by Jill Barshay, The Hechinger Report

February 16, 2026

For two decades, New York City’s small high schools stood out as one of the nation’s most ambitious — and controversial — urban education reforms. Now, a long-term study provides a clearer picture of their successes and disappointments.

In the early 2000s, under former Mayor Michael Bloomberg, the city closed dozens of large high schools with high dropout rates in low-income neighborhoods and, with $150 million from the Gates Foundation, replaced them with smaller ones, often located in the same buildings. Admission to more than 120 of the most popular new small schools was determined by lottery, creating the kind of random assignment researchers prize. (That represented the vast majority of the city’s 140 new small schools.) MDRC, a nonprofit research organization, followed four cohorts of students from the classes of 2009 through 2012 for six years after high school. (Disclosure: The MDRC analysis was funded by the Gates and Spencer foundations, which are among the many funders of The Hechinger Report.)

Related: If you liked this story and want more, sign up for Jill Barshay’s free weekly newsletter, Proof Points, about what works in education.

The early gains were substantial. Two-thirds of students entered high school below grade level in reading or math. Yet 76 percent of students admitted to small schools graduated, compared with 68 percent of those who lost the lottery — an 8 percentage point increase. Because more students finished in four years, the schools were cheaper on a per-graduate basis, MDRC found, even though they cost more per student and required more administrators overall.

College enrollment rose sharply as well. Fifty-three percent of small-school students enrolled in postsecondary education after high school, compared with 43 percent of the comparison group — a nearly 10 percentage point difference. Most attended a college within the City University of New York system.

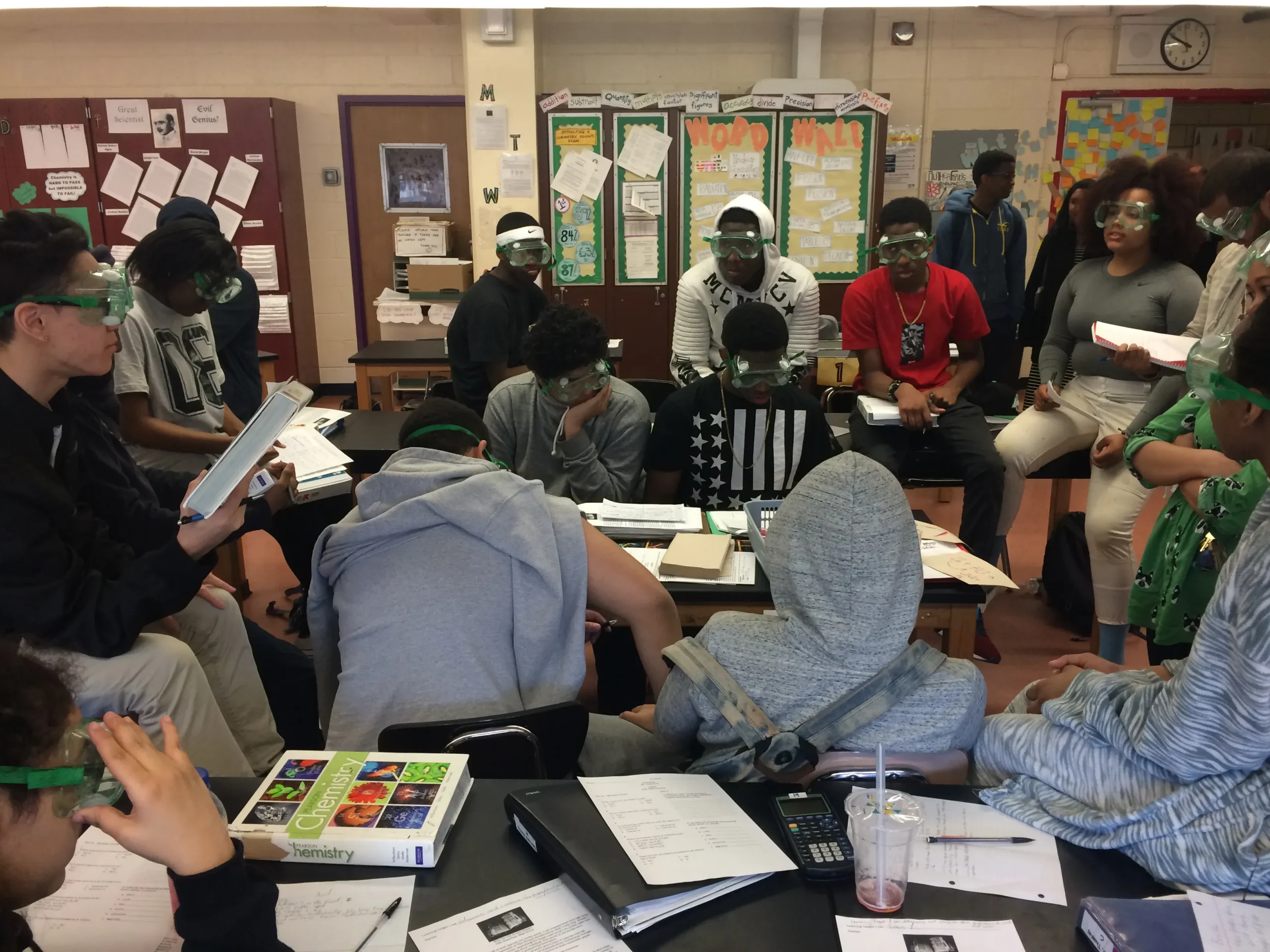

Small schools enrolled roughly 100 students per grade, creating tighter communities where teachers and students were more likely to know one another. Rebecca Unterman, the MDRC researcher who led the study, said the relationships formed in these environments may help explain the graduation and college-going gains. Many schools also built advisory systems in which teachers met regularly with the same students to guide them through academic and emotional challenges and the college process.

The longer-term picture is more sobering.

Although more students enrolled in both four- and two-year colleges, small school alumni did not complete community college in greater numbers than the comparison group. After six years, about 10 percent of students had earned an associate degree, roughly the same share as students who did not attend the small schools. Researchers also found no differences in employment or earnings.

There was one notable exception. Students who enrolled in four-year colleges were more likely to complete a bachelor’s degree if they had attended a small high school. Almost 15 percent of the small-school students earned a four-year degree within six years, compared with 12 percent of their peers.

Joel Klein was the New York City schools chancellor from 2002 to 2011 during the overhaul. Klein said the data shows that the small school effort was worthwhile. He considers it one of his most important accomplishments, along with the expansion of charter schools. Closing large high schools and replacing them with new ones required significant political will, he said, when it sparked resistance from the teachers union. Teachers weren’t guaranteed jobs in the new smaller schools and had to apply again or find another school to hire them.

New York wasn’t the only city to try small schools. Baltimore and Oakland, California, among others, also used Gates Foundation money to experiment with the concept. The results were not encouraging.

Klein argues other cities failed to replicate New York’s success because they simply divided large schools into smaller units without building new cultures. In New York, aspiring principals submitted detailed proposals, just like charter schools, and schools opened gradually, adding one grade at a time.

There were unintended consequences in New York too. During the transition years between the closure of the old school and the slow ramp-up of the new small schools, seats were limited. Enrollments in the remaining large schools in the city rose. While some students enjoyed the intimacy of the new small schools, many more students suffered overcrowding.

Related: Once sold as the solution, small high schools are now on the back burner

Whether because of political resistance, replication challenges or shifting philanthropic priorities, the small-school movement eventually sputtered out. By the 2010s, would-be reformers had shifted their attention toward evaluating teacher effectiveness and school turnaround strategies.

Today, with enrollment declining in many districts, school consolidation, not expansion, dominates the conversation. MDRC’s Unterman said some districts are now exploring whether elements of the small school model — advisory systems or “schools within schools” — can be recreated inside larger campuses.

By all accounts, New York City’s small schools were a vast improvement over the foundering schools they replaced. A majority remain in operation, a testament to their staying power. However, the evidence they leave behind also underscores a hard truth. Improving high school can move important milestones, like getting more students to go to college. Altering students’ economic trajectories may require more radical change.

Contact staff writer Jill Barshay at 212-678-3595, jillbarshay.35 on Signal, or [email protected].

This story about small high schools was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Proof Points and other Hechinger newsletters.

This <a target=”_blank” href=”https://hechingerreport.org/proof-points-small-schools/”>article</a> first appeared on <a target=”_blank” href=”https://hechingerreport.org”>The Hechinger Report</a> and is republished here under a <a target=”_blank” href=”https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/”>Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License</a>.<img src=”https://i0.wp.com/hechingerreport.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/cropped-favicon.jpg?fit=150%2C150&ssl=1″ style=”width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;”>

<img id=”republication-tracker-tool-source” src=”https://hechingerreport.org/?republication-pixel=true&post=114849&ga4=G-03KPHXDF3H” style=”width:1px;height:1px;”><script> PARSELY = { autotrack: false, onload: function() { PARSELY.beacon.trackPageView({ url: “https://hechingerreport.org/proof-points-small-schools/”, urlref: window.location.href }); } } </script> <script id=”parsely-cfg” src=”//cdn.parsely.com/keys/hechingerreport.org/p.js”></script>