sources. Upload your curriculum materials, coaching protocols, or meeting notes, and NotebookLM will generate a conversational audio overview that makes complex information more digestible. These “deep dive” or “brief” options let you control the length and depth—perfect for sharing with busy teachers who prefer audio learning.

Video Overviews with Visual Styles

The newest feature generates explainer videos complete with visuals, making it easier to create engaging PD content. You can choose from multiple visual styles and customize what the video focuses on—ensuring the content stays relevant to your coaching goals rather than pulling in extraneous information.

Infographics and Slide Decks

Need to create professional-looking materials quickly? NotebookLM can generate infographics in landscape, portrait, or square formats, and create slide decks in both detailed and presenter modes. The image generation has improved dramatically, producing visuals that look polished and professional—often better than what many of us could create manually in the same timeframe.

Smart Strategies for Instructional Coaches

Organize by Purpose

Should you create one massive notebook with all your coaching resources, or multiple smaller ones? Most coaches find success with focused notebooks organized by purpose—perhaps one for Google Workspace training, another for literacy coaching, and another for new teacher support. This approach allows you to keep sources relevant and responses targeted.

Rename Your Sources

When you upload documents, rename them to something meaningful for your audience. Instead of “Google_Docs_Editor_Help_Final_v3.pdf,” rename it to “How to Create a Google Doc for Teachers.” This becomes especially important when sharing notebooks with teachers who need to understand what sources are included.

Customize for Your Audience

The new “Configure Chat” feature lets you set how NotebookLM responds. You can create prompts that tell the tool to speak at a second-grade reading level, communicate with teachers who aren’t tech-savvy, or address cabinet-level administrators. This customization ensures the responses match your audience’s needs.

Share Strategically

In education domains, you can share notebooks within your district, either giving full access or chat-only access (with Google Workspace for Education Plus). This makes it easy to create resource hubs that teachers can explore independently, reducing the number of repeat questions you field.

Ready to explore NotebookLM with fellow instructional coaches? Join the Google Educator Group (GEG) for Instructional Coaches—a global community of nearly 500 coaches who share strategies, resources, and support.

Our community hosts monthly meetings, shares practical demonstrations, and provides ongoing support as you implement new tools and strategies in your coaching practice.

Getting Started with NotebookLM

The best way to understand NotebookLM’s potential is to experiment with it. Start small:

- Record a coaching conversation or PD session and upload the audio

- Gather 3-5 documents on a topic you’re currently coaching on

- Upload them to a new notebook and ask NotebookLM to summarize key themes

- Try the audio overview feature to see how it synthesizes your sources

- Share it with a trusted colleague for feedback

Remember, this tool continues to evolve rapidly. Features that launched just weeks ago are already more powerful, and new capabilities are added regularly. The key is to start using it, share what works with your coaching community, and stay curious about new possibilities.

Take Your Coaching Impact Further

As you explore new tools like NotebookLM to enhance your coaching practice, consider diving deeper into frameworks that amplify your impact. My book, Impact Standards, provides actionable strategies for educators and coaches who want to make a lasting difference in their schools and districts.

Want to stay connected and receive regular insights, tools, and strategies for instructional coaching? Subscribe to my newsletter for exclusive tips that will help you continue growing as an educational leader.

The future of instructional coaching involves smart use of AI tools that amplify—not replace—the human connections at the heart of our work. NotebookLM is one more tool in your coaching toolkit, helping you spend less time on content creation and more time on the relationships and conversations that truly transform teaching and learning.

Upgrade Your Teaching Toolkit Today

Get weekly EdTech tips, tool tutorials, and podcast highlights delivered to your inbox. Plus, receive a free chapter from my book Impact Standards when you join.

Discover more from TeacherCast Educational Network

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.