NORMAN, Okla. — Sometimes, Jakob Topper teaches his Christian faith to his 6-year-old daughter using children’s Bible stories illustrated with teddy bears. Other days, he might use her kid-friendly Bible featuring Precious Moments figures as characters. One thing he knows for sure: The King James version is not on the reading list, given some of its adult themes of sexual assault and incest.

As a parent and a Baptist pastor, Topper opposes Oklahoma’s state superintendent of public instruction’s mandate to put a King James Version Bible in every grade 5–12 classroom. The father of three is also not keen on the state’s newly proposed social studies standards that would require biblical lessons starting in first grade.

“I want the Bible taught to my daughter, and I want to be the one who chooses how that’s done,” said Topper, who also has a 1-year-old and a 3-year-old and is pastor of NorthHaven Church in Norman, a university town. “If we’re talking about parental choice, that’s my choice. I don’t want it to be farmed out to anyone else.”

Norman, a central Oklahoman city of about 130,000, is an epicenter of resistance to the Bible mandate that the state superintendent of public instruction, Ryan Walters, announced last June. Opposition here has come from pastors, religion professors, students, parents, teachers, school board members and the school district superintendent, among others. The prevailing philosophy among Norman residents, who are predominantly Christian, is that they do not want the state — and namely, Walters — mandating how children should be taught scriptures. They want their children to learn from holy books at home or in church.

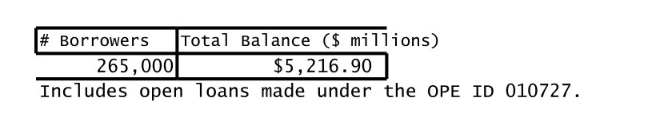

Many residents see Walters’s pitch as a play for national attention, given his abundance of social media posts praising Donald Trump, who campaigned on returning prayer to schools and as president has established a White House Faith Office and a task force to root out “anti-Christian bias.” In September, Walters proposed spending $3 million to buy 55,000 copies of the Bible that has been endorsed by the president and for which he receives royalties. More recently, Walters — who in February clashed with his state’s governor for proposing that public schools track students’ immigration statuses — made media lists as a possible candidate for Trump’s education secretary. He was not picked.

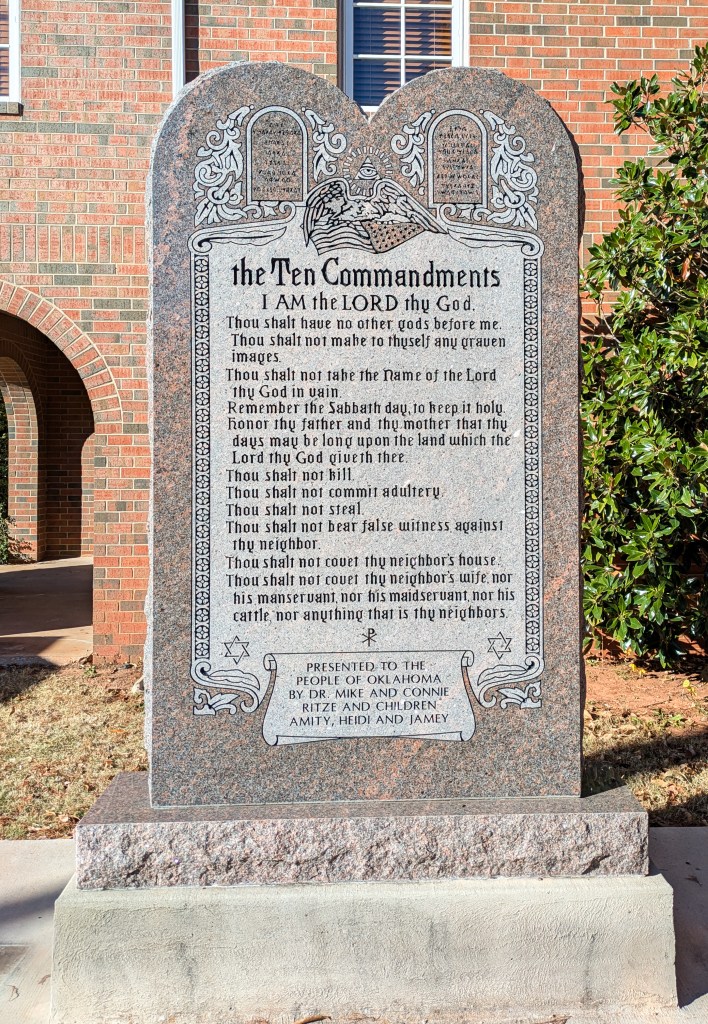

But beyond Walter’s national aspirations, the Bible mandate also seems like an attempt at one-upmanship, with other states angling to infuse Christianity into public schools. Louisiana, for instance, is in a court battle over its push for Ten Commandments posters in schools. Texas fought off Democratic opposition to approve an optional Bible-infused curriculum and financial incentives for school districts that use the materials. A slew of states have passed or promoted similar measures, including ones allowing chaplains to act as counselors in schools. Unsurprisingly, Walters, too, has advocated for displaying the Ten Commandments in every classroom and also has backed the conversion of a private virtual Catholic school into a charter school; the Supreme Court plans to hear oral arguments on the case on April 30.

It goes without saying that Walters’s crusade is multifaceted. But fundamentally, all of his efforts amount to teaching the Bible “in inappropriate ways in public schools,” said Amanda Tyler, author of “How to End Christian Nationalism” and executive director of the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty, a Washington, DC–based organization of attorneys, ministers, and others who advocate for religious freedom. “He’s saying you can’t be a good American citizen if you don’t understand the Bible,” she added. “It’s this merger of American and Christian identities, the idea that only Christians are true Americans.”

On March 10, the Oklahoma Supreme Court dealt a blow to Walters’s plans: It issued a temporary stay prohibiting the state’s department of education from purchasing 55,000 Bibles with certain characteristics and from buying Bible-infused lessons and material for elementary schools.

The stay stems from a lawsuit led by Americans United for Separation of Church and State on behalf of 32 plaintiffs, including parents, clergy, students and teachers. The group, which is suing Walters, claims the Bible mandate violated the state’s prohibition against using state funds for religious purposes and the state’s own statutes allowing local district control over curriculum.

As of now, until the court issues a final ruling, its decision marks a victory in Americans United’s attempt to stop Walters, said Alex Luchenitser, the organization’s associate legal director: “It protects the separation of church and state. It protects the religious freedom of students.” Speaking about the court’s stay, Walters, through spokeswoman Grace Kim, said in a statement: “The Bible has been a cornerstone of our nation’s history and education for generations. We will continue fighting to ensure students have access to this foundational text in the classroom.”

Meanwhile, Walters was also sued separately last summer by a parent in Locust Grove who contended the mandate violated the state and federal constitutions. The state education department has denied the claims of both suits and contended in legal briefs that using the Bible for its secular value does not violate the state’s constitution.

Walters’s mandate has also sparked concern because of the proposed social studies standards that followed. The standards, which were initially released in December and would require legislative approval, mention the Bible and its historical impact more than 40 times. Several of the standards attempt to erroneously frame the Bible, and specifically the Ten Commandments, as the foundation of American law. Biblical scholars from the University of Oklahoma and elsewhere believe these standards promote the long-standing trope of Christian nationalism, which is premised in part on the false idea that the nation’s founding documents stemmed from the Bible. (The founders were Bible readers, but not necessarily fans of the same versions or holy texts in general. In fact, Thomas Jefferson cut up pages of the Bible to remove mention of miracles or the supernatural.)

For example, Walters’s standards would require students in first grade to learn about David and Goliath, as well as Moses and the Ten Commandments, because the standards cite them as influences on the American colonists and others. Second graders would be asked to “identify stories from Christianity that influenced the American colonists, Founders, and culture, including the teachings of Jesus the Nazareth (e.g. the ‘Golden Rule,’ the Sermon on the Mount).”

Related: Inside the Christian legal campaign to return prayer to public schools

“These new standards,” said a news release from the state department of education, “reflect what the people of Oklahoma — and all across America — have long been demanding of their public schools: a return to education curricula that upholds pro-family, pro-American values.” (Walters’s press office, despite repeated requests, did not make the state superintendent available for an interview.)

Critics in Oklahoma and elsewhere see Walters’s Bible mandate as part of a broader Christian nationalist movement. “I think Oklahoma is the test case for the nation,” said Dawn Brockman, a Norman school board member.

Walters, though, has been steadfast in his belief that the mandate is legal and critical for the education of Oklahomans. In the fall, after Americans United sued, Walters wrote on X: “The simple fact is that understanding how the Bible has impacted our nation, in its proper historical and literary context, was the norm in America until the 1960s and its removal has coincided with a precipitous decline in American schools.”

But nothing is simple about the history of the Bible in America’s schools. When public schools started to open in the 1800s, some required regular Bible readings. From the beginning, that practice was controversial: Schools typically favored the King James Version, pitting Protestants against Catholics, and riots over school Bible readings broke out from the 1840s into the 1870s, said Mark Chancey, a professor of religious studies at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. By 1930, 36 states allowed Bible reading to be a requirement or an option, but another dozen banned such activities.

A few decades later, a Pennsylvania family sued their school district for heeding the state’s 1949 law requiring the reading of 10 Bible verses and the recitation of prayers at the start of each school day. In 1963, just a year after a similar opinion, the Supreme Court ruled that requiring in-school Bible readings and prayers was unconstitutional. After those rulings, daily teaching from the Bible, for the most part, was halted, Chancey said, but backlash continued, with critics charging that removing prayer and Bible readings from schools had led to a decline in the morality of schoolchildren.

Related: Teachers struggle to teach the Holocaust without running afoul of new ‘divisive concepts’ laws

In subsequent decades, the Supreme Court ruled against clergy-led prayer and prayer over the loudspeakers at football games in several school-related cases. But in a seeming reversal, in 2022, the high court ruled in favor of allowing a football coach to conduct midfield, postgame prayers, shifting the legal landscape. The majority’s opinion on the football coach’s prayer has prompted politicians and states to further test the limits of the separation of church and state. In February, lawmakers in Idaho and Texas even proposed measures to allow daily Bible readings in public schools again.

In Norman, many teachers reacted to news of the Bible mandate with concern and fear. Spanish teacher Darcy Pippins, who is in her 27th year at Norman High, said she sometimes teaches about Catholicism because it is the religion of the Spanish-speaking world. But putting a Bible in every classroom and teaching from it is different. “I just don’t feel comfortable,” said Pippins, also a parent. “I’m not qualified to teach and to incorporate the Bible into what I teach.’’

Other teachers, said Brockman, the school board member, worried about professional repercussions were they not to follow the mandate, given that Walters had already targeted at least one Norman teacher in the past for objecting to bans on particular books.

Nick Migliorino, the public school system’s superintendent since 2017, was the first superintendent in the state to publicly oppose the Bible mandate. When asked about it in a July interview with a local paper, he responded: “I’m just going to cut to the chase on that. Norman Public Schools is not going to have Bibles in our classrooms, and we are not going to require our teachers to teach from the Bible.”

Other superintendents followed, and by late July, at least 17 school district leaders said they had no plans to change curriculum in response to the Bible mandate, according to a report by StateImpact Oklahoma.

In an interview at his district’s headquarters, Migliorino emphasized that his school system already teaches how different religions affect history. Bibles, he noted, are accessible to students through the library. Migliorino added that the state superintendent had no authority to make school districts follow the mandate and that it would result in pushing Christianity on students.

“It’s a captive audience, and that is not our role to push things onto kids,” he said. “Our role is to educate them and to create thinkers.”

Oklahoma already has a 2010 measure allowing school districts to offer elective Bible classes and to give students the latitude to pick the biblical text they prefer to use. But unlike Walters’s mandate, it allows for different biblical perspectives, said Alan Levenson, chair of Judaic history at the University of Oklahoma and a biblical scholar. Even still, there has never been widespread interest in a Bible elective in Norman, said Jane Purcell, the school system’s social studies coordinator. Nor was there much interest in such a class when she taught in Florida. Since 2006, at least a dozen states have passed laws promoting elective Bible classes.

This may be, in part, because educators worry about potential issues with teaching Bible courses, said Purcell: “It’s very easy for it to appear to be proselytizing.”

Related: How one district has diversified its advanced math classes — without the controversy

Walters, for his part, has not taken any of this pushback in stride. At a July 31 state board of education meeting, he lashed out against “rogue administrators” who opposed him, saying of the left: “They might be offended by it, but they cannot rewrite our history and lie to our kids.”

After the public schools superintendent publicly rejected Walters’s mandate, community members and teachers in Norman expressed relief. Meg Moulton, a realtor and mother of three, came to a July board meeting to thank the superintendent in person. “I’m a Christian mama,” she said. “I love teaching my kids about God. I love going to church.”

But, she added, “Ryan Walters’s mandate makes it so that teachers and students who may not be Christians…[or] who may believe something different, are going to be essentially forced to learn something that they may not believe in.”

Students and others I met with at a popular Norman coffee shop said they were concerned about how Walters’s mandate could affect religious minorities, women, and members of the LGBTQ+ community. “What Ryan Walters is trying to push goes in line with a lot of trends of kind of pushing back against LGBTQ,” said Isandro Moreno, a 17-year-old senior at Norman High.

Phoebe Risch, a 17-year-old senior at Norman North, the town’s other public high school, said Walters’s mandate was part of what motivated her to restart her high school’s Young Democrats club and recruit roughly 30 members. Risch, already upset about her state’s readiness to ban abortion following the Supreme Court’s overturn of Roe v. Wade, fears that requiring Bible-based instruction could lead to the promotion of the idea that women are submissive. “As a young woman, the implications of implementing religion into our schools is a little scary,” she said, “especially because Oklahoma is already a very conservative state.”

Among the half dozen teens attending a confirmation class in December at Oklahoma City Reform temple B’nai Israel, most opposed the mandate, except for one. She said she supported it as long as the classroom teacher was careful and encouraged critical thinking.

One teen recounted tearily how, during class the previous week, a friend had drawn a swastika on her paper as a taunt. “Stuff like that is so normalized,” she said. “It’s antisemitism. If that’s so normalized, normalizing Christianity further, it’s just worse.”

Imad Enchassi, an imam who oversees an Oklahoma City mosque and serves as chair of Islamic studies at Oklahoma City University, echoed similar fears for the Muslim community. “We’re already experiencing Islamophobia. Muslim kids who wear the headscarf already have been told they’re going to hell because they don’t believe in the Bible or they don’t believe in Jesus,” he said. “When curriculum mandates one religion over the other, that will further isolate our children.”

Some Oklahomans, though, do support the mandate. And at one of the state board of education meetings where Walters touted it, three residents expressed support for the idea — during public comment — as did at least one board member. That board member said he thought biblical literacy was important, while other supporters see the Bible mandate as a way to instill morality in the public schools. Ann Jayne, a 62-year-old resident of Edmond, about 15 miles north of Oklahoma City, makes a point of letting Walters know on his Facebook page that she’s praying for him, because she believes public schools need to instill Christian values. “I think we need church in the state,” she said. “I don’t see a problem with God being back in the school. Nobody is forcing them to become a Christian.”

Since last summer, Walters’s efforts to push Christianity have only become bolder. In mid-November, he announced the opening of the Office of Religious Liberty and Patriotism, which would, among other things, investigate alleged abuses against religious freedom and patriotic displays. Two days later, he announced that he was sending 500 Bibles to Advanced Placement government classes. He also emailed superintendents around the state with the order to show their students a one-minute-and-24-second video announcing the religious liberty office and praying for newly elected President Trump.

At a Christmas parade in Norman in early December, some residents called the video embarrassing, with many superintendents, including Norman’s, having declined to show it. However, while many residents seem to abhor the Bible mandate, they do not agree on how religion should be handled in public life. Despite some religious diversity and some liberal leanings common in a university town, Norman skews religiously conservative. That dichotomy means many residents see the Bible as so sacrosanct that they don’t want it taught in schools, yet they see no problem with other Christian-oriented school activities.

In some cases, residents like school board member Brockman, who is also a former teacher and lawyer with training on the First Amendment, have objected to school promotion of the religious aspects of Christmas. When she was a teacher at one of Norman’s two high schools, she asked to stop the playing of overtly religious Christmas songs in the halls during passing periods. She saw it as a “gentle reminder that the Supreme Court says we need to remain neutral on religion.” Her wish was granted. “They took it down with some consternation and played the Grinch in my honor.”

Related: Teaching global warming in a charged political climate

Residents have also quibbled over what to call the parade featuring Santa each December. Should it be called the Norman holiday or Christmas parade? It’s now known as the Norman Christmas Holiday Parade. In early December, the city’s mix of liberal and conservative influences shone through the glitz during the parade. The Knights of Columbus float had a sign that said “Merry CHRISTmas.” Norman’s Pride organization participated, with its human angels wearing wings lit up in rainbow colors.

Tracey Langford, watching the parade from the back of her SUV, was dressed in a red stocking cap and a red sweatshirt that read “Santa, define good,” a jab at the fact that she is a lawyer who cares about legal definitions. To her, the Bible mandate is a clear violation of separation of church and state.“Every home here has a Bible…. We don’t need to spend a dollar to get a Bible in every classroom,” said Langford, a lawyer at the University of Oklahoma and a parent of a first grader in Norman schools and a 15-year-old in a private school.

Traci Jones, a parent of both a Norman sixth grader and fifth grader, likewise asked, “Who’s supposed to be teaching these kids the Bible? Is it just a random person? What if it’s an atheist or someone who has totally different beliefs than me?” As a nondenominational Christian, she added, “I think it’s wack to ask these poor teachers to teach that.”

What happens next may ultimately be decided in a courtroom. There is no sign yet when final opinions may be issued in either lawsuit.

State lawmakers at recent appropriation hearings said they were worried about the directive’s constitutionality, and in fact, in March, the Senate Appropriations’ Education Subcommittee said it did not consider Walters’s $3 million request to purchase Bibles. The next day Walters announced he was launching a national campaign with a country singer to get Bibles donated to Oklahoma schools. (The legislature gets the final word on the Bible purchases, a line item in the education budget, and the standards, which the state board of education approved in late February.) Meanwhile, the fate of religion’s place in public schools on a national level likely will rest with the Supreme Court, with various lawsuits against state measures promoting Christianity making their way through the court system.

In Norman, Jakob Topper, Kyle Tubbs and other Baptist pastors I met with at the headquarters of a statewide Baptist church organization were increasingly aghast at Walters’s mixing of religion and politics. Rick Anthony, pastor of Grace Fellowship, a Baptist church, centered his November 17 sermon on such concerns. “Almost comically, we’ve heard this week about a video made that was ordered to be shown to all children in the public schools and then sent to their parents,” he said. “Our question is…where are our voices as our political leaders cozy up to faith leaders, all the while destroying our faith institutions?”

Kaily Tubbs, Tubbs’s wife and a fifth grade teacher in Norman schools, said the mandate conflicts with her personal belief on how faith should be handled in schools. She spoke also as a mother of a kindergartener and a third grader, both in Norman schools. “Our faith is really important to us,” she said. “I don’t want it to be used as a prop in a classroom.”

Topper said that at his church, the majority of his congregation believes in separation of church and state. He said he is aware of the religious diversity that exists in his town, too, and has both Muslim and Jewish neighbors. Like Anthony, he spoke with his congregation about Walters’s mandate, though in an informal weeknight meeting at his church, rather than as part of a formal sermon. “I wish,” he said, “that Jesus was left out of schools and left for the religious realm.”

Contact editor Caroline Preston at 212-870-8965, via Signal at CarolineP.83 or on email at [email protected].

This story about Bibles in schools was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.

Logistics & Supply Chain and the Garatoni School of Entrepreneurship and Innovation at Ivy Tech Community College. With a lifelong passion for

Logistics & Supply Chain and the Garatoni School of Entrepreneurship and Innovation at Ivy Tech Community College. With a lifelong passion for  Samantha Candler is a General Motors World Class Technician with 18 years of experience in the

Samantha Candler is a General Motors World Class Technician with 18 years of experience in the  experienced educator. With a decade’s worth of experience teaching various

experienced educator. With a decade’s worth of experience teaching various  Monica Hampton is a retired cybersecurity officer, an Adjunct Professor of Cybersecurity and Criminal Justice and an Instructional Designer at Benedict College. Monica’s teaching experience stretches far beyond the higher ed classroom, having previously taught firearms and safety, as well as cybersecurity to law enforcement officers at national and local levels. She now brings personal field experience and real-world insights to her students, teaching undergraduate cybersecurity and

Monica Hampton is a retired cybersecurity officer, an Adjunct Professor of Cybersecurity and Criminal Justice and an Instructional Designer at Benedict College. Monica’s teaching experience stretches far beyond the higher ed classroom, having previously taught firearms and safety, as well as cybersecurity to law enforcement officers at national and local levels. She now brings personal field experience and real-world insights to her students, teaching undergraduate cybersecurity and  Community Health Department at Mercyhurst University. Her experience spans across undergraduate, graduate and study abroad programs, where she teaches multiple courses, both online and in-person. Some of those courses include Methods and Social Science Statistics. Holding a Ph.D. in criminology from Indiana University of Pennsylvania, EmmaLeigh’s focus has been primarily within the higher ed sphere. Yet, she’s also a leading example of how to enact meaningful community-based change outside the classroom. She currently serves on the executive board for the Northeastern Association of Criminal Justice Sciences and is the faculty advisor of the Criminal Justice Association. EmmaLeigh’s various outreach efforts and contributions represent her resolution to make a difference.

Community Health Department at Mercyhurst University. Her experience spans across undergraduate, graduate and study abroad programs, where she teaches multiple courses, both online and in-person. Some of those courses include Methods and Social Science Statistics. Holding a Ph.D. in criminology from Indiana University of Pennsylvania, EmmaLeigh’s focus has been primarily within the higher ed sphere. Yet, she’s also a leading example of how to enact meaningful community-based change outside the classroom. She currently serves on the executive board for the Northeastern Association of Criminal Justice Sciences and is the faculty advisor of the Criminal Justice Association. EmmaLeigh’s various outreach efforts and contributions represent her resolution to make a difference.