To understand the chaos that is the world today it helps to look back a decade.

This past year, world representatives met at COP29 to fight climate change in a place led by an authoritarian regime dependent on fossil fuels. The Israeli government under Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has been massacring Palestinians in Gaza. The United States bombed Iran in an attempt to eliminate its nuclear capability. And U.S. President Donald Trump and an increasing number of European leaders have closed their doors to immigrants and refugees.

In great contrast, when News Decoder launched 10 years ago, 196 nations signed onto the landmark agreement known as the Paris Accords, ushering in the hope that together we could cool down the planet. The administration of then-U.S. President Barack Obama signed a historic agreement with Iran, in which Iran would get rid of 97% of its supply of enriched uranium. A million refugees flooded into Europe from conflicts in Syria and elsewhere.

In the years in between, the world locked down during the Covid-19 pandemic, Great Britain exited the European Union, the #MeToo movement erupted across the world, nations across the globe began legalizing same sex marriage, Russia invaded Ukraine, Trump got elected, tossed out and re-elected and we began ceding everything to artificial intelligence.

Can you imagine coming of age in that world?

Decoding world events

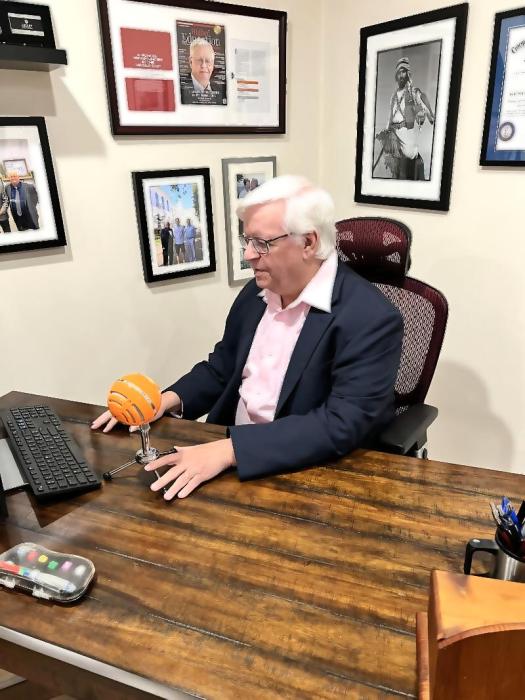

When Nelson Graves founded News Decoder to help young people “decode” the world through news, it seemed that we lived in an age of optimism. Now young people feel helpless and disconnected. In April 2024, the World Economic Forum reported that young people worldwide are increasingly unhappy and this trend would have real consequences for the future.

“We live in a world where teenagers grapple with a sense of crisis before adulthood; a time when young people, historically beacons of optimism, report lower happiness than their elders,” the report said.

But even back in 2015, Nelson knew things would change. He’d spent years as a foreign correspondent covering world events.

“Anyone with a sense of history and someone with experience in following current events — especially a foreign correspondent — would have known that the world is most likely to change when you’re least expecting it,” he said. “Nothing is immutable — except the truism that the political pendulum is always swinging.”

The roots of Brexit, the Make America Great Again movement in the United States and antipathy towards immigrants were already deep in 2015, even if they were largely underground and out of sight, he said.

A decade later, News Decoder’s mission of connecting young people to the world around them seems more relevant than ever.

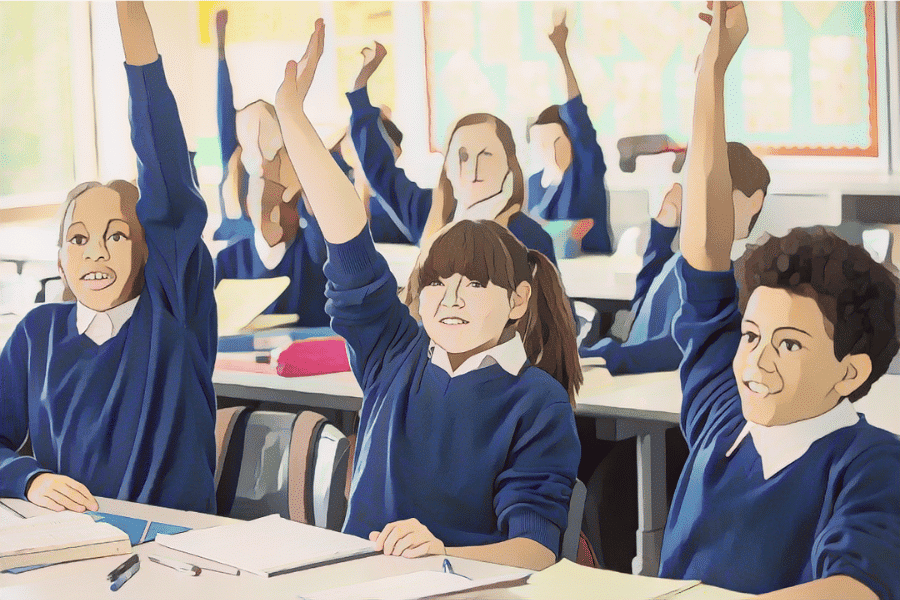

For 10 years, the high school students News Decoder has worked with have explored — through articles, podcasts, videos and photo essays and in live, cross-border dialogues — how problems in their communities connect to things happening elsewhere in the world. In 2016, for instance, a student studying abroad in China worked with News Decoder to explore how growing consumerism was leading to mountains of trash and created an army of people who mined that trash building up around them.

That same year in an online roundtable, News Decoder brought together students from the Greens Farms Academy in the United States with students from Kings Academy in Jordan, Aristotle University in Greece and School Year Abroad in France to discuss the ongoing war in Syria and the worldwide crisis of Syrian refugees.

Kindling curiosity

One of the Greens Farms Academy students who participated, Samyukt Kumar, further explored the topic in an article News Decoder published that year. Looking back, he now tells, the practical experience it gave him was valuable.

“Less for the substance but more for the practical experience,” he said. “My views on these topics evolved significantly as I received greater education and real-world exposure. But I still reap the benefits from gaining more confidence in my writing, learning to embrace the editing process and engaging my curiosity about the world.”

In 2017, a News Decoder student at Haverford College in the United States explored the problem of migrants flooding into her home country of Italy. She came to this conclusion:

“The roots of the problem lie outside of Italy, which nonetheless bears a heavy burden as the first EU destination for thousands of Africans crossing the Mediterranean,” she wrote. “A solution to the migration crisis depends not only on Italy’s good will — now being stretched to the limits — but also on the willingness of the rest of Europe and the international community to tackle the armed conflicts, poverty and human rights abuses that stir so many Africans to attempt the perilous Mediterranean crossing.”

Fast forward to 2025. News Decoder worked with high school students in the British Section at the Lycée International Saint-Germain-en-Laye outside of Paris to take what they learned about the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and find and tell narrative stories through podcasts. They explored such things as the problem of poverty in resource-rich areas of Africa and the connection between actions of multinational corporations and climate change.

Crossing borders

In Switzerland, News Decoder worked with students at Realgymnasium Rämibühl Zürich on a series of articles that explored gender inequity in sports, the connection between social media and the decline of democracy, how a local community is affected when it hosts a world conference and the connection between the quality of life in a country and the people’s willingness to pay for that through high prices and high taxes.

And in monthly “Decoder Dialogues” News Decoder put together students from countries such as the United States, Colombia, France, India, Belgium and Rwanda in online roundtables to discuss such topics as the future of journalism, climate action, censorship, leadership and artificial intelligence.

Through the exploration of a problem in the world, by seeking out experts who can put it into context and by seeking out different perspectives from other places, students make sense out of chaos. They begin to see that there are people out there thinking about these problems in different ways and seeking solutions to them.

Ultimately, the message News Decoder wants students to take away is that you don’t need to run from complicated problems. You don’t need to disengage from the news and the events happening around you. By delving more into a topic or issue or controversy, you can begin to understand it and see the path forward.

At News Decoder, we believe people should be able to listen to each other and exchange viewpoints to work through problems across differences and borders. Back in 2015, Graves posed this challenge: How to tap into the intellectual energy of the generation that will soon assume leadership in business, government, academia and social enterprise?

For the past 10 years we have worked to empower young people by giving them the information they need, connecting them to the world around them and providing them a forum for expression. For a decade we have helped them find coherence out of the chaos around them — and we intend to continue doing that for the next 10 years.

One thing we know: 10 years from now the world will be a lot different from what it is now.

“While no one has a perfect crystal ball, you can be sure that nothing remains unchanged for long,” Graves said. “Yesterday’s mortal enemy can become a fast friend — think of U.S. relations with Vietnam since the 1950s. Lesson: Always expect change, even if you can’t anticipate the precise contours, and don’t project linearly into the future. As ever, keep an open mind and beware confirmation bias.”

That’s the message News Decoder tries to instill in the young people we work with. After all, a decade from now, they will be the ones making that change happen.