Under NATO, 32 countries have pledged to defend each other. Is the United States the glue that holds it all together?

Source link

Category: History

-

Decoder Replay: Isn’t all for one and one for all a good thing?

-

The United States as guardian or bully

The recent United States military incursion into Venezuela and abduction and subsequent arrest of its President Nicolás Maduro and his wife in New York is a major geopolitical event. Like all major geopolitical events, it has several components — historical, legal, political and moral.

And like all major geopolitical events, it has very different points of view. There is no grandiose “Truth” about what happened. There are many truths and points of view.

What can be said is that on 3 January 2026, the United States military carried out strikes on Venezuela and captured its president, Nicolás Maduro, and his wife Cilia Flores. The two were then flown to the United States where they were arrested and charged with issues related to narcoterrorism.

The United States’ intervention in a Latin American country has historical precedents as well as current foreign policy implications.

Under President James Monroe, the United States declared in 1823 that it was opposed to any outside colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. Now known as the Monroe Doctrine, it established what political scientists refer to as a “sphere of influence”; No foreign country could establish control of a country in the United States-dominated Western Hemisphere.

(This was indeed one of the central issues in the 13-day October 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis when the United States established a blockade outside Cuba to stop the installation of Soviet missiles on the island.)

The Trump Corollary

In the latest U.S. official security strategy document — National Security Strategy 2025 — the Monroe Doctrine was presented in what has been labelled “The Trump Corollary.” In it, the government said that defending territory and the Western Hemisphere were central tasks of U.S. foreign policy and national interest. The document clearly stated that activities by extra-hemispheric powers would be considered serious threats to U.S. security.

As such, the “Trump Corollary” of the Monroe Doctrine is the justification of the military action in Venezuela based on stopping Russian and Chinese influence in Venezuela. In addition, it can be seen as the justification for the U.S. to acquire Greenland, resume control of the Panama Canal and stop narcotics and illegal migrants coming into the United States from anywhere in the Western Hemisphere.

But the Corollary and Doctrine are mere national strategic statements. Are they legally justified? The U.S. military operation in Venezuela has been highly criticized by international lawyers as well as United Nations officials. The United Nations Charter, of which the United States is a signatory, clearly forbids the use of force by one country against another country except in the case of self-defense and imminent threat.

In an interview with New Yorker magazine reporter Isaac Chotiner on 3 January, Yale Law School Professor Oona Hathaway noted that when the UN Charter was written 80 years ago, it included a critical prohibition on the use of force by states. “States are not allowed to decide on their own that they want to use force against other states,” she told Chotiner. “It was meant to reinforce this relatively new idea at the time that states couldn’t just go to war whenever they wanted to.”

Hathaway said that in the pre-UN Charter world, you could use force if you felt like drug trafficking was hurting you and come up with legal justification that that was the case. “But the whole point of the UN Charter was basically to say, ‘We’re not going to go to war for those reasons anymore’,” she said.

The legality of an ouster

Besides the international legal issue, there is also a domestic legal question about the Venezuelan military action. The 1973 War Powers Act was enacted to limit the power of the U.S. president to use military forces with the approval of the Congress.

It was enacted following the Vietnam War during which the president engaged troops without Congressional approval or a formal declaration of war. The Act clearly requires the president to notify Congress before committing armed forces to military action.

Trump did not consult with members of Congress before and during the military action in Venezuela. The political implications of the Venezuelan strikes and abduction also have international as well as domestic implications. Internationally, there is a dangerous precedent being set.

If the United States asserts its sphere of influence in the Western Hemisphere, what is to stop the Russian Federation from claiming a similar sphere of influence in the Baltic countries of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia as well as Ukraine?

Similarly, what about Chinese influence in the Indo-Pacific region and especially Taiwan? If the United States claims domination in one geographic region, why can’t other powers like Russia and China do the same?

The Westphalian system

Within the United States, there have also been serious reservations about President Trump’s actions. That was to be expected from the opposing Democratic Party. But, several members of Trump’s Republican Party as well as loyal members of his Make America Great Again (MAGA) movement argue that Trump was elected on the slogan “Make America Great Again.” One of the pillars of that movement is a focus on internal problems instead of foreign interventions.

Republican U.S. Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene used to be one of Trump’s staunchest supporters. On 3 January she told interviewer Kristen Walker on the NBC show “Meet the Press” that America First should mean what Trump promised on the campaign trail in 2024.

“So my understanding of America First is strictly for the American people, not for the big donors that donate to big politicians, not for the special interests that constantly roam the halls in Washington and not foreign countries that demand their priorities put first over Americans,” Greene said.

Other criticisms have centered on President Trump’s focus on restoring business in Venezuela for the U.S. oil industry, which has the world’s largest oil reserves. Republican U.S. Representative Thomas Massie warned that “lives of U.S. soldiers are being risked to make those oil companies (not Americans) more profitable.”

Finally, there are moral arguments against the use of force in Venezuela as well as Trump’s threats of the use of force in Colombia, Cuba and elsewhere. There is no question that Venezuelans had suffered under the rule of Maduro; statistics show the rapid decline in the economy as well as a significant democratic deficit.

Fundamental to today’s notion of international order is what’s known as the Westphalian system of the integrity of state sovereignty. The world has seen an order since the end of World War II and the establishment of the United Nations. That order was based on respect for the rule of law. There are other means for states to act against other states, such as sanctions, below military intervention. One country invading another goes against the basis of the Westphalian system.

The Venezuelan strikes and abduction have set a dangerous precedent.

Questions to consider:

1. What is meant by the “Monroe Doctrine”?

2. When is one country considered part of a “sphere of influence” of another country?

3. How do you define “national security”?

-

What role do diplomats play?

“There is a perception that diplomats lead a comfortable life throwing dinner parties in fancy homes. Let me tell you about some of my reality. It has not always been easy. I have moved 13 times and served in seven different countries, five of them hardship posts. My first tour was Mogadishu, Somalia.”

So said Marie Yovanovitch, a veteran U.S. diplomat who was the first witness in a congressional inquiry held to find out whether President Donald Trump abused his power as president by extorting a foreign president into investigating a Trump rival, former Vice President Joe Biden, in the race for the 2020 U.S. elections.

The congressional hearings, only the third in the nation’s 243-year history to target a president for impeachment, have dominated the U.S. political debate for weeks and will continue making headlines for months both in the United States and elsewhere.

It is a case that highlights, among other issues, widespread perceptions that diplomats have cushy jobs and play a lesser role in implementing foreign policy than soldiers.

Yovanovitch, who was recalled from her post as ambassador to Ukraine for reasons that are at the heart of the impeachment proceedings, went on to tell a hushed meeting chamber: “The State Department as a tool of foreign policy often doesn’t get the same attention and respect as the military might of the Pentagon does, but we are — as they say — ‘the pointy end of the spear.’”

“If we lose our edge, the U.S. will inevitably have to use other tools, even more often than it does today. And those other tools are blunter, more expensive and not universally effective.”

Exhibit A is Cuba.

Those tools include military force and economic sanctions, the latter being Trump’s favourite method to try to bend antagonistic governments to his will. The limits of military force are particularly obvious in Afghanistan and Iraq, where American troops have been waging war for 18 and 15 years, respectively.

Exhibit A for the limits of economic sanctions is Cuba, which withstood an American embargo for more than 50 years. More recently, “maximum pressure” to cripple Iran’s economy has yet to persuade the government there to drop its nuclear ambitions, curb its quest for regional supremacy or curb support for groups hostile to the United States and Israel.

The impeachment hearings have brought into focus the interplay between diplomacy and military strength.

According to a parade of witnesses, all of whom except one were professional diplomats or career civil servants, Trump made the release of $391 million in military aid to Ukraine contingent on its president, Volodymyr Zelenski, launching an investigation into Biden and his son Hunter, who worked for a Ukrainian energy company while his father was the point person for Ukraine in the administration of ex-President Barack Obama.

For the past five years, Ukraine has been fighting Russian-backed separatists in a low-intensity war in the east of the country. It needs the American aid, including anti-tank missiles, to keep control of its territory.

According to administration witnesses in the impeachment hearings, Trump had ordered a freeze on the aid — which had been allocated by Congress — as a lever, thus using public funds for personal advantage.

Big military spender

The main conduit for the request for an investigation was President Trump’s personal attorney, Rudy Giuliani, who is a private citizen, rather than the U.S. ambassador to Ukraine, the State Department or the National Security Council.

Giuliani saw Yovanovitch as an obstacle for the aid-for-investigations deal and he spread false rumours about her being a Trump critic. The end result: she received a middle-of-the-night call telling her to leave her post and take the next flight to Washington.

Ivanovitch’s testimony at the impeachment hearing echoed complaints, voiced mostly in private, from foreign service diplomats almost as soon as Trump assumed office. Now, she said, there is “a crisis in the State Department as the policy process is visibly unraveling, leadership vacancies go unfilled and senior and mid-level officers ponder an uncertain future and head for the doors.”

By word and by tweet, Trump has made clear his disdain for the institutions of state, from the State Department to the Central Intelligence Agency, the FBI and the Justice Department. This year, for the third year in a row, the administration is cutting the budget for the State Department while increasing the Pentagon’s.

The United States already spends as much on its military as the next eight countries combined. It tops the list of global arms sellers. U.S. armed forces outnumber the diplomatic service and its major foreign aid agency by a ratio of around 180:1, vastly higher than other Western democracies.

Beyond military solutions

Curiously, the imbalance between the size of the U.S. armed forces and the civilian agencies that make up “soft power” — chiefly the foreign service and the United States Agency for International Development — have long been a matter of concern for military leaders.

Often used in academic discourse, the term “soft power” was coined in the 1980s by Harvard political scientist Joseph Nye. It embraces diplomacy and assistance to foreign countries as well as cultural and exchange programs meant to improve the image of the United States. Hard power, in contrast, includes guns, tanks, war planes and soldiers.

Last year, budget cuts for diplomacy and development so alarmed the military that 151 retired generals and admirals wrote to congressional leaders to plead for greater emphasis on civilian foreign policy and security agencies. “Today’s crises do not have military solutions alone,” the officers’ letter said.

It quoted an observation by General James Mattis, the Trump administration’s first Defense secretary: “America’s got two fundamental powers, the power of intimidation and the power of inspiration.”

Soon after taking office in January 2017, Trump promised “one of the greatest military buildups in military history” and put forward an “America First budget. It is not a soft power budget, it is a hard power budget.”

There were not then, nor are there now, provisions to boost the power of inspiration.

THREE QUESTIONS TO CONSIDER:

1. In what ways are economic sanctions limited?

2. What is “soft power”?

3. How might you use a form of diplomacy to bring them together two people angry at each other?

-

Whatever happened to the New Universities Challenge?

On a grey March morning in 2008, a ministerial stand-in cut the ribbon on a £25 million glass and steel building that was supposed to transform Southend-on-Sea.

Then chief executive of the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE), David Eastwood had been hastily switched in as guest-of-honour to replace then-minister Bill Rammell.

At the funding council, Eastwood had overseen the flow of millions in public money into this seaside town sixty miles east of London. Behind him was the University of Essex’s Gateway Building – six floors of lecture theatres, seminar rooms and local ambition.

The name had been suggested by Julian Abel, a local resident, chosen because it captured both the building’s location in the Thames Gateway regeneration zone and its promise as “a gateway to learning, business and ultimate success.”

Colin Riordan, the university’s vice chancellor, captured the spirit of the moment:

While new buildings are essential to this project, what we are about is changing people’s lives.

Local dignitaries toured the building’s three academic departments – the East 15 Acting School, the School of Entrepreneurship and Business, and the Department of Health and Human Sciences.

They admired the Business Incubation Centre designed to nurture local start-ups. They inspected the GP surgery and the state-of-the-art dental clinic where supervised students from Barts and The London would provide free treatment to locals – already 1,000 patients in just eight weeks.

This wasn’t just a university building. It was the physical manifestation of New Labour’s last great higher education experiment – the idea that you could transform left-behind places by planting universities in them – fixing “cold spots” and “left-behind places” with warm words and big buildings. It was as much economic infrastructure as it was education infrastructure.

Once, Southend had been “a magnet for day trippers”, then a shabby seaside resort, then a town so deprived that it attracted EU funding. Into that landscape dropped a £26.2 million glass box with “amazing views of the Thames Estuary on one side and a derelict Prudential block on the other,” explicitly aiming to revive the town’s flagging economy.

Riordan said the campus would “restore the physical fabric of the town centre” and act as a “magnet” for outsiders, while Eastwood supplied a line about a university being “global, national and local” at the same time – world-class research, national recruitment, local benefit.

Initially, Southend grew beyond the Gateway. East 15 got Clifftown Studios in a converted church, giving the town a theatre and performance space. The Forum – a joint public/university/college library and cultural hub – opened in 2013 as a flagship partnership between Southend Council, Essex and South Essex College, widely lauded as an innovative three-way civic project. For a while, Southend genuinely felt like a university town – at least in the city-centre streets around Elmer Approach.

But now seventeen years later, the University of Essex has announced it will close the Southend campus. The Gateway Building will be emptied, 400 jobs will go, and the town’s dream of becoming “a vibrant university town” may now end with recriminations about financial sustainability and falling international student numbers.

The council leader, Daniel Cowan, says:

…our city remains perfectly placed to play a major national role in higher education, business, and culture.”

But does it?

A gateway of excellence

To understand how Southend’s university dream died, we need to understand how it was born – in the marshlands of Thames Gateway, in the policy papers of Whitehall, and in the peculiar optimism of Britain in the mid-2000s, when anything seemed possible if you just built it.

In the dying days of the John Major years, to the east of London was a mess – dominated by derelict wharves, refineries and marshland – but it was also a potential route for the new Channel Tunnel Rail Link. In 1991, Michael Heseltine told MPs that the new line “could serve as an important catalyst for plans for the regeneration of that corridor” and announced a government-commissioned study into its potential.

The thinking was formalised in 1995, when ministers published the Thames Gateway Planning Framework (RPG9a) – regional planning guidance for a “major regional growth area” extending from Newham and Greenwich in London to Thurrock in Essex and Swale in Kent. It was very much late-Conservative spatial policy – trying to capture South East housing and employment growth in a defined corridor while using new infrastructure and land-use policy to civilise what one background paper called the “largest regeneration opportunity in Western Europe.”

New Labour scaled the whole thing up. In February 2003, John Prescott launched a Sustainable Communities Plan, which “set out a vision for housing and community development over the next 30 years”, with the Thames Gateway as its flagship growth area. Southend became the seaside town that would anchor the estuary’s eastern edge, absorb some of the new housing, and symbolise that this wasn’t just about London’s fringe – but about reviving places that had been left behind by deindustrialisation.

2001’s Thames Gateway South Essex vision even identified Southend’s future role as the cultural and intellectual hub and a “higher education centre of excellence for South Essex.”

In a 2006 Commons adjournment debate on “Southend (Regeneration)”, David Amess stitched the university and college expansions into promises of 13,000 new jobs and thousands of homes by 2021. Accommodating growth at the University of Essex Southend campus and South East Essex College, he argued, was key to turning the town centre into a “cultural hub”, alongside plans for a public and university library and performance and media centre.

By the time John Denham published A New University Challenge: Unlocking Britain’s Talent in March 2008, Southend was the exemplar. In the South Essex case study the prospectus tells a neat story – Essex’s involvement began in 2001 via validated programmes at South East Essex College, evolved into a “distinctive” partnership pulling a research-intensive university into a major widening participation and regeneration project.

With support from HEFCE, central and local government, it aimed to grow student numbers in the town from 700 to 2,000 by 2013 as “the beginning of a vision to make Southend a vibrant university town.”

Regeneration tales

There were plenty more. In “A New University Challenge,” Denham reminded readers that, since 2003, capital funding and additional student numbers had already gone into eleven areas – Barnsley, Cornwall, Cumbria, Darlington, Folkestone, Hastings, Medway, Oldham, Peterborough, Southend and Suffolk – with HEFCE agreeing support for six more – Blackburn, Blackpool, Burnley, Everton, Grimsby, and North and South Devon.

He estimated that around £100 million in capital had been committed so far, with capacity for some 9,000 students when all the projects were fully functioning.

Cornwall was another showcase. The Penryn (then Tremough) campus – developed through the Combined Universities in Cornwall scheme – used EU Objective One money and UK government funding via the South West RDA to build a shared site for Falmouth and Exeter in a county with historically low higher education participation and a fragile, seasonal economy.

Subsequent evidence to Parliament from Cornwall Council was explicit that CUC was designed to deliver economic regeneration as much as access, focusing European investment on “business-facing activity” and experimentation in outreach to firms that had never worked with universities before.

Cumbria got its own mini-origin story. Denham described the new University of Cumbria – launched in 2007 – as “a new kind of institution” with distributed campuses in urban and rural settings – designed to meet diverse learner needs and provide, with partners, the “skills that are essential” to create the workforce that would go on to decommission the Sellafield nuclear power plant.

Later DIUS reporting, REF environment statements and parliamentary evidence on the nuclear workforce all reprise the same themes – Cumbria as an anchor institution, a regional skills engine and a piece of the civil nuclear skills jigsaw.

Suffolk was presented as the archetypal “cold spot.” In 2005 UEA and Essex, backed by Suffolk County Council, Ipswich Borough Council, EEDA and the Learning and Skills Council, secured £15 million from HEFCE to create University Campus Suffolk on Ipswich Waterfront – a county of over half a million people with no university, low participation and significant planned growth.

Denham sold UCS as both a response to education under-supply and an enabler of economic regeneration. Later coverage in The Independent made the same point in more colourful language – Ipswich finally had its own glamorous waterfront campus “full of thousands of students.”

Barnsley, Oldham, Darlington and the like were framed more modestly – university centres in FE colleges that extended HE access to people “who might not otherwise consider participating in higher education.” In Barnsley’s case that meant a town-centre site opened in 2005 by Huddersfield, with investment from HEFCE, Yorkshire Forward and Objective 1 funds, later taken over by Barnsley College but still offering Huddersfield-validated degrees and hosting around 1,600 HE students.

Folkestone, Hastings and Medway were presented as coastal or post-industrial variations on the theme – attempts to use university presence in under-served towns as a driver of creative-quarter regeneration, skills upgrading and image change. University Centre Folkestone, a Canterbury Christ Church/Greenwich joint venture, showed up in coastal regeneration reports as a way to tackle deprivation through improved skills and productivity in South Kent.

The Universities at Medway partnership between Kent, Greenwich, Canterbury Christ Church and Mid-Kent College was talked up in SEEDA case studies as a £50 million dockyard campus replacing thousands of lost shipbuilding jobs and housing over 10,000 students.

All of that was then plugged into the macro-economy story. Denham leaned on work suggesting that a one percentage point increase in the graduate share of the workforce raised productivity by around 0.5 per cent, and argued that higher education contributes over £50 billion a year to the UK economy, supporting 600,000 jobs.

The logic was pretty simple – if you want a more productive, knowledge-intensive economy, you need more graduates in more places – and not just in the big cities.

20 new universities

In March 2008 Denham called the scattered activity the “first wave” – and then announced a competition for the next one:

We believe we need a new ‘university challenge’ to bring the benefits of local higher education provision to bear across the country.

He got his headlines. He asked HEFCE to consult not just institutions but also RDAs, local authorities, business and community groups on how to identify locations and shape proposals. The goals were twofold – “unlocking the potential of towns and people” and “driving economic regeneration.”

HEFCE’s Strategic Development Fund was given £150 million for the 2008–11 spending review. Denham suggested that over six years the fund could support up to twenty more centres or campuses, with commitments in place by 2014 and roughly 10,000 additional student places once mature.

The criteria for bids were revealing about the politics of the moment. Proposals had to demonstrate that they would widen participation, particularly among adults with level 3 who had never considered HE. They had to slot into local economic strategies – supplying high-level skills, supporting business start-ups and innovation, anchoring graduates who might otherwise leave. And they had to show strong HE/FE collaboration, buy-in from councils and RDAs, credible demand modelling, and the ability to manage complex multi-funded capital projects.

HEFCE dutifully ran a two-stage process – statements of intent followed by full business cases. By late 2009, after sifting twenty-three initial bids, the funding council concluded that six were strong enough to develop further, subject to the next spending review. Those six were Somerset (with Bournemouth University), Crawley (Brighton), Milton Keynes (Bedfordshire), Swindon (UWE), Thurrock (Essex) and the Wirral (Chester).

But the initiative wasn’t to last. The 2010 election brought a coalition government that scrapped RDAs, squeezed capital budgets and shifted the English HE settlement onto nine-thousand-ish fees and income-contingent loans. HEFCE’s Strategic Development Fund withered. “Alternative providers” became the policy fashion – and the idea of a central pot funding twenty shiny new public campuses was in the past.

The promised headline – twenty new campuses, twenty new “university towns” – never happened. Instead we got a patchwork of university centres, joint ventures and re-badged FE HE hubs, while national rhetoric shifted from “unlocking towns and people” to “competition and choice.”

Four directions

If we look back now at the original seventeen, we find four basic trajectories.

Barnsley and Oldham have settled into the HE-in-FE pattern. University Campus Barnsley, opened in 2005 by Huddersfield with HEFCE, Yorkshire Forward and Objective 1 support, transferred to Barnsley College in 2013 and now runs as the college’s HE arm, with Huddersfield still validating degrees. University Campus Oldham followed a similar route – opened in 2005 under Huddersfield’s banner and managed by Oldham College since 2012, delivering Huddersfield-validated awards alongside its own.

Cornwall and Medway look closer to what Denham imagined. The Penryn campus now hosts around 6,000 students on a shared Falmouth–Exeter site, with Objective One and SWRDA funding widely credited as crucial to its development.

Universities at Medway, established in 2004 at Chatham Maritime, has struggled – Canterbury Christ Church has all but pulled out, Kent’s numbers are small. The glossy case studies boasting of its £300 million boost to the local economy and its role in remaking a dockyard area that lost 7,000 jobs overnight look less glossy in 2025 – and now, of course, Kent and Greenwich are merging.

Cumbria and Suffolk were the two that ended up as fully fledged universities. The University of Cumbria, established in 2007 from a merger of colleges and satellite campuses, describes itself in REF and internal strategy documents as an “anchor institute” created to catalyse regional prosperity and pride, while continuing to play a role in the nuclear skills ecosystem around Sellafield. University Campus Suffolk secured university title and degree-awarding powers in 2016, with official narrative and sector commentary stressing its success in “transforming the provision of higher education in Suffolk and beyond” – although a significant proportion of its students are franchised.

Grimsby, Blackburn, Blackpool, Burnley, and the Devon centres fall into the “quietly important” category. The £20 million University Centre Grimsby opened in 2011 and now offers a large suite of higher-level programmes in partnership with Hull and through the TEC Partnership’s own degree-awarding powers. Grimsby Institute marketing describes it as a “dedicated home” for HE and one of England’s largest college-based providers. Similar stories play out in Blackburn, Blackpool and Petroc/South Devon – college-based university centres that rarely appear in the national HE debate but matter enormously for local progression and skills.

Folkestone and Hastings show us the fragility of hanging regeneration hopes on small coastal campuses. University Centre Folkestone operated from 2007 to 2013 as a Canterbury Christ Church/Greenwich initiative, featuring in coastal regeneration studies as a way to address deprivation and skills deficits and energise the creative quarter. But by the early 2010s it had wound down its HE offer, with the buildings folded into Folkestone’s broader cultural infrastructure.

Hastings saw an original centre replaced in 2009–10 by the University of Brighton in Hastings as the university’s fifth campus – itself the subject of fierce local protest when Brighton decided in 2016 to close the site and move provision into a partnership “university centre” model with Sussex Coast College.

Peterborough was a late-blooming outlier. The original University Centre Peterborough, developed with Anglia Ruskin, is now joined by ARU Peterborough – a campus opened in 2022 with significant “levelling up” funding and endlessly described by ministers as addressing a higher education cold spot and boosting local productivity. It was, in many ways, Denham’s model revived under a different party label – but few like it are left.

As for the “Universities Challenge” push, in Somerset, Bridgwater & Taunton College developed University Centre Somerset, offering degrees validated by HE partners. In Crawley, what had been imagined as a bid for a campus manifested as higher-level technical and university-level provision in Crawley College and the Sussex & Surrey Institute of Technology.

Milton Keynes’ ambitions funnelled into University Centre/Campus Milton Keynes, now part of the University of Bedfordshire, with periodic political chatter about eventually having a fully fledged MK university. On the Wirral, Wirral Met’s University Centre at Hamilton Campus offers degrees accredited by Chester, Liverpool and UCLan as part of a broader skills and regeneration role. Thurrock saw South Essex College expand its University Centre presence – exactly the sort of FE-based HE model Denham said he wanted.

Elsewhere, Chester has pulled out of Telford. Gloucestershire is winding down Cheltenham. The University College of Football Business (UCFB) no longer operates in Burnley. Man Met sold Crewe to Buckingham. USW is no longer in Newport, UWTSD is closing Lampeter, Durham is out of Stockton, and Cumbria has mothballed Ambleside.

It turns out that on that grey March morning in 2008, David Eastwood was right. To sustain a full-fledged university campus – with all of the spill out benefits often envisaged – you need international students, national recruitment of home students and local students. Immigration policy change has made the first harder. A lack of deliberate student distribution has made the second harder. And closures like Southend’s leave local students like this.

I personally chose Southend due to being a single parent, wanting to build my career in nursing whilst getting that extra time with my little girl.

A new universities challenge

In its “National Conversation on Immigration” in 2018, citizens’ panels for British Future saw real benefits of international students – it called for student migration and university expansion to be used “to boost regional and local growth in under-performing areas,” and for any major expansion of student numbers to be government-led with the explicit aim of spreading the benefits more widely, including via regional quotas on post-study work visas and new institutions in cold spots.

It talked of “a new wave of university building” and said institutions should be located in places that have experienced economic decline, have fewer skilled local jobs, or are social mobility “cold spots” – with criteria including distance from existing universities and socio-economic need. They then give a worked list of ten suggested locations – Barnstaple, Berwick-upon-Tweed, Chesterfield, Derry-Londonderry, Doncaster, Grimsby, Shrewsbury, Southend and Wigan.

But as we’ve covered before, immigration policy – both during expansion and contraction – is almost always place-blind.

The Resolution Foundation’s Ending stagnation A New Economic Strategy for Britain makes a similar point – it rejects making existing campuses ever larger, and instead calls for new ones able to serve cold-spots “like Blackpool and Hartlepool.” It cites evidence that increasing the number of universities in a region – a 10 per cent rise – is associated with around a 0.4 per cent increase in GDP per capita.

This Tony Blair Institute paper from 2012 – surely the inspiration for Starmer’s 66 per cent target speech – calls for new universities in “left-behind regions” as a way to reduce spatial disparities and break intergenerational disadvantage. Chris Whitty’s 2021 report that highlighted the “overlooked” issues in coastal towns suggested shifting medical training to campuses in deprived towns.

And at a Policy Exchange event on the fringe of Conservative Party Conference that year, Michael “Minister for Levelling Up” Gove was asked about the potential for new universities to bring economic benefits to “places like Doncaster and Thanet.” Gove simply said: “I agree.”

The current Labour government’s Post-16 education and skills white paper makes familiar noises about addressing “cold spots in under-served regions.” But there’s no money for new campuses, no Strategic Development Fund, no New University Challenge. Instead, there’s a working group. And around the edges, we’re watching the geographical distribution of higher education shrink.

Without deliberate planning, sustained funding and political will, clustering will continue to cluster. Universities will consolidate in cities where mobile students want to study and where critical mass already exists. The cold spots will get colder.

OfS talks of universities needing “bold and transformative action.” It doesn’t mean transforming places – it means surviving financially. Even mergers save little money unless they lead to campus closures. And campus closures mean communities losing not just current educational provision but future possibility – the chance that their children might stay local and still get a degree, that their town might attract the businesses and cultural institutions that follow universities, that they might be something more than a void on the educational map.

The Robbins expansion of the 1960s worked because it created entire new institutions with sustained funding and genuine autonomy. The polytechnic expansion of the 1970s worked because it built on existing technical colleges with deep local roots. The conversion of polytechnics to universities in 1992 worked because it recognised existing success rather than trying to create it from nothing. But most attempts since to plant universities in cold spots through satellite campuses and partnership arrangements have struggled – because the system stubbornly refuses to pull levers based on place.

Promises of change

Once a university exits stage left, the impacts can be devastating. Despite promises that the merger and rebranding of the university into the University of South Wales in 2013 would not reduce campuses or student numbers, the 32-acre campus in Newport was closed in 2016 – when a largeish slice of arts and media courses moved to the Cardiff Atrium campus.

Student numbers in the city collapsed from around 10,000 in 2010/11 to just 2,600 a decade later – a drop that left the city, in the words of one local councillor, as “a poor man’s Pontypridd” when it comes to higher education.

The campus had been the city’s third highest employer – now the economic contribution of higher education to the local economy has all but evaporated. As one local put it:

There’s a lot of hate for students until they’re gone.

The Southend closure announcement came with promises too. The university would “support students through the transition.” The local council would “explore options for the site.” The MP would “fight for the community.”

Some will point the finger at the university. But we would be very foolish indeed to blame universities for shutting down campuses that they can’t sustain in a market-led model.

Doing so obscures the fundamental question – if universities are as crucial to regional development as everyone claims, why do we leave their geographical distribution to market forces? Why do we build campuses with regeneration money then expect them to survive on student fees? Why are we place-specific with our physical capital but place-blind with our human capital? Why do we keep repeating the same mistakes?

The answer is uncomfortable – because we’ve never really believed in geographical equity in higher education. We’ve played at it, thrown money at it during boom times, made speeches about it. But when times get hard, when choices must be made, the cold spots are always first to lose out.

The 1960s planners who chose Canterbury over Ashford and Colchester over Chelmsford understood that university location was too important to leave to chance. They made deliberate choices about where to invest for the long term. They understood that some places would need permanent subsidy to sustain provision, and they accepted that as the price of geographical equity.

We’ve lost that understanding. We’ve replaced planning with market mechanisms, strategy with initiatives, and long-term thinking with political cycles. Places like Southend are the ones that will pay the price – and sadly, it won’t be the last.

-

A warm rapport with the “world’s coolest dictator”

The answer is not yet in. But since 2023, Bukele has doubled down on his project as the “world’s coolest dictator,” to quote a phrase he once used on his X profile. And he has won some high-profile admirers in the United States.

Bukele has repeatedly renewed his March 2022 state of emergency, which suspended constitutional guarantees and by definition is temporary. It has now been extended 39 times over three continuous years since inception. Bukele’s arrest tally, according to a report by human-rights watchdog Cristosal, is now up to at least 87,000 people — more than the death toll of the country’s 12-year civil war, which ended in 1992.

Bukele, who is still just 44, won re-election last year after sweeping aside term-limit restraints. A constitutional reform, approved by a pliant legislature, now empowers him to seek as many future terms as he wants.

A new kind of leader or more of the same?

Bukele’s embrace of digital public services, bitcoin and his tech-bro demeanor seems to suggest he wants to be thought of as a new, modern kind of leader. For all that, he is still following the path of many old-fashioned Latin American caudillos or strongmen before him.

State surveillance and pressure on human rights groups, corruption watchdogs and journalists have ramped up this year to such an extent that Cristosal has pulled its staff out of the country. Everyone, that is, except Ruth López, its lead anti-corruption investigator, who was arrested in May and is still being held on alleged embezzlement charges.

The Salvadoran Journalists Association has closed its offices too, and will operate from outside the country, following passage of a controversial “foreign agents” law in May which targets the finances of nongovernmental organizations receiving funds from abroad. Bukele’s government accuses many such groups of supporting MS-13. Since April 2023, the independent Salvadoran news outlet El Faro has been legally based in Costa Rica because of what it calls campaigns by the Bukele government to silence its voice.

“Autocrats don’t tolerate alternative narratives,” it said at the time. And still, the Trump administration likes what it sees.

Prisons and deportations

Secretary of State Marco Rubio announced on a February visit to El Salvador that Bukele had agreed to use his CECOT mega-prison to house criminals of any nationality deported from the United States — and even to take in convicted U.S. citizens and legal residents, too.

This proposed offshoring of part of the U.S. incarcerated population would be for a fee, Bukele clarified, that would help fund his own country’s prisons like the CECOT.

The United States then deported more than 200 alleged Venezuelan gang members as well as a group of alleged Salvadoran mareros to El Salvador. The Venezuelans were held at the CECOT until being sent home in a prisoner swap deal for a group of Americans held in Venezuela.

It would be illegal to deport a U.S. citizen for a crime, as Rubio seemed to acknowledge. “We have a constitution,” he observed. That didn’t stop Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem from visiting the CECOT in person and using the social media platform X to threaten “criminal illegal aliens” in the United States with being sent there:

“I toured the CECOT, El Salvador’s Terrorism Confinement Center,” she posted. “President Trump and I have a clear message to criminal illegal aliens: LEAVE NOW. If you do not leave, we will hunt you down, arrest you, and you could end up in this El Salvadoran prison.”

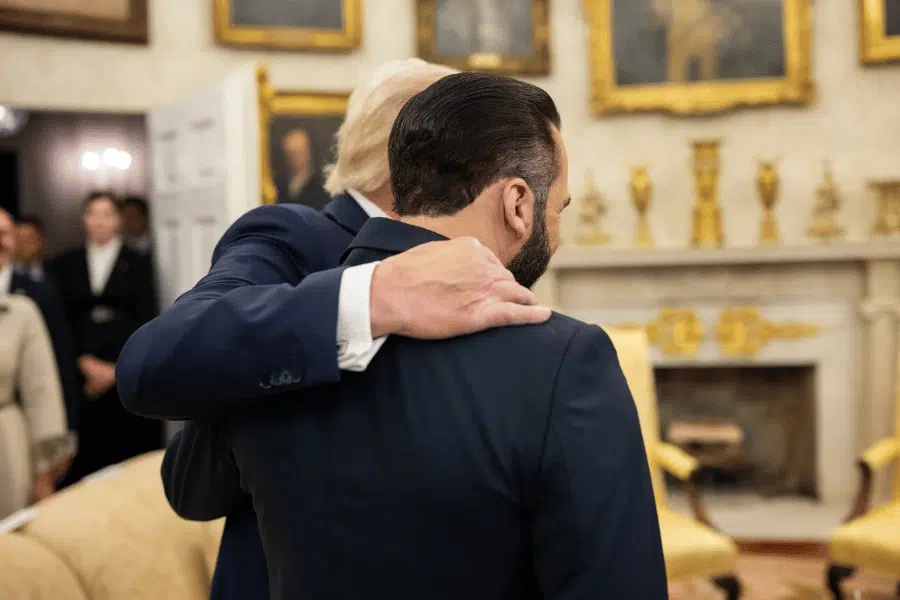

A visit to the White House

Bukele got to make a coveted visit to the White House in April. Trump praised Bukele’s mass imprisonment program, suggesting it could hold U.S. citizens next. Trump was captured telling Bukele on a live feed this: “Home-growns are next. The home-growns. You gotta build about five more places. It’s not big enough.”

The question is, how much of that was just grandstanding?

Like Bukele, Trump has made clear his disdain for constitutional limitations on his power, used government resources to go after his enemies, derided the freedom of the press and talked up domestic security threats to justify heavy-handed, authoritarian policing. The United States has a stronger tradition of democracy than El Salvador, to be sure.

Checks and balances exist. But the strongman playbook does not have too many variations. Ask Viktor Orbán in Hungary or Vladimir Putin in Russia or Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela.

It is not the first time El Salvador has darkly mirrored the fears and internal conflicts of the United States, be they about communism, immigrant crime or democracy. As I wrote in 2023, a straight line can be drawn from the Salvadoran military’s anticommunist violence against impoverished peasants in 1932 to the country’s bloody civil war, in which the United States backed a still atrocity-prone Salvadoran army against leftist rebels.

The line continues from that conflict to the emergence of MS-13, whose presence in the United States drives so much of the Trump administration’s anti-immigrant rhetoric today.

The birth of a global gang

MS-13 members are far from being innocent victims here, though Trump and his supporters have used their crimes to smear immigrants of all kinds. But it’s important to remember that the MS-13 gang, or mara, was formed by young Salvadoran immigrants in Los Angeles. As their home country spiraled toward civil war in the late 1970s, Salvadorans who fled to the United States found themselves threatened by Mexican and other gangs.

What started out as a weed-smoking, heavy-metal listening self-defense clique morphed in time into hardened criminals.

Their power grew when the U.S. government, making a highly visible statement about immigrant crime, deported members of MS-13 and other gangs to El Salvador in the mid 1990s, after the end of the civil war. Within a few years, the gangs ruled the Salvadoran streets. Violence soared in turf wars and government crackdowns. By 2015, gang-related violence made El Salvador the murder capital of the world.

From leading the world’s murder stats, it has now gone to leading the world’s incarceration stats under Bukele. El Salvador’s proportion of the population in prison is now three times that of the United States, which is no slouch when it comes to incarcerating its people (it ranks fifth).

Of course, Salvadorans are entitled to freely elect whomever they want as president, as are U.S. citizens. Both Bukele and Trump won their elections and are doing in office exactly what they said they would do. Yet populist authoritarians have a way of clinging to power and confusing their own needs and egos with the state.

They brook less contradiction and dissent over time. I, for one, hope the increasingly dystopian utopia Bukele is building in his homeland remains just a cautionary tale in El Salvador’s fraught and symbiotic relationship with the United States.

It should not be an inspiration.

Questions to consider:

1. Why might some a majority of people in a country accept rule by a dictator?

2. What is one example of the close relationship between El Salvador and the United States?

3. Do you think that eliminating basic judicial rights can be justified in fighting crime?

-

Where are our young leaders?

Why is it that young leaders are in such short supply?

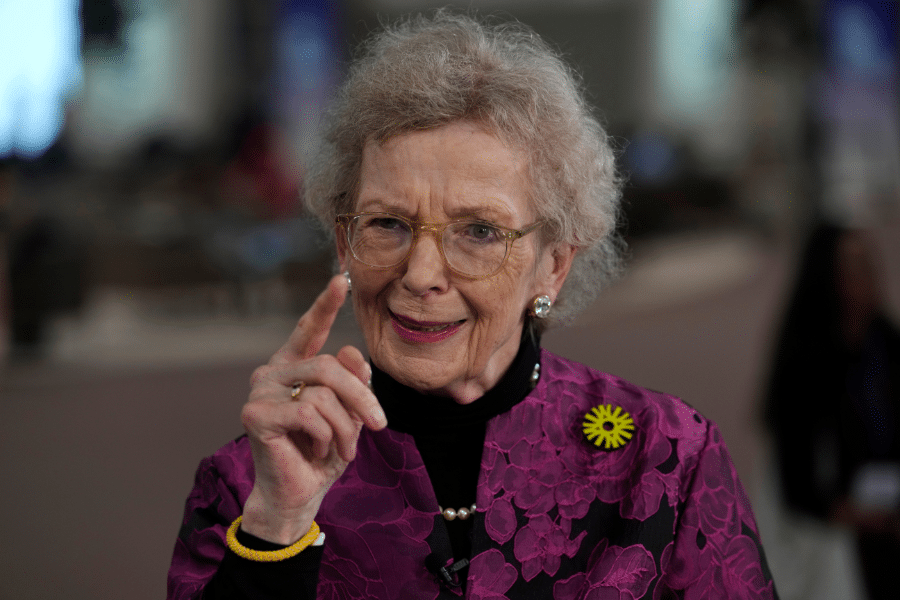

Former Irish President Mary Robinson recently gave one of the most forceful condemnations of Israel’s war on Gaza. Now the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Robinson visited Egypt and the Rafah border and called on states to implement “decisive measures” to halt the genocide and famine in Gaza.

“Governments that are not using all the tools at their disposal to halt the unfolding genocide in Gaza are increasingly complicit,” she said.

Robinson is a member of an organization that calls itself “The Elders.” Founded in 2007 by Nelson Mandela, the South African political prisoner turned president, the group advocates peace, human rights and environmental sustainability.

In her comments, Robinson chided today’s leaders for not fulfilling their legal obligations. “Political leaders have the power and the legal obligation to apply measures to pressure this Israeli government to end its atrocity crimes,” she said.

Robinson is 81 years old. Where are the young leaders making such statements? Where are they organizing groups like The Elders?

Youth power

The media’s attention to Robinson was impressive. Her August press conference was followed by several lengthy interviews on major networks. An independent group like The Elders — whose members include former presidents, UN officials and civil society activists — deserves recognition. It also invites reflection on the role of age in today’s accelerated time.

Being elderly and having once held an important position was not always politically positive. “Don’t trust anyone over 30,” was a popular expression in the 1960s. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was just 26 when he led the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott and 34 when he delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech during the 1963 Washington rally in front of the Lincoln Memorial. John F. Kennedy was 30 when he was elected to the U.S. Congress and 43 when he was elected president. Student leaders made their marks on U.S. politics in the 1960s.

Mario Savio was 21 when he led the Berkeley Free Speech Movement in California, which demonstrated the political power of student protests.

Mark Rudd was a 20-year-old junior when he led strikes and student sit-ins at Columbia University to push for student involvement in university decision making.

Tom Hayden was 20 when he cofounded Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), a national student movement that opposed the Vietnam War and pushed for a complete reform of the political system. At age 22, he wrote the Port Huron Statement, a political manifesto that called for non-violent student activism and widespread civil disobedience achieve the international peace and economic equality that government leaders had failed to achieve.

Savio, Rudd and Hayden were more than just campus activists; they were front page national news.

Age politics

Where are the student leaders opposing Trump’s attack on universities and freedom of expression now? College presidents, professors and boards of trustees are shouldering the burden. There is a generational vacuum.

Youth and youthful dynamism are no longer viewed as political positives. Today, no one could imagine the 79-year-old Donald Trump playing touch football on a beach in Florida as John F. Kennedy and family did at Hyannis Port on Cape Cod when he was president.

In reality, Kennedy suffered from many serious medical conditions but they were largely hidden from the public; it was crucial that he maintain his youthful image. Trump swinging a golf club and riding in a golf cart is not a youthful image; even his awkward swing shows his age.

Nor are the pictures of the members of his Mar-a-Lago crowd youthful; they look like a meeting of grandparents. As slogans reflecting their times, Make America Great Again is far from the New Frontier which called for an end to poverty and investing in technology and science to send humans to the moon.

Robinson visited the Rafah crossing with another member of The Elders, Helen Clark. Clark is 75 years old, the former Prime Minister of New Zealand and United Nations Development Program administrator.

Generational change

Of her visit Clark said that she was horrified to learn from United Nations Sexual and Reproductive Health Agency that the birth rate in Gaza had dropped by over 40% in the first half of 2025, compared to the same period three years ago. “Many new mothers are unable to feed themselves or their newborn babies adequately, and the health system is collapsing,” Clark said. “All of this threatens the very survival of an entire generation.”

Based on her years of experience, Clark wisely talked of generational change.

Age benefits people who, like Robinson and Clark, have held important positions. Because of that experience, members of The Elders take no political risks by speaking out.

The 83-year-old U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders is a notable exception of an elder speaking out in the United States while still in office. For whatever reasons, the elderly members of the Senate — there are currently seven senators who are in their 80s and 17 are in their 70s — have been particularly silent on issues like Gaza.

In fact, they have been particularly silent on most issues.

Where are the Savio/Rudd/Haydens today? A comparable young leader is Greta Thunberg. Greta was only 15 when she initiated the climate strike movement Fridays for Future. But while Greta initiated the movement, she did not organize it as Tom Hayden did with the formation of the SDS. Thunberg is an important symbol and example of courage — the drone attack on her Gaza-bound “Freedom Flotilla” is beyond reprehensible and consistent with Israel’s total war — but she is not a movement organizer on a national or global level.

What makes statements by people like Robinson and Clark so impressive is that they stand out in a realm of stunning silence.

The New Frontier

The Democratic Party in the United States, for example, has no serious leadership. (The same might be said for Socialists in Europe and the Labour Party in Great Britain.) The Democrats inability to rally around 33-year-old Zohran Mamdani who is running for mayor of New York City is an example of the Party’s cowardice and/or lack of vision.

While the older, established Democrats are quick to criticize Trump, they offer no new strategies or actions.

We are desperately waiting for something new. JFK’s motto The New Frontier touched a foundational American embrace of the frontier, the space between the known and new. Back in 1893, historian Frederick Jackson Turner came up with a theory that the continual expansion of the American frontier westward allowed for continual reinvention and rebirth, and that shaped the character of the American people. This frontier theory is essential to an America’s identity built on always moving forward. In contrast, Trump’s return to the past is anti-frontier. MAGA is nostalgia and passé.

Where are today’s young progressives presenting new political possibilities as Hayden and his cohorts did with Port Huron and SDS? Or does asking that question show that I am being too nostalgic about the past as well?

A version of this article was published previously in the magazine Counterpunch.

Questions to consider:

1. Who are “The Elders” and what are they trying to achieve?

2. What was “The New Frontier” and what did it say about the American character?

3. Do you think you would be more likely to vote for some very old over someone very young for political office? Why?

-

Should a society pay for sins of the past?

The Church of England announced in January that it would pledge £100 million to address the past wrongs of its historic links with the colonial-era slave trade.

The acknowledgment by Justin Welby, the Archbishop of Canterbury, that it was “time to take action to address our shameful past” was a sign of a growing focus on reparations for the sufferings of slavery some two centuries after it began to be outlawed.

At issue is the question of whether states, institutions and even individuals, whose predecessors and ancestors profited from trans-Atlantic slavery, owe a debt to the descendants of those who were forced to endure it.

Up to 12 million enslaved Africans are estimated to have been forcibly shipped across the Atlantic from the 16th and 19th centuries by European colonisers.

The now independent countries of the Caribbean and Africa that emerged from the colonial era have long pressed for an apology and restitution from those societies that were enriched by the trade.

Slavery and civil rights

In the United States, those pressuring for reparations to be paid to the descendants of slaves have highlighted the continuing economic and social pressures on many Black Americans, a century and a half after the institution of slavery was formally abolished.

The U.S. debate has led to political controversy over who should receive reparations, with some campaigners in California pressing for potentially life-changing pay-outs to individual descendants of those exploited well into the post-slavery era. In January, Los Angeles County agreed to pay $20 million for a beach that was seized from a Black family in the 1920s and returned to their heirs this summer.

Wider attention to the issue was spurred in part by the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd, an African-American man, by a white police officer in Minneapolis in 2020.

His death galvanised the Black Lives Matter movement and prompted widespread demonstrations that spread from the U.S. to more than 60 countries.

Within weeks of Floyd’s murder, anti-racism protestors in the UK had toppled the statue of Edward Colston, a 17th-century Bristol merchant and slave trader who, until then, was barely known outside his home city. Other monuments to those said to have profited from the trade were also targeted.

One factor in the wider public’s previous ignorance of Colston and others might be that the history of the slave era had traditionally been taught in Britain and elsewhere from the perspective of the positive legacy of white abolitionists such as William Wilberforce, rather than on the perpetrators of slavery.

Restitution now for sins of the past

The issue of reparations — should they be paid and, if so, to whom? — raises important moral and philosophical questions.

Should modern generations pay for the crimes of their ancestors, while others are compensated for wrongs they did not personally suffer? Even the Christian Bible is ambivalent about whether the sins of the father should be visited on the son.

In the midst of the wider theoretical debate, however, some people have already made up their own minds.

This month [Eds: February], the family of BBC correspondent Laura Trevelyan announced they would pay £100,000 in reparations for their ancestors’ ownership of more than 1,000 enslaved Africans on the Caribbean island of Grenada.

They also planned to visit the now independent state of Grenada to issue a public apology.

Trevelyan and her relatives had been unaware of the slavery connection until her cousin, John Dower, uncovered it in 2016 while working on the family’s history.

Can equity be achieved without reparations?

Dower acknowledges the role of George Floyd’s death and the Black Lives Matter campaign in raising the profile of the reparations debate. But he says it was the publication of a database of slaveowners by University College London that led to the revelation of his own family’s connection.

He told News Decoder the world continued to live with the legacy of slavery. Dower is a resident of Brixton, a London neighbourhood that attracted Caribbean immigrants from the 1950s.

“I see the effects of slavery every day of the week in terms of people’s lives and job prospects,” Dower said.

Laura Trevelyan meanwhile acknowledges she is a beneficiary of the activities of her ancestors of which she had previously been unaware. “If anyone had ‘white privilege’, it was surely me, a descendant of Caribbean slave owners,” the London Observer quoted her as saying.

“My own social and professional standing nearly 200 years after the abolition of slavery had to be related to my slave-owning ancestors, who used the profits to accumulate wealth and climb up the social ladder.”

From individual action to a societal response

Dower said he hoped the family’s contribution would act as an example. “We are giving according to our means. And it will be going to educational funding. We are talking about mentorship and knowledge exchange.”

The actions of individuals may indeed put pressure on others linked to the slave trade.

The government of Barbados is reported to have been in touch with the multimillionaire British Conservative MP Richard Drax, whose ancestors were among the prime movers behind the slave-based sugar economy on the Caribbean island.

He still owns a plantation in Barbados as well as the 17th-century Drax Hall that local politicians want to turn into an Afro-centric museum.

Barbados and other states in the Caribbean Community (Caricom) have long been campaigning for the payment of reparations from former colonial powers and the institutions that profited from slavery.

It now seems that individuals might set a trend that politicians and institutions would be obliged to follow.

The reparations debate remains a live one. It raises potentially divisive issues of Black and white identity that already feed the so-called culture wars. In the light of economic turmoil, it can also spur the rhetoric of those who oppose reparations on the grounds that ‘charity begins at home’.

Those arguing for reparations perhaps have one trump card in their hand. One community was indeed compensated when the era of trans-Atlantic slavery ended. It was the slaveowners themselves.

Money that should perhaps have gone to the victims of the slave trade went, instead, to those who had profited from their labours.

Questions to consider:

1. Should modern generations pay for the crimes of ancestors who owned slaves?

2. Should people be compensated for wrongs done to their families long before they were born?

3. If reparations are paid, should they go to individuals; governments; or to institutions that might foster greater inter-community understanding?

-

Is international strife the norm?

A war that couldn’t be stopped

When Russia invaded Ukraine, hopes for action by “the international community” were dashed within days when the UN General Assembly failed to pass a resolution demanding the immediate withdrawal of invasion forces: five countries voted against it and 35 others abstained.

They included two of the five countries that have permanent seats on the UN Security Council. Any of those five countries can veto any joint measure even if the entire rest of the world is in favour.

But even as the UN failed to intervene in the Ukraine conflict in the role of “the international community” as it was perceived by many during the Cold War, a group of countries — led by the United States but including NATO and the European Union — have since supported Ukraine with billions worth of weapons and economic aid.

On an anniversary of the civil war in Syria, meanwhile, the advocacy group Amnesty International blamed “the international community’s catastrophic failure to act” for the war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in that conflict. It was Russian air power that turned the tide of war in favour of President Bashar al-Assad’s government.

Assad might be a pariah in the West. But he was embraced by the Arab League in May. That’s a 22-member organization of nations in North Africa, West Asia and parts of East Africa. It had expelled Syria in 2011 for cracking down on anti-government protestors with a brutality so savage it was shocking even to an organisation with a poor record of concern for human rights.

If the United Nations is powerless because it can’t reach unanimity of its members and if Russia and its allies have different world views than the member nations of NATO and these views differ from the concerns of the members of the Arab League, what “international community” is there?

Democracy battles tyranny.

As for the shared vision for a better world visualized by Annan: is it becoming dimmer or brighter?

There is reason for pessimism. Around the world, democracy is in decline and authoritarian leaders, such as Syria’s Assad and Russia’s Putin, are literally getting away with murder.

Freedom House, a Washington-based non-governmental organisation that keeps track of global freedom and peace, says in its latest report that global freedom has declined for 17 consecutive years.

The United States was once considered a model for others to follow. But Donald Trump, in his four years as president, has encouraged authoritarian leaders. After he lost the presidential election in 2020, he attempted to halt the peaceful transfer of power.

Trump loathed international agreements and pulled the United States out of the International Criminal Court, the UN Human Rights Council, the global compact on migration and the Paris Climate Accords.

Every country in the world has signed the Paris agreement, making it one of the few actions that can be ascribed to the entire international community. Trump’s successor, Joe Biden, signed the paperwork to bring the United States back into the Paris agreement on his first day in office.

Can regional organisations come together?

As far as the more routine use of the phrase is concerned, Richard Haas, long-time president of the New York-based think tank Council on Foreign Relations until he retired in June, once described the dilemma in unusually blunt terms:

“The problem is that no international community exists,” he said. “It would require that there be widespread agreement on what needs to be done and a readiness to do it. Banning the term would mean that people and governments assume a greater responsibility for what takes place in the world.”

In some ways governments are assuming greater responsibility, if not as one giant international bloc than by an alphabet soup of sub-groups. There is the G-7, an informal bloc of wealthy democracies (the United States, Britain, France, Germany, Canada, Italy and Japan). There is the G-20 of 19 countries and the European Union. There is ASEAN, the Association of 10 South East Asian Nations. There is the OAS, the Organization of American States. Finally, there is the African Union which brings together 55 countries across that continent.

In theory, they could work towards agreement on what needs to be done to make the world a safe, secure and prosperous place.

Much of their emphasis tends to be on economic matters, none more than BRICS, an acronym coined by Goldman Sachs banker Jim O’Neill for a grouping of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. Moves are underway to widen that group and turn it into a counterweight to the industrialized West.

Could all those groups, working on parallel tracks, result in a true international community? Perhaps the next generation of politicians and citizen activists will succeed where their elders failed.

Questions to consider:

1. Can you think of a way to replace the phrase “the international community”?

2. Do you consider your own country part of it?

3. Can you think of cases where engaged citizens changed their governments’ policies?

-

When nations go too far

When one nation invades another as Russia did with Ukraine, or when one country attacks civilians and then in retaliation for attacks on its citizenry the other country launches disproportional violence, where does international law come in?

What good is international law if countries continue to violate its basic premises?

Even though going to war violates most international law, international humanitarian law (IHL) is designed to establish parameters for how wars can be fought.

So, paradoxically, while war itself is illegal except for under unusual circumstances such as when a country’s very existence is at stake, international humanitarian law establishes the dos and don’ts of what can be done during violent conflicts. (IHL deals with jus in bello, how wars are fought, not jus in bellum, why countries go to war.)

The basics of international humanitarian law have evolved over time.

The development of proportional response

One of the earliest sets of laws came out of ancient Babylon — which is now Iraq — around 1750 BC. The Hammurabi Code, named after Babylonian King Hammurabi, declared “an eye for an eye,” which was a precursor of the concept of proportional response.

Proportionality means if someone pokes out your eye, you cannot cut off his legs, hands and head and kill all his family and neighbors.

Most modern laws of war date from the U.S. Civil War and the Napoleonic wars in Europe. During the American Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln asked Columbia University legal scholar Franz Lieber to establish a code for conduct for soldiers during war.

At about the same time, after observing a particularly horrendous battle of armies fighting Napoleon, the Swiss Henry Dunant and colleagues founded the International Committee of the Red Cross which lay the groundwork for the Geneva Conventions, which govern how civilians and prisoners of war should be treated.

The basics of modern international humanitarian law can be found in the four Geneva Conventions of 1949 and their Additional Protocol of 1977. The purpose of the Conventions and Protocol is the protection of civilians by distinguishing between combatants and non-combatants and the overall aim of “humanizing” war by assuring the distinction between fighters and civilians.