When Linda Zaugg’s baby caught a high fever in January, it took an hour and a half to walk him to the hospital — a journey that usually takes 10 minutes. But this was Davos, Switzerland during the week of the World Economic Forum (WEF). Some 3,000 politicians and business leaders from all around the world had descended on the city to discuss important political and economic issues.

Zaugg is a member of the local parliament in Davos, a town in the Swiss Alps with a permanent population of about 11,000 people. She has been spearheading a campaign to raise awareness of the local impacts the conference has and find ways to mitigate them.

During the forum, traffic becomes so bad, she said, that ambulances have trouble finding their way through the streets of Davos, causing response times to increase significantly.

Traffic isn’t the only problem. During this time Davos experiences a massive influx of people, causing rent prices to explode by up to 10 times.

“This is the real problem with the WEF,” she said. “Not the conference itself, but all the people and companies that come along with it to make money and advertise.”

Economic effects of an economic forum

Albert Kruker, the tourism director of Davos, warned that these price increases may cause a price spiral which would affect the town year-round.

During the forum, local businesses go into overdrive trying to supply the politicians, journalists and other attendees with everything they require. When asked about it, the owner of a local bakery, Bäckerei Weber, said that it is one of the most profitable but also intense weeks of the year.

“During the conference you get all these catering companies coming in and the hotels are full, so we have a lot more orders,” he told us. “During the conference we work 24 hours a day. Because of the security, we usually start delivering at two o’clock in the morning.”

Many other business and house owners during this time either stock up on their goods or rent out their buildings for exorbitant prices. A banker living in Zurich with an apartment in Davos said that he can rent out his apartment for a single week during the conference for approximately three months’ rent.

In an apartment block right next to the conference hall, many inhabitants move out during the week. These apartments are then rented by journalists, attendees and large companies.

Disruption in Davos

One resident of an apartment block told us that he is never home during the WEF. “I rent out my apartment and go on holiday during this time,” he said.

The housing crunch during the forum is so intense that to accommodate attendees, some renters and families are forced out of their homes for the duration of the conference.

Zaugg said that some landlords even include a clause in the renter’s agreement dictating that the renters must leave during this period. A side effect of this is that many children must live temporarily outside the city and cannot attend school.

This problem is worsened by the fact that the streets are constantly congested and filled with drivers that aren’t used to Davos.

These drivers often do not respect speed limits or pedestrian only zones, requiring even more attention by commuters, which is especially difficult and dangerous for children and the elderly as they aren’t used to this amount of traffic.

Additionally, the public transportation system is bogged down during this time, once again causing confusion among society’s most vulnerable.

Crowds and congestion

Stephan Büchli, a local bus driver, said that there are no fixed schedules during this time as the traffic is simply too unpredictable. Additionally, they must use smaller buses, as the streets are too congested to allow the manoeuvring of the traditional ones.

Furthermore, the new drivers often also park in restricted zones, further impacting public transport.

“Last year I saw an old man at the local bus station during the conference. He was crying very heavily and was confused. It really made me angry,” Zaugg told us.

The level of congestion also brings other problems with it.

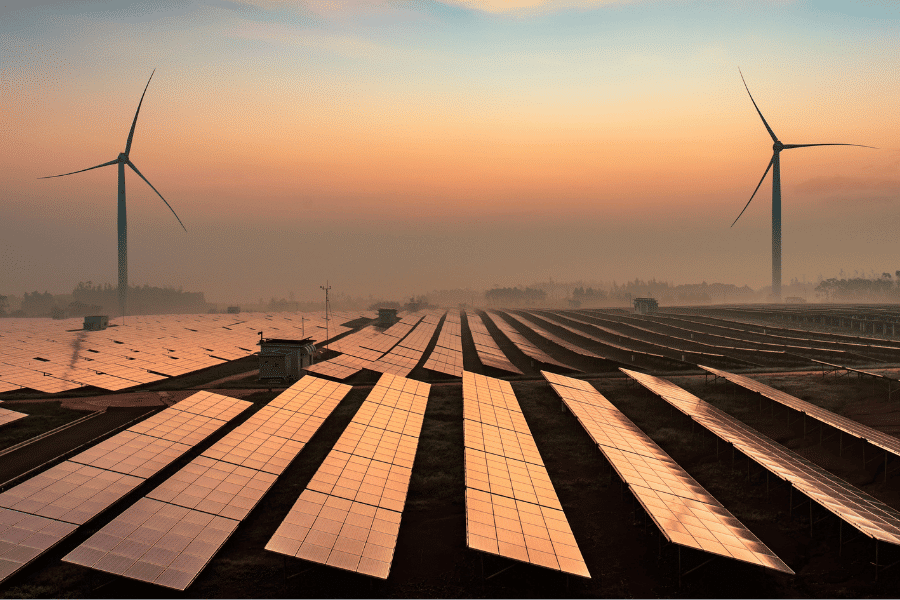

All this traffic creates substantial emissions. In 2023, the private jets attending the Forum alone generated 7,500 tons of CO2, roughly equivalent to the yearly emissions of 5,000 cars.

Minimising the carbon footprint

Part of the problem, Büchli said, is that limousines, trucks and taxis often leave their engines on while standing still, sometimes for upwards of half an hour. He himself has frequently witnessed cars idling with the engine running while stuck in traffic.

As a high-profile event, the WEF requires a lot of temporary structures, internal furnishings and food to function. Every year these temporary structures are erected in late December and then taken down again afterwards. Some of them only get used once and thrown away after only one week’s use.

The same is true for internal furniture such as carpets, shelves, computers and TV screens, as well as any leftover food. Several residents told us that after the WEF there are heaps of electronic equipment that gets thrown away.

Still, while many residents feel the effects, many keep their irritation to themselves out of fear of being labelled a WEF hater.

While there are several key problems with the Forum in its current form, the organisers aren’t sitting idle. Over the past few years, several steps have been taken to lessen the impact of these problems.

The road ahead

The most obvious of these steps is the reduction in waste. The organisers of the conference and the government of Davos have issued regulations on the number of temporary structures and their reusability. This has caused their number to noticeably decrease over the last few editions.

Old furniture and electronic devices are sold to the local inhabitants at reduced prices and spare food is offered to the residents for free, further contributing to making the WEF more sustainable.

To ensure that people can travel around in a manageable timeframe, the municipality has also set up extra trains that commute from one end of the town to the other. Entry into Davos by car was also restricted this year for visitors and tourists.

One of the most impactful changes was the installation of temporary ambulance stations. These stations are scattered across Davos, allowing them to respond quickly to emergencies and save lives.

Over the last few years, both the WEF organisation and Davos itself have taken several different measures to lessen the negative impacts of the conference. However, these issues still persist and require solutions.

Only time will tell if the people who organize a conference meant to bring people together to improve the state of the world can improve the lives of the people who live in this small town in the Alps, for one week of the year.

“You truly notice how the ideological part of the WEF, the bringing together of people, gets pushed into the background in favour of economic reasons,” Zaugg said.

Questions to consider:

1. What is the World Economic Forum?

2. In what ways is the town of Davos negatively affected by the WEF?

3. Is there an event that disrupts life near where you live? How do people deal with it?