There’s an absolutely jaw-dropping passage in this year’s IFS Annual report on education spending in England.

In total, we now estimate that under current policy, the long-run cost of issuing loans to the 2022–23 starting cohort will be negative (–£0.8 billion), with graduates repaying more than they borrowed, when future repayments are adjusted for inflation.

In other words, we’ve gone from government suggesting that the state would subsidise undergraduate student loans by about 45p in the pound, to making a profit on them for that cohort.

Put another way, we’ve stealthily moved from a £4,950 (graduates) £4,050 (state) cost sharing arrangement in the headline tuition fee to a £9,606 (graduates) -£356 (state) split for that 2022 cohort.

“Tuition fees almost doubled in a decade on average” is not the story that universities tend to tell. But it is, according to the IFS, the reality.

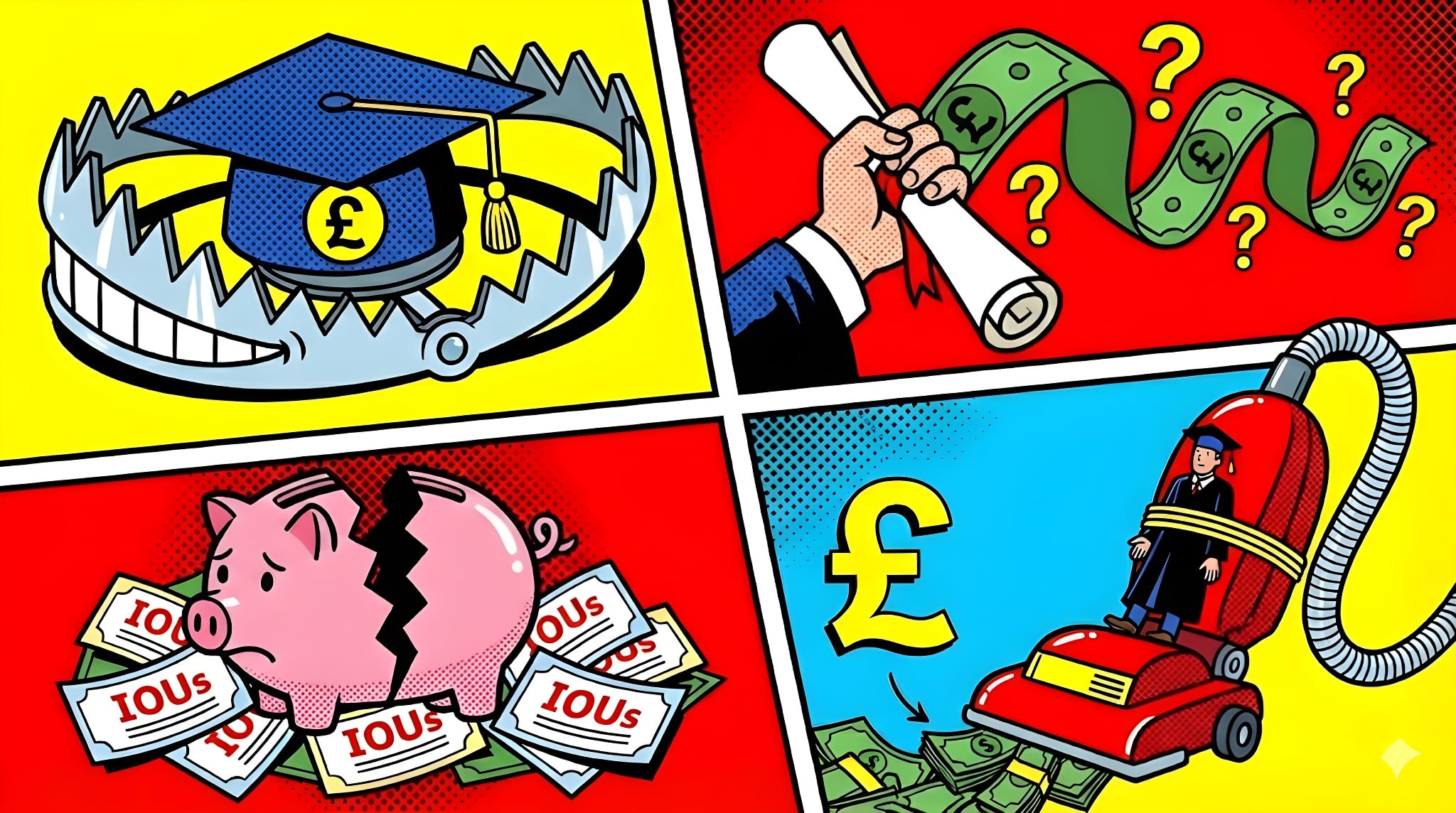

Floods of tears

I like to think of the English student loan system as an onion with several layers, all of which make people cry.

On the surface there’s the headline fee, even though you might not pay that in the end. Below that there’s the “debt” figure that appears on your student loan statement, which is impacted by interest. You may well not pay that either, because student loans are written off after a certain number of years.

What really matters – several layers down – is the repayment terms. And that 2022 cohort have been double whacked.

Back in 2022, then universities minister Michelle Donelan announced a response to the Augar review, in which she was “delighted to announce” that she would deliver the Conservatives’ manifesto commitment to address the interest rates on student loans by reducing it to down to inflation only.

To pay for that reduction in eventual repayments, the new “Plan 5” was only going to write off loans after 40 rather than 30 years, and the repayment threshold would be set at £25,000, rising with inflation from April 2027 onwards.

But for 2022 starters on the old Plan 2 – the ones with interest rates at RPI-X plus 3 per cent – she also announced a decision to hold the Plan 2 repayment threshold at £27,295 until April 2025.

Fixing the threshold in cash terms was going to pull more borrowers into repayment and increase repayments year by year, which at the time the IFS said would mean nearly all borrowers would lose from the reform, with graduates with middling earnings set to lose the most:

![]()

And on the Plan 5 changes, the IFS said that cutting the repayment threshold and then freezing it (and changing how it is uprated thereafter), extending the repayment term from 30 to 40 years, and cutting the interest rate to inflation only would result in graduates with lower-middling earnings losing the most, while the highest earners would gain substantially:

![]()

The changes were, in other words, both stealthy and regressive.

The Pink Panther meets reverse Robin Hood

In 2022, Labour’s then Shadow Secretary of Education, Bridget Phillipson, said:

The Tories are delivering another stealth tax for new graduates starting out on their working lives which will hit those on low incomes hardest.

In her September 2023 speech to Universities UK conference, she said:

…student finance will be the first to see change, although by no means the last. We have been clear about that from opposition and we will be clear about that from power.

She was concerned about distributional impact:

The Tory changes which bite a first cohort of students this autumn are desperately unfair. More unfair on women. More unfair on low earners. More unfair, not just for a few short years, but all through a generation of working lives, with higher loan repayments eating away at pay for young graduates just as they’re starting out on their working lives, and deterring older learners from retraining or upskilling.

And we got commitments on change, and the speed of that change:

Future nursing graduates repaying about £60 more a month. The Tories’ choices are hammering the next generation of nurses, teachers and social workers; of engineers, of designers and researchers. It’s wrong. It’s unsustainable. And it’s going to change. And why I tell you today that the next Labour government, whenever it is elected, will move swiftly to right these wrongs.

In an interview with the Telegraph on 7th October 2023, she doubled down – saying that the new system is “going to become more regressive for lower middle earners” and:

…is not a sustainable system… we will have to confront that if we win the election.

And then on BBC Question Time in May 2024, she said:

I am determined that we can deliver a more progressive system without any more spending or borrowing.

But rather than deliver on that raft of promises, they’ve done the stealth and regressive thing again.

Blink and you missed it

Buried in the Budget in November, chancellor Rachel Reeves announced a freeze in the Plan 2 repayment threshold – it is to be frozen at its April 2026 level (£29,385) for three years.

There’s been a dribble of political press coverage ever since, focussed mainly on the plight of young graduates and the rise in the minimum wage eroding the graduate premium.

But (as the IFS point out in their annual report), something else was hiding. As well as the repayment threshold, Plan 2 interest-rate thresholds (the lower and higher thresholds that determine whether interest is charged at RPI, RPI plus 3 per cent, or a sliding rate between) are also to be frozen for three years for Plan 2 grads, at their April 2026 levels (£29,385 and £52,885).

This was not mentioned at all in the Budget document or speech, but did appear deep in OBR costings – and was subsequently confirmed to the IFS.

For that 2022 cohort, it means many more borrowers can expect to make repayments for longer, and an increase in the interest accrued. And the IFS says that the latter will have nearly as substantial an impact on lifetime loan repayments as the repayment threshold freeze, and will affect a different set of borrowers.

Here’s how the IFS calculate the distributional impacts of the changes for that 2022 cohort:

![]()

I’m not sure I could have invented a stealthier, or more regressive change if I tried.

One thing I note in passing is that the changes to both Plan 2 and Plan 5 are usually accompanied by an equality impact assessment – that hasn’t appeared at all – and the changes to Plan 2 are actually in theory joint changes that require both Welsh and English ministers to lay them jointly.

Not only has the secondary legislation not appeared, there’s no word yet on whether Welsh ministers are accepting them. And if and when we do get that EIA, let’s not expect much light – given that DfE doesn’t even bother to break down estimates of loan borrower numbers by the rate of interest paid.

It couldn’t be, could it, that a Treasury desperate to make its excel sheets add up having ruled out income tax increases just decided at the last minute to raid the budgets of Plan 2 graduates in the hope that nobody would notice? Could it?

The student interest (rate)

Of course being less “stealthy” does require someone to peel back the onion layers – never the Treasury’s strong suit – and pretty much the only opinion in the Gordian knot on making changes that are less regressive involves higher interest rates. It’s only by asking both Plan 2 and Plan 5 high-earning graduates to pay back more (by paying their “graduate tax” for longer) that you can do it.

But the political problem of increasing interest rates is significant – because everyone hates interest, especially when it adds to that (often irrelevant) balance figure. And because the system is still labelled as a loan and sold as a loan, and because therefore people assume (hope?) they’ll pay it back some day, more interest sounds bad.

For that Plan 2 mob, if government had just whacked interest up to a gazillion per cent, all of them would be paying graduate tax for 30 years – with only the most successful graduates paying more. But in that “it’s a bit like a loan and it’s a bit like a tax” dance, tilting the see-saw towards loan will always mean it ends up more regressive.

In a debate just before Christmas on student loans, Treasury minister Torsten Bell said that there had been a “cross-party consensus” that a fairer system of university funding will require a “lower net contribution to universities from the taxpayer”.

In 2025, 34 per cent of loan debt for full-time plan 2 graduates was forecast not to be repaid, so what we are talking about is still substantive.

The Department for Education’s calculation of the RAB charge differs a little from the way the Treasury calculates the subsidy in the accounts every year, and both differ a little from the way the IFS calculates things.

But Bell was actually referring to the tiny number of students left getting a new Plan 2 loan this year. And at what point has there been a “cross-party consensus” that the subsidy for 2022 entrants should be minus 4 per cent?

More importantly, why on earth should students who are paying more but getting less be expected to fund the raft of public “goods” expected from their private debt, when the only contribution the state will make for that cohort is running the loan scheme?

That’s livin’ all wrong

Elsewhere in the report, there’s analysis on the international levy and the proposed maintenance grants, and a pretty shocking graph on the decline in maintenance loan entitlements per year by household income:

![]()

The upshot there is that despite the government trumpeting that maintenance would be index-increased along with fees, by 2029–30 IFS expects that some students – those with household residual incomes of between £23,400 and £61,400 – may be able to borrow less in real terms than they would be entitled to this academic year, with the largest falls of over £1,100 (around a sixth) for those with household incomes of around £53,000.

That’s the refusal to uprate the household income threshold since its announcement in 2007 – which will see fewer and fewer students getting the maximum loan as the Parliament continues.

(Astonishingly, the government’s guidance for the 2025-26 iteration of the Turing scheme now defines “students from disadvantaged backgrounds” as someone with an annual household income of £35,000 or less, up from £25,000 last year. They’d have to be able to afford to participate HE in the first place, mind)

I’ve not rehearsed here the stealthy abolition of the protection you currently get on the parental contribution when more than one child is in higher education, the miserable state of PG loans (both in repayment and value terms), the shocking state of the level of support for student parents, the slow shift of DSA onto universities’ budgets, the shameful way we treat those on universal credit that are in full-time education, or the ways in which this reduction in the spending envelope will impact the “equivalence” envelope for the loans systems in devolved nations.

But I will rehearse how far Labour has fallen on student financial support.

Those were the days

In January 2004, partly to sweeten the pill over proposals to raise fees to £3,000, then Secretary of State for Education and Skills (Charles Clarke) announced a new package of student finance to ensure that “disadvantaged students will get financial support to study what they want, where they want”.

From September 2006 there were to be new higher education grants – and maintenance loans were to be raised to the median level of students’ basic living costs as reported by the student income and expenditure survey – to ensure that students have “enough money to meet their basic living costs while studying”.

The aspiration was to move to a position where the maintenance loan was “no longer means-tested” and available in full to all full-time undergraduates, so students would be treated “as financially independent from the age of 18”. Graduates were to get the optyion of a repayment holiday to ease the burden as they moved into the labour market. And the new Office for Fair Access was to be required to issue additional bursaries to students.

By July 2007, the then new Secretary of State for Innovation, Universities and Skills, John Denham, went further with new reforms to support for (undergraduate) students in higher education (from England) – to recognise that hard-working families on modest incomes had “concerns about the affordability of university study”.

The rhetorical flourishes are all pretty similar to those we hear today – but we should, for the sake of argument, look at what has happened since. Even though by the time the changes were implemented the SIES data was a few years old, at least the “we’ll fund basic living costs” principle was there.

In 2007 DIUS ministers had not been able to persuade the Treasury to abandon means testing – but full grants were to be made available to new students from families with incomes of up to £25,000, compared with £18,360 – along with minimum £310 bursaries from higher education institutions.

The announcement was accompanied by a document with some handy case studies – Student A, whose parents who had a combined household income of £50,000 and who had a brother who already studying at university; Student B, from from a single parent family with a household income of £20,000; and Student C, living with both parents who had a residual household income of £25,000.

Here’s what they were entitled to at the time (away from home, outside of London):

|

Student A |

Student B |

Student C |

| Household income |

50000 |

20000 |

25000 |

| Grant |

560 |

2825 |

2825 |

| Loan |

4070 |

3370 |

3370 |

| Guaranteed bursary |

|

310 |

310 |

| Total |

4630 |

6505 |

6505 |

That £25,000 household income threshold hasn’t moved since, there’s now no grants (and the ones that are coming derisory), nobody’s guaranteed a bursary (and most universities are reducing their spend on bursaries) and both prices and incomes have risen since.

So to see how far things have fallen, let’s see what those three students were entitled to last year. Student A’s parents now earn around £83,500; Student B’s single parent family now earns around £33,400; and Student C’s parents earn around £41,750.

|

Student A |

Student B |

Student C |

| Household income |

83500 |

33400 |

41750 |

| Maintenance loan |

4767 |

9497 |

8035 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Now let’s adjust those totals to 2008 prices (RPI) to look what what they’re worth:

|

Student A |

Student B |

Student C |

| Maintenance loan |

2569 |

5117 |

4330 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

And let’s do the comparison in 2008 prices, which shakes down as follows:

|

Student A |

Student B |

Student C |

| 2008 |

4630 |

6505 |

6505 |

| 2024 |

2569 |

5117 |

4330 |

| Inc/Dec |

-2061 |

-1388 |

-2175 |

|

-45% |

-22% |

-34% |

|

|

|

|

Finally, let’s take HEPI’s minimum income standard from 2024 as a way of judging the gap between state (loan) support and what students need – the implied parental/part-time work contribution – we can see the problem in another way as follows (all figures adjusted for 2024 prices via RPI):

|

Student A |

Student B |

Student C |

| 2008 |

£10,040 short |

£6,561 short |

£6,561 short |

| 2024 |

£13,865 short |

£10,135 short |

£10,598 short |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Why are two-thirds of students working? Why is attendance becoming so hard to secure? Why are mental health problems rocketing? Why are more and more students choosing to live at home, restricting their subject and institution choices? Why is youth despair at record levels? Sometimes the answers are pretty obvious, really.

Levelling down

Why is all of this happening? An observation on borrowing, and two final graphs from the IFS report tell the real story.

First, borrowing. Back in 2021, when the government borrowed money on the bond markets to fund student loans, it could do so very cheaply in real terms because interest rates were low and inflation was expected to be higher – so investors were effectively accepting a loss after inflation.

In practical terms, markets were willing to pay the government about 1.4 per cent a year, after inflation, just to lend it money.

But today – mainly because Germany is now back in the borrowing game – the situation has reversed. Interest rates on long-term government borrowing are much higher, while expected inflation over the same period is lower, so borrowing now costs the government money in real terms.

Using the same measure, the government is now paying investors roughly 2.3 per cent a year, after inflation, to finance new student loan borrowing. The swing from a negative to a positive real cost is large, and it materially changes how expensive student loans are for the public finances – just not in way that is especially (or, in fact, at all) transparent.

And then there’s the IFS education spending squid:

![]()

To be fair to ministers, it’s true that the research says you can make the most difference on life chances by investing in early years. Substantially, coupled with investment in NEETs and those in further education, we are seeing ministerial priorities manifest over time:

![]()

But none of the research that underpins those priorities weighs up cutting the spend on HE to fund everything else, which will mean spend per student will soon be just 44 per cent greater than primary school spending per pupil, having been almost four times greater in the early 1990s.

More importantly, there simply hasn’t been a proper debate about the share of that blue line that should be paid by the state versus the share (eventually) paid by graduates since the grand promises of the early 2010s.

We now, by some very substantial measure, have easily the most expensive state higher education system in Europe from a student/graduate point of view – a system which see the recipients paying more and more, getting less and less, and having less money (and therefore time) to participate in what’s there – resulting in worse educational outcomes (as measured internationally), and worse mental health.

And it’s a system in which, thanks to graphs like this and the regressive nature of the loans changes described above, where distributionally, the losers are also those least likely to benefit from the great boomer wealth transfer that is coming in the next decade:

![]()

Add it all up, and it means that the role that higher education once thought it played in social mobility is pretty much dead. From here, talk like that I’ll be an angel then things can only get worse.