EdTech seems to go through perpetual cycles of infatuation and disappointment with some new version of a personalized one-on-one tutor available to every learner everywhere. The recent strides in generative AI give me hope that the goal may finally be within reach this time. That said, I see the same sloppiness that marred so many EdTech infatuation moments. The concrete is being poured on educational applications that use a very powerful yet inherently unpredictable technology in education. We will build on a faulty foundation if we get it wrong now.

I’ve seen this happen countless times before, both with individual applications and with entire application categories. For example, one reason we don’t get a lot of good data from publisher courseware and homework platforms is that many of them were simply not designed with learning analytics in mind. As hard as that is to believe, the last question we seem to ask when building a new EdTech application is “How will we know if it works?” Having failed to consider that question when building the early versions of their applications, publishers have had a difficult time solving for it later.

In this post, I propose a programmatic, sector-wide approach to the challenge of building a solid foundation for AI tutors, balancing needs for speed, scalability, and safety.

The temptation

Before we get to the details, it’s worth considering why the idea of an AI tutor can be so alluring. I have always believed that education is primal. It’s hard-wired into humans. Not just learning but teaching. Our species should have been called homo docens. In a recent keynote on AI and durable skills, I argued that our tendency to teach and learn from each other through communications and transportation technologies formed the engine of human civilization’s advancement. That’s why so many of us have a memory of a great teacher who had a huge impact on our lives. It’s why the best longitudinal study we have, conducted by Gallup and Purdue University, provides empirical evidence that having one college professor who made us excited about learning can improve our lives across a wide range of outcomes, from economic prosperity to physical and mental health to our social lives. And it’s probably why the Khans’ video gives me chills:

Check your own emotions right now. Did you have a visceral reaction to the video? I did.

Unfortunately, one small demonstration does not prove we have reached the goal. The Khanmingo AI tutor pilot has uncovered a number of problems, including factual errors like incorrect math and flawed tutoring. (Kudos to Khan Academy for being open about their state of progress by the way.)

We have not yet achieved that magical robot tutor. How do we get there? And how will we know that we’ve arrived?

Start with data scientists, but don’t stop there

As I read some of the early literature, I see an all-too-familiar pattern: technologists build the platforms, data scientists decide which data are important to capture, and they consult learning designers and researchers. However, all too often, the research design clearly originates from a technologist’s perspective, showing relatively little knowledge of detailed learning science methods or findings. A good example of this mindset’s strengths and weaknesses is Google’s recent paper, “Towards Responsible Development of Generative AI for Education: An Evaluation-Driven Approach“. It reads like a paper largely concieved by technologists who work on improving generative AI and sharpened up by educational research specialists they consulted with after they already had the research project largely defined.

The paper proposes evaluation rubrics for five dimensions of generative AI tutors:

- Clarity and Accuracy of Responses: This dimension evaluates how well the AI tutor delivers clear, correct, and understandable responses. The focus is on ensuring that the information provided by the AI is accurate and easy for students to comprehend. High clarity and accuracy are critical for effective learning and avoiding the spread of misinformation.

- Contextual Relevance and Adaptivity: This dimension assesses the AI’s ability to provide responses that are contextually appropriate and adapt to the specific needs of each student. It includes the AI’s capability to tailor its guidance based on the student’s current understanding and the specific learning context. Adaptive learning helps in personalizing the educational experience, making it more relevant and engaging for each learner.

- Engagement and Motivation: This dimension measures how effectively the AI tutor can engage and motivate students. It looks at the AI’s ability to maintain students’ interest and encourage their participation in the learning process. Engaging and motivating students is essential for sustained learning and for fostering a positive educational environment.

- Error Handling and Feedback Quality: This dimension evaluates how well the AI handles errors and provides feedback. It examines the AI’s ability to recognize when a student makes a mistake and to offer constructive feedback that helps the student understand and learn from their errors. High-quality error handling and feedback are crucial for effective learning, as they guide students towards the correct understanding and improvement.

- Ethical Considerations and Bias Mitigation: This dimension focuses on the ethical implications of using AI in education and the measures taken to mitigate bias. It includes evaluating how the AI handles sensitive topics, ensures fairness, and respects student privacy. Addressing ethical considerations and mitigating bias are vital to ensure that the AI supports equitable learning opportunities for all students.

Of these, the paper provides clear rubrics for the first four and is a little less concrete on the fifth. Notice, though, that most of these are similar dimensions that generative AI companies use to evaluate their products generically. That’s not bad. On the contrary, establishing standardized, education-specific rubrics with high inter-rater reliability across these five dimensions is the first component of the programmatic, sector-wide approach to AI tutors that we need. Notice these are all qualitative assessments. That’s not bad but, for example, we do have quantitative data available on error handling in the form of feedback and hints (which I’ll delve into momentarily).

That said, the paper lacks many critical research components, particularly regarding the LearnLM-Tutor software the researchers were testing. Let’s start with the authors not providing outcomes data anywhere in the 50-page paper. Did LearnLM-Tutor improve student outcomes? Make them worse? Have no effect? Work better in some contexts than others? We don’t know.

We also don’t know how LearnLM-Tutor incorporates learning science. For example, on the question of cognitive load, the authors write,

We designed LearnLM Tutor to manage cognitive load by breaking down complex tasks into smaller, manageable components and providing scaffolded support through hints and feedback. The goal is to maintain an optimal balance between intrinsic, extraneous, and germane cognitive load.

Towards Responsible Development ofGenerative AI for Education: An Evaluation-Driven Approach

How, specifically, did they do this? What measures did they take? What relevant behaviors were they able to elicit from their LLM-based tutor? How are those behaviors grounded in specific research findings about cognitive load? How closely do they reproduce the principals that produced the research findings they’re drawing from? And did it work?

We don’t know.

The authors are also vague about Intelligent Tutoring Systems (ITS) research. They write,

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have shown that intelligent tutoring systems (ITS) can significantly improve student learning outcomes. For example, Kulik and Fletcher’s meta-analytic review demonstrates that ITS can lead to substantial improvements in learning compared to traditional instructional methods.

Towards Responsible Development ofGenerative AI for Education: An Evaluation-Driven Approach

That body of research was conducted over a relatively small number of ITS implementations because a relatively small number of these systems exist and have published research behind them. Further, the research often cites specific characteristics of these tutoring systems that lead to positive outcomes, with supporting data. Which of these characteristics does LearnLM Tutor support? Why do we have reason to believe that Google’s system will achieve the same results?

We don’t know.

I’m being a little unfair to the authors by critiquing the paper for what it isn’t about. Its qualitative, AI-aligned assessments are real contributions. They are necessary for a programmatic, sector-wide approach to AI tutor development. They simply are not sufficient.

ITS data sets for fine-tuning

ITS research is a good place to start if we’re looking to anchor our AI tutor improvement and testing program in solid research with data sets and experimental protocols that we can re-use and adapt. The first step is to explore how we can utilize the existing body of work to improve AI tutors today. The end goal is to develop standards for integrating the ongoing ITS research (and other data-backed research streams) into continuous improvement of AI tutors.

One key short-term opportunity is hints and feedback. If, for the moment, we stick with the notion of a “tutor” as software engaging in adaptive, turn-based coaching of students on solving homework problems, then hints and feedback are core to the tutor’s function. ITS research has produced high-quality, publicly available data sets with good findings on these elements. The sector should construct, test, and refine an LLM fine-tuning data set on hints and feedback. This work must include developing standards for data preprocessing, quality assurance, and ethical use. These are non-trivial but achievable goals.

The hints and feedback work could form a beachhead. It would help us identify gaps in existing research, challenges in using ITS data this way, and the effectiveness of fine-tuning. For example, I’d be interested in seeing whether the experimental designs used in hints and feedback ITS research papers could be replicated with an LLM that has been fine-tuned using the research data. In the process, we want to adopt and standardize protocols for preserving student privacy, protecting author rights, and other concerns that are generally taken into account in high-quality IRB-approved studies. These practices should be baked into the technology itself when possible and supported by evaluation rubrics when it is not.

While this foundational work is being undertaken, the ITS research community could review its other findings and data sets to see which additional research data sets could be harnessed to improve LLM tutors and develop a research agenda that strengthens the bridge being built between that research and LLM tutoring.

The larger limitations of this approach will likely spring the uneven and relatively sparse coverage of course subjects, designs, and student populations. We can learn a lot about developing a strategy for uses these sorts of data from ITS research. But to achieve the breadth and depth of data required, we’ll need to augment this body of work with another approach that can scale quickly.

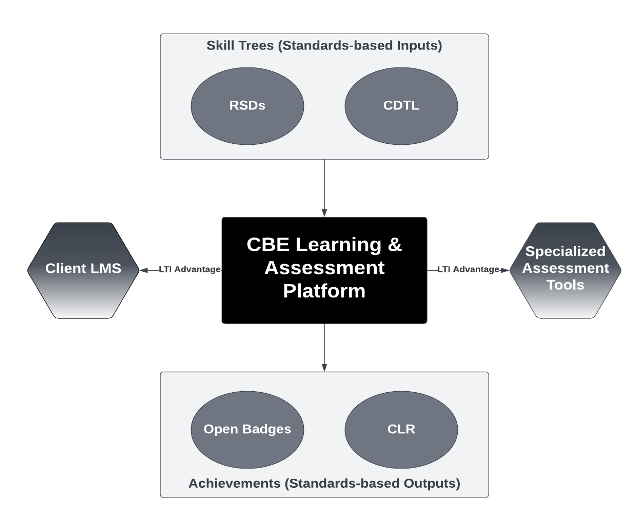

Expanding data sets through interoperability

Hints and feedback are great examples of a massive missed opportunity cost. Virtually all LMSs, courseware, and homework platforms support feedback. Many also support hints. Combined, these systems represent a massive opportunity to gather data about usage and effectiveness of hints and feedback across a wide range of subjects and contexts. We already know how the relevant data need to be represented for research purposes because we have examples from ITS implementations. Note that these data include both design elements—like the assessment question, the hints, the feedback, and annotations about the pedagogical intent—and student performance when they use the hints and feedback. So if, for example, we were looking at 1EdTech standards, we would need to expand both Common Cartridge and Caliper standards to incorporate these elements.

This approach offers several benefits. First, we would gain access to massive cross-platform data sets that could be used to fine-tune AI models. Second, these standards would enable scaled platforms like LMSs to support proven metheds for testing the quality of hints and feedback elements. Doing so would provide benefit to students using today’s platforms while enabling improvement of the training data sets for AI tutors. The data would be extremely messy, especially at first. But the interoperability would enable a virtuous cycle of continuous improvement.

The influence of interoperability standards on shaping EdTech is often underestimated and misunderstood. !EdTech was first created when publishers realized they needed a way to get their content into new teaching systems that were then called Instructional Management Systems (IMS). Common Cartridge was the first standard created by the organization now known as 1EdTech. Later, Common Cartridge export made migration from one LMS to another much more feasible, thus aiding in breaking the product category out of what was then a virtual monopoly. And I would guess that perhaps 30% or more of the start-ups at the annual ASU+GSV conference would not exist if they could not integrate with the LMS via the Learning Tool Interoperability (LTI) standard. Interoperability is a vector for accelerating change. Creating interoperabiltiy around hints and feedback—including both the importing of them into learning systems and passing student performance impact data—could accelerate the adoption of effective interactive tutoring responses, whether they are delivered by AI or more traditional means.

Again, hints and feedback are the beachhead, not the end game. Ultimately, we want to capture high-quality training data across a broad range of contexts on the full spectrum of pedagogical approaches.

Capturing learning design

If we widen the view beyond the narrow goal of good turn-taking tutorial responses, we really want our AI to understand the full scope of pedagogical intent and which pedagogical moves have the desired effect (to the degree the latter is measurable). Another simple example of a construct we often want to capture in relation to the full design is the learning objective. ChatGPT has a reasonably good native understanding of learning objectives, how to craft them, and how they relate to gross elements of a learning design like assessments. It could improve significantly if it were trained on annotated data. Further, developing annotations for a broad spectrum of course design elements could improve its tutoring output substantially. For example, well-designed incorrect answers to questions (or “distractors”) often test for misconceptions regarding a learning objective. If distractors in a training set were specifically tagged as such, the AI could better learn to identify and probe for misconceptions. This is a subtle and difficult skill even for human experts but it is also a critical capability for a tutor (whether human or otherwise).

This is one of several reasons why I believe focusing effort on developing AI learning design assistants supporting current-generation learning platforms is advantageous. We can capture a rich array of learning design moves at design time. Some of these we already know how to capture through decades of ITS design. Others are almost completely dark. We have very little data on design intent and even less on the impact of specific design elements on achieving the intended learning goals. I’m in the very early stages of exploring this problem now. Despite having decades of experience in the field, I am astonished at the variability in learning design approaches, much of which is motivated and little of which is tested (or even known within individual institutions).

On the other side, at-scale platforms like LMSs have implemented many features in common that are not captured in today’s interoperability standards. For example, every LMS I know of implements learning objectives and has some means of linking them to activities. Implementation details may vary. But we are nowhere close to capturing even the least-common-denominator functionality. Importantly, many of these functions are not widely used because of the labor involved. While LMSs can link learning objectives to learning activities, many course builders don’t do it. If an AI could help capture these learning design relationships, and if it could export content to a learning platform in a standard format that preserves those elements, we would have the foundations for more useful learning analytics, including learning design efficacy analytics. Those analytics, in turn, could drive improvement of the course designs, creating a virtuous cycle. These data could then be exported for model training (with proper privacy controls and author permissions, of course). Meanwhile, less common features such as flagging a distractor as testing for a misconception could be included as optional elements, creating positive pressure to improve both the quality of the learning experiences delivered in current-generation systems and the quality of the data sets for training AI.

Working at design time also puts a human in the loop. Let’s say our workflow follows these steps:

- The AI is prompted to conduct turn-taking design interviews of human experts, following a protocol intended to capture all the important design elements.

- The AI generates a draft of the learning design. Behind the scenes, the design elements are both shaped by and associated with the metadata schemas from the interoperability standards.

- The human experts edit the design. These edits are captured, along with annotations regarding the reasons for the edits. (Think Word or Google Docs with comments.) This becomes one data set that can be used to further fine-tune the model, either generally or for specific populations and contexts.

- The designs are exported using the interoperability standards into production learning platforms. The complementary learning efficacy analytics standards provide telemetry on the student behavior and performance within a given design. This becomes another data set that could potentially be used for improving the model.

- The human learning designers improve the course designs based on the standards-enabled telemetry. They test the revised course designs for efficacy. This becomes yet another potential data set. Given this final set in the chain, we can look at designer input into the model, the model’s output, the changes human designers made, and improved iterations of the original design—all either aggregated across populations and contexts or focused on a specific population and context.

This can be accomplished using the learning platforms that exist today, at scale. Humans would always supervise and revise the content before it reaches the students, and humans would decide which data they would share under what conditions for the purposes of model tuning. The use of the data and the pace of movement toward student-facing AI become policy-driven decisions rather than technology-driven. At each of the steps above, humans make decisions. The process allows for control and visibility regarding the plethora of ethical challenges that face integrating AI into education. Among other things, this workflow creates a policy laboratory.

This approach doesn’t rule out simultaneously testing and using student-facing AI immediately. Again, that becomes a question of policy.

Conclusion

My intention here has been to outline a suite of “shovel-ready” initiatives that could be implemented realitvely quickly at scale. It is not comprehensive; nor does it attempt to even touch the rich range of critical research projects that are more investigational. On the contrary, the approach I outline here should open up a lot of new territory for both research and implementation while ensuring the concrete already being poured results in a safe, reliable, science- and policy-driven foundation.

We can’t just sit by and let AI happen to us and our students. Nor can we let technologists and corporations become the primary drivers of the direction we take. While I’ve seen many policy white papers and AI ethics rubrics being produced, our approach to understanding the potential and mitigating the risks of EdTech AI in general and EdTech tutors in particular is moving at a snail’s pace relative to product development and implementation. We have to implement a broad, coordinated response.

Now.