It has been just six years since the Paris Climate Agreement set a race against time to rein in global heating. But the Earth is sending ever-harsher signals of alarm.

When the accord was signed, we were on course for global heating of 4°C from the start of the industrial era to the end of this century. Now the figure is around 2.7°C. So something has been achieved, but relative safety comes at no more than 1.5°C.

There is still a gap between the policies put in place over the past six years and what is needed to achieve that lower figure, the International Energy Agency (IEA) said in its annual outlook, published in October.

Yet we know what to do: substitute renewable energy for the power we get from fossil fuels by mid-century; decarbonize industry and adapt land-use to trap carbon in soil and plants; adapt our means of transport and our growing cities to use less energy; and protect marine areas to enhance carbon absorption in oceans.

“Two parallel and contradictory processes are in play,” wrote environmentalist and author George Monbiot in a Guardian opinion piece on November 3. “At climate summits, governments produce feeble voluntary commitments to limit the production of greenhouse gases. At the same time, almost every state with significant fossil reserves … intends to extract as much as they can.”

Everything depends, he concluded, on which process prevails.

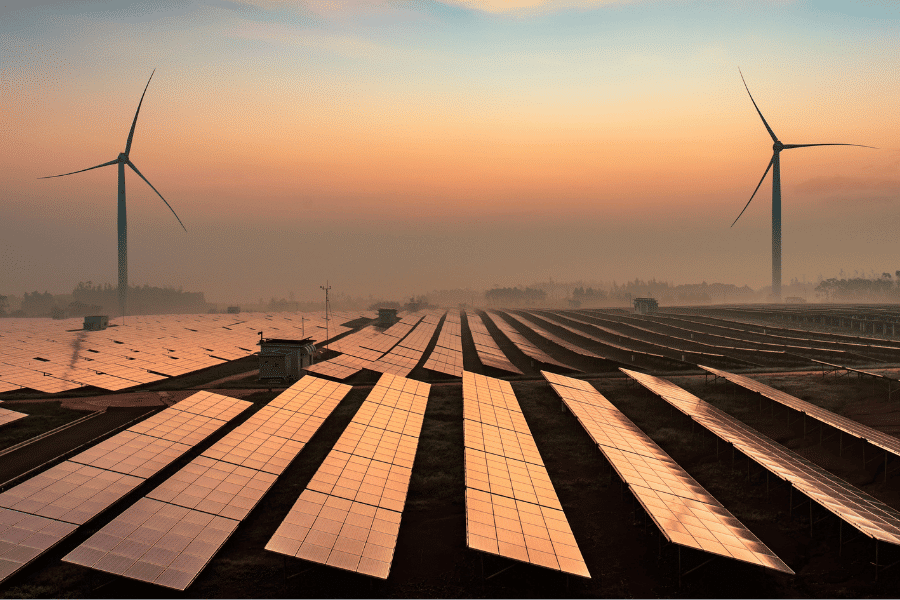

Making strides in renewable energy

Similar tensions are in play at industrial and economic levels. On the plus side, there is now a surprisingly strong backstory in renewable wind and solar energy, particularly solar, and particularly in the United States, the heaviest polluter historically per person, and China, the biggest polluter in absolute quantities of its emissions.

The energy crisis resulting from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine last February has prompted policies that will boost clean energy, the IEA added in its World Energy Outlook, which projects trends out to 2030.

While the crisis has created a temporary upside for coal, in the long run, production of renewable energy will outpace the production of energy derived from fossil fuels, the report said.

Another positive sign is the nascent hydrogen industry.

Widely occurring and carbon-free, this gas could decarbonize long-distance travel and industries that are heavy emitters. Producing it without carbon emissions implies using intermittent renewable energy when it is over-abundant, a virtuous circle.

However, none of this is yet at industrial scale — barring a few hydrogen-powered trains. Not all claims for hydrogen can be borne out, and it is not yet a viable financial concern.

There is a significant plus on the political front with the election of Luiz Ignácio Lula da Silva as Brazil’s next president. He promises to end the record deforestation of the Amazon under his predecessor, Jair Bolsonaro, and is to take office in January.

But there is no slowdown in fossil fuels.

Yet investment in fossil fuels still dwarfs cash flowing into renewables, even though they offer economic advantages. The United States, for example, has ploughed over $9 trillion into oil and gas projects in Africa since it signed the Paris Agreement, The Guardian found.

Africa, a continent starved of cash for energy but with vast potential for solar power, is now under pressure — including from international oil companies operating in its national parks — to exploit its fossil fuel resources just to bring electric power to its people.

The fossil fuel industry’s damage doesn’t end there. There has been drastic under-counting of carbon emissions, a new tracking tool backed by former U.S. Vice President Al Gore has found. Oil and gas companies have underestimated their emissions threefold, Gore said when launching the tool at the United Nations Climate Summit (COP 27) in Egypt this month.

“For the oil and gas sector it is consistent with their public relations strategy and their lobbying strategy. All of their efforts are designed to buy themselves more time before they stop destroying the future of humanity,” The Guardian quoted Gore as saying.

Investing in Africa

Across the world, policies are in place to invest over $2 trillion in clean energy by 2030, half as much again as today, led by the United States and China, but also including the European Union, India, Indonesia and South Korea, according to the IEA.

In the United States, solar was already becoming the star of the new energy scene, according to an annual report from Berkeley National Labs. The country added 1.25 terrawatts of solar capacity in 2021. That’s more than the installed solar capacity in the entire world, which reached 1 terrawatt in early 2022.

That was before the Biden Administration enacted the Inflation Reduction Act, which brings extra impetus for the sector. The United States plans to add 2-1/2 times its existing solar and wind capacity every year between now and 2030 and grow its fleet of electric vehicles seven-fold, the IEA said.

At the same time, Africa is desperate for energy investment.

To provide access to electricity for its population, the continent would need $25 billion per year, the IEA said in its annual Africa Energy Outlook, published in June. “This is around 1% of global energy investment today, and similar to the cost of building just one large liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminal,” it said.

The continent has 60% of the world’s best solar resources but only 1% of installed solar photovoltaic capacity. This is already the cheapest source of power in many parts of Africa and would outcompete all other energy sources across the continent by 2030, the IEA said.

The energy watchdog projects that solar, wind, hydropower and geothermal energy would provide over 80% of new power generation capacity in Africa by 2030. No new coal-fired power plants would be built once those now under construction are completed. Half the cost of adding new solar installations out to 2025 could be covered by investments that would otherwise have gone into discontinued coal plants.

Yet this assessment leaves out the plans for increased oil and natural gas developments on the continent.

Pressure from energy companies

A report just published by Rainforest UK and Earth Insight 2022 found that the area of land allocated across Africa for such developments is set to quadruple under existing plans. That report focuses on the Congo Basin, but in East Africa, French oil major TotalEnergies is pushing ahead with a large-scale oil project and trans-continental pipeline in Uganda.

A first cargo of liquefied natural gas has just left Mozambique after multiple delays caused by an insurgency in the region of the gas field, in a venture involving several oil companies.

These oil and gas projects would lock the continent into fossil fuels for decades to come and blow a hole in the bid to keep global heating to no more than 1.5°C.

These energy projects have wide support among African leaders, who contrast the immediacy of such investments and their benefits for their countries with the reluctance of Western nations to put up the finance agreed over a decade ago for energy transitions and preservation of biodiversity.

African environmentalists question the wisdom of this carbon bomb. But it is hard to dismiss the idea that broken promises by the countries that have caused the climate crisis has driven Africa into the arms of the fossil fuel industry.

TotalEnergies’ CEO Patrick Pouyanné argues that the world cannot quit fossil fuels before it has alternative sources of energy.

“The mistake being made now is to think that the solution for the climate is to abandon fossil fuels,” he said in an interview with French TV station LCI on November 17. “The solution is first to build the new decarbonized energies that we need.”

“If you do both at the same time, what happens?,” Pouyanné said. “Exactly what you reproach us for — prices rise because of the rarity of supply, because the demand for oil is not falling.”

The monopoly power of fossil fuel firms

These energy companies have long fought the switch from fossil fuels to renewables.

Half a century ago, Total concealed a report it had commissioned that clearly explained how burning fossil fuels would cause global heating and the consequences we are seeing today.

Other oil and gas companies, notably Exxon, acted similarly and responded to their findings by funding climate-denying think tanks and political lobbyists.

More recently, as the evidence mounted, they turned their attention to lobbying for exemptions, even though the scientific consensus demands that to achieve the 1.5°C limit on warming, there can be no new oil, gas or coal exploration or extraction.

A record number of fossil fuel lobbyists attended this month’s climate summit in Egypt (see the graphic here).

Fossil fuels no longer make economic sense.

The sector is a good example of reality flouting economic theory, which teaches that if a new technology reaches a point where it outcompetes an existing one, the new technology will replace the older one.

This should be happening with solar versus coal, oil and gas — and indeed is predicted to happen by 2050. Meanwhile, harmful emissions continue to rise.

Energy markets and the fossil fuel firms themselves do not obey basic economics for the simple reason that they are monopolies with the power to skew conditions in their favor.

The oil producers’ monopoly, in the form of OPEC, has controlled production to keep prices higher for decades. In the 1990s, the big Western oil companies went through a frenzy of mega-mergers that created today’s top five — Shell, ExxonMobil, BP, Chevron, and ConocoPhillips — whose sheer size gives them disproportionate bargaining and lobbying power.

Now activists are trying to gain support for a Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty as a way of reining in the root cause of the climate emergency. The initiative was put before the United Nations in September and the COP 27 climate summit in November.

“Will you be on the right side of history? Will you end this moral and economic madness?” Ugandan climate activist Vanessa Nakate asked global leaders at the summit.

On that, the jury is still out.

Landmark deal opens way for loss and damage fund

It has taken 27 climate summits, but the COP 27 in Egypt finally managed to pull out an agreement to set up a specific fund to aid poor countries hit by damage caused by climate disasters. The deal was approved on November 20 after a marathon negotiating session.

The proposal had been fought tooth and nail by the rich industrialized countries whose emissions have fostered global heating, stirring resentment among poorer countries who have suffered the most extreme consequences and have the least ability to mitigate the damage.

Details will be hammered out over the coming year, and there is as yet no money in the fund. It was nevertheless a major step forward.

However, the final agreement failed to call for phasing out all fossil fuels and for warming emissions to peak by 2025, both heavily opposed by oil-producing countries, raising fears that the goal of limiting warming to 1.5°C by mid-century will not be achievable.

Questions to consider:

1. Where is a major boom in solar energy taking place?

2. What is Africa’s energy dilemma?

3. Why do you think fossil fuel majors have so much influence?