by Savannah Celeste Scott, The Hechinger Report

November 17, 2025

Imagine clocking out of an eight-hour shift and your compensation is a pat on the back and experience for your resume.

This scenario is a disturbing reality for around one million college students, and it needs to stop. Students work countless hours on top of their academic pursuits only to be told they should be “grateful for the opportunity.”

The government must pass legislation mandating that all internships include monetary compensation; employers must stop exploiting students and recent graduates while they build necessary work experience.

The idea of an unpaid internship is odd considering that most of us grew up learning that work is rewarded. Some 71 percent of American households give children ages 5 to 17 an allowance for doing their chores, a Wells Fargo study found.

Practices like that have led many of us to believe that labor should be paid, and it should be no different when we enter the job market.

Related: Interested in innovations in higher education? Subscribe to our free biweekly higher education newsletter.

There is a disturbing correlation between unpaid internships and exploitation, especially for people from marginalized communities. Historically, Black people have been the face of working without compensation — a phenomenon dating back to early American slave practices.

Unpaid work is not just exploitation — it is dehumanizing. No person can survive without money, so no one should be required to work with no compensation to help them live. The reality is that, unlike higher-income students, low-income students cannot afford to work for free. They need money to cover their tuition, afford groceries and pay for a place to live. This is why unpaid internships further the cycle of economic exploitation, the student-run Columbia Spectator noted.

Yet there are plenty of people who believe compensation does not always have to be monetary. Many students have heard employers extol the value of “experience” as they try to persuade them to work without pay.

Such was the case for me when I was hired for a legal internship as a freshman in college. I thoroughly enjoyed my internship, as it gave me both professional and social opportunities. But it was an extremely difficult time for me both mentally and financially.

I was taking 16 credit hours, regularly writing for a student publication and working another part-time job to save money for law school. The stress of going into the office every day to handle casework — often ranging from domestic violence to sexual assault cases — was mentally taxing when combined with schoolwork and extracurricular responsibilities.

While the experience that the internship provided was incredible, monetary compensation would have made it much less stressful, as I would not have needed the other job.

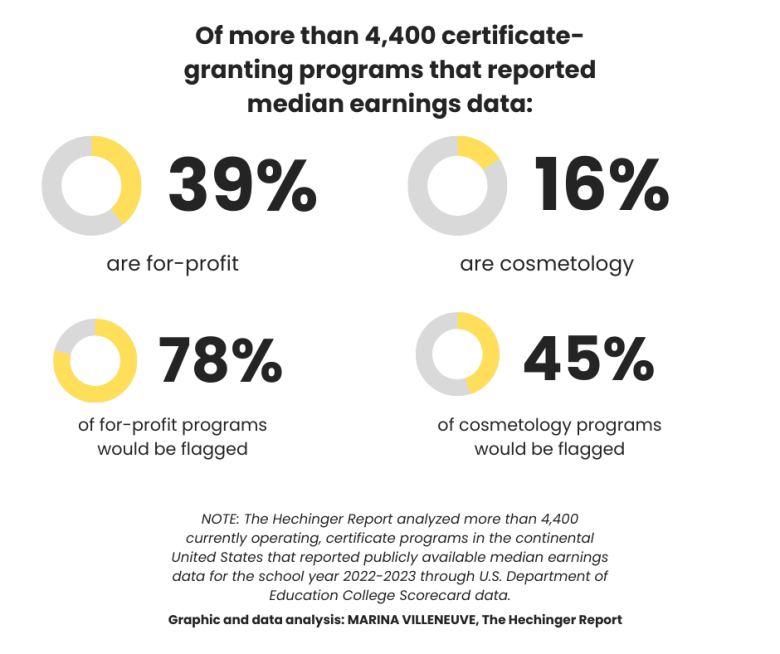

Unpaid internships can also hurt graduates’ prospects in the job market. Those who have had unpaid internships receive fewer job offers on average than those who completed paid internships, statistics from the National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE) show.

The average student who completed an unpaid internship also saw $22,500 less in their starting salaries than those who completed paid internships. According to the Delta Institute, “employers offering compensation tend to invest more in mentoring, performance feedback, and skill-building”; that added investment provides students with more preparation for the job market and helps them look more impressive to an employer.

Related: Looking for internships? They are in short supply

Unpaid interns have been fighting for compensation for decades. A lawsuit filed by two interns against Fox Searchlight over their lack of compensation when working on the movie “Black Swan” resulted in a legal battle that lasted five years. The two interns were finally compensated a total of $13,500 for their work — despite the film grossing more than $300 million.

The Fox Searchlight lawsuit sparked a wave of other impassioned interns to plead their cases as well, including a class-action lawsuit against NBCUniversal back in July 2013. That resulted in a $6.4 million settlement split among thousands of interns.

In both cases, the employers made millions of dollars in profits but still refused to pay their interns until they were legally forced to do so.

According to Shawn VanDerziel, the president and chief executive officer of NACE, paid internships are a “game changer” to employers and employees alike. The dilemma is this: Employers want labor, and students want internships. The most obvious solution would be to pay students for the work that they do.

Students do not work for fun. They work because they want to create better futures for themselves; their success will be less likely if they don’t receive monetary compensation. The government needs to make it illegal for employers to exploit students by having them work without pay.

College students should not be expected to work for free.

Savannah Celeste Scott is a senior at the University of Georgia in Athens, studying journalism, Spanish and law, jurisprudence and the state on a pre-law track.

Contact the opinion editor at [email protected].

This story about unpaid internships was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’s weekly newsletter.

This <a target=”_blank” href=”https://hechingerreport.org/student-voice-college-students-are-tired-of-being-told-that-we-should-be-grateful-for-our-internships-we-also-want-to-get-paid/”>article</a> first appeared on <a target=”_blank” href=”https://hechingerreport.org”>The Hechinger Report</a> and is republished here under a <a target=”_blank” href=”https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/”>Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License</a>.<img src=”https://i0.wp.com/hechingerreport.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/cropped-favicon.jpg?fit=150%2C150&ssl=1″ style=”width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;”>

<img id=”republication-tracker-tool-source” src=”https://hechingerreport.org/?republication-pixel=true&post=113342&ga4=G-03KPHXDF3H” style=”width:1px;height:1px;”><script> PARSELY = { autotrack: false, onload: function() { PARSELY.beacon.trackPageView({ url: “https://hechingerreport.org/student-voice-college-students-are-tired-of-being-told-that-we-should-be-grateful-for-our-internships-we-also-want-to-get-paid/”, urlref: window.location.href }); } } </script> <script id=”parsely-cfg” src=”//cdn.parsely.com/keys/hechingerreport.org/p.js”></script>