There’s no denying climate change when a tornado rips through your town or a blizzard buries you in snow. So why blame the people who raise weather alarms?

Source link

Category: global warming

-

Decoder Replay: Can we prepare for unpredictable weather?

-

Are you aware of your level of climate ignorance?

Do you know which country emits the most greenhouse gases per capita? If not, you aren’t alone.

I’m a student at The Climate Academy, an international organization founded by philosopher and climate activist Matthew Pye who teaches students about climate change from a systems point of view.

This year, we surveyed almost 500 people in Brussels, Varese and Milan to analyse the level of climate literacy among populations across Europe. Many people we surveyed pointed at large emitters such as the United States, China and India.

Yes, these are big emitters in quantity, but when it comes to per capita emissions — the amount divided by the population of the country — the top three are smaller, wealthy countries: Singapore, the United Arab Emirates and Belgium.

These numbers can be explained by the extremely consumeristic, luxury lifestyle of the overwhelming majority of their citizens and the over-reliance on fossil fuels for generating energy. Yet, in our survey, 378 people out of 468 — 81% — named the United States, China or India.

We must refocus the lens.

What does this mean? That the media attention is on the wrong players. As stated by the World Economic Forum:

“When India surpassed the European Union in total annual greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in 2019 becoming the third largest emitting country after China and the United States, that statistic only told part of the story. India’s population is nearly three times larger than that of the EU, so based on emissions per person, India ranks much lower among the world’s national emitters.”

It is crucial to look at per capita emissions. That’s the conclusion of the Global Change Data Lab, a nonprofit organization that produces Our World in Data. It argues that annual national emissions do not take population size into account.

“All else being equal, we might expect that a country with more people would have higher emissions,” it reported. “Emissions per person are often seen as a fairer way of comparing. Historically — and as is still true in low- and middle-income countries today — CO2 emissions and incomes have been tightly coupled. That means that low per capita emissions have been an indicator of low incomes and high poverty levels.”

Europe often points at big emitters, but the comfortable lifestyles Europeans have due to their higher living standards aren’t sustainable.

Who to blame for climate change?

There’s a misconception that the more a country emits, the more responsible the country is for climate change.

This is the result of intense lobbying and voluntary misdirection by the richest. The wealthiest individuals are undoubtedly responsible for a considerably higher share of global emissions. But we’re often told that countries like China and India are the most responsible, as they are some of the world’s biggest polluters, a fact which is widely recognized.

Pye said it isn’t a surprise that the focus is on numbers at the macro level, as international organizations like the United Nations were created by the main global powers and they are still funded mainly by them.

“Keeping the language and the numbers about the problem general and global masks the fact that the majority of our [per capita] emissions are still from these rich nations,” he said. “This lack of clarity about who is responsible is reflected right across global media coverage. It is not by chance that we don’t have a clear view of the vital statistics, it is by subtle and powerful design.”

The UN is founded on the principle of human rights, he said.

“Should it not think and act on climate change with everyone having an equal right to the air?” Pye said. “When you look at per capita and consumption emissions the whole landscape of responsibility is radically different.”

Surveying people about greenhouse gases

I conducted my part of the survey in a middle-class neighborhood of Brussels.

When I asked a 20-year-old, “What would the consequences of a two degree increase in global temperature be?” I got this answer: “More meteorites.” When I put the same question to someone 50 years of age, the answer was, “It’s going to be cold.”

A 75-year old told me: “I don’t believe in climate change. There were examples of extreme heat in the 17th century, it is natural. Climate change is a tool of the government to control us.”

All of these are misconceptions about weather events, temperature patterns and the source and type of climate change we experience.

Now, this survey included only a small sample of the population. But it already shows that the misconceptions in education about climate change are real and existent across every generation and in many ways. Many other surveys made by reputable organizations have supported this conclusion.

What people don’t know

A 2010 report by the Yale University Program on Climate Change Education found that 63% of Americans believed that global warming was happening, but many did not understand why. In this assessment, only 8% of Americans had knowledge equivalent to an A or B, 40% would receive a C or D, and 52% would get an F.

A report by King’s College in London, based on a 2019 survey, found a similar level of ignorance.

Misconceptions are still here, waiting to be tackled. It starts in schools, where new, fresh generations without bias or misconceptions are formed. It starts at home, where parents should adapt and teach their kids the basics. Proper educational programs should be set up by governments.

This seems natural. But just a few months ago, in the United States, the Trump administration cut funding for schools that hold educational programs on climate change and greenhouse gas emissions reduction.

Educational systems, too, spread misconceptions about climate change. Because we never stop learning, educational systems shouldn’t have such flaws and should provide accurate information.

As we dive deeper into the climate crisis, proper knowledge and understanding will be key to systemic change and governmental response.

Until information on climate change becomes a public good, we will continue to “debate what kind of swimming costume we will wear as the tsunami comes.” Those are the words of then-U.S. Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson before the 2008 financial crisis.

Questions to consider:

1. Why is it important to consider the size of a population when considering responsibility for climate change?

2. What is meant by “climate ignorance”?

3. How can you learn more about climate change?

-

Why so much confusion over climate change?

Bwambale estimates that less than 1% of the global population truly grasps the implications of climate change. “Even worse are Ugandans,” he said.

Gerison pointed out that much of the population of Uganda is young. “With 80% below the age of 25, many haven’t witnessed the full extent of climate changes,” he said.

A diminishing crop is easily understood.

Janet Ndagire, Bwambale’s colleague, said it is difficult for Ugandan natives to connect with climate campaigns. They often perceive them as obstacles to survival rather than crucial interventions.

“Imagine telling someone who relies on charcoal burning for survival that cutting down a tree could be hazardous!” Ndagire said. “It doesn’t make sense to them, especially when the tree is on their plot of land.”

Reflecting on personal experiences, Ndagire recalled childhood days of going to sleep fully covered. Nowadays it is too hot to do that, he said.

Ssiragaba Edison Tubonyintwari, a seasoned bus driver originally from western Uganda but currently driving with the United Nations, recounts the challenges of driving between 5 and 9 AM in the Albertine rift eco-region especially around the Ecuya forest reserve.

“It would be covered in mist,” said Tubonyintwari. “We’d ask two people to stand in front, one on either side of the bus, signalling for you to drive forward, or else, you couldn’t see two metres away. Currently, people drive all day and night!”

Irish potatoes in the African wetlands

What happened? Tubonyintwari pointed to unauthorised tree cutting in the reserve, residential constructions and the cultivation of tea alongside Irish potatoes in the wetlands. The result was rising temperatures.

His account supplements a Global Forest Watch report which puts commodity-driven deforestation above urbanisation.

It’s notable that Tubonyintwari didn’t explicitly use the term “climate change,” yet the sexagenarian can effectively explain the underlying concept through his detailed description of altered environmental conditions.

Global Forest Watch reports alarming deforestation trends, with 5.8 million hectares lost globally in 2022. In Uganda, more than 6,000 deforestation alerts were recorded between 22 and 29 November this year.

The consequences of such environmental degradation are dire. Ndagire emphasised that those who once wielded axes and chainsaws for firewood are now the very individuals facing reduced crop yields due to extreme weather conditions.

Even as Uganda grapples with the aftermath of a sudden surge in heavy rains from last October, Bwambale questions the country’s meteorological department, highlighting the failure to provide precise explanations and climate-aware preparations.

These interconnected narratives emphasise the need for accessible climate campaigns and community-driven solutions. As COP28 gathers elites, the call for a simplified narrative gains prominence, mirroring successful communication models seen during the Covid-19 pandemic; else it’s the same old throwing of good money after bad.

Questions to consider:

1. Why does deforestation continue in places like Uganda when people know about its long-term consequences?

2. In what ways are high level discussions about climate change disconnected from people’s everyday experiences?

3. In what way do you think scientists and environmentalists need to change the climate change narrative?

-

When a company’s enviro claims sound convincing …

Many companies contribute to the climate crisis and make a profit doing so. As consumers and governments pressure them to reduce their carbon emissions, they look for ways to make themselves appear environmentally friendly. This is called green marketing.

As a journalist, you need to learn to spot what a business really means by its green marketing.

Greenwashing is when a brand makes itself seem more sustainable than it really is, as a way to get consumers to buy their product. For example, let’s look at fashion, an industry that is responsible for between 2 and 8% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

In the absence of environmental legislation around the fashion industry a business might get themselves certified under a sustainability certification scheme — these are standards developed by governments or industry groups or NGOs to measure such things as energy efficiency or processes that are low carbon or carbon neutral. There are more than 100 different such certification programs.

Companies tout these certifications. But a 2022 study by the Changing Markets Foundation (CMF) found that the standards set by the majority of the 10 or more popular certification initiatives for the fashion industry aren’t difficult to meet and lack accountability.

Artificial claims about sustainability

Fast fashion relies on cheap synthetic fibers, which are produced from fossil fuels such as oil and gas. And while you might assume that clothing with labels such as “eco” or “sustainable” might have fewer synthetics, you’d unfortunately be wrong.

Another study by CMF found that H&M’s “conscious” clothing range, for example, contained 72% synthetics — which was higher than the percentage in their main collection (61%). And it’s not just H&M. While the same study found that 39% of products made some kind of green claim, almost 60% of these claims did not match the guidelines set out by the UK Competition and Markets Authority.

The same is happening in the meat and dairy industry. Companies say they are reducing their environmental footprint by engaging in “regenerative agriculture”, a farming approach that aims to restore and improve ecosystem health. They argue that it reduces greenhouse gas emissions and helps store carbon in the soil.

But relying on carbon storing in soil is not enough. An article in Nature Communications found that around 135 gigatonnes of stored carbon would be required to offset the emissions that come from the agriculture sector. This is roughly equivalent to the amount of carbon lost due to agriculture over the past 12,000 years, according to CMF.

But companies grab onto these empty promises, perhaps knowing that the general public might only see regenerative agriculture and other “green narratives” as promising.

Look for real solutions to climate change.

For example, Nestlé tells their customers that it is addressing the carbon footprint of the agriculture industry by supporting regenerative agriculture, stating on its website that in 2024, some 21% of the ingredients they source come from farmers adopting regenerative agriculture practices.

When you understand that regenerative agriculture is not the solution it has been made out to be, only then can you see through Nestlé’s branding.

So how can you spot greenwashing?

Let’s say you saw a press release from a company in an industry that has historically relied heavily on fossil fuels. It tells its readers that it plans to be carbon neutral by a certain date, or that it’s using recycled materials for a large portion of its production, or that its future is “green”.

You might first wonder, is this an example of how companies are moving away from fossil fuels and towards a green future? How can you tell?

1. Be skeptical.

When something has to tell you that it is green, it might not be. Start your investigation right there.

For example, if you were looking at Nestlé’s regenerative agriculture campaign, you would need to find out what regenerative agriculture is and how much it is indeed reducing greenhouse gas emissions. You can do this by starting with a good Google search: e.g “regenerative agriculture and greenhouse gas emissions”.

Once you click on a number of articles that report on this topic, you’ll be able to read about the different studies and data into the topic. Follow the sources used when an article cites a study or data. The article should hyperlink or list the sources. But those hyperlinks might take you to other secondary sources — other articles that cited the same data.

For example, an article might cite this statistic: sustainability certifications increase consumer willingness to pay by approximately 7% on average. The article might cite as the source this study published in the journal Nature. But that article isn’t the original source of that data. It came from a 2014 study published in the Journal of Retailing.

So try to find the primary source and see how credible or reputable it is. Who conducted the research in the first place?

If you wanted to find out what H&M’s “conscious” range really meant, you would start by looking at H&M’s website and reports to look further into their claims. Then, follow those claims.

2. Research the wider industry.

Whether you’re reporting on fashion, agriculture or any other industry, look into where its emissions are coming from, which companies are claiming what and what the evidence says needs to be done in order for these industries to reduce their emissions.

Providing context is important. What percentage of global greenhouse gas emissions is this industry responsible for? Is it getting better or worse? What legislation is in place to reduce emissions from these industries? In order for you and your audience to understand the greenwashing of any company, this background information is vital.

3. Go straight to the company.

Once you’ve conducted some initial research, follow up with the company if you are using it as an example or focus for your article. On Nestlé’s website, for example, you can find contact details for their communications, media or PR department. Send them an email saying something like the following:

“I am writing an article on regenerative agriculture and I’ve found some studies that show that soil sequestration through these practices are in fact not enough to be a real climate solution. Can you please provide me with a comment on what Nestlé thinks about this?”

They might not answer, but that also says a lot. If they don’t reply to you after one or two follow-up emails, you might try calling them.

If you try several times and in different ways to contact them and they failed to respond, you can state that in your article. That way your readers know you made the effort.

Claims from corporations that they are doing all they can to help the planet are easy to make. But if we really want to slow down climate change, significant efforts have to be made. And it is the role of journalists to hold companies to account for the claims they make.

Questions to consider:

1. What is “greenwashing”

2. What is one example of greenwashing?

3. What criteria do you use when deciding whether to buy a company’s product?

-

When young girls pay the cost of climate change

Jaffarabad, Balochistan: When floodwaters swept through Shaista’s village in 2022, they didn’t just take her family’s home and farmland, they also took away her childhood. Just 14 years old, Shaista was married off to a man twice her age in exchange for a small dowry.

Her father, a daily wage laborer, said it was the most painful decision he has ever made.

“I didn’t want to do it,” he said, his eyes fixed on the cracked earth where his fields used to be. “But I have four other children to feed and no land to farm. We lost everything.”

Stories like Shaista’s are becoming increasingly common across Balochistan, Pakistan’s poorest province. In 2022, devastating floods there driven by record-breaking monsoon rains and accelerated glacial melt linked to climate change, displaced over 1.5 million people.

There is worldwide recognition that extreme weather events — not just floods, but drought, heatwaves, tornados and hurricanes — are becoming more frequent and less predictable as the planet warms. These events have devastating and long-term consequences for people in poor regions.

Young girls as assets

In districts like Jaffarabad and Chowki Jamali, the aftermath of the disaster has left families grappling with deepening poverty, food insecurity and crushing debt. For many, marrying off their young daughters is no longer just a tradition, it’s a form of survival.

A 2023 survey by the Provincial Disaster Management Authority reported a 15% spike in underage marriages in flood-affected regions. Child rights activists warn that these numbers likely underestimate the scale of the crisis, as most cases go unreported.

“In flood-hit areas, families are exchanging their daughters to repay loans, buy food or simply reduce the number of mouths to feed,” said Maryam Jamali, a social worker with the Madad Community organization. “We’ve documented girls as young as 12 being married to men in their forties or fifties. This isn’t about tradition anymore, it’s desperation.”

Bride prices, once a source of negotiation and family prestige, have plummeted due to the economic collapse. Activists report instances where girls are married for as little as 100,000 Pakistani rupees (roughly US$360), or in some cases, simply traded for livestock or debt forgiveness.

“There are villages where girls are married off like assets being liquidated,” said Sikander Bizenjo, a co-founder of the Balochistan Youth Action Committee. “It’s not just a violation of rights, it’s a systemic failure rooted in climate vulnerability, poverty and legal gaps.”

Marriage as debt payment

In Usta Muhammad, another flood-ravaged district, 13-year-old Sumaira (name changed) was married off just weeks after her family’s mud house collapsed. Her parents received 300,000 rupees (a little over $1,000) from the groom’s family, which they used to rebuild their shelter and repay moneylenders.

Now pregnant, Sumaira, has dropped out of school and rarely leaves her husband’s house.

“I miss my friends and school,” she told us softly. “I wanted to become a teacher. But my parents said there was no other way.”

Child marriages like Shaista’s and Sumaira’s carry lasting consequences: early pregnancies that endanger both mother and child, disrupted education, psychological trauma and lifetime economic dependence.

A study following the 2010 floods found maternal mortality rates in some affected regions were as high as 381 per 100,000 live births, one of the highest in the world.

“These girls are thrust into adult roles before they’re ready,” said Dr. Sameena Khan, a gynecologist in Quetta. “They face dangerous pregnancies, and many have no access to medical care. Their childhood ends the moment they say ‘yes’ or are forced to.”

Giving girls an alternative to marriage

The crisis unfolding in Balochistan is not unique. Across the world, climate shocks and civil strife are causing displacement that intensifies the risk of child marriage.

In 2024, News Decoder correspondent Katherine Lake Berz interviewed 14-year-old Ola, who nearly became a child bride after her Syrian family, displaced by war and facing severe poverty, began arranging her marriage to an older man. But before that coil happen, Ola was able to enroll in Alsama, a non-governmental organization that provides secondary education to refugee girls. In less than a year, she was reading English at A2 level.

Alsama, which has more than 900 students across four schools and a waiting list of hundreds, has been able to show girls and their parents that education can offer an alternative path to security and dignity.

In Balochistan, the absence of legal safeguards compounds the crisis. The Sindh province banned child marriage in 2013 under the Sindh Child Marriage Restraint Act which set the legal age at 18 for both girls and boys. But Balochistan has yet to enact a comparable law.

Nationally, Pakistan remains bound by the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, which requires nations to end child marriage but enforcement remains patchy. And Pakistan is not one of the 16 countries that have also signed onto the Convention on Consent to Marriage, Minimum Age for Marriage and Registration of Marriages, which forbids marriage before a girl reaches puberty and requires complete freedom in the choice of a spouse.

Pakistan needs to reform its laws, said human rights lawyer Ali Dayan Hasan. “Without a clear provincial law and mechanisms to enforce it, girls are at the mercy of social pressure and economic collapse,” Hasan said. “We need legal reform that matches the urgency of the climate and humanitarian crises we are facing.”

Attempts to introduce child marriage laws in Balochistan have repeatedly stalled amid political resistance and lack of awareness. Religious and tribal leaders argue that such laws interfere with cultural norms, while government officials cite limited administrative capacity in rural areas.

Bringing an end to child marriages

The solution, experts agree, is multi-pronged: legal reform, economic recovery and access to education.

“We can’t end child marriage without rebuilding livelihoods,” said Bizenjo. “Families need food, land, healthcare and hope. If they can’t survive, they’ll continue to sacrifice their daughters.”

Grassroots organizations like Madad and Sujag Sansar provide vocational training, safe shelters and legal awareness sessions in flood-affected areas. In one case, Sujag Sansar intervened to stop the marriage of 10-year-old Mehtab in Sindh, enrolling her in a sewing workshop instead.

UNICEF estimates that child marriages could increase by 18% in Pakistan due to the 2022 floods, potentially reversing years of progress. The agency is urging governments to integrate child protection into climate adaptation and disaster relief programs.

“Girls must not be forgotten in climate response plans,” said UNICEF Pakistan’s representative Abdullah Fadil. “Their future cannot be the cost of every flood, every drought, every crisis.”

Back in Jaffarabad, Shaista now lives with her husband’s family in a two-room house. Her dreams of becoming a doctor have faded, replaced by household chores and looming motherhood. “I wanted to study more,” she said. “But now I have to take care of others.”

Questions to consider:

1. How does the marriage of young girls connect to climate change?

2. How can societies end the practice of child marriage?

3. Why do you think only 16 countries have signed the UN treaty that requires consent for marriages?

-

Can the world wean itself off petroleum?

It has been just six years since the Paris Climate Agreement set a race against time to rein in global heating. But the Earth is sending ever-harsher signals of alarm.

When the accord was signed, we were on course for global heating of 4°C from the start of the industrial era to the end of this century. Now the figure is around 2.7°C. So something has been achieved, but relative safety comes at no more than 1.5°C.

There is still a gap between the policies put in place over the past six years and what is needed to achieve that lower figure, the International Energy Agency (IEA) said in its annual outlook, published in October.

Yet we know what to do: substitute renewable energy for the power we get from fossil fuels by mid-century; decarbonize industry and adapt land-use to trap carbon in soil and plants; adapt our means of transport and our growing cities to use less energy; and protect marine areas to enhance carbon absorption in oceans.

“Two parallel and contradictory processes are in play,” wrote environmentalist and author George Monbiot in a Guardian opinion piece on November 3. “At climate summits, governments produce feeble voluntary commitments to limit the production of greenhouse gases. At the same time, almost every state with significant fossil reserves … intends to extract as much as they can.”

Everything depends, he concluded, on which process prevails.

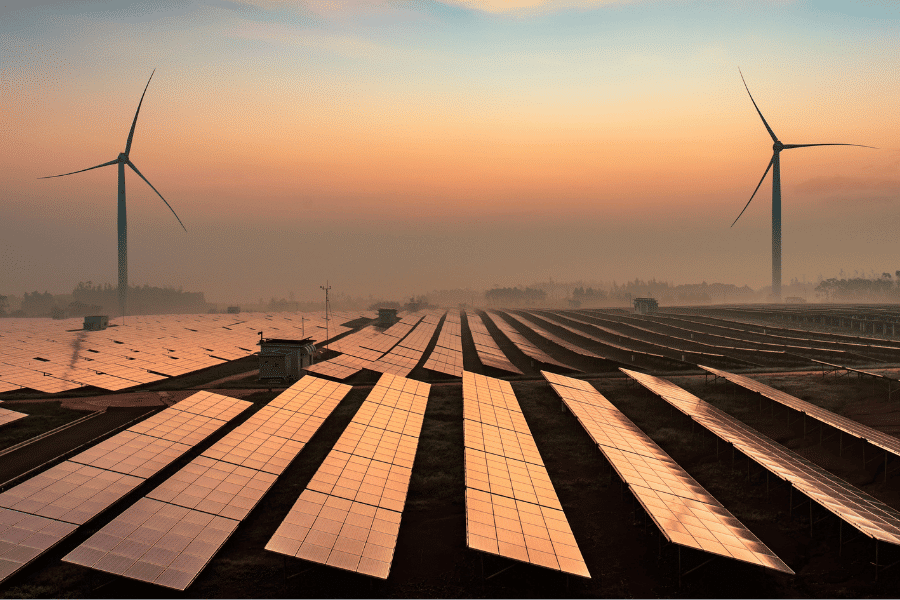

Making strides in renewable energy

Similar tensions are in play at industrial and economic levels. On the plus side, there is now a surprisingly strong backstory in renewable wind and solar energy, particularly solar, and particularly in the United States, the heaviest polluter historically per person, and China, the biggest polluter in absolute quantities of its emissions.

The energy crisis resulting from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine last February has prompted policies that will boost clean energy, the IEA added in its World Energy Outlook, which projects trends out to 2030.

While the crisis has created a temporary upside for coal, in the long run, production of renewable energy will outpace the production of energy derived from fossil fuels, the report said.

Another positive sign is the nascent hydrogen industry.

Widely occurring and carbon-free, this gas could decarbonize long-distance travel and industries that are heavy emitters. Producing it without carbon emissions implies using intermittent renewable energy when it is over-abundant, a virtuous circle.

However, none of this is yet at industrial scale — barring a few hydrogen-powered trains. Not all claims for hydrogen can be borne out, and it is not yet a viable financial concern.

There is a significant plus on the political front with the election of Luiz Ignácio Lula da Silva as Brazil’s next president. He promises to end the record deforestation of the Amazon under his predecessor, Jair Bolsonaro, and is to take office in January.

But there is no slowdown in fossil fuels.

Yet investment in fossil fuels still dwarfs cash flowing into renewables, even though they offer economic advantages. The United States, for example, has ploughed over $9 trillion into oil and gas projects in Africa since it signed the Paris Agreement, The Guardian found.

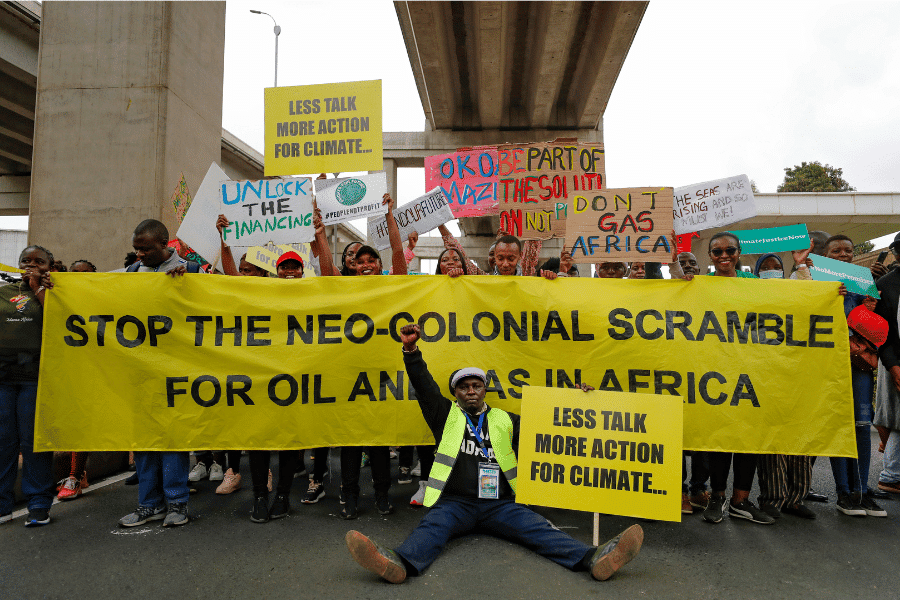

Africa, a continent starved of cash for energy but with vast potential for solar power, is now under pressure — including from international oil companies operating in its national parks — to exploit its fossil fuel resources just to bring electric power to its people.

The fossil fuel industry’s damage doesn’t end there. There has been drastic under-counting of carbon emissions, a new tracking tool backed by former U.S. Vice President Al Gore has found. Oil and gas companies have underestimated their emissions threefold, Gore said when launching the tool at the United Nations Climate Summit (COP 27) in Egypt this month.

“For the oil and gas sector it is consistent with their public relations strategy and their lobbying strategy. All of their efforts are designed to buy themselves more time before they stop destroying the future of humanity,” The Guardian quoted Gore as saying.

Investing in Africa

Across the world, policies are in place to invest over $2 trillion in clean energy by 2030, half as much again as today, led by the United States and China, but also including the European Union, India, Indonesia and South Korea, according to the IEA.

In the United States, solar was already becoming the star of the new energy scene, according to an annual report from Berkeley National Labs. The country added 1.25 terrawatts of solar capacity in 2021. That’s more than the installed solar capacity in the entire world, which reached 1 terrawatt in early 2022.

That was before the Biden Administration enacted the Inflation Reduction Act, which brings extra impetus for the sector. The United States plans to add 2-1/2 times its existing solar and wind capacity every year between now and 2030 and grow its fleet of electric vehicles seven-fold, the IEA said.

At the same time, Africa is desperate for energy investment.

To provide access to electricity for its population, the continent would need $25 billion per year, the IEA said in its annual Africa Energy Outlook, published in June. “This is around 1% of global energy investment today, and similar to the cost of building just one large liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminal,” it said.

The continent has 60% of the world’s best solar resources but only 1% of installed solar photovoltaic capacity. This is already the cheapest source of power in many parts of Africa and would outcompete all other energy sources across the continent by 2030, the IEA said.

The energy watchdog projects that solar, wind, hydropower and geothermal energy would provide over 80% of new power generation capacity in Africa by 2030. No new coal-fired power plants would be built once those now under construction are completed. Half the cost of adding new solar installations out to 2025 could be covered by investments that would otherwise have gone into discontinued coal plants.

Yet this assessment leaves out the plans for increased oil and natural gas developments on the continent.

Pressure from energy companies

A report just published by Rainforest UK and Earth Insight 2022 found that the area of land allocated across Africa for such developments is set to quadruple under existing plans. That report focuses on the Congo Basin, but in East Africa, French oil major TotalEnergies is pushing ahead with a large-scale oil project and trans-continental pipeline in Uganda.

A first cargo of liquefied natural gas has just left Mozambique after multiple delays caused by an insurgency in the region of the gas field, in a venture involving several oil companies.

These oil and gas projects would lock the continent into fossil fuels for decades to come and blow a hole in the bid to keep global heating to no more than 1.5°C.

These energy projects have wide support among African leaders, who contrast the immediacy of such investments and their benefits for their countries with the reluctance of Western nations to put up the finance agreed over a decade ago for energy transitions and preservation of biodiversity.

African environmentalists question the wisdom of this carbon bomb. But it is hard to dismiss the idea that broken promises by the countries that have caused the climate crisis has driven Africa into the arms of the fossil fuel industry.

TotalEnergies’ CEO Patrick Pouyanné argues that the world cannot quit fossil fuels before it has alternative sources of energy.

“The mistake being made now is to think that the solution for the climate is to abandon fossil fuels,” he said in an interview with French TV station LCI on November 17. “The solution is first to build the new decarbonized energies that we need.”

“If you do both at the same time, what happens?,” Pouyanné said. “Exactly what you reproach us for — prices rise because of the rarity of supply, because the demand for oil is not falling.”

The monopoly power of fossil fuel firms

These energy companies have long fought the switch from fossil fuels to renewables.

Half a century ago, Total concealed a report it had commissioned that clearly explained how burning fossil fuels would cause global heating and the consequences we are seeing today.

Other oil and gas companies, notably Exxon, acted similarly and responded to their findings by funding climate-denying think tanks and political lobbyists.

More recently, as the evidence mounted, they turned their attention to lobbying for exemptions, even though the scientific consensus demands that to achieve the 1.5°C limit on warming, there can be no new oil, gas or coal exploration or extraction.

A record number of fossil fuel lobbyists attended this month’s climate summit in Egypt (see the graphic here).

Fossil fuels no longer make economic sense.

The sector is a good example of reality flouting economic theory, which teaches that if a new technology reaches a point where it outcompetes an existing one, the new technology will replace the older one.

This should be happening with solar versus coal, oil and gas — and indeed is predicted to happen by 2050. Meanwhile, harmful emissions continue to rise.

Energy markets and the fossil fuel firms themselves do not obey basic economics for the simple reason that they are monopolies with the power to skew conditions in their favor.

The oil producers’ monopoly, in the form of OPEC, has controlled production to keep prices higher for decades. In the 1990s, the big Western oil companies went through a frenzy of mega-mergers that created today’s top five — Shell, ExxonMobil, BP, Chevron, and ConocoPhillips — whose sheer size gives them disproportionate bargaining and lobbying power.

Now activists are trying to gain support for a Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty as a way of reining in the root cause of the climate emergency. The initiative was put before the United Nations in September and the COP 27 climate summit in November.

“Will you be on the right side of history? Will you end this moral and economic madness?” Ugandan climate activist Vanessa Nakate asked global leaders at the summit.

On that, the jury is still out.

Landmark deal opens way for loss and damage fund

It has taken 27 climate summits, but the COP 27 in Egypt finally managed to pull out an agreement to set up a specific fund to aid poor countries hit by damage caused by climate disasters. The deal was approved on November 20 after a marathon negotiating session.

The proposal had been fought tooth and nail by the rich industrialized countries whose emissions have fostered global heating, stirring resentment among poorer countries who have suffered the most extreme consequences and have the least ability to mitigate the damage.

Details will be hammered out over the coming year, and there is as yet no money in the fund. It was nevertheless a major step forward.

However, the final agreement failed to call for phasing out all fossil fuels and for warming emissions to peak by 2025, both heavily opposed by oil-producing countries, raising fears that the goal of limiting warming to 1.5°C by mid-century will not be achievable.

Questions to consider:

1. Where is a major boom in solar energy taking place?

2. What is Africa’s energy dilemma?

3. Why do you think fossil fuel majors have so much influence?

-

Saying goodbye to our glaciers

Across the world two billion people — around a quarter of the world’s population — depend on glaciers for water to irrigate fields for agriculture, provide drinking water and to generate electricity.

But these glaciers are melting before our eyes.

Consider that 10% of Iceland is covered by glaciers but that is 1% less than a decade ago. That percentage will continue to decrease as the rate of change due to global warming has become dramatic.

Glaciers are so iconic in Iceland that when one collapses, people hold a funeral.

It’s a ceremony created for humans to make people aware about the urgency of global warming. And it’s a poetic way of marking the end of one of nature’s most inspiring creations.

A land where ice is prized

The first funeral for a glacier took place in 2019. It was for Okjökull glacier, the smallest glacier in a land that is dominated by ice and snow.

Okjökull glacier, popularly known as Ok, was only a modest 15 square kilometres big and had been shrinking for decades. Icelanders regarded diminutive Ok with affection, even making it a character in children’s book.

So the emotional impact of watching Ok vanish was felt not only by the locals who had grown up with the glacier, but across Iceland. Icelanders are brought up learning songs and sagas about their spectacular island. The snowpack of their glaciers creates the wild rolling rivers and massive waterfalls throughout the island before the flow tumbles into the stormy North Atlantic.

Now on the hill which had been covered by Okjökull is a rock with a brass plate with urgent words from Icelandic poet Andri Snær Magnason.

A LETTER TO THE FUTURE

Vatnajökull ice cap and parts of Hofsjökull ice cap, Iceland in September 2022. (Credit: Pierre Markuse via Wikimedia Commons)

Ok is the first Icelandic glacier to lose its status as a glacier. In the next 200 years all our glaciers are expected to follow the same path.

This monument is to acknowledge that we know

what is happening and what needs to be done.

Only you will know if we did it.Ice loss in Iceland

Tiny Okjökull was nothing compared to the largest glacier in Iceland — and in Europe — the Vatnajökull ice cap.

Despite its mass, scientists estimate that nine million litres of Vatnajökull’s glacial ice are being turned into water every minute.

The lakes and ice lagoons downstream of Vatnajökull, filled by meltwater, are bigger every year as the glacier itself shrinks.

So should there be funerals for glaciers?

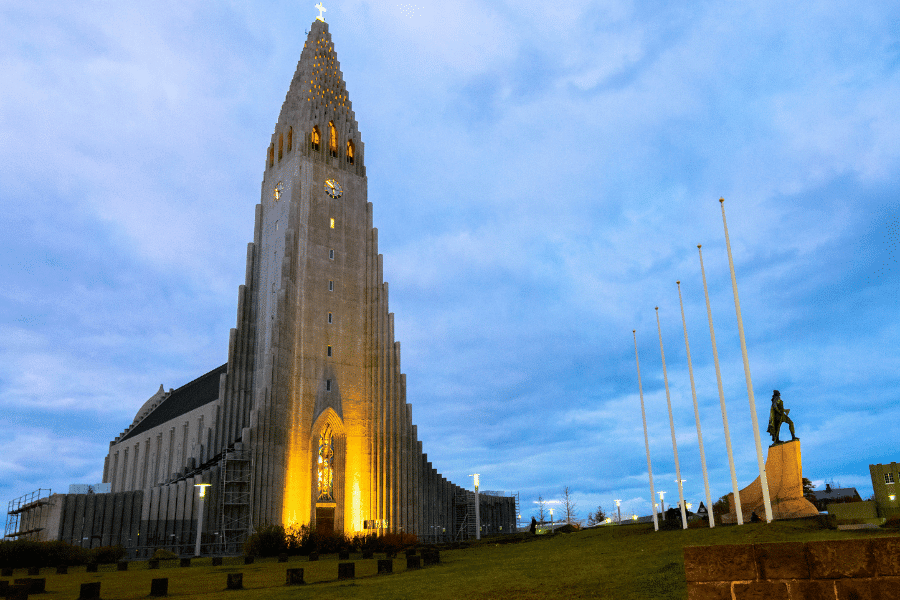

Sigurdur Arni Thordarson, the pastor of Hallgrímskirkja Church in Iceland thinks so. His church was built to resemble the mountains and glaciers of Iceland and dominates the Reykjavík skyline.

“For humans, the loss of a glacier is a real loss,” Thordarson said. “People who have a deep understanding and awareness of interconnectedness of life really feel the necessity of expressing the grief.”

Snow melt in the Alps

It seems a widespread sentiment. A few months after the ceremony in Iceland, hikers, many dressed in black, gathered on Pizol glacier in the Swiss Alps to listen as a priest gave a funeral service.

Another ceremony followed in 2020 for Clark Glacier in Oregon and soon after on a Mexican glacier named Ayoloco by the Aztecs. The Mexican geologists and ecologists who marked the day used the words written by Andri Snær Magnason that commemorate Okjökull.

Crossing into another culture, Buddhists monks in Nepal held an ‘ice funeral’ in the Himalayas in May 2025 for Yala Glacier which had shrunk by two thirds in the past several decades. Attended by locals and climate scientists they gathered under traditional prayer flags across from the last visible ice. Even Yala’s altitude over 5,000 metres was no protection against deglaciation

Two granite stones now mark the spot of the ceremony. One with the words of Magnason from Iceland, the other with an inscription from Nepali poet Manjushree Thapa:

Hallgrímskirkja Church in Reykjavík, Iceland. (Credit: Mattias Hill via Wikimedia Commons)

Yala, where the gods dream high in the mountains, where the cold is divine.

Dream of life in rock, sediment, and snow, in the pulverizing ofice and earth, in meltwater pools the colour of sky.

Dream. Dream of a glacier and the civilizations downstream.In all these commemorations, Magnason’s alarm from Iceland have been echoed:

…We know what is happening and what needs to be done. Only you will know if we did it.

The Third Pole

The glaciers in the Himalayas are sometimes called the ‘Third Pole’ because they account for the most ice after the Arctic and Antarctica.

Around the world glaciers are melting faster than ever recorded but the Himalayas are warming at a higher rate than the global average, up to 65% faster. The Himalaya glaciers feed some of the great rivers of Asia — the Ganges, Indus, Brahmaputra and Yangtze rivers which flow through some of the most populated areas on the planet.

The consequences of disappearing glaciers are starting to be felt. Mexican climate scientists who attended the Ayoloco ceremony pointed out that “without large ice masses on mountain peaks temperatures will increase.”

All of our planet was created by massive geologic forces. Those forces are more easily observable in Iceland, being one of the newest land masses to be created on Earth. It is an island nation that was created by volcanoes but sculpted and defined by glaciers. It may be fitting that, in addition to the first glacier funeral ever held, the first Glacier Graveyard was created in 2024, to mark extinct glaciers and provide a reminder of what is at stake.

The glaciers remembered were taken from the first Global Glacier Casualty List. Soon after, the United Nations declared 2025 the International Year of Glacier Preservation. Now, all fifteen tombstones carved from ice to mark those vanished glaciers have melted.

Questions to consider:

1. Should glaciers, like some rivers which have been granted legal rights, be regarded as living creatures?

2. Does a ceremony like a funeral provide an inspiration for climate activism?

3. What natural formations or environmental places are important to you?

-

A pipeline of prosperity or plunder

In the sticky heat of an April afternoon in Kampala, Uganda nine university students stood outside the headquarters of Stanbic Bank, their voices raised in protest. It is a sound that has echoed for more than half a decade.

Their signs called for an end to the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP), a $5 billion project: 1,443 kilometers of 24-inch wide, heated and buried steel ambition, snaking from Uganda’s oil-rich Lake Albert basin to the Tanzanian port of Tanga on the Indian Ocean. Before the hour was out, they were in police custody.

The government has hailed the project as a pillar of economic transformation. But critics — students, activists, and environmental groups — argue it will displace communities, threaten biodiversity and entrench a model of development that sidelines democratic participation. Dissent has been met with arrests, surveillance and a steadily shrinking civic space. The protests, though often silenced, persist, challenging a narrative that equates oil with progress.

Five days after the arrests, in the same city, a different kind of statement was made. At the Eleventh Africa Regional Forum on Sustainable Development, held from April 7th to 11th, delegates issued a call that seemed — if only for a moment — to resonate with those voices on the street.

The route of the East Africa Crude Oil Pipeline. Wikimedia Commons

Members of the UN Economic Commission for Africa urged a shift away from exporting raw materials and toward value addition through manufacturing and industrialisation. Mining, they said, and the export of cash crops like cocoa, tea and coffee must no longer be the end of the story, but the beginning of something built to last.

Shouting into the void

For the students arrested, whose protests have long been dismissed as anti-developmental by a government intent on progress-by-pipeline, this sudden harmony of rhetoric might feel like vindication — if only the delegates meant what they propose.

The students may have been shouting into a void, but the echoes resonate with a wider pattern etched deep into the continent’s political and economic architecture. Back in 2016, journalist Tom Burgis, author of “The Looting Machine”, put it in a 2016 interview with CNN: “There is a pretty straight line from colonial exploitation to modern exploitation.”

Burgis has long documented the mechanisms of resource extraction in Africa and pointed to the lingering dominance of oil and mining multinationals — entities that, decades after independence, still wield economic and political influence akin to that once held by colonial administrations.

Zaki Mamdoo, a South African climate justice activist and campaigner with the Stop EACOP coalition, agrees with Burgis’s notion of modern resource imperialism — only now, the governors wear suits and operate through shareholder meetings.

“How come TotalEnergies owns 62% shareholding power, while Uganda and Tanzania hold just 15% each?” he said.

Partnership or plunder?

The numbers speak for themselves. The French oil giant TotalEnergies, with Chinese partner CNOOC in tow, controls the lion’s share of the project. Uganda, the country from which the oil originates, has been cast in the role of host, not owner. Tanzania, whose land will bear the pipeline’s longest stretch, fares no better. For Mamdoo and many others, this is not a partnership; it’s a palatable version of plunder.

“This is not African-led development,” Mamdoo said. “It’s an extractive model dressed up in nationalist rhetoric.”

To critics, EACOP is a 21st-century replay of old patterns — resources extracted with little local benefit, profits flowing abroad and environmental costs left with the people. What’s different now is the packaging: marketed as part of an energy transition and a driver of economic empowerment. But on the ground, the reality is displacement, disrupted livelihoods and fragile ecosystems in the pipeline’s path.

According to EACOP’s official figures, more than 13,600 people have been affected, with 99.4% of compensation agreements signed and paid. But activists argue the numbers mask deeper issues — slow and uneven compensation, uprooted communities and long-term uncertainty.

“The real number is far higher,” said Mamdoo. “We’re talking well over 100,000 directly impacted — and many more indirectly. But of course, Total reports a few tens of thousands.”

Differing views on sustainability

From Uganda’s farmlands to Tanzania’s reserves, the pipeline cuts through forests, wetlands and biodiversity hotspots — what critics see as a trail of ecological and human disruption beneath a polished PR campaign.

By underreporting those impacted, critics argue, multinationals shrink their obligations — and their compensation budgets. The payments, when they come, have been slow, sporadic and, in some cases, still absent. Yet the construction rolls forward.

To Morris Nyombi, a Ugandan activist now living in exile for his work opposing EACOP, the narrative of compensation is as hollow as it is dangerous.

He watches from afar as national television and international media spotlight a few smiling beneficiaries — residents celebrating a new house, a fresh coat of paint, a sense of reward.

Nyombi sees what isn’t shown. “Let’s state facts, when minerals are found somewhere, just know that’s lost land — it becomes government property,” Nyombi said. “And to the select few given houses, what then? You’re an agriculturist. Giving you a house somewhere else doesn’t mean giving you land to till. You’re killing a way of life.”

A pipeline of displacement

Without farmland, families are forced to sell off whatever land remains and move to towns and cities in search of new beginnings.

“They end up in Kampala renting, looking for what to do,” Nyombi said. “It’s displacement without a plan. Progress for someone else.”

Farmers who were near the pipeline’s path are now scattered across the Uganda-Congo border, Nyombi said. “They were duped into compensation. When they resisted, they started receiving threats. Husbands arrested. The women and children forced to run, to hide. That’s the reality.”

These, Nyombi said, are the people the government never talks about. They don’t show up in speeches or glossy brochures about development. But their lives tell the story better than any pipeline prospectus ever could.

But speaking out against EACOP is dangerous. “It’s a gamble with one’s life,” Nyombi said. Being an activist, he adds, is a kind of social exile. Most organizations won’t hire you — won’t even stand next to you. In much of Africa, governments don’t hesitate to hit below the belt.

A lake that sustains life

Nyombi has been on the government’s radar since 2020. He has been threatened and surveilled and been the subject of smear campaigns. As a result, he stepped back from frontline organizing.

But what if the project were perfectly managed with strict environmental safeguards, zero corruption and full compensation? Would that make EACOP justifiable?

Mamdoo said that isn’t what is happening, citing reports of oil slicks on Lake Albert and elephants rampaging villages. The very question betrays a fundamental misunderstanding, Mamdoo said. Environmental damage isn’t a hypothetical risk, it’s already unfolding.

“If oil spills hit Lake Victoria—the region’s largest freshwater body—over 40 million people would be poisoned,” he said.

Lake Victoria sustains agriculture, fishing, drinking water, and transport across Uganda, Tanzania and Kenya. It’s East Africa’s largest inland water body — and the source of the Nile. Yet while project backers point to EACOP’s technical safeguards, critics like Mamdoo argue that no pipeline cutting through seismically active zones, protected ecosystems and critical watersheds can ever be truly safe.

“You can’t just contain a pipeline,” Mamdoo adds. “You can’t plug all the holes when the system is built to leak — money, justice, land, people.”

Keeping oil where it is extracted

Supporters of the pipeline argue that projects like EACOP could open the door for substantial donations to tourism development and wildlife protection, especially in ecologically sensitive zones where the pipeline runs near or through national parks. The idea is that the extractive industry might fund preservation as part of its footprint.

But to Mamdoo, that premise is flawed from the start.

“What’s that compared to the 62% they’re taking?” Mamdoo asks. “You shouldn’t settle for peanuts when you own a resource.”

Being a funder, he adds, doesn’t make you the owner. Mamdoo would like to see the oil stay in Uganda. “We’d be having an entirely different conversation if the plan was to have our own refineries, process it locally, then sell the products to them,” he said.

Nyombi isn’t surprised that the government supports EACOP. Historically, leaders who stand up to corporations and the Global North haven’t lasted. “These multinationals don’t want an Africa that sees clearly,” Nyombi continues. “They want us manageable. If you open your eyes and demand real sovereignty, you become a threat to global stability.”

Taking on global establishment isn’t easy.

Some critics point to the case of Muammar Gaddafi, the Libyan leader who championed a gold-backed African currency and pan-African resource control before being toppled in a NATO-backed intervention. His fall, they argue, wasn’t just about domestic tyranny — it was about challenging the global status quo.

Yet among younger Ugandans, particularly students, the legacy of figures like Gaddafi is often blurred or reduced to villainy — taught more as a cautionary tale than a case study in resistance. The narratives they inherit are tightly curated. But still, a shift is happening.

Especially among those studying environmental science, Nyombi sees a growing restlessness.

“These students, they want to act,” Nyombi said. “They’re interested in ground action. But more than that — they’re asking deeper questions. They wonder, why keep planting trees that won’t grow?”

There’s a frustration with symbolic gestures — school-organized clean-ups, ceremonial tree-plantings — that often sidestep the policies creating the very destruction they’re meant to remedy.

“They’re starting to say, no, the problem isn’t the seedling. It’s the system. So why not challenge policy instead?” Nyombi said. “But to challenge policy, you have to get out there.”

That’s how the students who were arrested on 2 April while approaching Uganda’s Stanbic Bank came to act.

Taking protests to the front line

Mamdoo said that the protest was not just symbolic — it was strategic. Stanbic is one of the banks linked to funding the East African Crude Oil Pipeline. For the students, it was the front line.

“They’re trying to secure their future,” Mamdoo said.

But the bank saw it differently. Kenneth Agutamba, Stanbic Uganda’s country manager for corporate communications, defended the institution’s involvement.

“Our participation aligns with our commitment to a just transition that balances economic development with environmental sustainability,” Agutamba said. “The project has met all necessary compliance requirements under the Equator Principles and our Climate Policy.”

For the students, though, no statement or principle outweighs what they see as the theft of their future. Their protest, they insist, is not rooted in mere outrage. It’s anchored in a growing global reckoning: at least 43 banks and 29 insurance companies have declined to support EACOP, citing its environmental threats and human rights risks.

But despite the pressure from abroad, the pipeline — and the crackdowns — continue to move forward.

“That’s why we’re targeting the funders,” Mamdoo said. “If the money dries up, the project can’t survive.”

Dissent and disappearance

The students arrested will likely be released — this time. They’re lucky. Local papers spoke of them. Many others vanish into cells for months, even years, without trial — especially those without lawyers, or whose names never make it into the headlines.

If there’s a single line that captures the price of resistance, it might be Braczkowski’s blunt warning: “Any oil activist in Uganda will be sniffed out before Total.” Oil, he adds, has become Uganda’s gold — a lifeline that may help service the country’s mounting debt.

“That’s exactly the problem,” Mamdoo counters. “If all it does is pay off debt, what’s left for the people? There won’t be money for schools, for hospitals — just enough to keep the lights on in their offices.”

It’s been nearly a decade since EACOP was first proposed. Only now, as shovels hit soil and risks become real, has public scrutiny begun to catch up. And that, Mamdoo and Nyombi agree, is because of activism.

“Without it,” Nyombi said, “this would’ve gone quietly. Smoothly. Just another deal signed behind closed doors.”

But things aren’t moving as fast as they once were.

“Activism has slowed them down,” Nyombi adds. “It’s not moving at the pace they wanted.”

So what’s the real equation here? A pipeline backed by billions. A government banking on oil. A continent still clawing for control of its wealth. And in the middle — students, farmers, mothers, exiles — bearing the cost of asking the most dangerous question of all:

What if we said no?

Three questions to consider:

1. What is EACOP?

2. Why are many people in East Africa opposed to a pipeline that promises to bring money to the region?

3. If you were in charge of natural resources for Uganda, what policies would you put in place?

-

Can we de-stress from climate change distress?

Consider that BP, one of the world’s biggest oil companies, popularised the term “carbon footprint”, which places the blame on individuals and their daily choices.

Anger also comes up a lot, Robinson said, particularly for young people.

“They’re angry this is happening,” she said. “They’re angry they have to deal with it. They’re angry that this is their world that they’re inheriting and that all totally makes sense. It’s not fair to burden young people with this. It’s really important that they have support and action by adults in all kinds of ways throughout society.”

Working through our feelings

Then there’s sadness and grief.

“We have of course loss of life in many climate disasters,” Robinson said. “That’s really significant. And loss of habitat, loss of biodiversity, loss even of traditions and ways of life for a lot of people, often in Indigenous cultures and others as well.”

One of the most simple and effective ways we can deal with climate distress is by talking about it, and by giving young people the opportunity and space to do so.

“One of the hardest things is that people often feel really isolated,” Robinson said. “And so talking about it with someone, whether that’s a therapist or whether that’s in groups … just anywhere you can find to talk about climate emotions with people who get it. Just talk about climate change and your feelings about it.”

Having a space to discuss climate change and their feelings associated with it can help a young person feel understood. Talking about feelings in general, known as “affect labelling”, can help reduce the activity of the amygdala — the part of the brain most associated with fear and emotions — in stressful times.

Unplug yourself.

Unlimited access to the internet does allow young people to connect with like-minded people and engage in pro-environmental efforts, but the amount of information being consumed can also be harmful.

Climate change is often framed in the media as an impending environmental catastrophe, which studies say may contribute to this sense of despair and helplessness, which can lead to young people feeling apathetic and being inactive.

Robinson said that while you don’t need to completely cut out reading the news and using social media, it is important to assess the role of media consumption in your life. She suggested setting a short period of time every day where you connect to the media, then try your best to refrain from scrolling and looking at your phone for the rest of the day.

“Instead, look outside at nature, at the world we’re actually a part of instead of what we’re getting filtered through the media,” she said.

For some people, looking at social media around climate is a way of connecting with a community that cares about climate, so it can still be a useful tool for many people.

“Our nervous systems can get really hijacked by anxiety,” Robinson said. “We know that when mindfulness is a trait for people, when it really becomes integrated into who they are, that it does help. It’s associated with less climate anxiety in general.”

Take in the nature around you.

Studies show that mindfulness can improve symptoms of anxiety and depression. Robinson says this is partly due to it allowing us to be present with whatever feelings come up, that it helps us to stay centred throughout the distress.

It can be as simple as taking a mindful walk in a nearby forest or green space. While of course forests are helpful in absorbing carbon and reducing emissions, they can also help us reduce stress. Some studies have shown that spending more than 20 minutes in a forest — noticing the smells, sights and sounds — can reduce the stress hormone cortisol.

Robinson said that one of the more powerful things you can do is to band together with others.

“Joining together with other people who care and who can have these conversations with you and then want to do something along with you is really powerful,” she said. “We’re social animals as humans, and we need other people and we really need each other now during all of this. And it’s so important to be building those relationships if we don’t have them.”

It is possible that climate anxiety can increase when young people learn about climate change and the information is just thrown out there, Robinson said, and the opportunity to talk about emotions should be incorporated into learning.

“It is different than learning math, or learning a language,” she said. “It’s loaded with all kinds of threat. Kids need to know what to do with that because there is going to be an emotional response.”

Take climate action.

It has also been shown that action can be an “antidote” for climate anxiety and that education centred around action empowers youth, when providing ways of engaging with the crisis collectively.

Teachers can then help students connect their feelings with actions, whether that be in encouraging their participation in green school projects or on a broader level in their communities.

“That action, it helps, it really gives people a sense of agency and they know that they are making a difference,” Robinson said.

We need to come together, she said, not just to help us feel better, but to find solutions. “I really think that our connection, our systemic issues that we have, are so profound and they really push us away from each other in so many ways.”

Our societies often favour consumption over connection, she said. “As human beings we developed in the context of nature, evolutionarily,” she said. “We were immersed. We were part of nature, and we are still, but we have increasingly grown apart from that relationship.”

That changed over time. Now people spend little time in nature even though it’s often all around them.

“From an eco-psychological sort of point of view, we’re embedded in that system, and we’re harming that system because of that separation that’s developed,” she said.

Questions to consider:

1. What is “climate anxiety”?

2. What is the connection between climate anxiety and education?

3. How do you handle the stresses that you are under?

-

Decoder: The Paris (Dis)Agreement

The newspapers dubbed it “unprecedented”, “historic”, “landmark”.

Then-U.S. President Barack Obama called it a “tribute to strong, principled American leadership”.

When 195 countries came together nearly 10 years ago to adopt a legally binding agreement to try to avert the worst effects of climate change, it was considered a triumph of diplomacy and a potential turning point for the world. The deal that emerged is now so well-known it is referred to simply as “the Paris Agreement” or “the Paris Accords” — or sometimes just “Paris”.

But with a stroke — or several — of his black-and-gold pen, U.S. President Donald Trump has taken the United States out of the fight to stop global warming, casting the future of the pact and everything it hoped to accomplish into doubt.

Has the departure of the United States doomed the campaign to cut greenhouse gas emissions to failure? And if not, who will take up the torch Trump has cast aside?

Uncharted waters

The good news is that climate change experts believe the benefits of a transition to renewables — from energy independence to cleaner air — are so compelling the shift will go with or without the United States.

The bad is that Trump’s actions will give many countries and companies an excuse to leave the battlefield. And that may make it impossible to meet the Paris Agreement’s goal of holding temperature rises to well below 2 degrees Celsius.

Listing all the steps Trump has taken so far to undermine the climate campaign would take hundreds of words. So here are just a few.

Since 20 January 2025, the newly-minted U.S. government has:

• Withdrawn from the Paris agreement for the second time – joining the ranks of Yemen, Iran and Libya as the only countries outside the pact.

• Said the Environmental Protection Agency would look at overturning a 2009 ruling that greenhouse gases threaten the health of current and future generations – effectively gutting the agency’s legal authority to regulate U.S. emissions.

• Rolled back dozens of Biden-era pollution rules.

• Abandoned a deal under which rich countries promised to help poorer ones afford to make the transition to sustainable energy.

• Eliminated support for domestic and international climate research by scientists.

• Halted approvals for green energy projects planned for federal lands and waters.

• Removed climate change references from federal websites.

• Set the stage to fulfil Trump’s promise to let oil companies “drill, baby, drill” by declaring an energy emergency, which will allow him to fast-track projects.

Eliot Whittington, chief systems change officer at the Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership, said that the United States is entering genuinely uncharted waters.

“The Trump administration is making changes far in excess of its legal authority and drawing more power into itself and away from Congress, states and the courts,” Whittington said. “It is doing so in service of an explicitly ideological agenda that is hostile to much green action — despite the popularity of environmental benefits and high level of environmental concern in the U.S.”

Alibi for inaction

Trump has repeatedly — and falsely — called the scientifically-proven fact that mankind’s actions are leading to planetary heating a hoax. In November 2024, following the onslaught of deadly Hurricane Helene, he said it was “one of the greatest scams of all time”.

For a hoax, climate change is packing a painful punch.

Last year was the hottest on record, and yet even with countries touting net-zero gains, emissions also hit a new high. According to World Weather Attribution, the record temperatures worsened heatwaves, droughts, wildfires, storms and floods that killed thousands, displaced millions and destroyed infrastructure and property.

In other words, the need to curb emissions is only growing more urgent.

Alister Doyle, a News Decoder correspondent who authored “The Great Melt: Accounts from the Frontline of Climate Change“, believes Trump’s anti-green policies will slow but not stop the move away from fossil fuels.

“But while other nations will stick with the Paris Agreement, almost none are doing enough,” he said. “Trump’s decision to quit will provide an alibi for inaction by many other governments and companies.”

Voters look to their wallets

Ambivalence about net-zero policies had been on the rise even before Trump took office, stoked by populist political parties.

There are clear long-term economic benefits of the transition — from faster growth to the avoidance of costs linked to natural disasters. But Whittington said that the short-term sacrifices and infrastructure spending it will require have proven a tough sell when voters are facing difficult financial circumstances at home.

“After a global inflation shock post-pandemic, governments have little financial space to defray the costs of upfront investment and generally voters feel like they don’t have the space to take on additional costs, even as a down payment on a better future,” Whittington said.

This is further complicated by a powerful lobby against climate action led by oil and gas companies, which have devoted hundreds of millions of dollars to the effort. While most have also made public commitments to green goals, the sentiment shift has led several to abandon most or all of these in the past few weeks.

Whittington believes that, despite these setbacks, the energy transition will eventually gain enough momentum that even fossil fuel producers will be unable to step on the brakes. It will be led by multiple countries and propelled by a variety of forces.

Chief among these is the need in today’s politically fractured world for energy security: the guarantee a country will have access to an uninterrupted — and uninterruptible — supply of energy at a price it can afford. This is particularly important to countries dependent on imported energy.

China leads the way.

In its pursuit of energy self-sufficiency, China — both the world’s largest fossil fuel importer and the world’s top greenhouse gas emitter — has earned itself a less dubious distinction: it now leads the globe in the production of renewable energy and electric vehicles.

“The International Energy Agency says that China could be producing as much solar power by the early 2030s as total U.S. electricity demand today,” Doyle said.

Europe, meanwhile, has been on a quest to wean itself of Russian oil and gas and has rapidly increased its adoption of renewables. The United Kingdom, meanwhile, is currently the world’s second-largest wind power producer and plans to double capacity by 2030.

“Europe as a whole — including the UK — generally is leading the world in showing how to cut emissions and grow the economy,” Whittington said.

The United States, he added, will likely stay involved in areas where it holds a technical edge, such as battery development.

Even the Middle East will have an increasingly compelling motive for going green(er): the need for other sources of income as fossil fuel demand falls from a peak expected in 2030.

Public pressure itself may again become a driving force for change.

As hurricanes, wildfires, droughts, heatwaves and other climate-related disasters increase — and as a younger, more climate-aware generation finds its voice — voters may start worrying less about their personal finances and more about the future of the planet.

Three questions to consider:

1. What is meant by the “green economy”?

2. How can a government encourage or discourage climate action?

3. What, if any, changes to your lifestyle have you made to help our planet?