Editor’s note: This guest entry, also available on Inside Higher Ed, has been kindly contributed by Professor Dato’ Dr Morshidi Sirat. Morshidi was the former Director-General of Higher Education Malaysia, and is now Director of the Commonwealth Tertiary Education Facility (CTEF) based at Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang. Morshidi is also a Senior Research Fellow at the National Higher Education Research Institute (IPPTN), Universiti Sains Malaysia. Given Morshidi’s expertise and experience in higher education policy, he is often engaged in consultancy work on higher education policy in Malaysia, then Association of Southeast Asian Region (ASEAN) and the South Pacific Island States.

This entry is based on recent work in ASEAN and South Pacific Island States, specifically to address confusion between international education and the internationalisation of education in many emerging and developing higher education systems. In many systems, these terms are used interchangeably. This entry is an attempt to re-examine international education as a concept and a strategy for both international understanding and economic development as implemented in Malaysia. Arguably, lessons learnt should provide guidance for Malaysia’s international education beyond 2020, especially with respect to the manner in which Malaysia’s citizens “engage with others in this globalised and yet highly divisive world.” Kris Olds

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Malaysia’s International Education by 2020 and Beyond:

Re-examining Concept, Targets and Outcome

Morshidi Sirat

Preamble

It is important to address international education in this era of globalisation and unsettling geopolitical issues, in particular on Malaysia’s response to preparing Malaysians for future global and regional scenarios. Anyone that studies international development dynamics from the ‘people perspective’ as opposed to the ‘economic and neo-liberalism perspective’ will almost immediately agree that we are in dire need of international and intercultural understanding as we try to deal with longstanding and more importantly, emerging geopolitical issues. As such, international education is not merely about the dynamics of flows in terms of the numbers of students, scholars, and/or programs between countries. More importantly, it is about qualitative impact, in particular about the content of international education and related programs. It must be emphasized that “in any educational program, of any educational system, for any educational process and under any educational material”, the aims and objectives of international education must be communicated in order to realise international understanding among nations (Juan Ignacio Martínez de Morentin de Goñi, 2004: 94).

With this as a preamble and context, we can then proceed to re-examine international education as a concept and as a strategy for both international understanding and economic development as implemented in Malaysia.

Introduction

With globalisation, many terms connected with the “international” are loosely defined and liberally adopted in policy circles particularly in the formulation of strategic planning directions on education and higher education. These policy documents and the people behind these policy documents are equally guilty of adopting terms and terminologies without proper definition, contextualisation and correct usage of these terms. Thus, in our attempt to trace and assess the progress of international education in Malaysia to-date it is important at the outset to provide a working definition of ‘international education’. But more importantly, it is pertinent for us to establish whether, at the time of target setting for the so-called international education in 2007 (for the National Higher Education Strategic Plan Phase 1), the Economic Transformation Plan (ETP) and in 2013 (in the case of the Malaysia Education Blueprint), did we conceptualise and operationalise the term ‘international education’ as it should be conceptualised and operationalised? Moving on from issues and questions which I have raised earlier, this entry will begin with a deliberation on the term ‘international education’, detailing the aims and objectives of international education. Subsequently, a working definition is adopted in order to assess where Malaysia is in terms of international education. Following that, the ‘international education’ element in the Malaysia Education Blueprint and the National Higher Education Strategic Plan (NHESP) will be highlighted and the implementation of international education rated. A statement of “where we are” and “where we should be heading” will be offered for further consideration and deliberation based on the Malaysia Education Blueprint, 2015-2025 (Higher Education).

What is International Education?

Admittedly, the term ‘international education’ has yet to acquire a single, consistent meaning. The reason for the uncertainty, confusion and disagreement lies partly in the many interpretations of the term ‘international education’. As James (2005:314) notes, further confusion arises because the word ‘international’ itself is equally ambiguous as not all things regarded as international are in essence international. To understand the meaning of international education, we need to explicate the term in terms of aims and objectives.

Epstein (1994: 918) describes ‘international education’ as fostering “an international orientation in knowledge and attitudes and, among other initiatives, brings together students, teachers, and scholars from different nations to learn about and from each other. In other words, “All educative efforts that aim at fostering an international orientation in knowledge and attitudes” (Huse´n and Postlethwaite, 1985: 260) and seek “to build bridges between countries” (McKenzie, 1998: 244) fit this idea of international education. Arum (1987) divides international education into three parts: (1) international studies (including all studies involving the teaching or research of foreign areas and their languages); (2) international educational exchange (involving American students and faculty studying, teaching, and doing research abroad and foreign faculty and students studying, teaching, and doing research in the United States); and (3) technical assistance (involving American faculty and staff working to develop institutions and human resources abroad, primarily in Third World countries).

The justification for international education can be approached from two directions: a ‘top-down’ approach considers addressing global and national needs, and a ‘bottom-up’ approach, that is the development of the individual. These approaches are not mutually exclusive (James, 2005: 315). Thomas (1996: 24), writing on the development of an International Education System, asserts that ‘education is uniquely placed to provide lasting solutions to the major problems facing world society’, problems which transcend political borders (Gellar, 1996).

The Mission and Aims of International Education

Belle-Isle (1986) states that the “mission of international education is to respond to the intellectual and emotional needs of the children of the world, bearing in mind the intellectual and cultural mobility not only of the individual but . . . most of all, of thought”.

The aims of international education are related to developing ‘international understanding’ for ‘global citizenship’, and the knowledge, attitudes and skills of ‘international-mindedness’ and ‘world-mindedness’ (Hayden and Thompson, 1995a, 1995b; Schwindt, 2003; YAIDA, 2007). Admittedly, none of the aims of modern ‘international education’ are exclusively international (James, 2005: 324). Therefore, and in a post-9/11 world, the term ‘internationalist’ may no longer be sufficient to describe the values espoused by the movement; it might be time to transcend ideas based on nation-states (Sarup, 1996; in Gunesch, 2004). Gunesch (2004) proposes ‘cosmopolitanism’ as an alternative name for the outcome intended of ‘international education’ (Mattern, 1991). While the aims of international education are laudable, it is misleading to relate them to internationalism, for they extend beyond differences in nationality (James, 2005: 323). Peterson (1987) asserts that international education seeks instead to produce what might be termed ‘cosmopolitan locals’, who have a national identity, understand others better, seek to co-operate and have friends across frontiers. That cosmopolitan is “familiar with many different countries and cultures” and “free from national prejudices”. OED (2004) indicates the potential limitations of the cosmopolitanism, in associating prejudices with nations. But, it is preferable as a term to ‘international’ in the sense that it does transcend purely nation-based associations.

Towards a Working Definition

Any working definition for international education should appropriately address the issue of “global interconnectedness that characterizes the contemporary world, and point to a form of international understanding required by the citizen of the future that must comprise some understanding of the world perceived as a whole.”

UNESCO experts have developed conceptual approaches to international education that resulted in an operational definition being adopted by UNESCO (1974). I must emphasize here that we are more interested in a working definition and not an academic definition. UNESCO’s effort may be considered as the only large-scale effort to provide a working definition of the term “international education” by a widely recognized international educational body. The definition, agreed at UNESCO General Conference level, combined the elements of international understanding, cooperation and peace with the range of focal points of international education under the overall rubric of “education for international understanding”. UNESCO (1974: 2) outlines the following relevant educational objectives for international education:

- a curriculum with a global perspective

- understanding and respect for other peoples and cultures

- human rights and obligations

- communication skills

- awareness of human interdependence

- necessity for international solidarity

- engagement by the individual in the local, national and global scale

Malaysia’s International Education

At this juncture, let us pose some pertinent questions: To what extent is international education important in the educational process and the education system in Malaysia? Personally, I like to think it should be important as “There is nothing that is more effective than having nations-states and people break down barriers between themselves.” In fact, in this highly globalised and inter-connected world it is imperative that we understand other cultures, languages, institutions, and traditions. More so, in today’s globalized world, Malaysian students and in fact students of ASEAN need more international experience. For Malaysia, foreign students enrich our campuses and our culture, and they return home with new ideas and ways to strengthen the relationship between countries. But interestingly, since the early 1990s, the market place and international education have become intertwined and international education has and continues to be seen as an engine for growth (see http://www.nxtbook.com/naylor/IIEB/IIEB0114/index.php – /38). Let us not mention the contribution of international students to the Malaysia economy at this juncture as I want to focus on aspects or issues that are beyond the monetary in this entry. That is, I want to focus on to what extent Malaysia has been successful in leveraging international education as a vital part of 21st century diplomacy. Admittedly, we send undergraduates, graduate students, administrators, faculty, and researchers on short and long-term programs abroad but what is more important and pertinent question to ask is: what are the impacts of our programs on students and scholars from abroad in Malaysian education system? Another question that beg some answers: Malaysia education institutions are implementing internationalisation-related activities such as international student mobility, but are these institutions themselves internationalised in its leadership, governance and management arrangement, curriculum content and pedagogy?

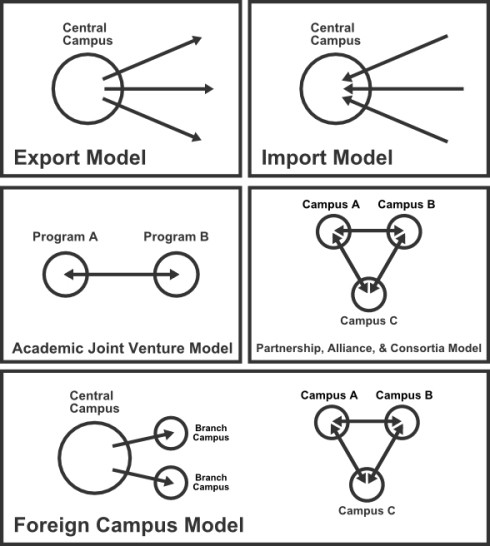

The National Higher Education Strategic Plan, 2020 (NHESP), while adopting UNESCO’s operational definition for international education, could not be regarded as intending to progress the comprehensive aims and objectives of international education. This strategic planning document addresses the internationalisation of higher education and not international education. The NHESP fleetingly touched on the aims and objectives of international education by way of the benefits of international exposure and experience. For instance, while a “curriculum with a global perspective” is embedded in many courses offered by Malaysian universities, this is targeted at international student enrolment and recruitment or providing exposure to local students with limited global citizenship or international understanding objective. At best, these are offered at the “exposure level”. Promoting the establishment of Malaysian branches of foreign universities in Malaysia is widely regarded by policy makers as one element of international education. However, the introduction of the Malaysia’s Global Reach component in phase two of the implementation of the NHESP, 2011-2015 is an attempt to insert amendment to what is incomplete from the perspective of international education. Malaysia’s Global Reach was introduced with international education for 21st century diplomacy in mind.

If we examined international education from more recent government documents, in particular the recently launched Malaysia Education Blueprint, 2013-2025, it is stated that:

“…it is …imperative that Malaysia compares its education system

against international benchmarks. This is to ensure that

Malaysia is keeping pace with international educational

development.” (Ministry of Education, 2013: 3-5).

Our reading of this important document is that the emphasis is on “international educational development” and not “development in international education.” The international education element of the Blueprint is the International Baccalaureate (IB) programme, which is designed to develop inquiring, knowledgeable and caring young people who help to create a better and more peaceful world through intercultural understanding and respect (international education), are offered only in two Fully Residential Schools in Malaysia) (Ministry of Education, 2013:4-6).

At another level, the International Schools, which use international curriculum such as the British, American, Australian, Canadian, or International Baccalaureate programmes, sourced their teachers from abroad. In terms of enrolment, data as of 30 June 2011 shows that 18% of Malaysian students in private education options are enrolled in international schools nationwide (Ministry of Education, 2013:7-11).

With a very restricted notion or definition of international education, based on the NHESP and re-emphasized in the Malaysia Education Blueprint, 2013-2025, the Performance Management Delivery Unit, and Prime Minister’s Department (PEMANDU) subsequently identified prioritised segments of the education system to drive the economic growth of the nation, namely:

- Basic Education (primary and secondary), with Entry Point Project (EPP) identifying the private sector as playing an important role in improving basic education in terms of the provision of international education, as well as in the training and upskilling of teachers.

- Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET), with EPP 12: Championing Malaysia’s International Education Brand aims to position Malaysia as a regional hub of choice in the global education network. This will include marketing vocational training to international students. This EPP’s goal is to transform a foreign student’s experience in Malaysia into one that is comparable to that in Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States. Thus, targets are set as Gross National Income (GNI) by 2020 (mil) RM2, 787.7 and 152,672 -projected jobs by 2020.

The prioritised segments identified above complement the regional education hub, which is the thrust for the NHESP. For the Malaysia Education Blueprint, 2015-2025 (Higher Education), the notion of international education was not conceptualised in the context of achieving UNESCO’s aims and objectives of international education as opposed to internationalisation of higher education and its monetary aspect to the Malaysian economy. In this Blueprint, the shifts on “Holistic, Entrepreneurial and Balanced Graduates’ and ‘Global prominence’ are conceived primarily in terms of monetary return and institutional reputation. There is no direct and clear statement in the Malaysia Education Blueprint, 2015-2025 (Higher Education), with respect to UNESCO (1974) guidelines on international education and the outcome for the students in a highly interconnected but at the same time highly divisive world. What can we improve upon in the next 15 years, is to present the idea of international education beyond the notion that international education is about “engine of growth for the national economy”. Arguably, we need to re-orientate our efforts towards international understanding, citizenship and (mutual rather than soft power) diplomacy (Knight, 2014).

Conclusion

The term international education has yet to acquire a single, consistent meaning. But the manner in which Malaysia interprets and uses this concept/term in the context of economic development need some reflection and re-examination. We may achieve the targets set for 2020 in terms of international student enrolment in our education system, but what about the real aims and objectives of international education, which is to realise international understanding among nations. We need to seriously examine whether the aims and objectives of international education are effectively embedded in Malaysia’s (i) educational program, (ii) educational system, (ii) educational process and (iv) educational material.” There is a need to reassess Malaysia’s commitment towards creating the goals of international mindedness and ‘international understanding’ beyond 2020 and in the context of the Transformasi Nasional 2050 or National Transformation 2050 (TN50). In the case of Malaysia, where economic development is of top priority, we need to seriously think in terms of the economic impetus for better intercultural understanding. Nothing much could move forward in the Malaysian context unless and until there are clear economic impetus for any initiatives coming out of the higher education institutions. We need to re-look at this economic premise if we are to emerge as a nation of ‘global prominence” with respect to the manner our citizen engage with others in this globalised and yet highly divisive world.

References

ARUM, S. ‘International Education: What Is It? A Taxonomy of International Education of U.S. Universities.’ CIEE Occasional Papers on International Educational Exchange, 1987, 23, 5–22.

BELLE-ISLE, R. (1986) ‘Learning for a new humanism’. International Schools Journal 11 Springs: 27–30.

EPSTEIN, E.H. (1994). Comparative and International Education: Overview and Historical Development. In: Torsten Husén and T. Neville Postlethwaite, eds., International Encyclopaedia of Education (p.918–923). Oxford: Pergamon Press.

GELLAR, C.A. (1996) ‘Educating for world citizenship’ International Schools Journal 16(1): 5–7.

GUNESCH, K. (2004) ‘Education for cosmopolitism? Cosmopolitanism as a personal cultural identity model for and within international education’. Journal of Research in International Education 3: 251–75.

HAYDEN, M.C. AND THOMP SON, J. J. (1995a) ‘International Education: The crossing of frontiers’. International Schools Journal 15(1): 13–20.

HAYDEN, M.C. AND THOMP SON, J. J. (1995b) ‘International Schools and International Education: A relationship reviewed’. Oxford Review of Education 21(3): 327–45

HUSE´ N, T. AND POSTLETHWAITE , T.N. (1985) The International Encyclopaedia of Education. Oxford: Pergamon.

JAMES, KIERAN. (2005). ‘International education: The concept, and its relationship to intercultural education Journal of Research in International Education’, December 2005; vol. 4, 3: pp. 313-332. Available at: http://jri.sagepub.com/content/4/3/313.full.pdf+html

JUAN IGNACIO MARTÍNEZ DE MORENTIN DE GOÑI. (2004). What is International Education? UNESCO Answers. San Sebastian: UNESCO Centre. Available at: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0013/001385/138578e.pdf

KNIGHT, JANE. (2014). ‘The limits of soft power in higher education’. University World News, 31 January 2014 Issue No:305.

MINISTRY OF EDUCATION (2013.) Malaysia Education Blueprint, 2013-2025. Putrajaya: Ministry of Education.

OED (2004). The Concise Oxford English Dictionary, 11th edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

PETERSON, A.D.C. (1987). Schools across Frontiers: the Story of the International Baccalaureate and the United World Colleges. Chicago, IL: Open Court.

MATTERN, W.G. (1991). ‘Random ruminations on the curriculum of the international school’, in P.L. Jonietz and D. Harris (eds) World Yearbook of Education 1991: International Schools and International Education, pp. 209–16. London: Kogan Page.

McKENZI E , M. (1998). ‘Going, going, gone . . . global!’, in M.C. Hayden and J.J. Thompson (eds) International Education: Principles and Practice, pp. 242–52. London: Kogan Page.

SARUP, M. (1996). Identity, Culture and the Postmodern World. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

SCHWINDT, E . (2003). ‘The development of a model for international education with special reference to the role of host country nationals’. Journal of Research in International Education 2(1): 67–81.

THOMAS , P. (1998). ‘Education for peace: The cornerstone of international education’, in M.C. Hayden and J.J. Thompson (eds) International Education: Principles and Practice, pp. 103–18. London: Kogan Page.

UNESCO (1974). Recommendations Concerning Education for International Understanding, Co-operation and Peace and Education Relating to Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms: adopted by the General Conference at its eighteenth session in Paris, November, 1974. UNESCO, Paris.

YAIDA PUSUSILTHORN (2007). International Mindedness among Expatriate Teachers in Bangkok Patana School. MA Thesis. Language Institute, Thammasat University, Bangkok. Feb. available at: http://digi.library.tu.ac.th/thesis/lg/0262/01TITLE.pdf

Marcus Lingenfelter, Edmentum’s newly-appointed Senior Vice President of Strategic Initiatives and Partnerships, has two decades of leadership experience in postsecondary education including campus roles at the University of Virginia and Penn State University along with cabinet-level positions at Widener University and Harrisburg University of Science and Technology. He previously served as Senior Vice President of Advancement for the National Math and Science Initiative (NMSI) – the non-profit established to dramatically improve math and science educational outcomes for the country.

Marcus Lingenfelter, Edmentum’s newly-appointed Senior Vice President of Strategic Initiatives and Partnerships, has two decades of leadership experience in postsecondary education including campus roles at the University of Virginia and Penn State University along with cabinet-level positions at Widener University and Harrisburg University of Science and Technology. He previously served as Senior Vice President of Advancement for the National Math and Science Initiative (NMSI) – the non-profit established to dramatically improve math and science educational outcomes for the country.

Jason Scherschligt joins Edmentum as Vice President of Product Strategy and Experience. He brings more than 18 years of experience leading innovative product management and user experience approaches in organizations like the Star Tribune, Capella University, Jostens and GoKart Labs. Jason will focus on designing and managing industry changing, captivating education products that truly empower educators, engage students, and provide education leadership with the insights they need to develop and maintain education programs that create access, equity, engagement, and positive learning outcomes.

Jason Scherschligt joins Edmentum as Vice President of Product Strategy and Experience. He brings more than 18 years of experience leading innovative product management and user experience approaches in organizations like the Star Tribune, Capella University, Jostens and GoKart Labs. Jason will focus on designing and managing industry changing, captivating education products that truly empower educators, engage students, and provide education leadership with the insights they need to develop and maintain education programs that create access, equity, engagement, and positive learning outcomes. Christy Spivey assumes the role of Vice President of Curriculum and Assessment Development for Edmentum. During her tenure, Christy has served in a variety of roles shaping the company’s curriculum development strategy. Embracing her experience in the classroom, she ensures educators are involved in every step of Edmentum’s design and development to provide programs that meet the needs of educators everywhere. Christy leads a team of deeply committed curriculum and assessment designers focused on creating a new paradigm in differentiated instruction, blended learning, and active learning models.

Christy Spivey assumes the role of Vice President of Curriculum and Assessment Development for Edmentum. During her tenure, Christy has served in a variety of roles shaping the company’s curriculum development strategy. Embracing her experience in the classroom, she ensures educators are involved in every step of Edmentum’s design and development to provide programs that meet the needs of educators everywhere. Christy leads a team of deeply committed curriculum and assessment designers focused on creating a new paradigm in differentiated instruction, blended learning, and active learning models.

Spotted this earlier today on LinkedIn. We don’t have anyone from scientific publishing coming to speak at our PhD Horizons Careers Conference on 6th June (www.bit.ly/phdhorizons) so check out the webinar below if you think it may be an interesting career for you.

PhDs & Postdocs – learn more about editorial and publishing roles Nature Research (Publishing). Webinar 30th May. Register here: go.nature.com/2rhTZmO