Under NATO, 32 countries have pledged to defend each other. Is the United States the glue that holds it all together?

Source link

Category: international relations

-

Decoder Replay: Isn’t all for one and one for all a good thing?

-

The United States as guardian or bully

The recent United States military incursion into Venezuela and abduction and subsequent arrest of its President Nicolás Maduro and his wife in New York is a major geopolitical event. Like all major geopolitical events, it has several components — historical, legal, political and moral.

And like all major geopolitical events, it has very different points of view. There is no grandiose “Truth” about what happened. There are many truths and points of view.

What can be said is that on 3 January 2026, the United States military carried out strikes on Venezuela and captured its president, Nicolás Maduro, and his wife Cilia Flores. The two were then flown to the United States where they were arrested and charged with issues related to narcoterrorism.

The United States’ intervention in a Latin American country has historical precedents as well as current foreign policy implications.

Under President James Monroe, the United States declared in 1823 that it was opposed to any outside colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. Now known as the Monroe Doctrine, it established what political scientists refer to as a “sphere of influence”; No foreign country could establish control of a country in the United States-dominated Western Hemisphere.

(This was indeed one of the central issues in the 13-day October 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis when the United States established a blockade outside Cuba to stop the installation of Soviet missiles on the island.)

The Trump Corollary

In the latest U.S. official security strategy document — National Security Strategy 2025 — the Monroe Doctrine was presented in what has been labelled “The Trump Corollary.” In it, the government said that defending territory and the Western Hemisphere were central tasks of U.S. foreign policy and national interest. The document clearly stated that activities by extra-hemispheric powers would be considered serious threats to U.S. security.

As such, the “Trump Corollary” of the Monroe Doctrine is the justification of the military action in Venezuela based on stopping Russian and Chinese influence in Venezuela. In addition, it can be seen as the justification for the U.S. to acquire Greenland, resume control of the Panama Canal and stop narcotics and illegal migrants coming into the United States from anywhere in the Western Hemisphere.

But the Corollary and Doctrine are mere national strategic statements. Are they legally justified? The U.S. military operation in Venezuela has been highly criticized by international lawyers as well as United Nations officials. The United Nations Charter, of which the United States is a signatory, clearly forbids the use of force by one country against another country except in the case of self-defense and imminent threat.

In an interview with New Yorker magazine reporter Isaac Chotiner on 3 January, Yale Law School Professor Oona Hathaway noted that when the UN Charter was written 80 years ago, it included a critical prohibition on the use of force by states. “States are not allowed to decide on their own that they want to use force against other states,” she told Chotiner. “It was meant to reinforce this relatively new idea at the time that states couldn’t just go to war whenever they wanted to.”

Hathaway said that in the pre-UN Charter world, you could use force if you felt like drug trafficking was hurting you and come up with legal justification that that was the case. “But the whole point of the UN Charter was basically to say, ‘We’re not going to go to war for those reasons anymore’,” she said.

The legality of an ouster

Besides the international legal issue, there is also a domestic legal question about the Venezuelan military action. The 1973 War Powers Act was enacted to limit the power of the U.S. president to use military forces with the approval of the Congress.

It was enacted following the Vietnam War during which the president engaged troops without Congressional approval or a formal declaration of war. The Act clearly requires the president to notify Congress before committing armed forces to military action.

Trump did not consult with members of Congress before and during the military action in Venezuela. The political implications of the Venezuelan strikes and abduction also have international as well as domestic implications. Internationally, there is a dangerous precedent being set.

If the United States asserts its sphere of influence in the Western Hemisphere, what is to stop the Russian Federation from claiming a similar sphere of influence in the Baltic countries of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia as well as Ukraine?

Similarly, what about Chinese influence in the Indo-Pacific region and especially Taiwan? If the United States claims domination in one geographic region, why can’t other powers like Russia and China do the same?

The Westphalian system

Within the United States, there have also been serious reservations about President Trump’s actions. That was to be expected from the opposing Democratic Party. But, several members of Trump’s Republican Party as well as loyal members of his Make America Great Again (MAGA) movement argue that Trump was elected on the slogan “Make America Great Again.” One of the pillars of that movement is a focus on internal problems instead of foreign interventions.

Republican U.S. Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene used to be one of Trump’s staunchest supporters. On 3 January she told interviewer Kristen Walker on the NBC show “Meet the Press” that America First should mean what Trump promised on the campaign trail in 2024.

“So my understanding of America First is strictly for the American people, not for the big donors that donate to big politicians, not for the special interests that constantly roam the halls in Washington and not foreign countries that demand their priorities put first over Americans,” Greene said.

Other criticisms have centered on President Trump’s focus on restoring business in Venezuela for the U.S. oil industry, which has the world’s largest oil reserves. Republican U.S. Representative Thomas Massie warned that “lives of U.S. soldiers are being risked to make those oil companies (not Americans) more profitable.”

Finally, there are moral arguments against the use of force in Venezuela as well as Trump’s threats of the use of force in Colombia, Cuba and elsewhere. There is no question that Venezuelans had suffered under the rule of Maduro; statistics show the rapid decline in the economy as well as a significant democratic deficit.

Fundamental to today’s notion of international order is what’s known as the Westphalian system of the integrity of state sovereignty. The world has seen an order since the end of World War II and the establishment of the United Nations. That order was based on respect for the rule of law. There are other means for states to act against other states, such as sanctions, below military intervention. One country invading another goes against the basis of the Westphalian system.

The Venezuelan strikes and abduction have set a dangerous precedent.

Questions to consider:

1. What is meant by the “Monroe Doctrine”?

2. When is one country considered part of a “sphere of influence” of another country?

3. How do you define “national security”?

-

What role do diplomats play?

“There is a perception that diplomats lead a comfortable life throwing dinner parties in fancy homes. Let me tell you about some of my reality. It has not always been easy. I have moved 13 times and served in seven different countries, five of them hardship posts. My first tour was Mogadishu, Somalia.”

So said Marie Yovanovitch, a veteran U.S. diplomat who was the first witness in a congressional inquiry held to find out whether President Donald Trump abused his power as president by extorting a foreign president into investigating a Trump rival, former Vice President Joe Biden, in the race for the 2020 U.S. elections.

The congressional hearings, only the third in the nation’s 243-year history to target a president for impeachment, have dominated the U.S. political debate for weeks and will continue making headlines for months both in the United States and elsewhere.

It is a case that highlights, among other issues, widespread perceptions that diplomats have cushy jobs and play a lesser role in implementing foreign policy than soldiers.

Yovanovitch, who was recalled from her post as ambassador to Ukraine for reasons that are at the heart of the impeachment proceedings, went on to tell a hushed meeting chamber: “The State Department as a tool of foreign policy often doesn’t get the same attention and respect as the military might of the Pentagon does, but we are — as they say — ‘the pointy end of the spear.’”

“If we lose our edge, the U.S. will inevitably have to use other tools, even more often than it does today. And those other tools are blunter, more expensive and not universally effective.”

Exhibit A is Cuba.

Those tools include military force and economic sanctions, the latter being Trump’s favourite method to try to bend antagonistic governments to his will. The limits of military force are particularly obvious in Afghanistan and Iraq, where American troops have been waging war for 18 and 15 years, respectively.

Exhibit A for the limits of economic sanctions is Cuba, which withstood an American embargo for more than 50 years. More recently, “maximum pressure” to cripple Iran’s economy has yet to persuade the government there to drop its nuclear ambitions, curb its quest for regional supremacy or curb support for groups hostile to the United States and Israel.

The impeachment hearings have brought into focus the interplay between diplomacy and military strength.

According to a parade of witnesses, all of whom except one were professional diplomats or career civil servants, Trump made the release of $391 million in military aid to Ukraine contingent on its president, Volodymyr Zelenski, launching an investigation into Biden and his son Hunter, who worked for a Ukrainian energy company while his father was the point person for Ukraine in the administration of ex-President Barack Obama.

For the past five years, Ukraine has been fighting Russian-backed separatists in a low-intensity war in the east of the country. It needs the American aid, including anti-tank missiles, to keep control of its territory.

According to administration witnesses in the impeachment hearings, Trump had ordered a freeze on the aid — which had been allocated by Congress — as a lever, thus using public funds for personal advantage.

Big military spender

The main conduit for the request for an investigation was President Trump’s personal attorney, Rudy Giuliani, who is a private citizen, rather than the U.S. ambassador to Ukraine, the State Department or the National Security Council.

Giuliani saw Yovanovitch as an obstacle for the aid-for-investigations deal and he spread false rumours about her being a Trump critic. The end result: she received a middle-of-the-night call telling her to leave her post and take the next flight to Washington.

Ivanovitch’s testimony at the impeachment hearing echoed complaints, voiced mostly in private, from foreign service diplomats almost as soon as Trump assumed office. Now, she said, there is “a crisis in the State Department as the policy process is visibly unraveling, leadership vacancies go unfilled and senior and mid-level officers ponder an uncertain future and head for the doors.”

By word and by tweet, Trump has made clear his disdain for the institutions of state, from the State Department to the Central Intelligence Agency, the FBI and the Justice Department. This year, for the third year in a row, the administration is cutting the budget for the State Department while increasing the Pentagon’s.

The United States already spends as much on its military as the next eight countries combined. It tops the list of global arms sellers. U.S. armed forces outnumber the diplomatic service and its major foreign aid agency by a ratio of around 180:1, vastly higher than other Western democracies.

Beyond military solutions

Curiously, the imbalance between the size of the U.S. armed forces and the civilian agencies that make up “soft power” — chiefly the foreign service and the United States Agency for International Development — have long been a matter of concern for military leaders.

Often used in academic discourse, the term “soft power” was coined in the 1980s by Harvard political scientist Joseph Nye. It embraces diplomacy and assistance to foreign countries as well as cultural and exchange programs meant to improve the image of the United States. Hard power, in contrast, includes guns, tanks, war planes and soldiers.

Last year, budget cuts for diplomacy and development so alarmed the military that 151 retired generals and admirals wrote to congressional leaders to plead for greater emphasis on civilian foreign policy and security agencies. “Today’s crises do not have military solutions alone,” the officers’ letter said.

It quoted an observation by General James Mattis, the Trump administration’s first Defense secretary: “America’s got two fundamental powers, the power of intimidation and the power of inspiration.”

Soon after taking office in January 2017, Trump promised “one of the greatest military buildups in military history” and put forward an “America First budget. It is not a soft power budget, it is a hard power budget.”

There were not then, nor are there now, provisions to boost the power of inspiration.

THREE QUESTIONS TO CONSIDER:

1. In what ways are economic sanctions limited?

2. What is “soft power”?

3. How might you use a form of diplomacy to bring them together two people angry at each other?

-

Why so much confusion over climate change?

Bwambale estimates that less than 1% of the global population truly grasps the implications of climate change. “Even worse are Ugandans,” he said.

Gerison pointed out that much of the population of Uganda is young. “With 80% below the age of 25, many haven’t witnessed the full extent of climate changes,” he said.

A diminishing crop is easily understood.

Janet Ndagire, Bwambale’s colleague, said it is difficult for Ugandan natives to connect with climate campaigns. They often perceive them as obstacles to survival rather than crucial interventions.

“Imagine telling someone who relies on charcoal burning for survival that cutting down a tree could be hazardous!” Ndagire said. “It doesn’t make sense to them, especially when the tree is on their plot of land.”

Reflecting on personal experiences, Ndagire recalled childhood days of going to sleep fully covered. Nowadays it is too hot to do that, he said.

Ssiragaba Edison Tubonyintwari, a seasoned bus driver originally from western Uganda but currently driving with the United Nations, recounts the challenges of driving between 5 and 9 AM in the Albertine rift eco-region especially around the Ecuya forest reserve.

“It would be covered in mist,” said Tubonyintwari. “We’d ask two people to stand in front, one on either side of the bus, signalling for you to drive forward, or else, you couldn’t see two metres away. Currently, people drive all day and night!”

Irish potatoes in the African wetlands

What happened? Tubonyintwari pointed to unauthorised tree cutting in the reserve, residential constructions and the cultivation of tea alongside Irish potatoes in the wetlands. The result was rising temperatures.

His account supplements a Global Forest Watch report which puts commodity-driven deforestation above urbanisation.

It’s notable that Tubonyintwari didn’t explicitly use the term “climate change,” yet the sexagenarian can effectively explain the underlying concept through his detailed description of altered environmental conditions.

Global Forest Watch reports alarming deforestation trends, with 5.8 million hectares lost globally in 2022. In Uganda, more than 6,000 deforestation alerts were recorded between 22 and 29 November this year.

The consequences of such environmental degradation are dire. Ndagire emphasised that those who once wielded axes and chainsaws for firewood are now the very individuals facing reduced crop yields due to extreme weather conditions.

Even as Uganda grapples with the aftermath of a sudden surge in heavy rains from last October, Bwambale questions the country’s meteorological department, highlighting the failure to provide precise explanations and climate-aware preparations.

These interconnected narratives emphasise the need for accessible climate campaigns and community-driven solutions. As COP28 gathers elites, the call for a simplified narrative gains prominence, mirroring successful communication models seen during the Covid-19 pandemic; else it’s the same old throwing of good money after bad.

Questions to consider:

1. Why does deforestation continue in places like Uganda when people know about its long-term consequences?

2. In what ways are high level discussions about climate change disconnected from people’s everyday experiences?

3. In what way do you think scientists and environmentalists need to change the climate change narrative?

-

When nations go too far

When one nation invades another as Russia did with Ukraine, or when one country attacks civilians and then in retaliation for attacks on its citizenry the other country launches disproportional violence, where does international law come in?

What good is international law if countries continue to violate its basic premises?

Even though going to war violates most international law, international humanitarian law (IHL) is designed to establish parameters for how wars can be fought.

So, paradoxically, while war itself is illegal except for under unusual circumstances such as when a country’s very existence is at stake, international humanitarian law establishes the dos and don’ts of what can be done during violent conflicts. (IHL deals with jus in bello, how wars are fought, not jus in bellum, why countries go to war.)

The basics of international humanitarian law have evolved over time.

The development of proportional response

One of the earliest sets of laws came out of ancient Babylon — which is now Iraq — around 1750 BC. The Hammurabi Code, named after Babylonian King Hammurabi, declared “an eye for an eye,” which was a precursor of the concept of proportional response.

Proportionality means if someone pokes out your eye, you cannot cut off his legs, hands and head and kill all his family and neighbors.

Most modern laws of war date from the U.S. Civil War and the Napoleonic wars in Europe. During the American Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln asked Columbia University legal scholar Franz Lieber to establish a code for conduct for soldiers during war.

At about the same time, after observing a particularly horrendous battle of armies fighting Napoleon, the Swiss Henry Dunant and colleagues founded the International Committee of the Red Cross which lay the groundwork for the Geneva Conventions, which govern how civilians and prisoners of war should be treated.

The basics of modern international humanitarian law can be found in the four Geneva Conventions of 1949 and their Additional Protocol of 1977. The purpose of the Conventions and Protocol is the protection of civilians by distinguishing between combatants and non-combatants and the overall aim of “humanizing” war by assuring the distinction between fighters and civilians.

-

Are treaties worth the paper they are signed on?

If you agree to something and put it in writing, shouldn’t you abide by that agreement? Until now, that seemed to be a pretty basic idea.

Agreements at the international level come in the form of treaties. When countries sign treaties they voluntarily agree to follow a given set of rules. The agreements tend to be broad and carefully negotiated. Once signed and ratified, treaties commit countries to obligations.

In June, the countries of Finland, Poland, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania announced that they will withdraw from the 1997 Anti-Personnel Mine Treaty. Signed by 165 international states, the treaty forbids the use, production, stockpiling and transfer of anti-personnel landmines, which are devices buried in the ground that explode when someone steps on them.

This month, Ukraine announced it would also withdraw.

Russia’s 2002 invasion of Ukraine radically changed the geopolitical context that existed when the Mine Ban Treaty was signed. But since landmines are only used in times of war, it seems like the potential circumstance of war would have been considered when the countries agreed to ban them.

But Russia, which invaded Ukraine in 2022, never signed the treaty. So has the war in Ukraine really changed everything?

Disarming the power of treaties

All five countries that announced their withdrawal from the treaty border either Russia or Russia-friendly Belarus. The use of anti-personnel landmines can be easily seen as a defensive military action against Russia. Norway, however, which has a 121 mile land border with Russia, remains committed to its anti-mine obligations.

The withdrawals represent a serious weakening of disarmament treaties that have humanitarian objectives as well as respect for international law. The five-country withdrawals could be setting a precedent that could see countries withdraw from other treaties such as those banning biological, chemical and nuclear weapons as well as withdrawals from international institutions.

The withdrawals are a considerable reversal for the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL), a loose coalition of non-governmental organizations that was awarded the 1997 Nobel Peace Prize along with its founding coordinator Jody Williams.

The campaign was an unusual movement that garnered the support of many high profile people, including Princess Diana, Paul McCartney and James Bond actor Daniel Craig.

While treaties are formally signed by states, it is unique that the initiative behind the ICBL came from non-state organizations.

Banning a conventional weapon

Back in 1999, Williams wrote that widespread support for a landmine ban came as a surprise. “Few imagined that the grassroots movement would capture the public imagination and build political pressure to such a degree that, within five years, the international community would come together to negotiate a treaty banning anti-personnel landmines,” she wrote. She noted that it was the first time in history that a conventional weapon in widespread use had been comprehensively prohibited.

That this is no longer the case has shocked land mine opponents.

“We are furious with these countries,” said Thomas Gabelnick, the current director of the ICBL. “They know full well that this will do nothing to help them against Russia.”

The signing of the 1997 Ottawa Convention and the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize were hailed as crucial steps in disarmament – getting governments to reduce their stockpiles of destructive weapons.

The treaty was the first disarmament agreement where governments and civil society worked closely together, representing a new form of international diplomacy. Unlike previous disarmament treaties, it banned weapons actually in use instead of striving to prevent or ban weapons designed as deterrents, such as nuclear weapons – weapons so destructive that the mere fear of their use would stop one country from attacking another.

The treaty ratification process

Historically, the treaty was signed during the euphoric period after the fall of the Berlin Wall and before the 11 September attacks that took down the World Trade Center in 2001. During this period global tensions seemed to be easing. Following the end of the Cold War many believed that more disarmament treaties would follow.

The landmines treaty came into force in 1999 when it was ratified by a sufficient number of states. But some of the most largest and most powerful countries declined to sign. Besides Russia, other countries that stayed out include China, India, Iran, Pakistan, Israel and the United States.

The treaty has successfully led to the destruction of tens of millions of stockpiled landmines. Hundreds of thousands of square miles have been de-mined (13,000 in Ukraine alone) and well the number of civilians maimed or killed by mines has been drastically reduced.

The withdrawal by the five countries could be an unfortunate example for withdrawals from other disarmament treaties or multilateral organizations.

Mary Wareham, the deputy director of the crisis, conflict and arms division at Human Rights Watch, told The New York Times that the withdrawals set a terrible precedent. “Once an idea gets going it picks up steam,” she said. “Where does it stop?”

A treaty set to expire

The last arms control agreement between the United States and Russia, for example, is scheduled to expire in January 2026. Will that treaty — the New Start Treaty — which eliminated important nuclear and conventional missiles, be renewed?

The legitimate reason for leaving a treaty is force majeure, an unforeseen circumstance. As a Finnish Parliamentarian said justifying her country’s leaving the Treaty, the war in Ukraine “changed everything.”

Norway doesn’t agree.

Writing for the European Leadership Network, Wareham and Laura Lodenius, the executive director at Peace Union of Finland, warned that the humanitarian impact will far outweigh any marginal military advantages. “The deterrent factor of re-embracing anti-personnel mines isn’t worth the civilian risk, humanitarian liabilities and reputational damage, all of which extend far beyond their borders,” they wrote.

As for the United States, it has recently withdrawn from bilateral treaties — those between two nations — and several multilateral accords in which multiple parties sign on.

A treaty that ended the Cold War

In a historic ceremony in Iceland back in 1987, U.S. President Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev signed the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF Treaty), which was largely seen as an end to the Cold War that had lasted since the end of World War II.

Under the first Trump Administration in 2019, the U.S. withdrew from that treaty.

Trump has twice withdrawn the United States from the Paris Climate Accord and, in addition, withdrew from the Open Skies Treaty, which allows for the use of surveillance planes or drones for intelligence capturing purposes.

The United States has also withdrawn from institutions like the World Health Organization and is threatening to withdraw from the World Trade Organization. It has already left the U.N. Human Rights Council.

In an ominous move for multilateralism, Trump has set in motion a review of U.S. participation in intergovernmental organizations, including those that are part of the United Nations, with the intention of withdrawing from or seeking to reform them.

Breaking a treaty by executive order

Trump’s executive order of 4 February 2025, started by saying: “The United States helped found the United Nations (UN) after World War II to prevent future global conflicts and promote international peace and security. But some of the UN’s agencies and bodies have drifted from this mission and instead act contrary to the interests of the United States while attacking our allies and propagating anti-Semitism.”

That’s his subjective interpretation of recent events. There is no justification in the mandate for the review for any change based on force majeure, certainly not that the United Nations and some of its agencies “drifted from this mission and instead act contrary to the interests of the United States.”

Withdrawing from treaties or organizations has consequences for global stability. The announcement by the five countries that they are withdrawing from the Mine Ban Treaty is a worrisome addition to Trump’s general assault on multilateralism. Pacta sunt servanda, the underlying principle of contracts and law, translates to “agreements must be kept.” It is the foundation of international law and cooperation.

The withdrawals are a bad omen. They lessen the value of conventions and treaties. States should not respect their obligations only when they are in their favor.

Confidence that states will respect their obligations is the primary support for an international system.

The Ukraine war has not changed that. Without that confidence, the system collapses.

Can we agree on that?

A version of this story has been published previously in the publication Counterpunch.

Questions to consider:

1. What is a treaty?

2. Why would a country decide to not ratify a treaty that bans landmines?

3. When was the last time you agreed to do something. Was it difficult to keep that agreement?

-

Is peace in the Middle East even possible?

The State of Israel was created in 1948. The key word is created. While countries come into being in many different ways, such as violence, revolutions and treaties, the creation of the state of Israel was unique and has proven highly controversial.

To understand the chaos that is now taking place in Israel and the Palestinian territories, one needs to return to that original creation.

The British government ruled the territory known as Palestine under the League of Nations from 1922 until 1948. Already in 1917, the British government issued what is known as the Balfour Declaration which envisioned a Jewish state in what had been claimed a historic Jewish homeland.

Jewish organisations had argued that the land called Israel has been the religious and spiritual center for Jews for thousands of years. While many countries recognized the new State of Israel in 1948, its creation did not effectively redress the dislocation of those who had been living on the territory that Israelis would inhabit.

Following the end of World War II, European Jews who had been displaced during the Holocaust flocked to Israel. The United Nations divided the land into two states, one Jewish, one Arab, which further divided the Arab territory into three sections — the Golan Heights at the Syrian border, the West Bank at the Jordanian border and the Gaza Strip at the Egyptian border.

The creation of deep divisions

The division gave more than 50% of the land to Israel, leaving the Arabs with 42% even though they made up two-thirds of the population.

This resulted in massive Arab displacement and is why the Jewish Independence Day of May 14 is followed by the marking of Nakba Day by Arabs, translated as “The Catastrophe”.

Since Israel’s founding in 1948, there have been several outbreaks of violence between Israel and its neighbors. Among them were the 1948–49 War of Israeli Independence; 1956 Suez Canal Crisis; 1967 Six-Day War; 1973 Yom Kippur War; 1982 Lebanon War and various large-scale Palestinian uprisings known as Intifadas.

None of these conflicts resulted in reparations for the hundreds of thousands of Arabs displaced by Israel’s creation, many of whom ended up in crowded refugee camps in Gaza, the West Bank and neighboring countries.

Further inflaming tensions, Israeli settlers have continued establishing communities in the West Bank, which was conquered by Israel in the 1967 Six-Day War. The international community considers these colonies illegal, and some of the settlers have been found guilty of violence against the Arabs who live there.

Working towards peace

There have been several attempts to have peace agreements between Israel and its neighbors.

The most important are the Camp David Accords of 1978 which was finally reduced to simple diplomatic relations between Egypt and Israel, and the 1993 Oslo accords which established formal relations between Israel and the Palestinian leadership, giving the latter self-governance over the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. Recently, there were talks about a larger regional agreement including Saudi Arabia.

Then came 7 October 2023, when Hamas, an Islamist militant group, attacked Israeli settlers killing more than a thousand people, many of them women and children, and taking over 200 Israeli hostages.

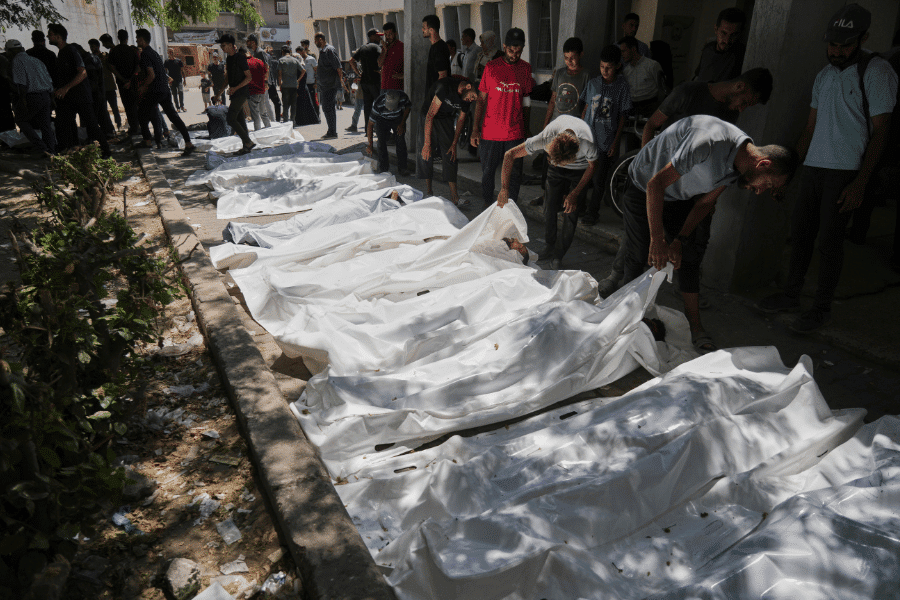

Israel’s response to the Hamas attack, which it justified as legitimate self-defense, has seen more than 32,000 Gazans killed with over 70,000 wounded, mostly civilians with many elderly and children. Much of Gaza’s infrastructure has been destroyed, including hospitals and humanitarian aid has been blocked. Fighting has continued for more than six months as Israel seeks to destroy Hamas and at the same time free the hostages.

The emotions behind the conflict are extreme. The Israelis condemn Hamas as a terrorist organisation whom they argue are out to kill all Jews and destroy the State of Israel. Hamas, which was the official ruling organisation in the Gaza Strip, maintains that Palestinians have been reduced to living in an open-air prison since it took control of Gaza in 2005 when Israel disengaged.

Israel and the international community

The fighting in Gaza has raised many questions relevant to international humanitarian law. South Africa brought a case before the International Court of Justice in The Hague accusing Israel of genocide. The Court ruled that there was “plausible” genocide and ordered several provisional measures Israel must follow, among them increasing access to humanitarian aid.

Beyond Israel, Hamas and the International Court of Justice, various resolutions have been proposed before the United Nations Security Council concerning a ceasefire. Although the latest resolution did pass, with the United States abstaining and not using its veto power, no ceasefire has taken place, although increased humanitarian aid is now entering Gaza.

But the situation of the Palestinians remaining in Gaza remains precarious at best.

The Israel/Hamas conflict has spread to other countries in the region, including Iran, which has long been a supporter of Hamas. On 1 April 2024, Israeli warplanes destroyed a building in Damascus, Syria, part of an Iranian Embassy complex, killing several Iranian officers involved in covert actions in the Middle East.

Shortly after, Iran sent hundreds of drones and cruise missiles towards Israel, which were largely intercepted by Israeli and U.S. air defenses. Subsequently, several drones were downed by Iran’s air defense system near Isfahan, but it is not clear whether they came from Israel or other sources.

What is clear is that there has been enormous international pressure to de-escalate the current situation in order to stop the Israel/Hamas conflict from growing into a regional conflict involving Iran and other countries, or even a more global escalation of violence.

Questions to consider:

1. How did the United Nations divide Palestine to create the state of Israel?

2. What happened to the people displaced in 1948 when Isreal was created?

3. What kind of compromises do you think might have to take place for there to be peace between Israelis and Palestinians?

-

The war in Gaza is a test for humanity

“There will be no electricity, no food, no water, no fuel,” Gallant said. “Everything is closed. We are fighting human animals and we are acting accordingly.”

President Isaac Herzog said militants and civilians in Gaza would be treated alike. “It’s an entire nation out there that is responsible,” Herzog said. “This rhetoric about civilians not aware, not involved — it’s absolutely not true … and we will fight until we break their backbone.”

Netanyahu has been equally explicit, comparing Hamas to “Amalek”, a tribe in the Bible which the Israelites were told to eradicate. He blames Hamas for all civilian casualties.

Other ministers have urged Gaza’s total destruction — one proposed dropping a nuclear bomb — and expulsion of its people, as in the 1948 “Nakba” when several hundred thousand Palestinians were ethnically cleansed as part of Israel’s independence war.

International justice

Whether Israel’s Gaza onslaught amounts to genocide, war crimes or crimes against humanity, or very possibly all three, is for international courts to decide.

What matters now is stopping the killing in a ruined land that has lost its schools, homes, hospitals, roads, power and water plants, farms, places of worship and historical heritage. That is a moral issue for all of us, and most pertinently for Israel and its Western allies, principally the United States, which supplies most of the weapons used against Gaza.

U.S. complicity is beyond doubt. Many European and other countries, by their silence in face of the carnage, or their failure to take action, are also to blame.

Leaders in some of these nations are only now chiding Israel more strongly. Spain’s prime minister has called it a genocidal state. There is talk in European and other capitals of sanctions targeting Israeli leaders, a ban on arms shipments or trade penalties.

But no measures likely to push Netanyahu to alter course have been adopted. His eyes are fixed on the United States, the only nation that could swiftly halt the Gaza debacle — by halting or suspending the $3.8 billion it gives Israel each year in mostly military aid, along with extra arms shipments worth billions of dollars since the current war began.

Quantifying the horror

Cold statistics mask the individual suffering of Gazans, but tell part of the story.

More than 54,000 people, including more than 16,000 children, have been killed since the war began, according to Gaza Health Ministry figures considered reliable by the United Nations, or 2.5% of the population — equivalent to 8.5 million Americans.

This number does not count many thousands whose bodies may still lie under the rubble, or who died weakened by hunger, preventable diseases and failing health care. It includes more than 1,400 health workers and more than 200 journalists and media workers.

United Nations officials say more than 90% of homes have been destroyed or damaged, along with 94% of Gaza’s 36 hospitals, with only some still struggling to function. Gaza has the world’s highest number of child amputees per capita.

According to Hans Laerke, spokesman for the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, Gaza is also the only territory in the world where “100% of the population is threatened with famine” despite Israel’s denial of any humanitarian blockade.

Abetting a genocide

The horrors endured by Palestinians have been documented by local journalists (Israel has banned all international reporters from Gaza), U.N. officials, Palestinian and foreign doctors and aid workers, as well as locally shot videos and photos.

Foreign physicians with long experience of many countries ravaged by war say conditions they witnessed in Gaza are worse than anything they have ever encountered.

“I have worked in conflict zones from Afghanistan to Ukraine,” said U.S. paediatrician Seema Jilani, after an assignment in the southern city of Rafah for the International Rescue Committee. “But nothing could have prepared me for a Gaza emergency room.”

No one can plausibly claim “we did not know” what was, and is, going on.

Yet world powers have largely stood by as massacres unfold in Gaza. They have kept equally silent as Israel batters parts of Lebanon at will despite a ceasefire with Hezbollah militants agreed in November. Israel has also grabbed more land in Syria and bombed hundreds of targets there since Bashar al-Assad’s regime fell in December.

A diplomatic debacle

U.S. President Donald Trump, like President Joe Biden before him, has backed Israel to the hilt. Not even images of emaciated children in Gaza have prompted a change of heart.

Trump’s own contempt for international law and his plan for the removal of Gazans to allow for a fantasy reconstruction on the toxic ruins of their land has only emboldened far-right Israeli leaders with ambitions to “purify”, annex and resettle Gaza, and to do likewise in the West Bank, where half a million Israeli settlers already live.

Israel’s actions, under permissive Western eyes, are shredding a longstanding international consensus on a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict – an idea incompatible with an ever-expanding Israeli grip on the West Bank and Gaza.

After French President Emmanuel Macron called for recognition of a Palestinian state, Defence Minister Israel Katz responded with brutal clarity.

“They will recognise a Palestinian state on paper — and we will build the Jewish-Israeli state on the ground,” he said in the West Bank on May 29 at one of 22 new settlements just approved by the Israeli government.

Can peace be given a chance?

Western outrage at Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has no echo when it comes to Israel which for decades has defied U.N. resolutions and violated international law.

The fate of Gaza may prove a final blow to the rules of international conduct and treatment of civilians agreed after the Second World War — a system already frayed by the Cold War and more recently the illegal U.S.-British invasion of Iraq in 2003.

Crushing the Palestinian people will not make Israel any safer in the long run. Only a true peace settlement on a basis of mutual respect and equality can do that.

If Western nations ever get around to imposing sanctions on Israel and its leaders, they should do so to promote the Jewish state’s real interests which they claim to have at heart — as a stepping stone to such a peace between human beings.

The German-born Jewish-American philosopher and political scientist Hannah Arendt foretold the consequences for a society unable to perceive others as human.

“The death of human empathy is one of the earliest and most telling signs of a culture about to fall into barbarism,” she wrote.

Questions to consider:

1. Is it justified, or wise, for a state to take revenge on its enemies?

2. Do people everywhere have the right to resist occupation?

3. How should we react when a possible genocide is taking place?

-

A history lesson on Europe for Donald Trump

“The European Union was formed in order to screw the United States, that’s the purpose of it.” So said U.S. President Donald Trump in February. He repeats this assertion whenever U.S.-European relations are a topic of debate.

Trump voiced his distorted view of the EU in his first term in office and picked it up again in the first three months of his second term, which began on January 20 and featured the start of a U.S. tariff war which up-ended international trade and shook an alliance dating back to the end of World War II.

What or who gave the U.S. president the idea that the EU was “formed to screw” the United States is something of a mystery. If he were a student in a history class, his professor would give him an F.

Trump’s claim does injustice to an institution that won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2012 in recognition for having, over six decades, “contributed to the advancement of peace and reconciliation, democracy and human rights in Europe” as the Nobel committee put it.

So, here is a brief guide to the creation of the EU, now the world’s largest trading bloc with a combined population of 448 million people, and the events that preceded its formal creation in 1952.

Next time you talk to Trump, feel free to brief him on it.

Staving off war

With Germans still clearing the ruins of the world war Adolf Hitler had started in 1939, far-sighted statesmen began thinking of ways to prevent a repeat of a conflict that killed 85 million people.

The foundation of what became a 28-country bloc lay in the reconciliation between France and Germany.

In his speech announcing the Nobel Prize, the chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, Thorbjorn Jagland, singled out then French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman for presenting a plan to form a coal and steel community with Germany despite the long animosity between the two nations; in the space of 70 years, France and Germany had waged three wars against each other. That was in May 1950.

As the Nobel chairman put it, the Schuman plan “laid the very foundation for European integration.”

He added: “The reconciliation between Germany and France is probably the most dramatic example in history to show that war and conflict can be turned so rapidly into peace and cooperation.”

From enemies into partners

In years of negotiations, the coal and steel community, known as Montanunion in Germany, grew from two — France and Germany — to six with the addition of Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg. The union was formalized with a treaty in Paris in 1951 and came into existence a year later.

The coal and steel community was the first step on a long road towards European integration. It was encouraged by the United States through a comprehensive and costly programme to rebuild war-shattered Europe.

Known as the Marshall Plan, named after U.S. Secretary of State George C. Marshall, the programme provided $12 billion (the equivalent of more than $150 billion today) for the rebuilding of Western Europe. It was part of President Harry Truman’s policy of boosting democratic and capitalist economies in the devastated region.

From the six-nation beginning, the process of European integration steadily gained momentum through successive treaties and expansions. Milestones included the creation of the European Economic Community and European Atomic Energy Community.

In 1986, the Single European Act paved the way to an internal market without trade barriers, an aim achieved in 1992. Seven years later, integration tightened with the adoption of a common currency, the Euro. Used by 20 of the 27 member states, it accounts for about 20% of all international transactions.

Brexiting out

One nation that held out against the Euro was the United Kingdom. It would later withdraw from the EU entirely after the 2016 “Brexit” referendum led by politicians who claimed that rules made by the EU could infringe on British sovereignty.

Many economists at the time described Brexit as a self-inflicted wound and opinion polls now show that the majority of Britons regret having left the union.

In decades of often arduous, detail-driven negotiations on European integration, including visa-free movement from one country to the other, no U.S. president ever saw the EU as a “foe” bent on “screwing” America. That is, until Donald Trump first won office in 2017 and then again in 2024.

What bothers him is a trade imbalance; the EU sells more to the United States than the other way around; he has been particularly vocal about German cars imported into the United States.

Early in his first term, the Wall Street Journal quoted him as complaining that “when you walk down Fifth Avenue (in New York), everybody has a Mercedes-Benz parked in front of his house. How many Chevrolets do you see in Germany? Not many, maybe none, you don’t see anything at all over there. It’s a one-way street.”

This appears to be one of the reasons why Trump imposed a 25% tariff, or import duty, on foreign cars when he declared a global tariff war on April 2.

His tariff decisions, implemented by Executive Order rather than legislation, caused deep dismay around the world and upended not only trade relations but also cast doubt on the durability of what is usually termed the rules-based international order.

That refers to the rules and alliances set up, and long promoted by the United States. For a concise assessment of the state of this system, listen to the highest-ranking official of the European Union: “The West as we knew it no longer exists.”

So said Ursula von der Leyen, president of the Brussels-based European Commission, the main executive body of the EU. Its top diplomat, Kaja Kallas, a former Prime Minister of Estonia, was even blunter: “The free world needs a new leader.”

Questions to consider:

1. Why was the European Union formed in the first place?

2. How can trade serve to keep the peace?

3. In what ways do nations benefit by partnering with other countries?