Analyses of fascism too often fixate on its most spectacular expressions: staggering inequality, systemic racism, the militarization of daily life, unbridled corruption, monopolistic control of the media, and the concentration of power in financial and political elites. Fascism thrives on a culture of fear and racial cleansing and the normalization of cruelty, lies, and state violence. Yet what is often overlooked is how culture and education now function as decisive forces in legitimating these authoritarian passions and in eroding democratic commitments. As Hannah Arendt, Jason Stanley, Richard Evans, Chris Hedges, and others remind us, the protean origins of fascism are never fully buried; they return in altered and often disguised forms, seeping into everyday life and reshaping the common sense of a society.

Under US President Donald Trump, we face a terrifying new horizon of authoritarian politics: the erosion of due process, mass abductions, vicious attacks on higher education, and the steady construction of a police state. Canada has not yet descended into such full-fledged authoritarianism, but troubling echoes are undeniable. Public spaces and public goods are under assault, book bans have appeared in Alberta, languages of hate increasingly target those deemed disposable, the mass media bends to corporate interests, labour is suppressed, and democratic values are met with disdain. These may not replicate the worst horrors of the past, but they reveal how culture and education become the terrain upon which democracy is dismantled and authoritarianism gains legitimacy. These are warning signs of a gathering darkness that must be confronted before they harden into something far more sinister.

Culture and Pedagogy

Fascism thrives not only on brute police power, prisons, or economic violence but also on culture and pedagogy. Culture has increasingly become a site in the service of pedagogical tyranny. It works through erasure and repression, through memory stripped of its critical force, and through dissent silenced in the name of order. Fascism is never solely a political or economic system; it is a pedagogical project, a machinery of teaching and unlearning that narrows the horizon of what can be said, imagined, or remembered.

Today authoritarianism seeps insidiously into everyday life, embedded in seemingly obvious maneuvers that consolidate power under the guise of technical or bureaucratic necessity. Its mobilizing passions often emerge unobtrusively in maneuvers that hide in the shadows of the mundane, often at the level of everyday experience.

This creeping logic is starkly visible in Ontario, where Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservative (PC) government has moved to seize control of local school boards. What may look like routine administrative measures should be read as a warning: authoritarianism does not arrive only with grandiose spectacles or open attacks on democracy’s foundations; it gains ground quietly, through the erosion of the ordinary, the capture of the local, and above all, through the weaponization of education as a tool to dismantle democracy itself.

The Ford government’s seizure of the Toronto, Toronto Catholic, Ottawa-Carleton, and Dufferin-Peel Catholic district school boards is extraordinary, even for this democracy-averse regime. Education Minister Paul Calandra has even mused about eliminating trustees altogether before the 2026 local elections, declaring “Everything is on the table.” His justification that Ontario’s Ministry of Education (MOE) has allowed them to make too many decisions on their own is both unsupported and revealing. It exposes a deeper authoritarian project: the desire to centralize power and strip away democratic oversight from institutions closest to local communities. It curbs liberal instincts of trustees who see first-hand the vast diversity of lives and needs of the families who rely on their schools.

This is precisely how authoritarian control operates: by eroding intermediary structures that connect people to power. Just as Donald Trump sought to bend national cultural institutions like the Smithsonian Museum to his will, Ford dismantles the modest democratic functions of trusteeship. Both cases illustrate how authoritarianism works through the fine print of governance as much as through grandiose pronouncements.

Manufactured Deficits and Structural Starvation

The pretext for takeover was financial mismanagement. Yet none of the investigators found evidence of serious fiscal incompetence. The truth is that boards submitted balanced budgets year after year but only after slashing programs and services, closing outdoor education centres, selling property, cutting staff, and raising fees. What really drives their fiscal crises is a decades-old funding model – first imposed by the Mike Harris PC government in 1997 – that shifted resources from local taxes to provincial grants. This was not a move toward equitable funding; these were neoliberals of the first order who believed in central control of funding so they could squeeze school boards and education workers to contain costs.

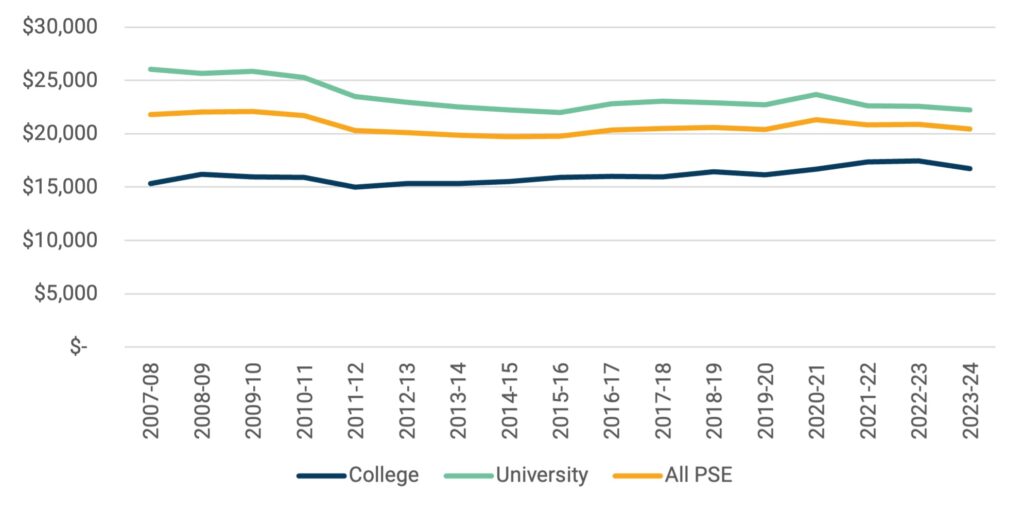

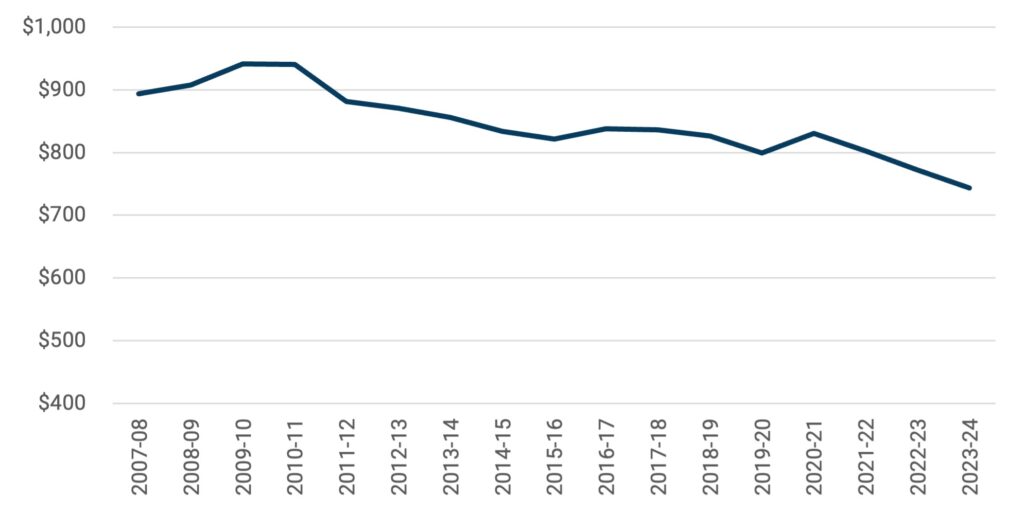

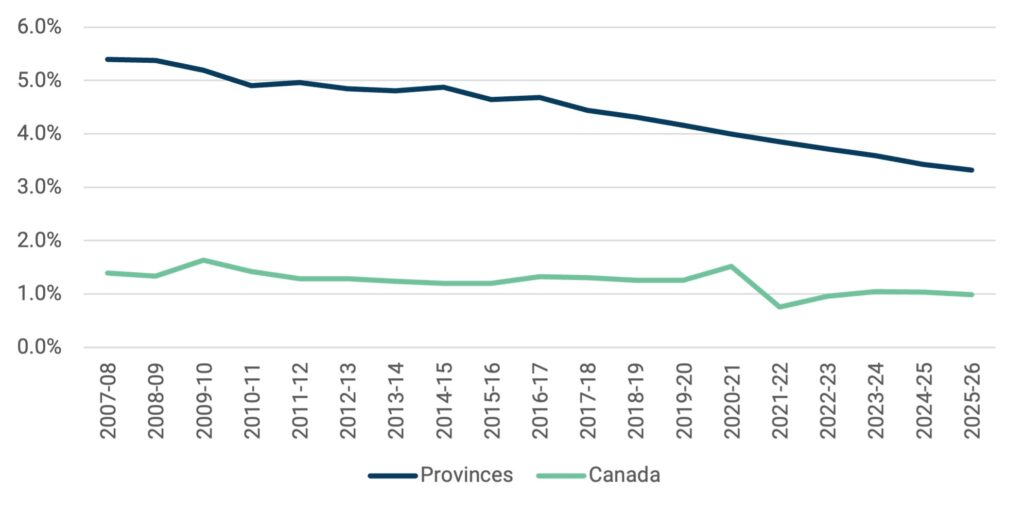

This model, based on enrolment rather than actual need, starved boards of resources for special education, transportation, salaries, and infrastructure. For instance, school boards don’t get funding for actual children who need special education support but rather on the basis of a predictive model MOE devised. Boards pay for the kids MOE doesn’t fund. The Ford government hasn’t funded the full increase for statutory teacher benefits for years, leaving boards short by millions. The result is a structural deficit: chronic underfunding that leaves even well-managed boards teetering on insolvency. The Ford government, while claiming to increase spending, has in fact cut funding per student by $1,500 in real terms since 2018. This is the problem faced by with 40 percent of Ontario school boards.

It is this manufactured insolvency that led Minister Calandra to get the most out of a useful crisis and put the four school boards under supervision and maybe next eliminate all school boards in the province. Here we see neoliberal austerity converging with authoritarian ambition. Underfunding is not a policy mistake; it is a deliberate strategy to weaken public education, undermine trust in democratic institutions, and prepare the ground for privatization schemes such as vouchers and charter schools. In this instance, the policy of underfunding is a way of weakening public education and then blaming whatever problems occur on education itself. This is gangster capitalism at work, cloaked in the language of fiscal responsibility but fueled by a pedagogy of dispossession.

Eliminating Trustees, Silencing Communities

If board takeovers were simply about money, supervisors would have been told to just find savings. Instead, elected trustees were suspended, their offices shuttered, their tiny stipends cut off, and their ability to communicate with constituents forbidden. Calandra’s power grab has all the elements of Elon Musk’s DOGE assaults in the US: move fast, offer absurd excuses, and blame the victims. The supervisors replacing trustees – accountants, lawyers, and former politicians with no background in education – now wield greater power than the elected community representatives they displaced.

This substitution of technocrats for democratically accountable representatives is part of fascism’s pedagogy. It teaches the public to accept disenfranchisement as efficiency, to see obedience as order. Parents who ask why a program disappeared or why their child’s special education class has grown larger are now met with silence. In this vacuum, the lesson learned is that participation is futile and resistance meaningless – precisely the kind of civic numbing oligarchic fascism requires.

Command, Control, and the Policing of Education

Ford’s government frames these takeovers as a “broader rethink” of governance, but the real project is clear: the imposition of command and control over education. This move sends a strong message that it’s time to duck our heads and get back to basics: teaching “reading, writing, spelling, and arithmetic and the whole shebang…” as Doug Ford complained last fall after teachers and students attended a rally in support of the Grassy Narrows First Nation and its efforts to deal with generations of mercury contamination in their area. He proclaimed, with no evidence, that the field trip was “indoctrination” by teachers because activists protesting Israeli genocide were present. Community members who supported an Indigenous curriculum, modern sexual education, or even school-name changes honoring anti-colonial figures are dismissed or painted as obstacles. The message from Ford and Calandra is blunt: stick to the basics – reading, writing, arithmetic – and leave politics at the door.

Yet politics hangs over classrooms like a shroud. Despite his Captain Canada complaints about the Trump tariffs, Ford admires the President quick-marching America toward fascism. In an off-mic moment he commented recently: “Election day, was I happy this guy won? One hundred per cent I was.” It’s not the racism, the authoritarianism, the compulsive lying, the fraud, the sexual assaults that bothers the Premier; it’s that he got stiffed by his friend.

Usurping trustees according to University of Ottawa professor Sachin Maharaj is just another step toward the Progressive Conservatives’ goal to “squelch the pipeline of more progressive leaders” like those gaining notice and experience attending to the needs of local schools.

The banning of the Toronto Muslim Student Alliance’s screening of the film No Other Land, which documents Israeli settler violence, shows how censorship now masquerades as neutrality. This is the pedagogy of repression in action: narrowing what can be taught, remembered, or discussed until education is reduced to obedience training. What parades as a “broader rethink” is part of the authoritarian language of censorship and control. Like Trump’s attacks on “critical race theory” or his censorship of the Smithsonian, Ford’s moves are not about protecting students from politics but about protecting power from critique. The real issue here is constructing authoritarian policies that narrow critical thinking, teacher autonomy, essential funding, and knowledge that enable schools to both defend and facilitate democracy.

For Ford and his adherents, the real issue is not that schools are failing but that they are public and have a vital role to play in a democracy. The real threat to Ford is that a democracy can only exist with informed citizens. Yet that is precisely the role education should assume.

Bill 33: Codifying Authoritarianism

The perversely named Bill 33, the Supporting Children and Students Act extends this authoritarian logic. It allows the Minister to investigate boards or trustees on the mere suspicion they might act “inappropriately” or against the “public interest” – an elastic phrase that grants unchecked power. It checks much-maligned Diversity Equity and Inclusion efforts by refusing boards the right to name schools, forcing them to abandon diversity-affirming figures in favor of colonial or sanitized names. It mandates the reintroduction of police officers into schools, despite community opposition to surveillance and “unaccountable access to youth by cops.”

At work here is the legacy of colonialism, a legacy that is terrified of diversity, of those deemed other, being able to narrate themselves. Viewed as threat, this anti-democratic language ultimately falls back on issues of control and security. This is one instance of how authoritarianism consolidates itself, not through tanks in the streets but through legislation that transforms education into an arm of the security state. Pedagogical spaces are militarized, memory is policed, and students are taught that surveillance is normal and dissent dangerous.

Trumpasitic Authoritarianism

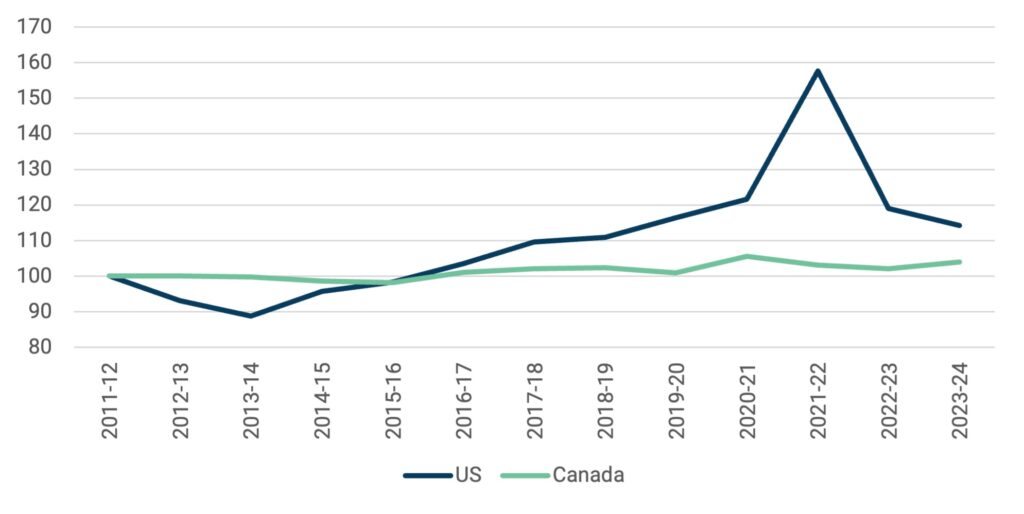

Ford’s methods echo those of his southern counterpart. Just as Trump’s politics thrive on dispossession, erasure, and the weaponization of culture, Ford borrows from the same authoritarian playbook. The takeover of school boards not only tightens political control but also grants easy access to billions of dollars in public land, enriching developers tied to his government. Here, neoliberal profiteering fuses seamlessly with authoritarian centralization, an example of the merging of gangster capitalism with the pedagogy of repression.

What do you expect from a government that makes decisions reflecting the arrogance of power? The Ford government cut Toronto city council in half soon after took office in 2018 and threatened to use a constitutional override, the Notwithstanding Clause, Section 33 of Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms, to overturn a Superior Court justice’s decision that the move was unconstitutional. Ford actually used the clause to push through a bill restricting election advertising in 2021 and again, pre-emptively, in 2022, buttressing back-to-work legislation against striking public workers, among the lowest paid in the province. He’s considering using it again after his decision to remove bike lanes from Toronto streets was overturned in court; power makes you petty.

Democracy in the Smallest Details

The takeover of Ontario school boards may appear less dramatic than Trump’s assaults on national institutions, but its implications are just as dire. Authoritarianism advances not only through spectacle but through the slow erosion of local democratic practices that once seemed secure.

If fascism is a pedagogy of fear, amnesia, and conformity, then resistance must be a pedagogy of memory, solidarity, and imagination. To defend education is to defend democracy itself, for schools are not simply sites of instruction but laboratories of citizenship, places where young people learn what it means to speak, to question, to remember, and to act. When trustees are silenced, when curricula are censored, when communities are stripped of their voice, what is lost is not only oversight but the very possibility of democratic life.

What is at stake, then, is far larger than budget shortfalls or bureaucratic reshuffling. It is whether the future will be governed by communities or dictated from above by those who mistake obedience for learning and silence for peace. Fascism thrives in these small erasures, in the details that seem technical until they harden into structures of domination.

The lesson could not be clearer: democracy dies in increments, but it can also be rebuilt in increments – through collective memory, through civic courage, through the refusal to allow education to become a weapon of obedience. To resist the Ford government’s authoritarian incursions is not only to protect local school boards; it is to reclaim the very ground on which democratic hope stands. •

Henry A. Giroux currently is the McMaster University Professor for Scholarship in the Public Interest and The Paulo Freire Distinguished Scholar in Critical Pedagogy. His most recent books include The Violence of Organized Forgetting (City Lights, 2014), Dangerous Thinking in the Age of the New Authoritarianism (Routledge, 2015), coauthored with Brad Evans, Disposable Futures: The Seduction of Violence in the Age of Spectacle (City Lights, 2015), and America at War with Itself (City Lights, 2016). His website is henryagiroux.com.

William Paul is editor of School Magazine website.

This article first appeared at the Social Project Bullet