Remiah Ward’s shift at the SmartStyle salon inside Walmart was almost over, and she’d barely made $30 in tips from the haircuts she’d done that day. It wasn’t unusual — a year after her graduation from beauty school, tips plus minimum wage weren’t enough to cover her rent.

She scarcely had time to eat and sleep before she had to drive back to the same Walmart in central Florida to stock shelves on the night shift. That job paid $14 an hour, but it meant she sometimes spent 18 hours a day in the same building. She worked six days a week but still struggled to catch up on bills and sleep.

The admissions officer at the American Institute of Beauty, where she enrolled straight out of high school, had sold her on a different dream. She would easily earn enough to pay back the $10,000 she borrowed to attend, she said she was told. Ward had no way of knowing that stylists from her school earn $20,200 a year, on average, four years after graduating. Seven years later, her debt, plus interest, is still unpaid.

In July, Republicans in Congress pushed through policies aimed at ensuring that what happened to Ward wouldn’t happen to other Americans on the government’s dime; colleges whose graduates don’t earn at least as much as someone with a high school diploma will now risk losing access to federal student loans. But one group managed to slip through the cracks — thousands of schools like the American Institute of Beauty were exempt.

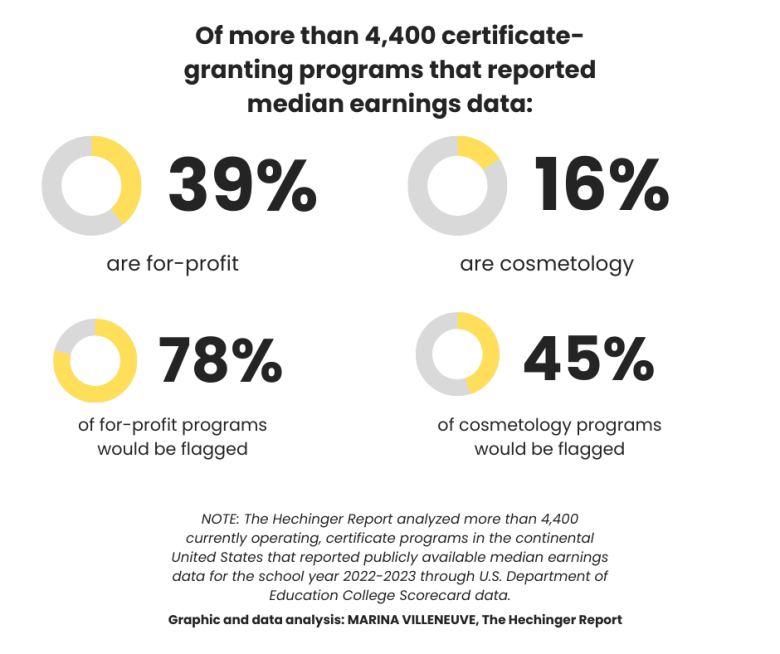

Certificate schools succeeded in getting a carve-out. The industry breathed a collective sigh of relief, and with good reason. At least 1,280 certificate-granting programs, which enrolled more than 220,000 students, would have been at risk of losing federal student loan funding if they had been included in the bill, according to a Hechinger Report analysis of federal data. [See table.] About 80% of those are for-profit programs, and 45 percent are cosmetology schools.

“There is this very strange donut hole in accountability where workforce programs are held accountable, two-year degree programs are held accountable, but everything in between gets off without any accountability,” said Preston Cooper, a senior fellow at the conservative think tank American Enterprise Institute.

The schools spared are known as certificate programs and, with their promise of an affordable and relatively quick path to economic security, are the fastest growing part of higher education. They usually take about a year to complete and train people to be hair-stylists, welders, medical assistants and cooks, among other jobs.

As with traditional colleges, there are big differences in quality among certificate programs. Some hair stylists can make a middle-class living if they work in a busy salon. But for people who have to pay back hefty student loans, the low wages for stylists in the early years can be an insurmountable obstacle.

Ward found herself facing that dilemma. When she could no longer sustain the lack of sleep from her double shifts at Walmart, she pressed pause on her styling career and took a job with Amazon, loading and unloading planes. She wasn’t ready to give up her dream career, though, so in addition to her 10-hour days moving boxes, she took part-time gigs at local hair salons. She didn’t have family to help pay rent, not to mention loan payments, so she couldn’t afford to work fulltime at a salon, which is essential to build up a regular clientele — and bigger tips. Without that, she couldn’t get much beyond minimum wage.

A representative from the American Institute of Beauty denied that Ward was told she would easily repay her loan.

“No admissions representative, not at AIB or elsewhere, would ever make such a statement,” Denise Herman, general counsel and assistant vice president of AIB, said in an email.

The high cost of many for-profit cosmetology schools — tuition can be upward of $20,000, usually for a one-year program — can leave former students mired in debt. In May, the government released data showing 850 colleges where at least a third of borrowers haven’t made a loan payment for 90 days or more, putting them on track to default. About 42 percent of those were for-profit cosmetology and barbering schools (including AIB).

Herman blamed the Biden administration policy that after the pandemic let borrowers forgo payments without any penalty.

“Debtors became ‘comfortable’ not making payments,” said Herman. “AIB provides the graduate with the information graduates need to make their payments. What that graduate decides to pay, or not pay, is not influenced by AIB.”

Under the “big beautiful bill” passed in July, two- and four-year colleges must ensure that, after four years, graduates on average make at least as much as someone in their state who has only a high school diploma. The colleges must inform students if they fail that test, and if it happens for two out of three years, the college will be ineligible to receive federal loan funds.

Some for-profit certificate schools lobbied hard for an exemption. The American Association of Career Schools, which represents proprietary cosmetology schools, spent $120,000 lobbying the Education Department and Congress, including on the “big beautiful bill,” in the first six months of this year. At the group’s major lobbying event in April, Sen. Bill Cassidy, chairman of the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee, was the keynote speaker.

Cassidy declined to answer questions about why certificate programs were excluded, but a fact sheet from his committee noted that they are already covered by something else, the gainful employment rule, which is also being challenged by the for-profit cosmetology industry.

That federal gainful employment regulation, updated in 2023, requires in essence that graduates from career-oriented schools earn enough to be able to pay back their loans and earn more than a high school graduate. It also requires that consumers, like Ward, be given more information about how graduates from all colleges fare in the workplace.

The rule posed an existential threat to a huge swath of cosmetology schools.

In 2023, the American Association of Career Schools sued to block the gainful employment rule.

“AACS supports fair and reasonable accountability measures,” Cecil Kidd, the AACS’s executive director, said in an email. “However, we strongly object to arbitrary or discriminatory policies such as the US Department of Education’s Gainful Employment rule, which unfairly targets career schools while exempting many public and private non-profit institutions that fail to meet comparable outcomes.”

He pointed to public comments in which AACS has argued that the rule imposes an unfair burden on cosmetology schools since stylists are predominantly women, who are more likely to have “personal commitments” that affect their earnings, and who rely on tips that are often pocketed as unreported income.

In a twist that surprised advocates on both sides, the Education Department in May asked the court to effectively dismiss AACS’ lawsuit.

If the court rules in favor of the cosmetology schools, certificate programs will be free of all accountability requirements on their graduates’ earning levels, because they got the carveout in July.

Even if the court rules against cosmetology schools, advocates are pessimistic that the Trump administration will implement the gainful rules. The first Trump administration got rid of the original rules back in 2019 and Nicholas Kent, now the U.S. undersecretary of education, was previously the chief policy officer for Career Education Colleges and Universities, or CECU, the trade group that represents for-profit colleges, including certificate programs. He is a well-known critic of the rule.

“I would be very surprised, if the unlikely scenario plays out that the Biden rule is upheld, that this Department of Education would just say, OK, the court has spoken,” said Jason Altmire, CECU’s executive director. “We are not opposed to accountability for certificate programs, so long as it’s fair to everybody and we have a voice in how you’re measuring programs.”

Altmire said CECU didn’t lobby for certificate programs to be carved out of Congress’ bill, but did argue against the earnings formula that Congress landed on. Altmire said it doesn’t take into account part-time work and the gender gap in wages.

One objection from AACS, raised by CECU as well, is that the earnings measured don’t include tips, which are crucial to hair stylists’ income. Analyzed without including tips, 576 of 724 cosmetology schools in the Hechinger Report analysis would fail Congress’ earnings test. But even if tips were included and raised stylists’ income by 20 percent, 526 cosmetology schools would still fail.

Earlier this year, Remiah Ward made the difficult decision to leave Florida and move to Kentucky, where the cost of living was more forgiving. She’s working from 7 p.m. to 7 a.m. at an aluminum factory for $19.50 an hour.

One day, she might go back to styling after her debt is paid off. Like many former beauty school students, she wishes she’d had more information when she decided to enroll.

“They really sugar-coated it. I was 18 years old, and I needed a trade that I was already pretty good at,” said Ward, who is now 26. “Everybody thinks they’re going to make a high return, and it’s just not the reality.”

Marina Villeneuve contributed data analysis to this story.

This story about cosmetology schools produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger higher-education newsletter.