At first, Carolyn Atim thought the headaches she was experiencing were just the residual echoes of pregnancy. Consultations then indicated she had high blood pressure. Slight of frame, barely out of her twenties, Atim had given birth to a boy in 2013.

Nine months later, the headaches hadn’t gone away and she was feeling unrelenting fatigue. She brushed them off.

“I was so tiny,” she said. “And you know the perception that a tiny person doesn’t suffer from high blood pressure!”

Her doctor suggested she take some comprehensive tests. So she did them: renal function, liver function and complete blood counts. The verdict came as a blow. “You have end-stage kidney disease,” the specialist said.

Atim didn’t know where to place that phrase. End-stage. It sounded so final. “You look at yourself, and you’re told you have a chronic illness,” she said. “You see yourself dying. I had hallucinations of being buried. I saw myself in a coffin.”

The holistic costs of kidney disease

In Uganda, kidney disease is not just a medical condition — it’s a verdict with economic, emotional and systemic implications. The country is slowly clawing its way toward better care, thanks in part to pioneers like Dr. Robert Kalyesubula, one of Uganda’s first nephrologists.

When he began his profession 15 years ago, he was only the third in the nation. Today, there are 13 kidney specialists and two more are expected. That’s progress, but measured against a growing burden.

“About seven in every 100 Ugandans are living with kidney disease,” Kalyesubula said.

That translates to 7% or roughly 3.2 million people — a statistic that may not seem extraordinary at first glance. After all, the global burden is heavy.

A 2023 report in Nature Reviews Nephrology estimated that 850 million people — one in 10 worldwide — live with some form of chronic kidney disease. In the United States, the rate climbs to 15% of adults; in Europe, it ranges from 10 to 16% depending on the country.

But prevalence tells only part of the story.

Inequity in healthcare

In high-income countries, there are safety nets: screening programs, subsidised treatment and specialist care. In much of sub-Saharan Africa, the same illness unfolds without a cushion or warning.

The World Health Organisation already ranks chronic kidney disease among the top 10 causes of death globally. The trajectory is alarming. By 2040, researchers expect it to become the fifth leading cause of years of life lost, overtaking many cancers.

The drivers are familiar: longer life spans, surging rates of hypertension and diabetes and widespread neglect of early detection. In countries like Uganda, where comprehensive testing is still a luxury, the disease often makes itself known only when the body is in full collapse.

“Fifty-two percent of our patients come when they are already at stage five,” Kalyesubula said.

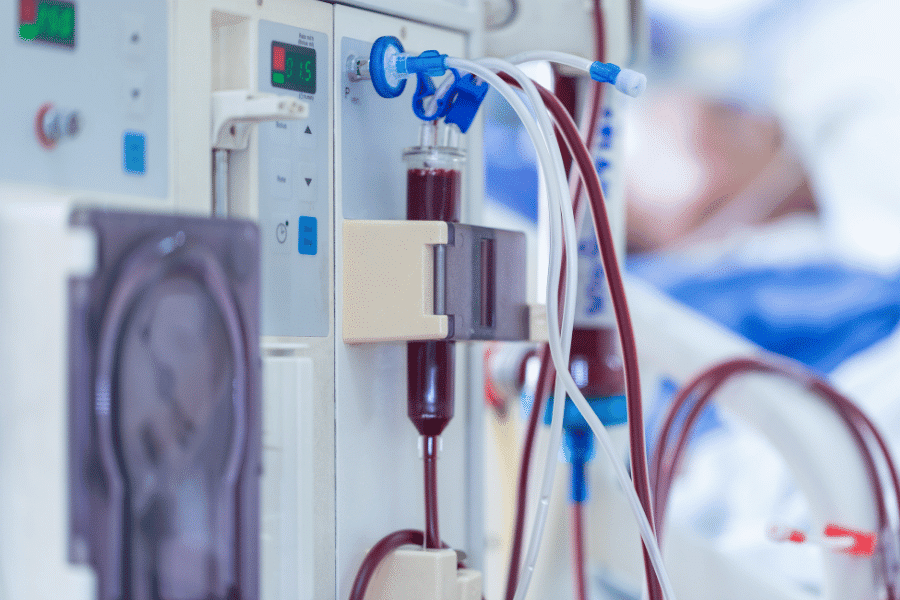

By then, treatment is no longer medical alone — it is economic. Stage five is the red zone: dialysis or death. Dialysis, in Uganda, will demand four million shillings per month — about US $1,100, cash on delivery — just to keep the body’s silent custodian from shutting down.

A transplant? That fantasy starts at 100 million shillings (about US $27,000). This, in a nation where only 1% of about 23 million working Ugandans earn more than a million shillings a month. Nearly half survive on less than 150,000 shillings.

An economic death sentence

In countries like Uganda, kidney failure isn’t just a medical crisis, it’s an economic death sentence. But Atim’s story didn’t end at diagnosis.

She found herself clawing at survival — medical appointments twice a week, pill regimens that bloated her cabine and a spiritual fog that refused to lift. Her saving grace came in a rare combination: a devoted husband, an unusually supportive employer and a doctor who didn’t just treat her but stood by her.

“Dr. Kalyesubula told me, ‘You’re still a young girl. Get me a donor, and we shall find the money. God will help us,’” she said.

Atim did find a donor. Her sister stepped forward. Her employer, moved by her story, urged her to go to the media — not to plead, but to make a case to headquarters for support. Her husband’s workplace did the same. Friends, colleagues, family — they all mobilized.

“I was lucky,” Atim said. “Other people go to the media to beg. For me, my company said, ‘Go, so we can help you.’”

A new lease on life

The transplant took place in India in 2015. The morning of the operation, someone unexpected showed up at her bedside.

“I opened my eyes, and there he was — Dr. Kalyesubula. I didn’t even know he had flown in. That humbled me,” she said. “He had seen the journey through.”

For Kalyesubula, his work is a calling. “One day I was with my family at school — visiting day,” he said. “I had promised my daughter I won’t work. But then I got this call — ‘You are the one who has to save me.’ I had to leave.”

Uganda now has over 300 dialysis machines — up from just three when Dr. Kalyesubula started — and more than 25 centers spread across the country.

Kidney care is expanding, even if slowly. Yet transplants within Uganda remain rare, and still rely heavily on partnerships with hospitals in India. The selection process is tight: donors must be related, young and a near-perfect match. Atim knows how slim her chances were.

“If Dr. Kalyesubula hadn’t insisted on a preemptive transplant, I would have gone on dialysis,” she said. “And with our income, that might have been the end.”

Instead, she got her life back. She’s gained weight. “From 40 kilos to 72,” she said, laughing. And she works full-time.

Their bond has grown beyond prescriptions and reviews. They speak quarterly, consult online and even banter like old friends. “We call each other ‘dear’ — like family,” she said. “We even joke now. He says he won’t compete with me again on weight loss — I always win.”

Expanding treatment for all

Kidney disease still looms in Uganda, but progress is undeniable. Over 300 dialysis machines now serve patients in multiple districts. Transplants are possible — though limited to close relatives — and awareness is growing.

Dr. Kalyesubula doesn’t mince words when it comes to the kidney’s role in the body. “If it’s not working well, you die,” he said. “Its importance is in making blood. Its importance is in removing toxins. Its importance is in controlling your blood pressure, regulating electrolytes, maintaining your internal environment — so that everything else can function at all.”

Think of it as the body’s meticulous custodian — part janitor, part electrician, part life support, he said. It scrubs the blood clean, balances the chemistry of survival and even directs traffic, ensuring oxygen-rich blood reaches the brain, the heart, the muscles. Without it, the delicate machinery of the body grinds to a halt.

But here’s the twist: Since only 7% of the country is living with kidney disease, he said, what are the rest doing that they’re not? Is it luck? Genetics? Or something more mundane?

The best treatment, it seems, is prevention. “Drink enough water, avoid excessive salt and alcohol, eat fruits and fresh foods, move your body — exercise — don’t take over-the-counter drugs carelessly,” he said. “And once you click 30 — at least do a body check-up once a year.”

Raising awareness

Prevention is simple and inexpensive advice, but ignoring it carries a steep price, especially in Uganda, where a kidney disease diagnosis can unravel the life of an ordinary working person faster than the disease itself.

That’s why Atim has become a leader in the silent, underserved world of kidney patients in Uganda, sharing her story when asked, opening up her pain so others might find their way out of theirs.

She’s become a relentless advocate for affordable medication, creating and distributing kidney disease awareness, chasing down funding and forging hospital partnerships, all in the name of accessibility. It’s a fight born of necessity. She knows too well the scramble for kidney drugs, the way they vanish from pharmacy shelves, the maddening logistics of imports when the local supply runs dry.

She still sees Dr. Kalyesubula quarterly. She still worries about infections and relapses. But she is alive and raising her son. She is living.

“The transplant gave me a second chance,” she said. “I think that’s what many people don’t realize — it’s not about being whole again. It’s about having time. A support system, and never losing hope. Saying to death, ‘not today’. And for me, that’s everything.”

Questions to consider:

1. Why do fewer people in the United States die from kidney disease per capita than in the Uganda?

2. What are some ways to prevent kidney disease?

3. Do you think young people need to worry about diabetes?