A language is not merely a collection of words; it is a symphony of memories, a melody that holds the heartbeat of a nation. It is a living chronicle of history, breathed across the ages, inscribed on the rhythms of life and sung by the winds that dance upon the sacred lands.

Picture a serene village cradled among ancient mountains, where elders speak a tongue as timeless as the rocks beneath their feet. Each syllable is a thread, knitted into a rich tapestry of legends, lore and traditions that bind them to the soil they call home.

But what becomes of this language when the land itself starts to crumble? When the waves rise to consume coasts, or parched earth splits under a blistering sun, does the song fall silent? Today, as the planet warms, it is not only ice caps and forests that vanish — but languages, and with them, entire ways of perceiving the world.

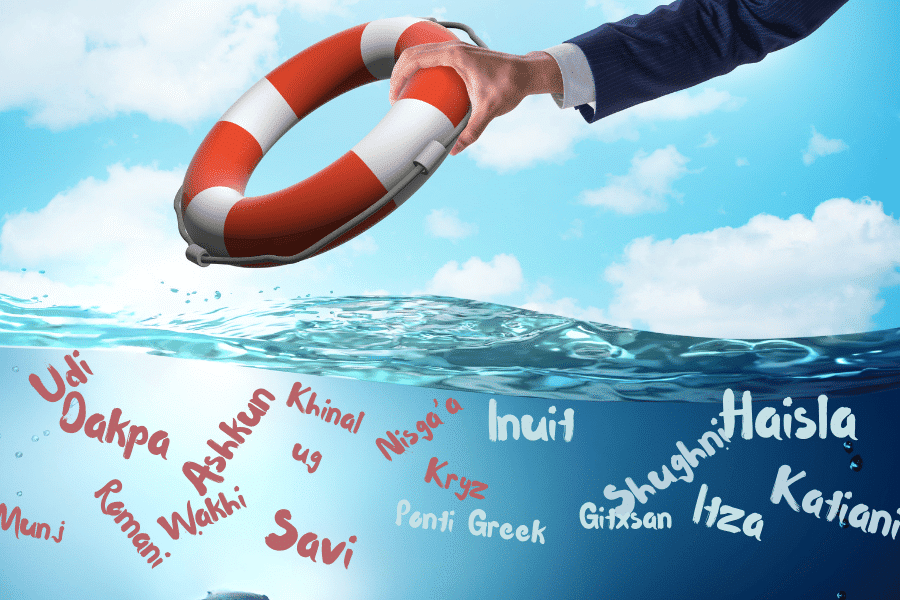

Around the globe, ancient languages — the essence of human history — are vanishing. Climate change, a tenacious force reshaping landscapes, frays the delicate cultural threads that root communities to their identity. Rising seas engulf islands where indigenous tongues blossom like rare flowers. Wildfires sweep away more than homes, reducing sacred spaces and oral histories to ash. Each vanished habitat is a stilled voice, an erased library of metaphors, idioms and songs that offered a unique lens on life.

Language extinction

According to a 2021 report by the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, more than 40% of the world’s estimated 7,000 languages are at risk of disappearing. “When a language dies,” said linguist K. David Harrison, “a unique vision of the world is lost.”

While globalisation and modernisation are often blamed for the erosion of ancient languages, environmental destruction plays an even more insidious role, quietly displacing communities and severing their linguistic roots. When climatic disasters scatter people, they do not only lose their home — they lose the vessel of their shared soul. Dispersed and assimilating, their words, their tales, their melodies — once carried across centuries — fade into echoes long forgotten.

Today, nearly half of all languages spoken globally are endangered. According to UNESCO, one language disappears every two weeks — a rhythm of loss as steady as the ticking of a clock. In this tide of vanishing voices, climate change surges as an unrecognised adversary, disrupting the habitats where these languages are rooted.

Consider the small island nations of the Pacific — Tuvalu, Kiribati, the Marshall Islands — where languages are inseparable from the ocean’s ebb and flow. As seas rise up to threaten these vulnerable islands, the inhabitants must depart, and with them, their distinct vision of the world drifts away. Words that once named the tides, the winds, the colour of the sky before monsoon, these vanish as the speakers are displaced.

Likewise, in the Arctic, the Sámi and Inuit communities confront an ugly truth: their languages, like their frozen lands, are melting under the pressure of a warming world. The vocabulary used to describe different types of snow, hunting rituals or the behaviour of migrating herds holds ancestral wisdom. As the landscape changes, the words that once matched its rhythms no longer apply — and are slowly lost.

Worldviews and wisdom

When languages are lost, they take with them entire worldviews and centuries of wisdom encoded in words. The knowledge of forests, of skies, of seas — how to farm to the beat of nature, how to heal using the plants that grow in secret groves — is lost.

For instance, in the Amazon rainforest, indigenous languages such as Kayapo contain the secrets of life-abundant ecosystems. According to Survival International and linguistic researchers, these languages encode unique ecological wisdom that cannot be translated. Each word is a secret to decoding the harmony of nature and each lost language shelves an irreplaceable piece of the puzzle.

In the Philippines, the Agta people hold oral traditions that teach sustainable fishing and forest stewardship. Their language contains knowledge passed down through chants and stories that teach children when to harvest, what to leave behind and how to give back. Without their land, without their rituals, such teachings dissolve.

In Vanuatu, where the rising tide of the ocean promises to wash away land and language, communities are in a mad dash to record their heritage. Elders and linguists collaborate, transcribing words into digital platforms, preserving the poetry of their world for future generations. Stories once passed from mouth to ear around firelight are now finding their way into apps, audio archives and cloud storage — fragile vessels carrying ancient truths.

A fading past and uncertain future

Technology, too, becomes a bridge between the fading past and an uncertain future. Apps like Duolingo and platforms like Google’s Endangered Languages Project breathe new life into ancient words, making them accessible to the young and curious.

Augmented reality and virtual storytelling spaces are beginning to preserve not just the language, but the experience of being immersed in it. But technology alone cannot carry the weight of this preservation. It must be paired with policies that protect the vulnerable — giving displaced communities a voice not only in language preservation but in shaping climate action itself.

Governments must go beyond digitisation and invest in cultural resilience. Language must be taught in schools, inscribed in constitutions, spoken on airwaves and celebrated in ceremonies. We need climate policies that understand that saving ecosystems and saving languages are part of the same struggle. Both are about preserving what makes us human.

In the end, saving a language is an act of defiance against the erasure of identity. It is a way to honour the past while forging a path to a sustainable future. These languages do not merely recount history — they carry the wisdom of living in harmony with the Earth. In their poetry and proverbs, in their songs and silences, they have answers to questions we have not even thought to ask yet.

To preserve these voices, we must become their echoes. We must act before it’s too late. Before the last storytellers fall silent. Before the rivers can no longer remember the songs they once inspired. To save a language is to save a piece of ourselves — the spirit of who we are, where we’ve been and the dreams of where we might go.

When we lose a language, we don’t just lose words — we lose the Earth’s voice itself. If these voices vanish, who will remember the names of the stars? Who will tell us how the mountains mourned or the forests sang? The Earth is listening and its languages are calling.

Let us not forget how to answer.

Questions to consider:

1. Why are languages at risk of extinction due to climate change?

2. How are preservation of language connected to whole cultures?

3. Why might someone want to master a language that is not widely spoken?