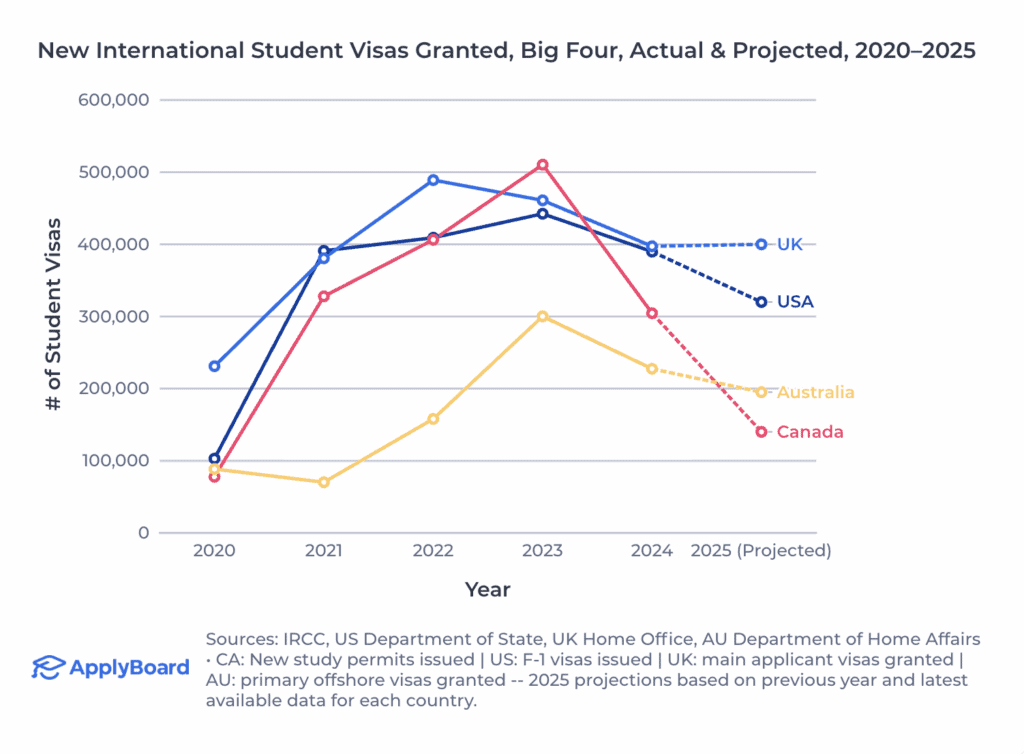

The study, conducted by ApplyBoard, highlighted the absence of consistent communication around policy shifts in Canada, the US, UK and Australia last year – a persistent issue that it said would likely drive subdued demand across the four in 2026.

Although a slowdown in Canada was widely expected, ApplyBoard CEO Meti Basiri said the projected 54% decline in new study permits this year was “stark”, setting Canada on track to issue the lowest total international study visas of the big four in 2025.

As per ApplyBoard estimates, Canada will see the sharpest drop in new international students, granting just 80,000 postsecondary study visas this year, while the US and Australia are set to see less dramatic drops.

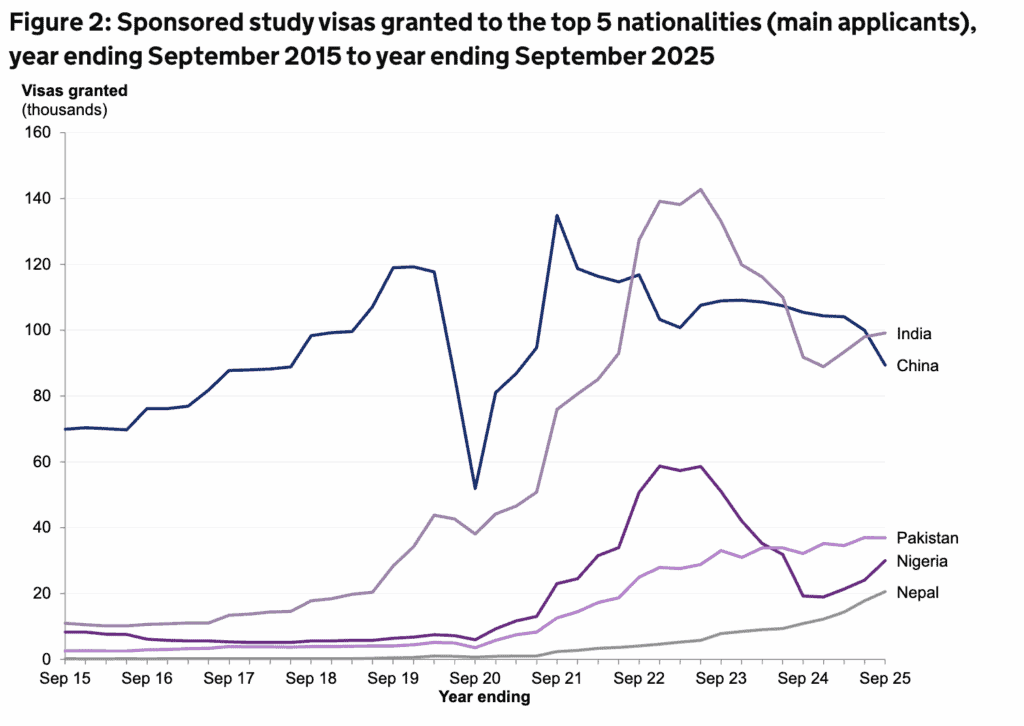

The UK – the only ‘big four’ destination without a projected decline – is on track to maintain 2024 study visa issuance levels, in line new Home Office data showing a 7% increase in applications this year, though this could be slightly tempered by pending changes proposed by the immigration white paper.

Basiri said Canada’s projected 80,000 new study permits would mark the lowest number of post-secondary approvals for the past decade, including during the pandemic. Elsewhere, stakeholders have raised concerns about the country’s plummeting study visa approval rate, which dropped below 40% this year.

As the government pursues its goal of reducing Canada’s temporary resident population to below 5% by the end of 2027, the sector has been hit with two years of federal policy changes leading to lower application volumes, lower approval rates, and a higher proportion of onshore extensions.

At the same time, in a recent student survey, Canada scored highly on welcomeness – with roughly 71% of students viewing it as open, safe and welcoming – but it also had one of the highest levels of disagreement for this metric.

“That polarisation suggests that international students are picking up on the tension between Canada’s long-standing reputation, and the current reality of caps, more limited work rights, and public debate that often links international students to housing and affordability pressures,” said Basiri.

The report highlighted the impact of domestic political pressures around housing and net migration causing governments to tighten visa requirements, impose caps, reduce post-study work streams and raise compliance thresholds.

However, Basiri said the deciding factor for students increasingly came down to financial considerations, including the cost of study, cost of living and the ability to work during and after their studies.

“While political decisions set the rules of the game, affordability is often the filter through which students evaluate those rules – making it the more powerful force driving more students to consider more financially accessible destinations across Europe and the Asia-Pacific region,” he said.

“The speed at which alternative destinations are stepping up is remarkable,” Basiri added, highlighting the efforts of Germany, France, Spain, New Zealand, South Korea, and the UAE establishing clearer career pathways and expanding work rights, among other factors to boost internationalisation.

The speed at which alternative destinations are stepping up is remarkable

Meti Basiri, ApplyBoard

While traditional destinations are experiencing dips in demand, overall international student mobility continues to flourish, with more than 10 million students expected to study outside their home countries by the end of the decade, up from 6.9m in 2024.

The emergence of alternative destinations has not gone unnoticed, with another recent report tracking the rise of education “powerhouses” across Asia, fuelled by more English-taught programs, growing job opportunities and affordable study options.

Meanwhile, Europe is catching students’ attention, with European countries accounting for eight out of the top 10 destinations – outside the big four, Germany and Ireland – in ApplyBoard’s recent survey of student advisors.

Basiri identified Germany and Spain as the destinations poised for the most growth next year: “Each offers a strong combination of affordability, workforce alignment, and clear post-study pathways that align with student priorities … Together, they are helping to shape the next wave of student mobility,” he said.

The rise of Germany in recent years has been widely reported on across the sector, with international enrolments on track to surpass 400,000 last year. What’s more, two-thirds of Germany’s international students say they intend to stay and work in the country after graduating.

Meanwhile, this summer the Spanish government authorised a policy to fast-track international students impacted by US visa restrictions, alongside authorising part-time work for students this academic year.

Coupled with previous measures relaxing visa requirements and new work and dependents rights, Spain is becoming “one of the most student-friendly destinations in Europe” said Basiri, noting its heightened appeal among Latin American students due to language and cultural affinities, as well as streamlined routes into the workforce.