by Katherine Friend and Aisling Walters

When we write about creativity, we often refer to the work of geniuses; [distancing] ordinary members of society from the act of creativity by reinforcing a perception that they could never be creative themselves (Dymoke, 2020: 80).

The state of creativity

The damage wrought by the stereotype of a creative as an isolated genius seems likely to increase within the current context of the UK school system, where an overloaded curriculum and assessment driven pedagogies dominate. The 2023 State of Creativity report notes that creativity has been ‘all but expunged from the school curriculum in England’. Educators across schools and departments in HEIs are attempting to resist the current educational practice which promotes students as consumers and centres our students as active producers in their own learning. Yet, as education policy from primary through to higher education continues not only to cut its emphasis on the humanities and creativity, but also eliminate arts and humanities departments altogether, higher education runs a profound risk of further alienating students from the benefits of creative thinking and artistic practice.

Our undergraduates, being educationalists, use sociological and psychological lenses to understand the social and cultural landscape affecting both classroom learning and community education more broadly. Nevertheless, despite education being at the intersection of many academic disciplines (Sociology, English, Philosophy, History to name a few), students are often reluctant to incorporate alternative approaches into their learning and even less so into their assessments.

Fear and discomfort

As educators, we ask students to embrace discomfort when learning different theoretical approaches or understanding alternative viewpoints. But often, we do not ask them to embrace discomfort in operating outside of the neoliberal HE system, a ‘results driven quantification [which] directs learning’ (Kulz, 2017 p. 55). Within this context, learning focuses on the product (the assessable outcome), rather than the process (the learning journey). Thus, it is unsurprising that our undergraduates initially baulked at the idea of an assessment that incorporated a creative element, preferring essays and multiple-choice exams instead. Hunter & Frawley (2023) define arts-based pedagogy (ABP) as a process by which students can observe and reflect on an art form to link different disciplines, thus encouraging students to lean into uncomfortable subject matter and explore their place within in the wider world. To build more dynamic and critically analytical students, we had to simultaneously encourage an ABP approach so they would understand their academic and theoretical course content more fully while scaffolding their learning through a series of creative activities designed to engage students with different forms of learning and reflection. By incorporating cultural visits, mentorship, and creative assessments into the module, art enhanced subject teaching while encouraging students to think more deeply about their own practice (Fleming, 2012). Yet, incorporating practice was not enough, we were faced with the question: how do educationalists ask students to engage with their vulnerabilities around creative practice (the belief and the engrained fear that they cannot do art or are not good at art) and lead them to an understanding that vulnerability itself can be beneficial?

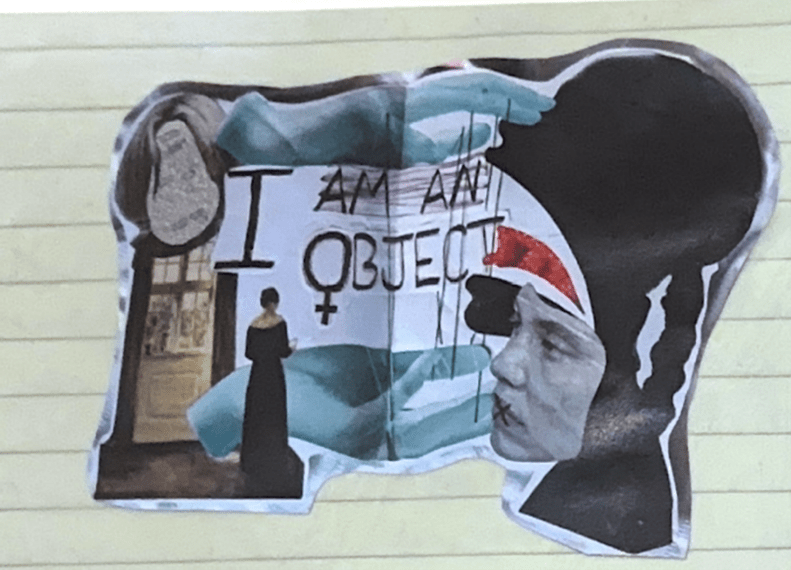

Perhaps, the most basic answer came by asking ourselves, are we, as academics, scared of implementing creative pedagogies because we are scared of showing our own vulnerabilities? What if we as educators fail at a task and our students see? What would happen if we became vulnerable alongside our students? Jordan (2010) argues that when vulnerability is met with criticism, we disengage as a self-preservation tactic. For Brown, acknowledging our insecurities offers a means of understanding ourselves, developing shame resilience and acting authentically. In our session, our vulnerability as lecturers was tested when engaging with textile art, specifically a battle with crochet. Our students saw educators who were not secure or competent in a task. This resulted in a small amount of mockery, but also empathy and offers of support. By stepping out of our comfort zone and embracing a pedagogy of discomfort (Boler 1999), we encouraged our students to challenge themselves. Romney and Holland (2023) refer to this as a ‘paradox of vulnerability’: by overcoming our own reluctance to be vulnerable with our learners we create connections and a sense of trust. We should add that the session explored women’s textile art as activism and the outcome, a piece of textile art, symbolically woven together by students and staff—all female.

Importance of community and connection

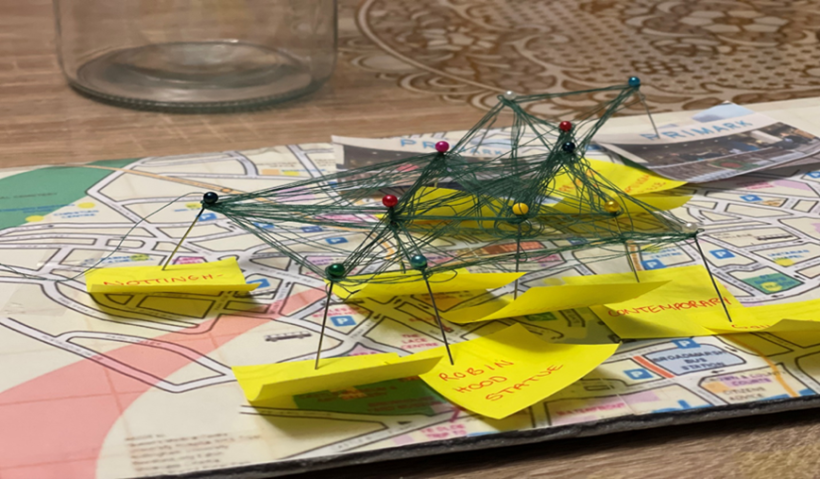

Once we examined theoretical and personal aspects of discomfort and vulnerability, to support and enhance our focus on creative practice, we drew on local cultural partnerships. The incorporation of cultural visits, mentorship from resident artists, and creative exercises enriched our subject teaching while simultaneously encouraging students to think more deeply about their own practice (Fleming, 2012). It also built an alliance between social scientists and colleagues in arts and humanities disciplines, capitalising on their expertise and years of honing ABP. Nottingham is a city where the legend of Robin Hood, outlaws, and rebellion intersect with vibrant cultural community. But many of our students do not engage with cultural spaces, leading to double disconnect, first from their own creative practice and second from the cultural sector altogether. Our students expressed their disconnect from the cultural heart of Nottingham was due to the spaces being ‘not for them’ or a worry that they would not ‘understand’ the art. By exploring the city centre as a group, walking from one site to another, we broke down barriers around these prohibited spaces.

Once inside the Nottingham Contemporary, the resident artists told their own stories of fear, worries of judgement, and expressed anxieties of creative practice, thus setting our students free from the myth of the genius artist – untouchable by self-doubt. This realisation allowed our students to relax and engage worry-free into the creative tasks.

By joining in with these activities, lecturers and students learned alongside each other, tackling our insecurities regarding our creative abilities together as a learning community. Perhaps community was the most important outcome in the project as connection was central. Exposure to the cultural sites created a feeling of connection with the cultural heart of the city. Students also, perhaps more importantly, reported that they became more connected to an understanding of themselves as creatives, becoming more autonomous and engaged in their own learning.

Perhaps it is most appropriate to end this post with the voice of one of our year-two students—the transcript from a podcast created as part of her larger portfolio. She asserts:

Art in education is a goldmine of untouched opportunities [and can be] used to foster students’ holistic development, stimulate creative thinking and engagement with social justice. … and to my fellow Artivists, embrace creativity one canvas at a time.

Katherine Friend is an Associate Professor of Higher Education at Nottingham Trent University. Her work focuses on three themes: the underrepresented student experience on university campuses, the importance of undergraduate engagement in the cultural sector, and reconciling international and academic identities. Threading all three themes together are discussions of one’s ‘place’ and/or ‘space’ in HE and how social and cultural hierarchies contribute to identity, representation, and belonging.

Aisling Walters is a Senior Lecturer in Secondary Education at Nottingham Trent University whose research focuses on the development of writer identity in trainee English teachers, preservice teachers’ experiences of prescriptive schemes of learning, arts-based pedagogies, and students as writers.