by Julie Burrell | March 12, 2024

Since 1996, the National Committee on Pay Equity has acknowledged Equal Pay Day to bring awareness to the gap between men’s and women’s wages. This year, Equal Pay Day is March 12 — symbolizing how far into the year women must work to be paid what men were paid in the previous year.

To help higher ed leaders understand, communicate and address gender pay equity in higher education, CUPA-HR has analyzed its annual workforce data to establish Higher Education Equal Pay Days for 2024. Tailored to the higher ed workforce, these dates observe the gender pay gap by marking how long into 2024 women in higher ed must work to make what White men earned the previous year.

Higher Education Equal Pay Day fell on March 5, 2024, for women overall, which means that women employees in higher education worked for more than two months into this year to gain parity with their White male colleagues. Women in the higher ed workforce make on average just 82 cents for every dollar a White male employed in higher ed makes.

Highlighting some positive momentum during this Women’s History Month, some groups of women are closer to gaining pay equity. Asian American women in higher ed worked two weeks into this year to achieve parity on January 14 — not ideal, but by no means insignificant. In fact, during the academic year 2022-23, Asian American women administrators in particular saw better pay equity than most other groups, according to CUPA-HR’s analysis.

But the gender pay gap remains for most women, and particularly for women of color. Here’s the breakdown of the gender pay gap in the higher ed workforce, and the Higher Education Equal Pay Day for each group.* These dates remind us of the work we have ahead.

- March 5 — Women in Higher Education Equal Pay Day. On average, women employees in higher education are paid 82 cents on the dollar.

- January 14 — Asian Women in Higher Education Equal Pay Day. Asian women in higher ed are paid 96 cents on the dollar.

- March 1 — White Women in Higher Education Equal Pay Day. White women in higher ed are paid 83 cents on the dollar.

- March 12 — Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander Women in Higher Education Equal Pay Day. Native of Hawaii or Pacific Islander women in higher ed are paid 80 cents on the dollar.

- March 28 — Black Women in Higher Education Equal Pay Day. Black women in higher ed are paid 76 cents on the dollar.

- April 12 — Hispanic/Latina Women in Higher Education Equal Pay Day. Hispanic/Latina women in higher ed are paid 72 cents on the dollar.

- April 22 — Native American/Alaska Native Women in Higher Education Equal Pay Day. Native American/Alaska Native women are paid just 69 cents on the dollar.

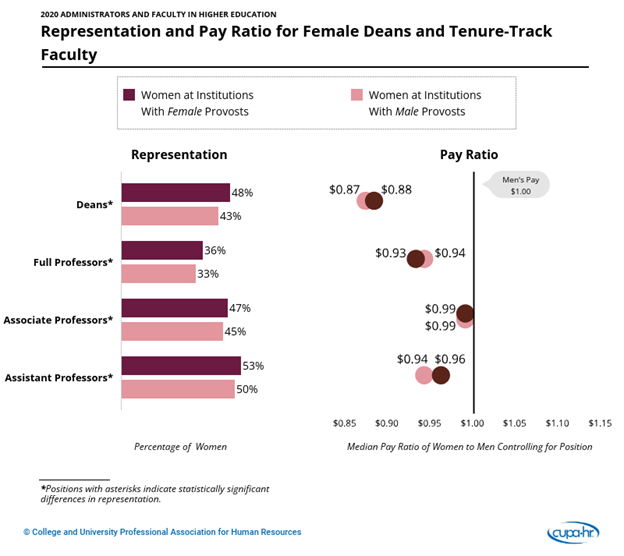

CUPA-HR research shows that pay disparities exist across employment sectors in higher ed — administrators, faculty, professionals and staff — even as the representation of women and people of color has steadily increased. But with voluntary turnover rising, not addressing pay disparities could be costly.

CUPA-HR Resources for Higher Education Equal Pay Days

As we observe Women’s History Month and Higher Education Equal Pay Days for women, we’re reminded that the fight for equal pay is far from over. But data-driven analysis with the assistance of CUPA-HR research can empower your fight for a more equitable future.

See our interactive graphics that track gender and racial composition, as well as pay, of administrative, faculty, professional, and staff roles, collected from CUPA-HR’s signature surveys:

*Data Source: 2023-24 CUPA-HR Administrators, Faculty, Professionals, and Staff in Higher Education Surveys. Drawn from 633,020 men and women for whom race/ethnicity was known.