U.S. President Donald Trump views Israel’s war on Gaza through the eyes of the real estate developer he was before he entered politics.

“We have an opportunity to do something that could be phenomenal,” he said at a joint news conference with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu on 4 February. “And I don’t want to be cute. I don’t want to be a wise guy. But the Riviera of the Middle East.”

He was talking about the possibility of forcing 2.2 million Palestinians from Gaza to make place for “the Riviera of the Middle East.”

Elaborating the idea in social media posts and interviews, the U.S. president left no doubt that he saw one of the world’s most complex problems — the Israeli-Palestinian conflict — as a real estate deal.

Trump explained that the United States could take over Gaza, a place where tens of thousands of people have been killed by Israeli air strikes and ground troops over the past 16 months.

Taking ownership of the conflict

Israel has pummelled Gaza ever since 7 October 2024 when gunmen from the militant Hamas group stormed across the border, killed 1,200 Israelis and took more than 250 people hostage.

“I do see a long-term ownership position and I see it bringing great stability to that part of the Middle East and maybe the entire Middle East,” Trump said. “We’re going to take over that piece and we’re going to develop it, create thousands and thousands of jobs. And it will be something that the entire Middle East can be very proud of.”

To make that possible, the people now living in the future Riviera must leave, possibly to neighbouring Jordan or Egypt, he said.

Leaders of both countries have rejected that idea, as has the Arab League, the Secretary General of the United Nations, Antonio Guterres and a host of human rights groups.

Conspicuously absent from statements by Trump and officials of his administration was the matter of international law.

The thorny issue of international law

The forced deportation of civilians is prohibited by an array of provisions of the Geneva Conventions which the United States has ratified.

Forced deportation has been considered a war crime ever since the Nuremberg Trial of Nazi officials.

The International Criminal Court lists the kind of forcible population transfer visualized by Trump’s Riviera of the Middle East plan as both a war crime and a crime against humanity. (The United States is not a member of the court because it never ratified the Rome Statute on the court’s establishment).

The legal and geo-political arguments triggered by Trump’s controversial proposal often leave out the collective trauma that shapes the Palestinians’ national identity and political aspirations.

That trauma dates back to the violence preceding the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948, more than 50 years after an Austrian Jew, Theodor Herzl, published a book (Der Judenstaat) that inspired the Zionist movement.

A history of forced expulsion

An estimated 700,000 Palestinians fled or were expelled from what is now Israel during the war between Zionist paramilitary fighters of the Haganah, the forerunners of today’s Israeli Defence Force, and regular soldiers of six Arab countries.

Palestinians call that forced exodus the Naqba (the catastrophe). At the time, many expected to return to their homes once the fighting was over.

A resolution by the U.N. General Assembly seven months after the formal establishment of Israel provided for a right of return for those who fled. A General Assembly resolution in 1974 declared the right to return an “inalienable right.”

Like all General Assembly resolutions, the 1948 vote was not binding, but it was explicit: “Refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbours should be permitted to do so at the earliest possible date and that compensation should be paid for the property of those choosing not to return…”

Neither happened but the concept that those who left had a right to return has lived on for four generations, with hopes fading gradually but not entirely. There are still families who keep as heirlooms keys to the houses they fled in the turmoil of the Naqba.

How history plays out today

This history helps explain why today’s Palestinians in Gaza take seriously Trump’s proposal to resettle them all and their fear that any resettlement would result in permanent exile.

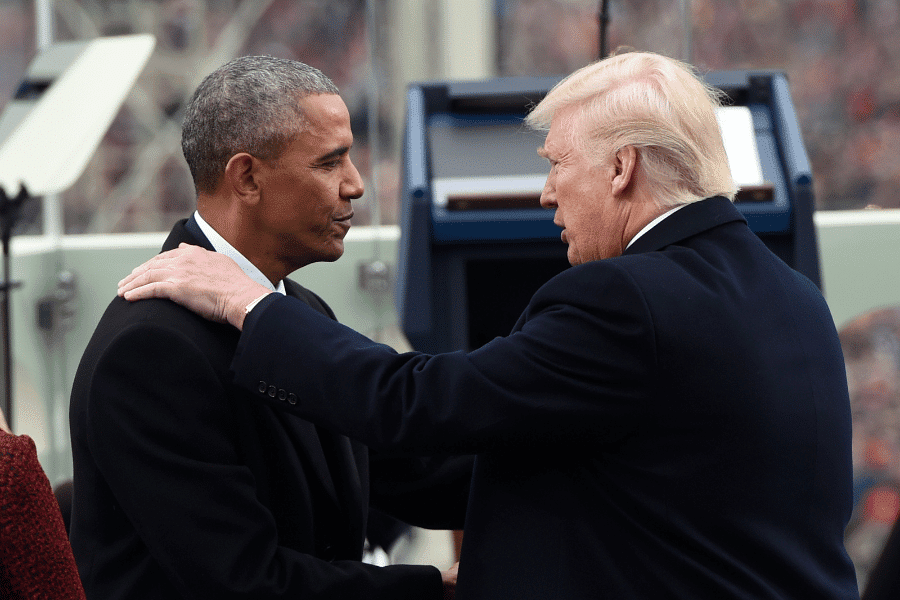

Trump’s “Riviera” proposal came as a surprise, apparently even to Netanyahu who stood next to him at the press conference. But it appears to have been a subject of discussion inside the Trump family for some time.

At an event at Harvard university in February 2024, Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, mused about the untapped value of the Gaza strip and its beautiful beaches. “Gaza’s waterfront property, it could be very valuable, if people would focus on building up livelihoods,” Kushner said.

He did not specify which people would do the building but his father-in-law appears to be determined that it would not be the people now living there.

Who, then? It’s one of many questions yet to be answered in the era of Trump 2.0.

Questions to consider:

• What is one problem Trump will have if he wants the United States to take over Gaza?

• Why do many Palestinians take Trump’s threat of relocation seriously?

• What makes the idea that people have the right to return to homes their ancestors were force out of complicated?