Under NATO, 32 countries have pledged to defend each other. Is the United States the glue that holds it all together?

Source link

Category: Europe

-

Decoder Replay: Isn’t all for one and one for all a good thing?

-

Climate change brings new worries to an old industry

It is another early harvest for the Vignoble des Agaises, a vineyard in the region of Mons in Belgium. While the country is widely known for its variety of Trappist beers, the proximity that Mons and the region of Wallonia bears to French Burgundy and Picardie influences the local drinking culture.

Indeed, wine means a great deal to Arnaud Leroy, the vineyard’s sales manager. He and his family have, for 20 years now, pioneered the potential of the frontier that is Southern Belgium in the production of champagne and other sparkling wines.

Wine has been a staple of the regional economy and culture for centuries and has been a vital part of Leroy’s life and that of millions of other people around the world. Recently, however, a series of early frosts have decimated large quantities of the harvests in the lands stretching from Lombardy to Flanders.

These poor harvests have left many local vineyards in a state of financial uncertainty. Such events aren’t unique to the regions of Western Europe. Similar problems and hardships have been experienced in most other winemaking regions of Europe and have caused harm to winemaking communities around the world.

Europe has been hit by what may only be compared to a “tidal wave” of change as previously predictable and constant meteorological conditions that have allowed winemaking to prosper in these regions for millennia have been altered significantly in the span of nearly a few decades.

“In the last 10 years we have always harvested in October,” Leroy said. “But recent harvests have systematically been earlier and earlier into September, this year’s harvest being around the third of September.” This seemingly light change may have an outsized impact on the nature of the wine produced, deeply affecting the wine’s taste and composition.

With wine, climate is everything.

Wine is widely regarded as one of the most climate-sensitive crop cultures, experiencing possible changes to its texture, taste and tannin density from even the smallest constant meteorological change.

Earlier harvests can affect the wine’s taste, as a low maturation of the grapes may cause an increased sourness and a less sweet taste as well as a lighter, less-defined aroma, while spring frosts like the ones experienced in the last few years may cause the exact opposite, making a much sweeter, less-acidic and more tannin heavy wine.

Thus, the taste of many well-established sorts and brands of wines may be inconsistent and altered significantly by the seasonal changes brought by the climate crisis. Renowned regions such as Tuscany, Burgundy, Greece, the Rhine Valley, California and many more may be considerably different — and potentially even in danger of being displaced in a few decades.

Indeed, it would seem one of Europe’s oldest industries is in a crisis. Wine has been a luxury product for thousands of years and holds a cultural, economic, social and historical value that few other comparable goods hold.

Associated with the higher class and nobility for centuries and being a valued good for over 10 millennia, wine is arguably one of Europe’s most important goods. It holds a vital place in Christian tradition and practice and — having two saints and a multitude of deities of hundreds of religions and mythologies — it is perhaps one of the most important components to the cultural development of the continent and perhaps, of the world.

Addressing climate change

The changes experienced in the last decades have not gone unnoticed. Many oenologists and vintners have called for more attention and action in the fight against climate change and the seasonal changes it may bring. What is now often called a crisis is even further fueled by other external causes.

“The younger generation simply consumes less alcohol,” Leroy said. This makes the financial impact of said seasonal effects even more devastating to the smaller domaines and vineyards while bigger producers cling on to what is left of their harvests.

This year’s harvest has been plentiful and record-breaking in some regions such as Champagne, mostly due to favourable conditions and the development of better technology. But this success has taken media attention away from the longer term crisis.

In the summer of 2025 large floods hit the regions of Picardie in Belgium and Champagne in France, causing two deaths and large amounts of damage to private property and agricultural lands, further hindering the European wine market.

Even worse, in the case of an increase of two degrees Celsius (35 degrees Fahrenheit) of global temperatures, scientists warn that the world may pass a tipping point (a point of irreversibility) in the patterns of ocean currents, potentially causing drastic change to the European climate as we know it — a threat that has been mostly ignored by mass media and climatological institutions.

And that threat is only about 20 years from now.

Some grapes suffer, others thrive.

This doesn’t mean, however, that absolutely all regions will suffer and that there are no solutions. In some southern parts of Sweden for instance, a multitude of new, more resilient vines have laid the foundation for a Scandinavian wine industry, made possible due to the changes experienced in the local climate.

“While there have been some exceptions, notably in 2024, wine production has been top quality,” Leroy said. “The earlier harvests have their advantages.”

As older, more renowned wine producing regions lose their significance, this instability may prove a good time for newer regions and producers with other defined traits such as Scandinavia, the Balkans and the Agaises vineyard with their chalky ground and distinct latitude to fill in the gap left by the older producers.

Of course, a solution to the entire issue would be the halting or at least the delaying of climate change through the lowering of consumption and of carbon emissions. But such halting would take a tremendous individual and national effort that is lacking in Europe and in the world.

Thus, this problem presents us with yet another reason to continue the costly yet imperative fight against the climate crisis and all effects that it causes.

Questions to consider:

1. What does the author mean by a “tidal wave” of change that has hit Europe?

2. How can climate change help grape growing in some regions when it devastates other regions?

3. Can you think of other long-time industries that have been affected by climate change?

-

conflict, peace and international education

It’s that time of year again. On streets and in shops across the UK this, someone will have been be selling poppies. And today, on Remembrance Sunday, at War Memorials from tiny villages to Whitehall, people will gather for a period of silence. A moment to reflect, to remember.

For me personally, there is a family connection. My paternal great-grandfather was killed in WWI, leaving four young children. His name is on the vast Tyne Cot memorial in Belgium, one of 35,000 of the missing who died in the Ypres Salient after August 16, 1917, and have no known grave.

But I also think of another memorial, the one I gathered around for the years I worked at Sheffield University. This is the moving tribute to the students and staff who lost their lives in two World Wars.

This carved stone monument at the University’s core was once located in the original library, and it contains arguably the most sacred and painful book in its collection – a Book of Remembrance.

Sheffield University had its own battalion in WWI and it was almost completely destroyed on the first day of the Battle of the Somme in 1916. Some 512 young men lost their lives in a single day. I was once given permission to lift off the glass cover and open the book. It was shocking, each page crammed full of so many hundreds of names.

For many of those students, hopefully joining up and travelling to France was the first time they had been overseas, just as it was for my great-grandfather. He left his mining village on the unluckiest of journeys – first to Gallipoli where he was gassed, and then to France where he died in the mud.

Today, students have a very different opportunity for travel, for connection. A century after my great-grandfather died, I have travelled the world in peacetime thanks to international education. I’ve been to Delhi and seen the vast war memorial at India Gate with its eternal flame and walls of other names – Hindu, Sikh, Muslim. I have friends from China whose relatives long ago would have dug the trenches as part of as part of the 140,000 strong Chinese Labour Corps for the British and French armies.

Remembrance Day isn’t a British only tradition – a whole world was drawn into those terrible events.

What international students teach us now

And I have international students friends who don’t need a poppy to remind them to remember because they come from countries with current experience of conflict.

Who are they? A refugee scholar from Syria working on environmental sustainability. A Gaza scholar who rejects the language of resilience and uses her research to build deep understanding. A friend in Singapore who has family in Russia and Ukraine. And the Afghan scholars who have become not only friends but family, those who teach us all that the peace to sit with your loved ones and share a meal is never to be taken for granted. That for young girls and women to access education, university, careers and have choices is a right hard won that must be cherished. Each of them is also my teacher.

As the world changes, nationalism grows and spheres of influence are fortified by economic and literal weapons, those who understand one another are more important than ever

And this is also why I believe in international education. Peace takes understanding. It takes work. As the world changes, nationalism grows and spheres of influence are fortified by economic and literal weapons, those who understand one another are more important than ever.

It is a tragedy that language courses close because, as John le Carré said, learning a language is an act of friendship. But international education in all its forms is also what my NISAU friends call a ‘living bridge’.

Whether it happens through traditional programmes of overseas study, short courses, institutional partnerships, TNE or internationalisation at home, global education offers a precious opportunity to meet in peace. To gain a perspective not only on what others think and how they see the world, but about yourself.

Why it matters that #WeAreInternational

When years ago we founded a campaign called #WeAreInternational , it was a statement not about a structure of higher education but about who we are and want to be. It doesn’t mean abandoning your identity, it means opening it up to possibility. That is in itself an education.

John Donne famously wrote that no man is an island but that we are deeply connected to one another, all of us connected to the continent. And when others are harmed, we are all diminished. That the bell that tolls for any life is ringing for humanity too.

On Remembrance Sunday this year, as we are urged never to forget, there is also an implicit call to action – not to wage war but to build peace. How do we do that? Nobody is pretending it’s easy, but I think the education we are privileged to support has a very human part to play.

I think of the words of my Afghan scholar friend Naimat speaking at City St George’s University of London to students earlier this week. As the minute’s silence begins on today, I will think of my great-grandfather Robert, the lost students of Sheffield University, and the words of this international student who knows of what he speaks.

To achieve peace at all times, we must do three things:

- Acknowledge the past: we must study and accept the hard lessons, the disconnected dots, and the mistakes of history.

- Act in the present: we must stand up against injustice wherever it occurs, recognising that a violation of human rights in one corner of the world eventually casts a shadow over all of us.

- Prioritise the future: we must commit to sustained dialogue – not just talk, but a genuine exchange of ideas where all voices, especially the most marginalised, are heard and valued.

Dialogue, he says, is the non-violent tool we possess to sustain peace. It is how we convert fear into understanding, and resentment into cooperation. And international education offers a precious and powerful opportunity for both.

-

International Student Mobility Data Sources: A Primer

Part 1: Understanding the Types of Sources and Their Differences

There has perhaps never been more of a need for data on globally mobile students than now. In 2024, there were about 6.9 million international students studying outside their home countries, a record high, and the number is projected to grow to more than 10 million by 2030. Nations all around the world count on global student mobility for a number of reasons: Sending nations benefit by sending some of their young people abroad for education, particularly when there is less capacity at home to absorb all demand. Many of those young people return to the benefit of the local job market with new skills and knowledge and with global experience, while others remain abroad and are able to contribute in other ways, including sending remittances. Host nations benefit in numerous ways, from the economic contributions of international students (in everything from tuition payments to spending in the local economy) to social and political benefits, including building soft power.

At the same time, economic, political, and social trends worldwide challenge the current ecosystem of global educational mobility. Many top destinations of international students, including Canada and the United States, have developed heavily restrictive policies toward such students and toward migrants overall. The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated that one global challenge can upend international education, even if temporarily.

Data plays a key role in helping those who work in or touch upon international education. All players in the space—from institutional officials and service providers to policymakers and researchers—can use global and national data sources to see trends in student flows, as well as potential changes and disruptions.

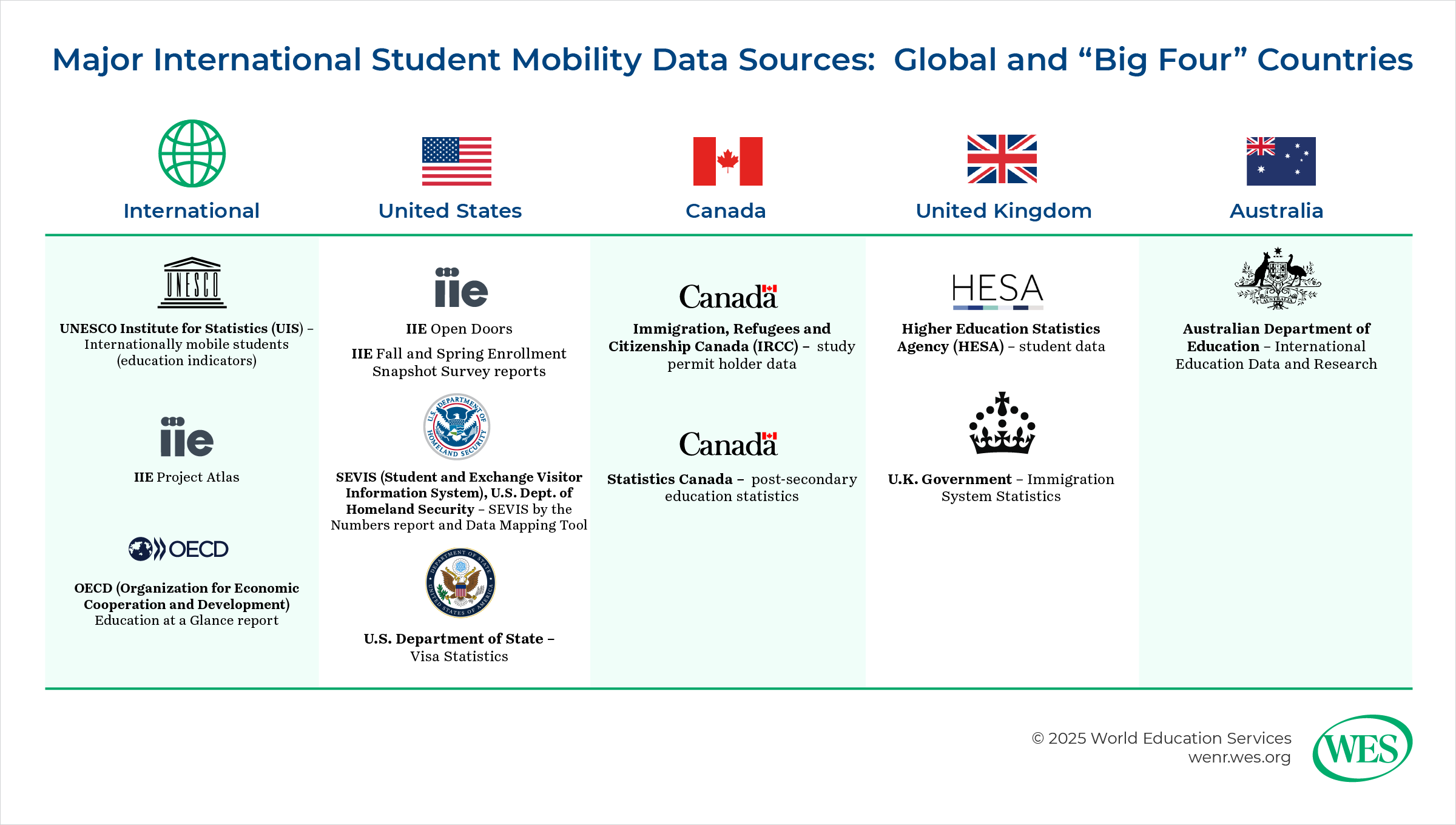

This article is the first in a two-part series exploring global student mobility data. In this first article, I will delve into considerations that apply in examining any international student data source. In the second, forthcoming article, we will examine some of the major data sources in global student mobility, both global and national, with the latter focused on the “Big Four” host countries: the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia.

In utilizing any global student mobility data source, it is crucial to understand some basics about each source. Here are some key questions to ask about any source and how to understand what each provides.

Who collects the data?

There are three main types of entities that collect student mobility data at a national level:

- Government ministries or agencies: These entities are generally mandated by law or statute to collect international student data for specific purposes. Depending on the entity’s purview, such data could include student visa or permit applications and issuances, students arriving at ports of entry (such as an airport or border crossing), enrollment in an educational institution, or students registered as working during or after completing coursework.

- Non-governmental organizations (NGOs): Non-profit entities focused on international education or related fields such as higher education or immigration may collect international student data, sometimes with funding or support from relevant government ministries. One good example is the Institute of International Education (IIE) in the U.S., which has collected data on international students and scholars since 1948, much of that time with funding and support from the U.S. Department of State.

- Individual institutions: Of course, individual universities and colleges usually collect data on all their students, usually with specific information on international students, sometimes by government mandate. In countries such as the U.S. and Canada, these institutions must report such data to governmental ministries. They may also choose to report to non-governmental agencies, such as IIE. Such data may or may not otherwise be publicly available.

At the international level, the main data sources are generally an aggregation of data from national sources. There are three main efforts:

How are the data collected?

The method in which mobility data are collected affects the level of accuracy of such data. The sources that collect data internationally or on multiple countries, such as UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) and IIE’s Project Atlas, are primarily aggregators. They collect the data from national sources, either government ministries or international education organizations, such as the British Council or the Canadian Bureau for International Education (CBIE).

For primary data collection, there are three main methods:

- Mandatory reporting: Certain government entities collect data by law or regulation. Data are naturally collected as part of processing and granting student visas or permits, as the S. State Department and Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) do. In other cases, postsecondary institutions are required to track and report on their international students—from application to graduation and sometimes on to post-graduation work programs. This is the case in the U.S. through SEVIS (the Student and Exchange Visitor Information System), overseen by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), through which deputized institutional officials track all international students. The data from this system are reported regularly by DHS. In other cases, data are collected annually, often through a survey form, as Statistics Canada does through its Postsecondary Student Information System (PSIS).

- Census: Some non-profit organizations attempt to have all postsecondary institutions report their data, often through an online questionnaire. This is the method by which IIE obtains data for its annual Open Doors Report, which tracks both international students in the U.S. and students enrolled in U.S. institutions studying abroad short-term in other countries.

- Survey: A survey gathers data from a sample, preferably representative, of the overall population—in this case, higher education institutions—to form inferences about the international student population. (This should not be confused with the “surveys” issued by government agencies, usually referring to a questionnaire form, typically online nowadays, through which institutions are required to report data.) This method is used in IIE’s snapshot surveys in the fall and spring of each year, intended to provide an up-to-date picture of international student enrollment as a complement to Open Doors, which reflects information on international students from the previous academic year.

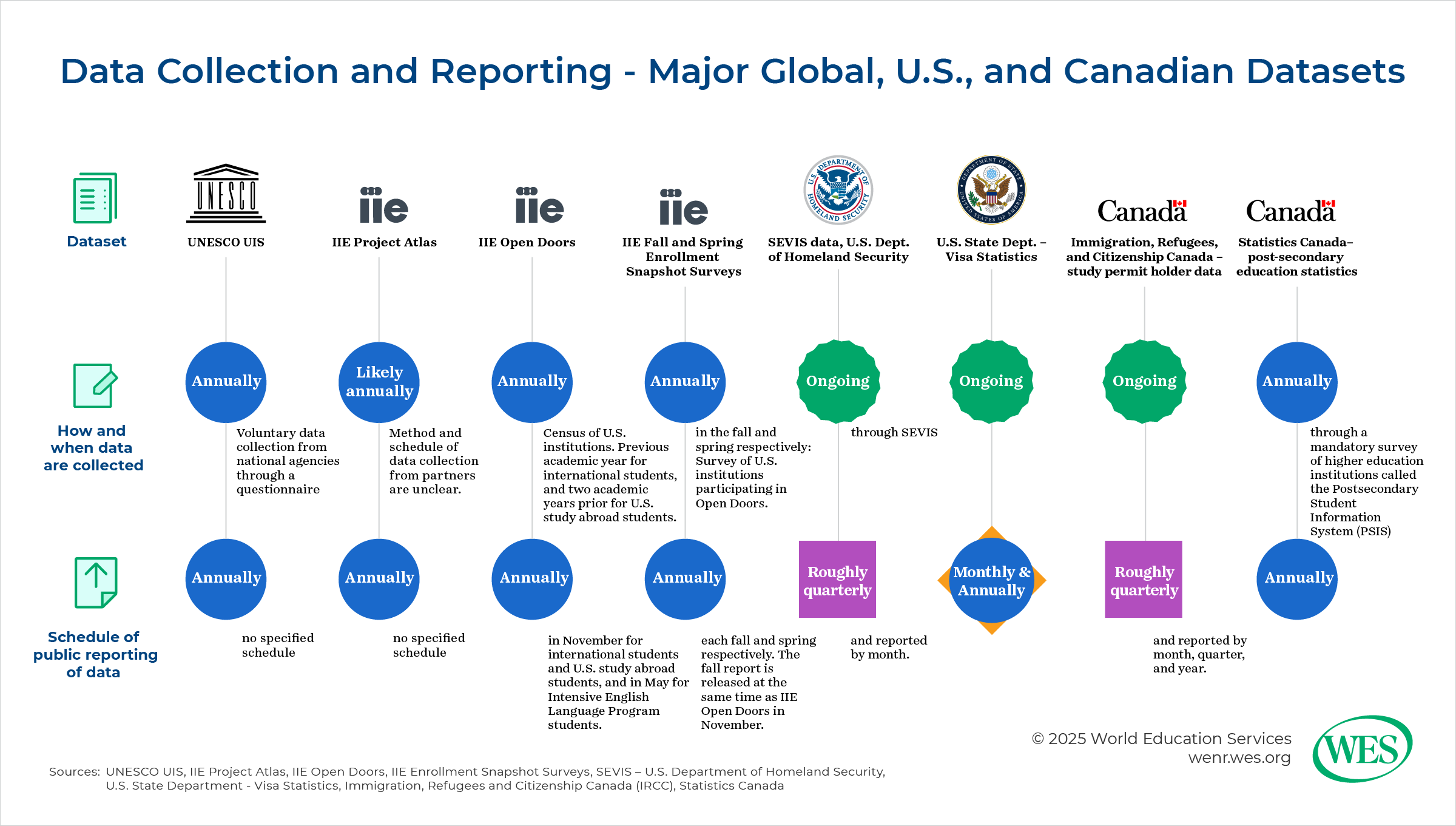

When are the data collected and reported?

In considering data sources, it is important to know when the data were collected and what time periods they reflect. Government data sources are typically the most up-to-date due to their mandatory nature. Data are often collected continuously in real time, such as when a student visa is approved or when an international student officially starts a course of study. However, each ministry releases data at differing intervals. Australia’s Department of Education, for example, is well known for releasing new data almost every month. USCIS and IRCC tend to release data roughly quarterly, though both provide monthly breakdowns of their data in some cases.

Non-governmental entities generally do not collect data continuously. Instead, they may collect data annually, semiannually, or even less frequently. IIE’s Open Doors collects data annually for the previous academic year on international students and two years prior on U.S. study abroad students. The results for both are released every November.

The international aggregated sources receive data from national sources at widely varying times. As a result, there can be gaps in data, making comparison between or among countries challenging. Some countries don’t send data at all, often due to lack of resources for doing so. Even major host countries, notably China, send little if any data to UNESCO.

What type of student mobility data are included in the source?

Sources collect different types of student mobility data. One such breakdown is between inbound and outbound students—that is, those whom a country hosts versus those who leave the country to go study in other countries. Most government sources, such as IRCC, focus solely on inbound students—the international students hosted within the country— due to the organizations’ mandate and ability to collect data. Non-governmental organizations, such as IIE, often attempt to capture information on outbound (or “study abroad”) students. Many international sources, such as UNESCO UIS, capture both.

Another important breakdown addresses whether the data included degree-seekers, students studying abroad for credit back home, or those going abroad not explicitly for study but for a related purpose, such as research or internships:

- Degree mobility: captures data on students coming into a country or going abroad for pursuit of a full degree.

- Credit mobility: captures information on those abroad studying short-term for academic credit with their home institution, an arrangement often called “study abroad” (particularly in the U.S. and Canada) or “educational exchange.” The length of the study abroad opportunity typically can last anywhere from one year to as little as one week. Short-duration programs, such as faculty-led study tours, have become an increasingly popular option among students looking for an international experience. In most cases, the home institution is in the student’s country of origin, but that is not always the case. For example, a Vietnamese international student might be studying for a full degree in the U.S. but as part of the coursework studies in Costa Rica for one semester.

- Non-credit mobility: captures information on those who go abroad not for credit-earning coursework but for something highly related to a degree program, such as research, fieldwork, non-credit language study, an internship, or a volunteer opportunity. This may or may not be organized through the student’s education institution, and the parameters around this type of mobility can be blurry.

It’s important to know what each data source includes. Most governmental data sources will include both degree and credit mobility—students coming to study for a full degree or only as part of a short-term educational exchange. The dataset may or may not distinguish between these students, which is important to know if the distinction between such students is important for the data user’s purposes.

For outbound (“study abroad”) mobility, it’s easier for organizations to track credit mobility rather than degree mobility. IIE’s Open Doors, for example, examines only credit mobility for outbound students because it collects data through U.S. institutions, which track their outbound study abroad students and help them receive appropriate credits for their work abroad once they return. There is not a similar mechanism for U.S. degree-seekers going to other countries. That said, organizations such as IIE have attempted such research in the past, even if it is not an ongoing effort. Typically, the best way to find numbers on students from a particular country seeking full degrees abroad is to use UNESCO and sort the full global data by country of origin. UNESCO can also be used to find the numbers in a specific host country, or, in some cases, it may be better to go directly to the country’s national data source if available.

Non-credit mobility has been the least studied form of student mobility, largely because it is difficult to capture due to its amorphous nature. Nevertheless, some organizations, like IIE, have made one-off or periodic attempts to capture it.

Who is captured in the data source? How is “international student” defined?

Each data source may define the type of globally mobile student within the dataset differently. Chiefly, it’s important to recognize whether the source captures only data on international students in the strictest sense (based on that specific legal status) or on others who are not citizens of the host country. The latter could include permanent immigrants (such as permanent residents), temporary workers, and refugees or asylum seekers. The terms used can vary, from “foreign student” to a “nonresident” (sometimes “nonresident alien”), as some U.S. government sources use. It’s important to check the specific definition of the students for whom information is captured.

Most of the major student mobility data sources capture only data on international students as strictly defined by the host country. Here are the definitions of “international student” for the Big Four:

- United States: A non-immigrant resident holding an F-1, M-1, or certain types of J-1 (The J-1 visa is an exchange visa that includes but is not limited to students and can include individuals working in youth summer programs or working as au pairs, for example.)

- Canada: A temporary resident holding a study permit from a designated learning institution (DLI)

- United Kingdom: An individual on a Student visa

- Australia: An individual who is not an Australian citizen or permanent resident or who is not a citizen of New Zealand, studying in Australia on a temporary visa

Some countries make a distinction between international students enrolled in academic programs, such as at a university, versus those studying a trade or in a vocational school; there might also be distinct categorization for those attending language training. For example, in the U.S., M-1 visas are for international students studying in vocational education programs and may not be captured in some data sources, notably Open Doors.

Understanding the terminology used for international students helps in obtaining the right type of data. For example, one of the primary methods of obtaining data on international students in Canada is through IRCC data held on the Government of Canada’s Open Government Portal. But you won’t find any such dataset on “international students.” Instead, you need to search for “study permit holders.”

Does the data source include students studying online or at a branch campus abroad, or who are otherwise physically residing outside the host country?

Some universities and colleges have robust online programs that include significant numbers of students studying physically in other countries. (This was also true for many institutions during the pandemic. As a result, in the U.S., IIE temporarily included non-U.S. students studying at a U.S. institution online from elsewhere.) Other institutions have branch campuses or other such transnational programs that blur the line between international and domestic students. So, it’s important to ask: Does the data source include those not physically present in the institution’s country? The terminology for each country can vary. For example, in Australia, where such practices are very prominent, the term usually used to refer to students studying in Australian institutions but not physically in Australia is “offshore students.”

What levels of study are included in the dataset?

The focus of this article is postsecondary education, but some data sources do include primary and secondary students (“K-12 students” in the U.S. and Canada). IRCC’s study permit holder data includes students at all levels, including K-12 students. The ministry does provide some data broken down by level of study and other variables, such as country of citizenship and province or territory.

What about data on international students who are working?

Many host countries collect data and report on international students who are employed or participating in paid or unpaid internships during or immediately after their coursework. The specifics vary from country to country depending on how such opportunities for international students are structured and which government agencies are charged with overseeing such efforts. For example, in the U.S., the main work opportunities for most international students both during study (under Curricular Practical Training, or CPT) and after study (usually under Optional Practical Training, or OPT) are overseen by the student’s institution and reported via SEVIS. IIE’s Open Doors tracks students specifically for OPT but not CPT. By contrast, the main opportunity for international students to work in Canada after graduating from a Canadian institution is through the post-graduation work permit (PGWP). Students transfer to a new legal status in Canada, in contrast with U.S.-based international students under OPT, who remain on their student visa until their work opportunity ends. As a result, IRCC reports separate data on graduate students working under the PGWP, though data are relatively scant.

At some point, students who are able to and make the choice to stay and work beyond such opportunities in their new country transition to new legal statuses, such as the H-1B visa (a specialty-occupation temporary work visa) in the U.S., or directly to permanent residency in many countries. The data required to examine these individuals varies.

What about data beyond demographics?

While most international student datasets focus on numbers and demographic breakdowns, some datasets and other related research focus on such topics as the contributions of international students to national and local economies. For example, NAFSA: Association of International Educators, the main professional association for international educators in the U.S., maintains the International Student Economic Value Tool, which quantifies the dollar amounts that international students contribute to the U.S. at large, individual states, and congressional districts. Part of the intention behind this is to provide a tool for policy advocacy in Washington, D.C., and in state and local governments.

How can I contextualize international student numbers within the broader higher education context of a country?

Many countries collect and publish higher education data and other research. Each country assigns this function to different ministries or agencies. For example, in Canada, most such data are collected and published by Statistics Canada (StatCan), which is charged with data collection and research broadly for the country. In the U.S., this function falls under the Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), which runs a major higher education data bank known as IPEDS, the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System. StatCan does provide some data on international students, while IPEDS in the U.S. reports numbers of “nonresident” students, defined as “a person who is not a citizen or national of the United States and who is in this country on a visa or temporary basis and does not have the right to remain indefinitely.” This term likely encompasses mostly those on international student visas.

I will discuss some of these higher education data sources in Part 2 of this series.

How do I learn what I need to know about each individual dataset?

Each major data source typically provides a glossary, methodology section, and/or appendix that helps users understand the dataset. In Part 2 of this series, we will examine some of the major international and national data sources, including where to locate further such information for each.

It’s critical for users of student mobility data sources to understand these nuances in order to accurately and appropriately utilize the data. In the second part of this series, we will examine several prominent data sources.

-

What’s not talked about when you live overseas

The first time someone told me I was “too loud” in Latvia, I laughed. Not because it was funny, but because I genuinely hadn’t realized I was being loud. We were eating pizza one evening at Easy Wine in Riga, and despite being the only one not tipsy on the refreshments, I was still somehow the rowdiest at the table.

I shrank down an inch in my seat. The moment gave me pause. It was oddly familiar, like déjà vu. Everything around me felt almost known, just slightly askew, like it had been tilted on its axis.

The shame of taking up too much space? That I knew. But this time, it didn’t come from being Brown. It came from being American.

In the United States, my race is always top of mind. I’m a university student, and as a Government major, it’s a regular feature of my coursework. Having grown up in a nearly all-White town, I’ve been explaining my identity to others since I could talk.

With nearly two decades of practice under my belt, I’m well-versed in how my skin color and ancestry shape the world around me, and how to articulate that for others. So, the longer I spent in Riga, the more unsettled I felt by how absent race seemed from the conversation.

Conversations not had

Hours spent gazing out the windows of trolleybuses gliding through the city confirmed what I suspected: Riga is not very diverse. Among the small number of people of color I did see, most were other South Asians, like me. In the United States, race is an ever-present topic, whether it’s in political debates, academic syllabi or heated threads on X. In Latvia, it felt like race had slipped out of the cultural vocabulary altogether.

As part of my study abroad program, we often heard from expert guest lecturers. And as each one spoke, a quiet confusion grew inside me: Why is nobody talking about race? I started to feel like a foreign lunatic, playing an internal game of “spot the non-white person” on every street. But the more I searched, the more questions I had. Where was the discussion? Why wasn’t it happening?

So, I brought it up with a friend I’d made in my hostel. Arsh is an Indian student studying mechanical engineering at Riga Technical University. He had been living in the city since February. When I asked if he’d experienced discrimination as a visibly Punjabi Sikh, his answer surprised me.

“No,” he said.

And then he added something that completely shifted my perspective.

“Nobody talks.”

Silence and race

I’d known Latvians were famously quiet, but I’d never considered how that silence might shape their understanding and construction of race.

In the United States, your racial identity is often the first thing people ask about. Strangers want to know what you are and where you’re from. Race in America is personal, political and inescapable. The constant conversation can be both exhausting and empowering: it pushes systems to change, creates space for shared stories of resilience and holds people accountable.

But it also creates a kind of fatigue. As a person of color, you’re constantly on: explaining, reacting, defending. You’re visible, but often through a lens of trauma or tension.

In Latvia, it was different. What I came to think of as a kind of “quiet neutrality” reigned. People didn’t ask where I was from. They didn’t comment on my skin tone. They didn’t bring up diversity or inclusion, mainly because they weren’t speaking to me in the first place.

At first, that silence felt like relief. But eventually, it began to feel like an absence, because bias still exists, even if no one’s talking about it.

The power of passive racism

After speaking with Arsh, I turned to the Internet, searching for other South Asian perspectives on racism in Latvia. I found plenty.

One Quora user bluntly wrote, “Indians are treated like shit here in Latvia.” Another shared that she didn’t know if others felt negatively about her brown skin, but if they did, they didn’t confront her about it. A Redditor described being told to “go back to your own country.” These stories varied wildly from hate crimes to total indifference, but they painted a clear picture: racism existed here. It just didn’t look the same.

Curious to dig deeper, I reached out to Gokul from @lifeinlatviaa on Instagram. A popular Indian content creator who’s lived in Latvia for seven years, Gokul shares his takes on life in the Baltics. Many of his videos humorously cover topics of social culture, stereotypes, education and work. He also co-hosts the podcast Baltic Banter with Brigita Reisone.

When I asked Gokul about his experience, he described the racism in Latvia as mostly “passive.” Latvians, he said, are reserved. “If they don’t like something, they won’t be in your face about it,” he said.

Still, he shared more overt examples, like housing ads that openly say Indians need not call. He noted persistent stereotypes, too: that Brown people are dirty kebab shop owners or delivery drivers.

The familiarity of bias

None of this was unfamiliar to me. I’ve experienced housing discrimination. I’ve been called dirty by a White person. The common style of racism in Latvia was new to me: distant and quiet. In the United States, I once had a tween boy bike past me and mock an Indian accent — it was less traumatic than it was bizarre. There was certainly nothing subtle about it though.

Looking further, I found several reports from Latvian Public Broadcasting documenting hate crimes and prejudice against South Asians. So no, it’s not that racism doesn’t exist in Latvia. It’s that it shows up differently, and more importantly, it’s not widely discussed.

That difference matters.

Race is fluid and contextual; its meaning shifts with time, place and history. In the United States, racism is foundational. It began with colonization and slavery, extending through the systemic injustice known as Jim Crow in the 19th and 20th centuries, to modern-day Islamophobia and racial profiling by police. Racial violence and resistance are woven into the country’s DNA.

Latvia’s history tells a different story. Latvia is a nation shaped more by being colonized than by colonizing. Ethnic Latvians have fought for sovereignty under foreign rule, whether by Germans or Soviets. Today, its population is overwhelmingly White, and ethnic tensions tend to focus on Latvians and Russians, or Roma communities. Immigration is relatively new here, so the language to talk about race may simply not have developed yet.

And that brings me back to volume.

In the United States, being loud is often classed and racialized as “trashy,” especially when tied to communities of color. In Latvia, loudness is framed differently: it’s seen as a kind of cultural rudeness. It’s not about being Brown, it’s about being foreign. And because everyone is generally quieter, the social cues around race, identity and belonging shift, too.

Little things like volume, friendliness and eye contact build the scaffolding around how race is perceived in different societies. They may seem like surface-level quirks, but they shape deep-rooted assumptions.

And they remind us: racism may look different in various places, but it doesn’t disappear. It just changes form. And recognizing that change is the first step to dismantling it.

Questions to consider:

1. Why do many people outside the United States connect loudness with being American?

2. Why was the author troubled about the lack of conversation about racism in Latvia?

3. What kind of conversations do you have about race and do they make you feel more or less comfortable?

-

Can a podcast cross borders?

“To me the essential ingredient is that two persons or two teams from different countries collaborate, right?” Ricci said. “So who’s doing the podcast itself makes it really a cross-border operation.”

A podcast becomes cross-border, he said, when you bring different perspectives from different countries together in one story. There are two ways to make that story compelling to both the audiences and to Europe as a whole.

The first way, he said, is to have a strong story that articulates across borders and is relevant for two countries. It can be a very specific story that relates to feelings and notions interesting to anyone. The second way is to start from a general topic and then find a story within that topic.

“I’d really love that all podcasts speak to every audience we aim to target,” Ricci said. “I think it’s the biggest challenge to make sure that every podcast finds its audience in every national context.”

At WePod, the team divided the production process into stages.

First there was a pre-editorial stage where they brainstormed ideas. Then came a pre-production phase, where within the topic they reflected more concretely about the characters of each podcast.

“How do the different episodes talk to each other?” Ricci said.

Provide room for perspectives.

That was followed by the production phase. That involved going on the ground, setting up interviews and working on scripts and language transcriptions.

Finally, in the post-production phase everything textual became a finished podcast, ready to be promoted and distributed.

Caminero said that every podcast WePod did was produced in at least two languages, the first in the native language of the podcast producer and in English for a cross-border audience. “Obviously, this creates specific challenges because not all versions can be identical,” Caminero said. “You need to make room for adaptations.”

Ricci said that it was important in a big production like WePod, with people from different nationalities, to give people room to express themselves. “I think it takes time just to sit around the table, understand each other,” Ricci said.

This becomes important when you have deadlines and deliverables. “You’re pretty much kind of freaking out to meet everything, every deliverable you have to meet, every deadline,” Ricci said. If you try to impose a top down approach, it won’t work.

“So, I think it just takes a lot of talking before action,” Ricci said.

Questions to consider:

1. What does it mean to be cross-border?

2. How can a story that is interesting in one country have resonance in another?

3. Can you think of a topic important to your region that would also be important to people elsewhere?

-

With a passport, you should be able to vacation abroad. No?

On a weekday in Kampala, people line up early outside the embassies of European countries. Last year, almost 18,000 Ugandans joined these queues, according to an analysis by the Lago Collective. This year, I was one of them, folder in hand, hope in check.

Typically, those folders contain bank statements, proof of visa payment, job contracts, medical records, photos of family members, land titles, academic transcripts, flight reservations and detailed itineraries — each one meant to prove stability, legitimacy and belonging.

After paying to apply for a Schengen visa — which allows free travel between some 29 European countries for a limited time period — 36% of those Ugandans were rejected. Why? Mostly because embassy officials doubted the applicants would return home.

Each applicant must pay €90. That added up to more than €1.6 million that Ugandans paid Schengen countries last year, more than half a million of which was from applicants who ended up rejected.

The collective wager lost by Ugandan applicants was part of an estimated €60 million spent in Africa last year on Schengen visa applications that led nowhere. In fact, Africa alone accounted for nearly half of the €130 million the world paid in failed bids to enter the Schengen zone.

The Schengen gate

Tucked behind those numbers lies a quieter cost: missed opportunities for work or travel and the often-overlooked spending on legal consultations or third-party agencies hired to improve one’s chances. But more tellingly, there is a perception problem — wrapped in geopolitics and sealed with a stamp of denial.

“It’s like betting,” says Dr. Samuel Kazibwe, a Ugandan academic and policy analyst. “Nobody forces you to pay those fees, yet you know there are chances of rejection.”

One such story belongs to Fred Mwita Machage, a Tanzanian executive based in Uganda as human resource director at the country’s transitioning electricity distribution company. Machage thought he was just booking a summer getaway — a chance not only to unwind, but to affirm that someone like him, who had worked in Canada, had traveled to the United States and Great Britain, and, if you checked his profile, was “not a desperate traveler,” could move freely in the world. That belief, like the visa itself, did not survive the process.

He had planned a trip to France the past April. Round-trip tickets? Booked. Five-star hotel? Paid. Travel insurance? Secured. A $70,000 bank statement and a letter from his employer accompanied other documents in the application.

“They said I had not demonstrated financial capability,” Machage recalled, incredulous. “With my profile? That bank balance? It felt like an attack on my integrity.”

Worse, the rejection wasn’t delivered with civility: “The embassy staff were rude,” he said. “And they weren’t even European — they were African. One of the ladies looked like a Rwandan. It felt like being slapped by your own.”

Banned from travel

For Machage, the betrayal was not just bureaucratic — it seemed personal. He estimates his total loss at nearly $12,000, including tickets, hotel deposits, agent fees and visa costs. While he hopes for a refund, it’s understood that most travel agents don’t return payments; instead, they often suggest that you travel to a visa-free country.

That will likely get more difficult to do. This month, U.S. President Donald Trump issued a sweeping travel ban targeting twelve countries — seven in Africa. Somalia, Sudan, Chad and Eritrea faced full bans; Burundi, Sierra Leone and Togo, partial restrictions. The official reasons included high visa overstays, poor deportation cooperation from the home countries and weak systems for internal screening. And it ordered all U.S. embassies to stop issuing visas for students to come to the United States for education, although U.S. courts are considering the legality of that order.

For Machage, the rejection left him with a lingering sense of humiliation, though he found some small relief in a LinkedIn post where hundreds shared similar tales of visa rejection.

“I realised I wasn’t alone,” he said, “But the process still left me feeling worthless. Sorry to mention, but it’s a disgusting ordeal.”

I know exactly how Machage feels.

How to prove you will return home?

When I applied for a visa to the United Kingdom, I too was rejected. The refusal read:

“In light of all of the above, I am not satisfied as to your intentions in wishing to travel to the UK now. I am not satisfied that you are genuinely seeking entry for a purpose that is permitted by the visitor routes, not satisfied that you will leave the UK at the end of the visit.”

The “I am” who issued the rejection did not sign their name. Perhaps they knew I’d write this article and mention them. How easily the “I am” dismissed my ties, my plans, my story. Meanwhile, my British friend who had invited me was livid.

“It felt like they were questioning my judgment — about who I can and cannot welcome into my own home,” she said. She was angry not just on my behalf, but because she felt disregarded by her own government.

Captain Francis Babu, a former Ugandan minister and seasoned political commentator, doesn’t take visa rejections personally. He said the situation is shaped by global anxieties over the scale of emigration out of Africa into Europe that has taken place over the past decade.

“Because of the boat people going into Europe from Africa and many other countries and the wars in the Middle East, that has caused a little problem with immigration in most countries,” he said.

Needing, but rejecting immigrants

The issue is complicated. Babu said that these countries depend on the immigrants they are trying to keep out. In the United States, for example, farms depend on low-cost workers from South America.

“Most of those developed countries, because of their industries and having made money in the service industry, want people to do their menial jobs. So they bring people in and underpay them,” Babu said.

For Babu, even the application process feels unfair. “Even applying for the visa by itself is a tall order,” he said. “There are people here making money just to help you fill the form.”

While Babu highlights the systemic hypocrisies and challenges, others, like Kazibwe, see hope in a different approach — one rooted in political and economic organisation. Where people enjoy strong public services and can rely on a social safety net, there tends to be low emigration so countries are less hesitant to admit them.

“That’s why countries like Seychelles are not treated the same,” he explains. “It’s rare to see someone from Seychelles doing odd jobs in Europe, yet back home they enjoy free social services.”

For Kazibwe, the long-term fix is clear: “The solution lies in organising our countries politically and economically so that receiving countries no longer see us as flight risks,” he said.

Perhaps that is the hardest truth. Visa rejection is not just an administrative outcome, it’s a mirror: a verdict not simply on the individual but on the nation that issued their passport.

Back at the embassies, the queues remain. Young Ugandans, Ghanaians and Nigerians — some with degrees, others with desperation — wait in line, folders in hand, their hopes in check. And every rejection carries not just a denied trip, but a deeper question:

What does it mean when the world sees your passport and turns you away?

Questions to consider:

1. Why are so many Ugandans getting denied travel visas to Europe?

2. Why do some people think that the visa and immigration policies of many Western nations are hypocritical?

3. If you were to travel abroad, how would you prove that you didn’t intend to stay permanently in that country?

-

The guardians of the exosphere

Not many military forces have ranks and uniforms that were inspired by science fiction. The U.S. Space Force (USSF) has both. Their dress uniform is described by the U.S. Armed Forces Super Store as “a deep navy, representing the vastness of space” and the jacket’s buttons are diagonal and off centre with the logo of the Space Force.

Members of the Space Force are known as Guardians, a term that will be familiar to fans of the animated superhero series where extraterrestrial criminals unite to preserve the galaxy.

But the Space Force has a real and serious purpose. After being discussed for several decades, it was created in 2019 and tasked with protecting the United States from threats in space with the motto, “Semper supra,” which is Latin for “Always above.”

As the USSF mission statement explains, “From GPS to strategic warning and satellite communications, we defend the ultimate high ground.”

Despite its vast mission, there are fewer than 10,000 Guardians — enlisted women and men and officers — making it the smallest wing of the U.S. military.

Detecting missiles and other objects

Like all nations, the United States relies on critical infrastructure and everyday business that is now dependent on satellites which enable navigation, weather forecasting, earth observation, communication and intelligence.

Before the formation of the Space Force, monitoring satellites was part of the duties of the U.S. Air Force. Now the U.S. Space Force has taken over many of those duties and is dedicated solely to operating and protecting assets which operate in space. Their mission also includes operating the Ballistic Missile Early Warning System which is designed for advanced missile detection.

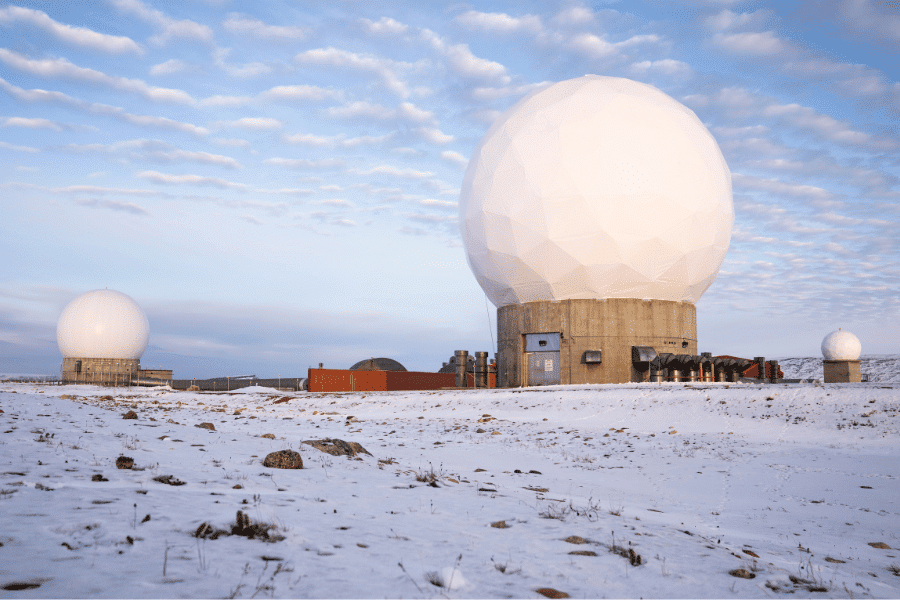

The USSF currently has six bases in the continental United States and one base outside of the country. Located in Greenland, it is its most northerly base. Previously known as Thule Base, in 2023 it reverted to its traditional name Pituffik.

In March 2025, Pituffik base hosted a visit by U.S. Vice President J.D. Vance following statements by President Trump that he wanted to “buy Greenland”.

Donald Trump was not the first American president who wanted to buy Greenland. In 1946 President Truman made a similar offer to Denmark, the colonial power. Denmark turned him down — the Greenlanders had no say in those days as a colony. Now Greenland is an autonomous territory of Denmark and all Greenlanders are Danish citizens.

Eyes on the skies

But even in 1946, there was already a U.S. base in Greenland, built during World War Two during the years that Denmark was occupied by Nazi Germany. Thule Base was America’s most northerly deepwater port and runway and supported Allied naval operations against the Nazi threat.

Now, 80 years on, the base can monitor not only space activities, but the expansion of Russian government activities in the Arctic region. Climate change is expected to enable an ice-free Northwest Passage in the coming decades when traffic in shipping could rival the Suez Canal.

Now, with the addition of the Space Force to Pituffik Base in Greenland, the sea sky as well as space will be closely monitored.

The location of Pituffik is not only strategically placed to keep an eye on Russian and Chinese space activities, but to monitor polar orbiting satellites. These observation satellites, which orbit north to south, make a full orbit every 92 minutes. In addition to civilian and scientific satellites, which provide data on land, sea and atmosphere, there are military satellites which are classified.

The vast majority of military satellites that are operated by the United States are believed to number around 250 which is more than the total of Russian and Chinese military satellites. Military observers believe many of these satellites are monitored from Pituffik.

Nobody wants a war in space.

The idea of a space force had been discussed for decades because “nobody wants a war in space” according to Major General John Shar, the commander of space operations for the U.S. Space Force. Shar compared the need for the United States to operate military space operations to ocean-going nations wanting a navy.

Several other countries agree. France, Canada and Japan have created their own versions of a space force to deter threats in space.

French President Macron announced the creation of a space command in 2019. The force is being established in tandem with the French Air Force. As one of the leading space nations in the world, the force will protect French satellites. French aerospace companies are currently designing a new generation of satellites reportedly designed to carry lasers and possibly even guns.

The Canadian Space Division, a division of the Royal Canadian Air Force, provides “space-based support of military operations” and “defending and protecting military space capabilities” according to their mission statements.

Japan’s Space Operations Group is part of the Japan Air and Space Self-Defense Force unit based in Tokyo. Japan, also a leading space nation, is building many earth observation and surveillance satellites. Many of their astronauts from JAXA, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, have flown missions on the International Space Station.

The Japanese have also taken on a wider mission, beyond a national military focus. They are enhancing their capability for Space Domain Awareness in order to focus on the increasing risk of collisions with satellites caused by space debris.

Earth’s satellite infrastructure can be substantially damaged by space debris orbiting at an average speed of 17,500 mph. It’s not only cyberattacks and targeted satellite destruction that can cause serious global disruption.

The United States, France, Japan and Canada point out that any new satellites and any activities from the respective space forces will stay within the strictures of the International Outer Space Treaty which outlaws testing nuclear weapons or weapons of mass destruction in space.

If space around the earth and beyond can remain a peaceful place, perhaps the designation of “Guardian” for the U.S. Space Force is appropriate.

Questions to consider:

1. In what ways does science fiction inspire ideas that are useful for humanity?

2. What should nations not be allowed to do in space?

3. Would you join a space force in your country to help monitor and protect space activities?

-

A history lesson on Europe for Donald Trump

“The European Union was formed in order to screw the United States, that’s the purpose of it.” So said U.S. President Donald Trump in February. He repeats this assertion whenever U.S.-European relations are a topic of debate.

Trump voiced his distorted view of the EU in his first term in office and picked it up again in the first three months of his second term, which began on January 20 and featured the start of a U.S. tariff war which up-ended international trade and shook an alliance dating back to the end of World War II.

What or who gave the U.S. president the idea that the EU was “formed to screw” the United States is something of a mystery. If he were a student in a history class, his professor would give him an F.

Trump’s claim does injustice to an institution that won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2012 in recognition for having, over six decades, “contributed to the advancement of peace and reconciliation, democracy and human rights in Europe” as the Nobel committee put it.

So, here is a brief guide to the creation of the EU, now the world’s largest trading bloc with a combined population of 448 million people, and the events that preceded its formal creation in 1952.

Next time you talk to Trump, feel free to brief him on it.

Staving off war

With Germans still clearing the ruins of the world war Adolf Hitler had started in 1939, far-sighted statesmen began thinking of ways to prevent a repeat of a conflict that killed 85 million people.

The foundation of what became a 28-country bloc lay in the reconciliation between France and Germany.

In his speech announcing the Nobel Prize, the chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, Thorbjorn Jagland, singled out then French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman for presenting a plan to form a coal and steel community with Germany despite the long animosity between the two nations; in the space of 70 years, France and Germany had waged three wars against each other. That was in May 1950.

As the Nobel chairman put it, the Schuman plan “laid the very foundation for European integration.”

He added: “The reconciliation between Germany and France is probably the most dramatic example in history to show that war and conflict can be turned so rapidly into peace and cooperation.”

From enemies into partners

In years of negotiations, the coal and steel community, known as Montanunion in Germany, grew from two — France and Germany — to six with the addition of Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg. The union was formalized with a treaty in Paris in 1951 and came into existence a year later.

The coal and steel community was the first step on a long road towards European integration. It was encouraged by the United States through a comprehensive and costly programme to rebuild war-shattered Europe.

Known as the Marshall Plan, named after U.S. Secretary of State George C. Marshall, the programme provided $12 billion (the equivalent of more than $150 billion today) for the rebuilding of Western Europe. It was part of President Harry Truman’s policy of boosting democratic and capitalist economies in the devastated region.

From the six-nation beginning, the process of European integration steadily gained momentum through successive treaties and expansions. Milestones included the creation of the European Economic Community and European Atomic Energy Community.

In 1986, the Single European Act paved the way to an internal market without trade barriers, an aim achieved in 1992. Seven years later, integration tightened with the adoption of a common currency, the Euro. Used by 20 of the 27 member states, it accounts for about 20% of all international transactions.

Brexiting out

One nation that held out against the Euro was the United Kingdom. It would later withdraw from the EU entirely after the 2016 “Brexit” referendum led by politicians who claimed that rules made by the EU could infringe on British sovereignty.

Many economists at the time described Brexit as a self-inflicted wound and opinion polls now show that the majority of Britons regret having left the union.

In decades of often arduous, detail-driven negotiations on European integration, including visa-free movement from one country to the other, no U.S. president ever saw the EU as a “foe” bent on “screwing” America. That is, until Donald Trump first won office in 2017 and then again in 2024.

What bothers him is a trade imbalance; the EU sells more to the United States than the other way around; he has been particularly vocal about German cars imported into the United States.

Early in his first term, the Wall Street Journal quoted him as complaining that “when you walk down Fifth Avenue (in New York), everybody has a Mercedes-Benz parked in front of his house. How many Chevrolets do you see in Germany? Not many, maybe none, you don’t see anything at all over there. It’s a one-way street.”

This appears to be one of the reasons why Trump imposed a 25% tariff, or import duty, on foreign cars when he declared a global tariff war on April 2.

His tariff decisions, implemented by Executive Order rather than legislation, caused deep dismay around the world and upended not only trade relations but also cast doubt on the durability of what is usually termed the rules-based international order.

That refers to the rules and alliances set up, and long promoted by the United States. For a concise assessment of the state of this system, listen to the highest-ranking official of the European Union: “The West as we knew it no longer exists.”

So said Ursula von der Leyen, president of the Brussels-based European Commission, the main executive body of the EU. Its top diplomat, Kaja Kallas, a former Prime Minister of Estonia, was even blunter: “The free world needs a new leader.”

Questions to consider:

1. Why was the European Union formed in the first place?

2. How can trade serve to keep the peace?

3. In what ways do nations benefit by partnering with other countries?