Can you tell the difference between a rumor and fact?

Let’s start with gossip. That’s where you talk or chat with people about other people. We do this all the time, right? Something becomes a rumor when you or someone else learn something specific through all the chit chat and then pass it on, through chats with other people or through social media.

A rumor can be about anyone and anything. The more nasty or naughty the tidbit, the greater the chance people will pass it on. When enough people spread it, it becomes viral. That’s where it seems to take on a life of its own.

A fact is something that can be proven or disproven. The thing is, both fact and rumor can be accepted as a sort of truth. In the classic song “The Boxer,” the American musician Paul Simon once sang, “a man hears what he wants to hear and disregards the rest.”

Once a piece of information has gone viral, whether fact or fiction, it is difficult to convince people who have accepted it that it isn’t true.

Fact and fiction

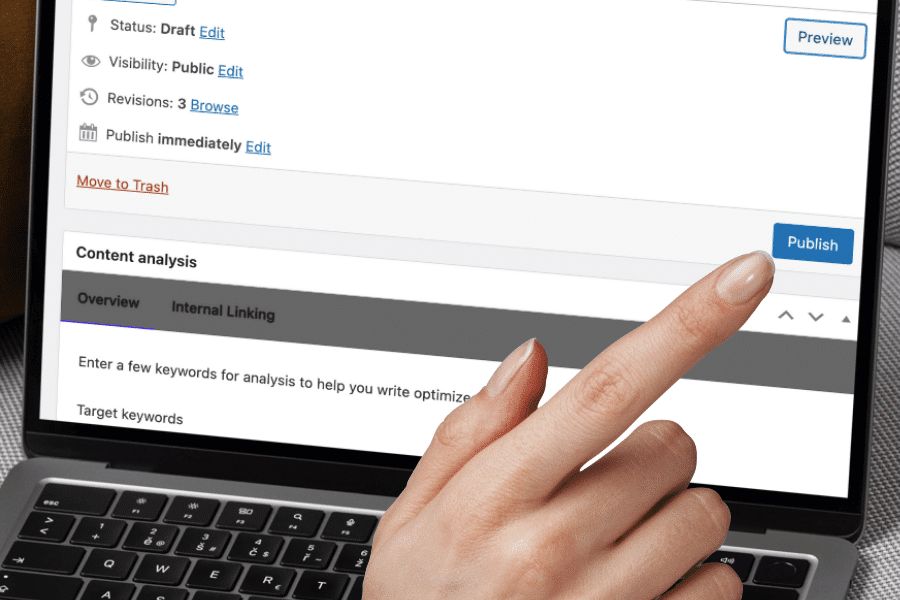

That’s why it is important — if you care about truth, that is — to determine whether or not a rumor is based on fact before you pass it on. That’s what ethical journalists do. Reporting is about finding evidence that can show whether something is true. Without evidence, journalists shouldn’t report something, or if they do they must make sure their readers or listeners understand that the information is based on speculation or unproven rumor.

There are two types of evidence they will look for: direct evidence and indirect evidence. The first is information you get first-hand — you experience or observe something yourself. All else is indirect. Rumor is third-hand: someone heard something from someone who heard it from the person who experienced it.

Most times you don’t know how many “hands” information has been through before it comes to you. Understand that in general, stories change every time they pass from one person to another.

If you don’t want to become a source of misinformation, then before you tell a story or pass on some piece of information, ask yourself these questions:

→ How do I know it?

→ Where did I get that information and do I know where that person or source got it?

→ Can I trace the information back to the original source?

→ What don’t I know about this?

Original and secondary sources

An original source might be yourself, if you were there when something happened. It might be a story told you by someone who was there when something happened — an eyewitness. It might be a report or study authored by someone or a group of people who gathered the data themselves.

Keep in mind though, that people see and experience things differently and two people who are eyewitness to the same event might have remarkably different memories of that event. How they tell a story often depends on their perspective and that often depends on how they relate to the people involved.

If you grow up with dogs, then when you see a big dog barking you might interpret that as the dog wants to play. But if you have been bitten by a dog, then a big dog barking seems threatening. Same dog, same circumstance, but contrasting perspectives based on your previous experience.

Pretty much everything else is second-hand: A report that gets its information from data collected elsewhere or from a study done by other researchers; a story told to you by someone who spoke to the person who experienced it.

But how do videos come into play? You see a video taken by someone else. That’s second-hand. But don’t you see what the person who took the video sees? Isn’t that almost the same as being an eyewitness?

Not really. Consider this. Someone tells you about an event. You say: “How do you know that happened?” They say: “I was there. I saw it.” That’s pretty convincing. Now, if they say: “I saw the video.” That’s isn’t as convincing. Why? Because you know that the video might not have shown all of what happened. It might have left out something significant. It might even have been edited or doctored in some way.

Is there evidence?

Alone, any one source of information might not be convincing, even eyewitness testimony. That’s why when ethical reporters are making accusations in a story or on a podcast, they provide multiple, different types of evidence — a story from an eyewitness, bolstered by an email sent to the person, along with a video, and data from a report.

It’s kind of like those scenes in murder mysteries where someone has to provide a solid alibi. They can say they were with their spouse, but do you believe the spouse?

If they were caught on CCTV, that’s pretty convincing. Oh, there’s that parking ticket they got when they were at the movies. And in their coat pocket is the receipt for the popcorn and soda they bought with a date and time on it.

Now, you don’t have to provide all that evidence every time you pass on a story you heard or read. If that were a requirement, conversations would turn really dull. We are all storytellers and we are geared to entertain. That means that when we tell a story we want to make it a good one. We exaggerate a little. We emphasize some parts and not others.

The goal here isn’t to take that fun away. But we do have a worldwide problem of misinformation and disinformation.

Do you want to be part of that problem or part of a solution? If the latter, all you have to do is this: Recognize what you actually know and separate it in your head from what you heard or saw second hand (from a video or photo or documentary) and let people know where you got that information so they can know.

Don’t pass on information as true when it might not be true or if it is only partially true. Don’t pretend to be more authoritative than you are.

And perhaps most important: What you don’t know might be as important as what you do know.

Questions to consider:

1. What is an example of an original source?

2. Why should you not totally trust information from a video?

3. Can you think of a a time when your memory of an event differed from that of someone else who was there?