If you agree to something and put it in writing, shouldn’t you abide by that agreement? Until now, that seemed to be a pretty basic idea.

Agreements at the international level come in the form of treaties. When countries sign treaties they voluntarily agree to follow a given set of rules. The agreements tend to be broad and carefully negotiated. Once signed and ratified, treaties commit countries to obligations.

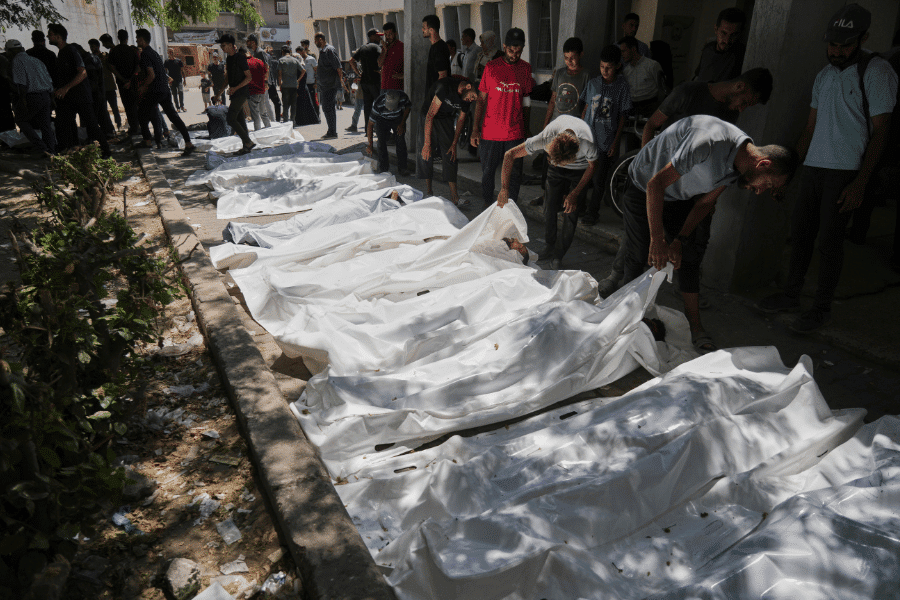

In June, the countries of Finland, Poland, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania announced that they will withdraw from the 1997 Anti-Personnel Mine Treaty. Signed by 165 international states, the treaty forbids the use, production, stockpiling and transfer of anti-personnel landmines, which are devices buried in the ground that explode when someone steps on them.

This month, Ukraine announced it would also withdraw.

Russia’s 2002 invasion of Ukraine radically changed the geopolitical context that existed when the Mine Ban Treaty was signed. But since landmines are only used in times of war, it seems like the potential circumstance of war would have been considered when the countries agreed to ban them.

But Russia, which invaded Ukraine in 2022, never signed the treaty. So has the war in Ukraine really changed everything?

Disarming the power of treaties

All five countries that announced their withdrawal from the treaty border either Russia or Russia-friendly Belarus. The use of anti-personnel landmines can be easily seen as a defensive military action against Russia. Norway, however, which has a 121 mile land border with Russia, remains committed to its anti-mine obligations.

The withdrawals represent a serious weakening of disarmament treaties that have humanitarian objectives as well as respect for international law. The five-country withdrawals could be setting a precedent that could see countries withdraw from other treaties such as those banning biological, chemical and nuclear weapons as well as withdrawals from international institutions.

The withdrawals are a considerable reversal for the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL), a loose coalition of non-governmental organizations that was awarded the 1997 Nobel Peace Prize along with its founding coordinator Jody Williams.

The campaign was an unusual movement that garnered the support of many high profile people, including Princess Diana, Paul McCartney and James Bond actor Daniel Craig.

While treaties are formally signed by states, it is unique that the initiative behind the ICBL came from non-state organizations.

Banning a conventional weapon

Back in 1999, Williams wrote that widespread support for a landmine ban came as a surprise. “Few imagined that the grassroots movement would capture the public imagination and build political pressure to such a degree that, within five years, the international community would come together to negotiate a treaty banning anti-personnel landmines,” she wrote. She noted that it was the first time in history that a conventional weapon in widespread use had been comprehensively prohibited.

That this is no longer the case has shocked land mine opponents.

“We are furious with these countries,” said Thomas Gabelnick, the current director of the ICBL. “They know full well that this will do nothing to help them against Russia.”

The signing of the 1997 Ottawa Convention and the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize were hailed as crucial steps in disarmament – getting governments to reduce their stockpiles of destructive weapons.

The treaty was the first disarmament agreement where governments and civil society worked closely together, representing a new form of international diplomacy. Unlike previous disarmament treaties, it banned weapons actually in use instead of striving to prevent or ban weapons designed as deterrents, such as nuclear weapons – weapons so destructive that the mere fear of their use would stop one country from attacking another.

The treaty ratification process

Historically, the treaty was signed during the euphoric period after the fall of the Berlin Wall and before the 11 September attacks that took down the World Trade Center in 2001. During this period global tensions seemed to be easing. Following the end of the Cold War many believed that more disarmament treaties would follow.

The landmines treaty came into force in 1999 when it was ratified by a sufficient number of states. But some of the most largest and most powerful countries declined to sign. Besides Russia, other countries that stayed out include China, India, Iran, Pakistan, Israel and the United States.

The treaty has successfully led to the destruction of tens of millions of stockpiled landmines. Hundreds of thousands of square miles have been de-mined (13,000 in Ukraine alone) and well the number of civilians maimed or killed by mines has been drastically reduced.

The withdrawal by the five countries could be an unfortunate example for withdrawals from other disarmament treaties or multilateral organizations.

Mary Wareham, the deputy director of the crisis, conflict and arms division at Human Rights Watch, told The New York Times that the withdrawals set a terrible precedent. “Once an idea gets going it picks up steam,” she said. “Where does it stop?”

A treaty set to expire

The last arms control agreement between the United States and Russia, for example, is scheduled to expire in January 2026. Will that treaty — the New Start Treaty — which eliminated important nuclear and conventional missiles, be renewed?

The legitimate reason for leaving a treaty is force majeure, an unforeseen circumstance. As a Finnish Parliamentarian said justifying her country’s leaving the Treaty, the war in Ukraine “changed everything.”

Norway doesn’t agree.

Writing for the European Leadership Network, Wareham and Laura Lodenius, the executive director at Peace Union of Finland, warned that the humanitarian impact will far outweigh any marginal military advantages. “The deterrent factor of re-embracing anti-personnel mines isn’t worth the civilian risk, humanitarian liabilities and reputational damage, all of which extend far beyond their borders,” they wrote.

As for the United States, it has recently withdrawn from bilateral treaties — those between two nations — and several multilateral accords in which multiple parties sign on.

A treaty that ended the Cold War

In a historic ceremony in Iceland back in 1987, U.S. President Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev signed the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF Treaty), which was largely seen as an end to the Cold War that had lasted since the end of World War II.

Under the first Trump Administration in 2019, the U.S. withdrew from that treaty.

Trump has twice withdrawn the United States from the Paris Climate Accord and, in addition, withdrew from the Open Skies Treaty, which allows for the use of surveillance planes or drones for intelligence capturing purposes.

The United States has also withdrawn from institutions like the World Health Organization and is threatening to withdraw from the World Trade Organization. It has already left the U.N. Human Rights Council.

In an ominous move for multilateralism, Trump has set in motion a review of U.S. participation in intergovernmental organizations, including those that are part of the United Nations, with the intention of withdrawing from or seeking to reform them.

Breaking a treaty by executive order

Trump’s executive order of 4 February 2025, started by saying: “The United States helped found the United Nations (UN) after World War II to prevent future global conflicts and promote international peace and security. But some of the UN’s agencies and bodies have drifted from this mission and instead act contrary to the interests of the United States while attacking our allies and propagating anti-Semitism.”

That’s his subjective interpretation of recent events. There is no justification in the mandate for the review for any change based on force majeure, certainly not that the United Nations and some of its agencies “drifted from this mission and instead act contrary to the interests of the United States.”

Withdrawing from treaties or organizations has consequences for global stability. The announcement by the five countries that they are withdrawing from the Mine Ban Treaty is a worrisome addition to Trump’s general assault on multilateralism. Pacta sunt servanda, the underlying principle of contracts and law, translates to “agreements must be kept.” It is the foundation of international law and cooperation.

The withdrawals are a bad omen. They lessen the value of conventions and treaties. States should not respect their obligations only when they are in their favor.

Confidence that states will respect their obligations is the primary support for an international system.

The Ukraine war has not changed that. Without that confidence, the system collapses.

Can we agree on that?

A version of this story has been published previously in the publication Counterpunch.

Questions to consider:

1. What is a treaty?

2. Why would a country decide to not ratify a treaty that bans landmines?

3. When was the last time you agreed to do something. Was it difficult to keep that agreement?