When a little known politician recently declared himself interim president of Venezuela and called for fresh elections, opponents of the sitting president, Nicolás Maduro, saw a bright future for a country mired in misery and hunger.

But ousting Maduro has proved more difficult than expected. Optimistic assumptions have collided with a reality once summed up by the late Chinese leader Mao Zedong: “Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun.”

Juan Guaidó, the youthful opposition figure who declared himself president on January 23, has been recognized as Venezuela’s legitimate leader by the United States and almost 50 other countries. But Maduro is still in power, backed by the country’s military and paramilitary forces. Maduro’s international backers include China, Russia, Turkey, Iran, Cuba, Bolivia and Nicaragua.

What Guaidó and Washington administration officials had in mind sounded optimistic but not impossible.

After Guaidó emerged as undisputed leader of an opposition long weakened by internal feuds, he brought out tens of thousands of demonstrators who denounced a government they blame for an economic collapse that has resulted in severe shortages of basic goods and services.

Humanitarian aid and presidential power

Displays of public anger week after week, or so the thinking went, would convince Maduro to step aside in favor of his 35-year-old challenger. A key test of the dueling presidents’ power — and the military’s ultimate loyalty — hinged on the delivery of humanitarian aid flown in by U.S. military planes in mid-February to the city of Cúcuta on Venezuela’s border with Colombia.

Maduro said the aid was a precursor to a U.S. military invasion, blocked border crossings and dispatched troops to block convoys of trucks or people carrying supplies. In the scenario envisaged by Guaidó, the troops would refuse to intercept desperately needed aid and instead defect en masse.

That did not happen.

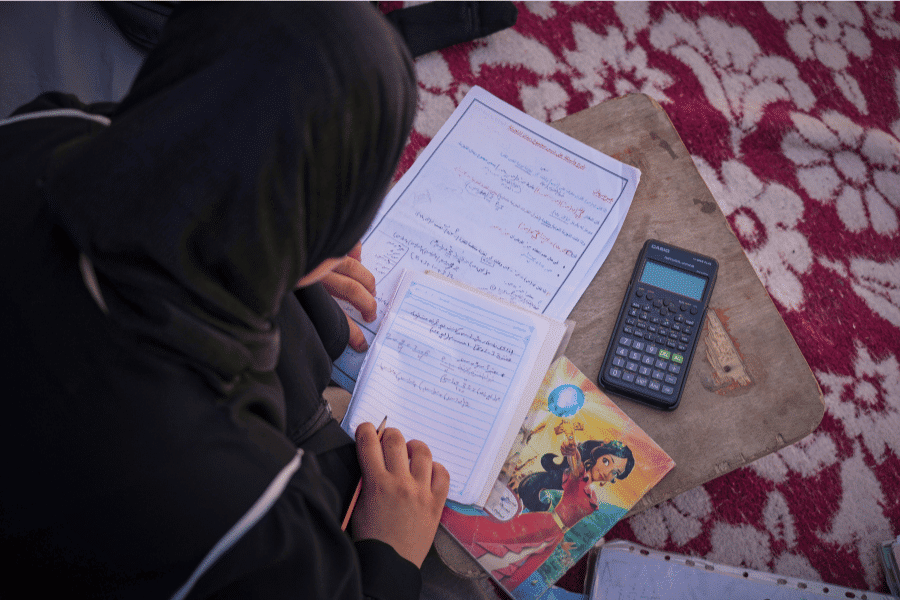

Instead, things have gone from bad to worse since the failed aid delivery. Tons of food, medicine and medical supplies remain boxed in warehouses on the Colombian side of the border.

In March, a week-long power cut across all of Venezuela’s 23 states brought more hardship. With electricity out, scarce food rotted in refrigerators and water pumping stations stopped.

No early end to the suffering

One heart-breaking video showed people rushing to catch water in buckets and plastic bottles from a leak in a drainage pipe feeding into a sewer.

Maduro blamed the blackout on saboteurs using cyber attacks and electromagnetic waves to cripple the power system, operations in an “electric war” waged by the United States.

The opposition pointed to lack of maintenance and an infrastructure that has been crumbling for years.

In the wake of the longest blackout in Venezuela’s history, Guaidó launched a second round of protests, but the crowds have been noticeably thinner than in the early stage of the contest between the rival presidents.

Hopes for an early end of the country’s agony appear to be fading in Venezuela. Not so in Washington, judging from bullish statements by President Donald Trump and his secretary of state, Michael Pompeo. Trump told an enthusiastic crowd of Venezuelan exiles and Cuban-Americans in Miami last month that what he called “the ugly alliance” between the Maduro government and Cuba was coming to a rapid end.

Soon after, Pompeo told a television interviewer he was confident that Maduro’s “days are numbered.”

Bullish statements from Washington

When huge crowds jammed the streets of Caracas and other cities to cheer Guaidó, some U.S. administration officials thought Maduro would soon be on the way out. That he has managed to hang on despite popular anger, international condemnation and painful American sanctions has come as a surprise to many.

Now, the bullish statements from Trump and Pompeo bring to mind American predictions during Barack Obama’s administration concerning Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad when he faced mass demonstrations, international condemnation and U.S. sanctions.

In Syria, peaceful protests morphed into civil war in the summer of 2011, and the Obama team’s point man on the Middle Eastern country described Assad as “a dead man walking.” Eight years later, having prevailed in the war with the help of Russia and Iran, Syria lies in ruins, but Assad looks secure in power.

Shortly before taking office, Trump promised that he would avoid intervention in foreign conflicts and “stop racing to topple foreign regimes.” He has largely stuck to that pledge but is making Venezuela an exception, with repeated assertions that “all options are on the table” — a Washington euphemism for military action.

There’s no single explanation for Trump’s untypical focus on Venezuela. But it is worth noting that he made his toughest speech on the subject in Florida and that he is running for re-election in 2020. Hawkish rhetoric on Venezuela and Cuba plays well with the large Venezuelan-American and Cuban-American communities in that state.

Florida, the country’s third most populous state, is of key importance in presidential elections. It is a so-called swing state that can go to either of the presidential candidates, often by very narrow margins.

QUESTIONS TO CONSIDER:

1. Can you think of a country where a long-entrenched leader recently bowed to the demands of demonstrators?

2. Why do you think China, Russia and several other countries are standing by Maduro?

3. The United States has a history of intervention in Latin America. Can you name some cases?