Key points:

America’s special education system is facing a slow-motion collapse. Nearly 8 million students now receive services under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), but the number of qualified teachers and related service providers continues to shrink. Districts from California to Maine report the same story: unfilled positions, overworked staff, and students missing the services they’re legally entitled to receive.

“The promise of IDEA means little if there’s no one left to deliver it.”

The data tell a clear story. Since 2013, the number of children ages 3–21 served under IDEA has grown from 6.4 million to roughly 7.5 million. Yet the teacher pipeline has moved in the opposite direction. According to Title II reports, teacher-preparation enrollments dropped 6 percent over the last decade and program completions plunged 27 percent. At the same time, nearly half of special educators leave the field within their first five years.

By 2023, 45 percent of public schools were operating without a full teaching staff. Vacancies were most acute in special education. Attrition, burnout, and early retirements outpace new entrants by a wide margin.

Why the traditional model no longer works

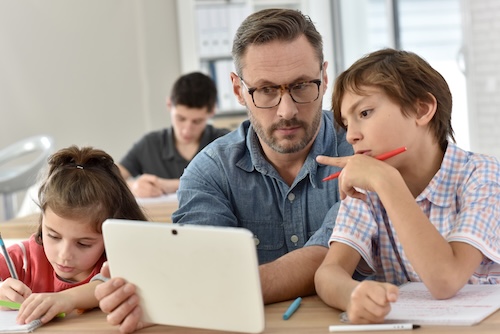

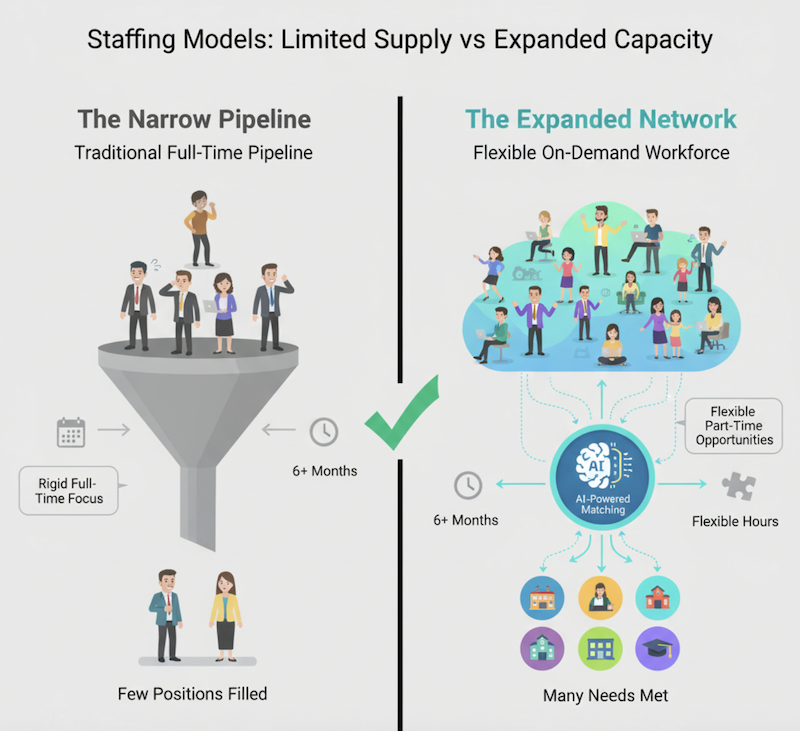

For decades, schools and staffing firms have fought over the same dwindling pool of licensed providers. Recruiting cycles stretch for months, while students wait for evaluations, therapies, or IEP services.

Traditional staffing firms focus on long-term contracts lasting six months or more, which makes sense for stability, but ignores an enormous, untapped workforce: thousands of credentialed professionals who could contribute a few extra hours each week if the system made it easy.

Meanwhile, the process of credentialing, vetting, and matching candidates remains slow and manual, reliant on spreadsheets, email, and recruiters juggling dozens of openings. The result is predictable: delayed assessments, compliance risk, and burned-out staff covering for unfilled roles.

“Districts and recruiters compete for the same people, when they could be expanding the pool instead.”

The hidden workforce hiding in plain sight

Across the country, tens of thousands of licensed professionals–speech-language pathologists, occupational therapists, school psychologists, special educators–are under-employed. Many have stepped back from full-time work to care for families or pursue private practice. Others left the classroom but still want to contribute.

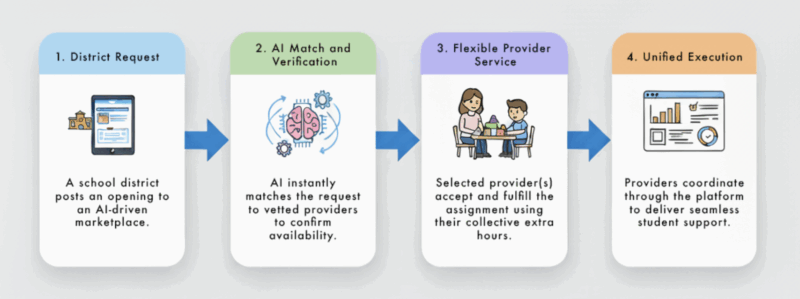

Imagine if districts could tap those “extra hours” through a vetted, AI-powered marketplace. A system that matched real-time school requests with qualified providers in their state. A model like this wouldn’t replace full-time roles; it would expand capacity, reduce burnout, and bring talent back into the system.

This isn’t theoretical. The same “on-demand” concept has already modernized industries from medicine to media. Education is long overdue for the same reinvention.

What modernization looks like

- AI-driven matching: Districts post specific service needs (evaluations, IEP meetings, therapy hours). Licensed providers choose opportunities that fit their schedule.

- Verified credentials and provider profiles: Platforms integrate state licensure databases and background checks to ensure compliance and provide profiles with all candidate information including on-demand, video interviews so schools can make informed hiring decisions immediately.

- Smart staffing metrics: Schools track fill-rates, provider utilization, and service delays in real time.

- Integrated workflows: The system plugs into existing special education management tools. No new learning curve for administrators.

A moment of urgency

The shortage isn’t just inconvenient; it’s systemic. Each unfilled position represents students who lose therapy hours, districts risking due-process complaints, and educators pushed closer to burnout.

With IDEA students now representing nearly 15 percent of all public school enrollment, the nation can’t afford to let a twentieth-century staffing model dictate twenty-first-century outcomes.

We have the technology. We have the workforce. What we need is the will to connect them.

“Modernizing special education staffing isn’t innovation for innovation’s sake, it’s survival.”