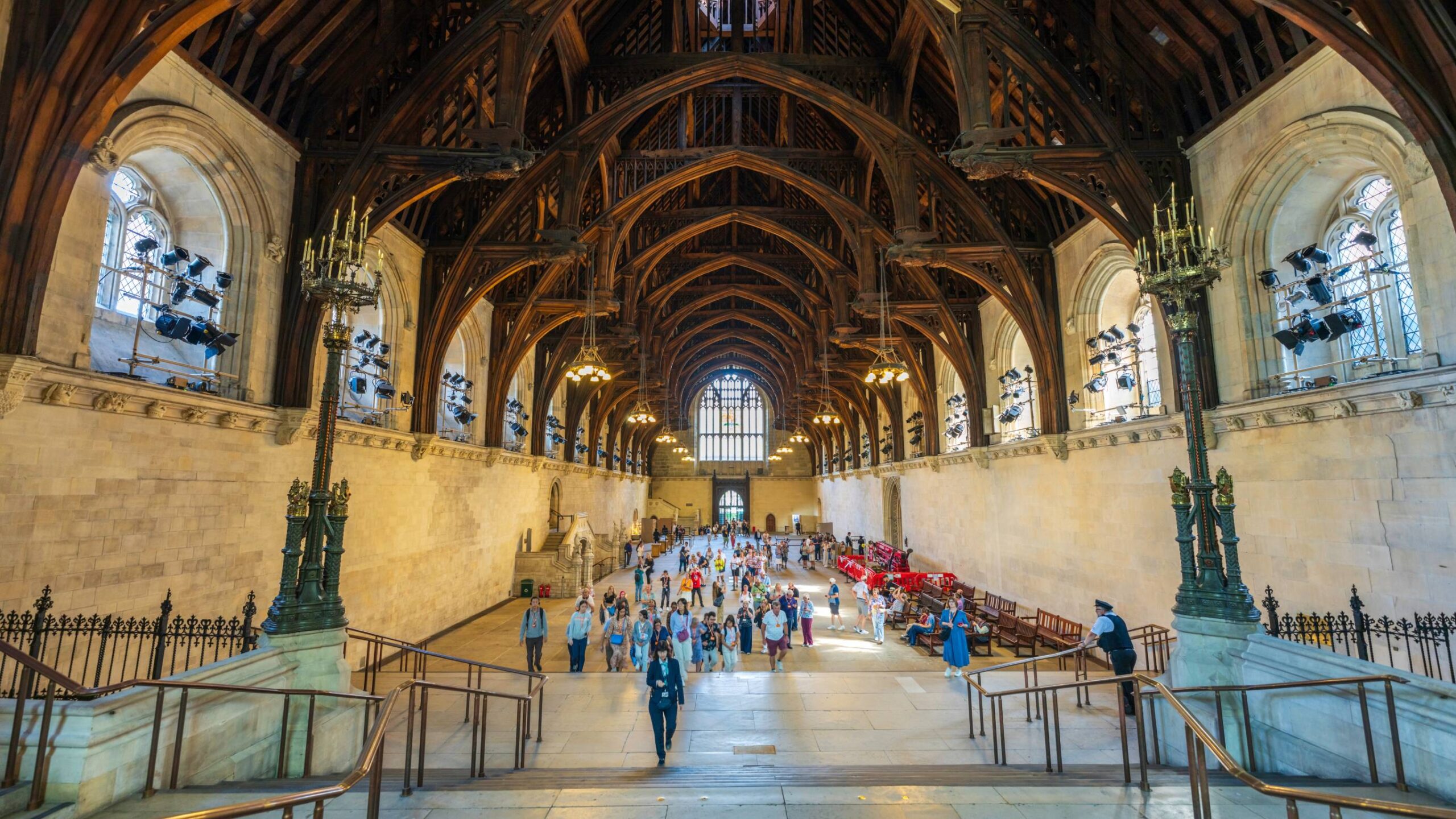

There has been a new parliamentary debate on a statutory duty of care for universities, which returned to Westminster Hall following a similar debate in 2023.

I had trouble finding some of the background material – it’s perhaps unfortunate that the Nottingham Trent webpage that was hosting all of the outputs and guidance notionally attached to the Higher Education Student Support Champion and the Department for Education’s Higher education mental health implementation taskforce now redirects to a picture and bio of new Trent VC Dave Petley.

It’s not at all clear why things like the guidance on Compassionate Communications or the National review of higher education student suicide deaths are, as a result, scattered across the internet, but there is almost certainly a metaphor in there somewhere.

Uncertainty

Opening the debate, Labour’s James Naish (Rushcliffe) argued that the current legal framework leaves “too much uncertainty for students and institutions alike”, noting a rise in students disclosing mental health conditions and confusion over what students can and can’t expect.

The law develops only after harm has occurred through costly and traumatic litigation brought by those least able to bear that burden.

Naish noted that a 2023 survey by the suicide prevention charity CALM found just 12 per cent of students believe their university handles mental health well, and referenced a British Medical Association survey of medical students published shortly before Christmas that called for a statutory duty, specifically citing concerns about sexism and sexual violence towards medical students.

Contributors shared harrowing constituency cases throughout the debate. Labour’s Llinos Medi (Ynys Môn) recounted the death of Mared Foulkes, a pharmacy student who died by suicide after receiving incorrect exam results from Cardiff University. Medi described the current situation as:

A postcode lottery in terms of quality and accessibility of mental health care.

Labour’s Lizzi Collinge (Morecambe and Lunesdale) described how Oskar, a student at Sheffield Hallam living with a brain injury, attempted suicide but his parents were never informed despite giving explicit consent for contact. Chadwick said the university later argued that this consent applied only to physical injuries, not to an attempt to take his own life. He proposed a practical safeguard:

Every student to nominate a trusted point of contact when they enrol, to be used in the event of a serious concern.”

Chadwick also highlighted data from the government’s National Review of higher education student suicide deaths, noting that reports were submitted for only 62 per cent of serious incidents, families were not involved in three quarters of investigations, and in 71 per cent of reports it was unclear whether there had been senior sign-off.

The DUP’s Jim Shannon (Strangford) highlighted that around 30 per cent of Northern Ireland students study on the UK mainland, making the issue directly pertinent to families in his constituency. He cited statistics on the prevalence of anxiety and mental health issues among young people in Northern Ireland and stressed:

Independence is not the same as isolation.

He called for discussions between the minister and the devolved administrations to work collectively across the United Kingdom.

Labour’s Warinder Juss (Wolverhampton West), a former personal injury solicitor, provided legal analysis, describing it as “quite shocking” that common law does not impose a duty of care on universities when such duties exist:

In prisons, hospitals, primary, secondary schools and colleges of further education… for doctor to patient, solicitor to client, manufacturer to consumer, and one road user to another.

She walked through the Abrahart v University of Bristol case in detail, and noted that had a duty of care existed:

There would have been a breach of that duty, and the university would consequently have been negligent.

A statutory duty, she argued, would “define expectations, embed accountability and promote prevention” while bringing UK law into line with the United States and Australia. She also pushed back on the idea that relying on the Equality Act is sufficient, noting that while some cases involve a history of engagement and diagnosis:

In many other cases, it could be something that the student suddenly finds himself in this situation.

Students without a formal disability diagnosis would fall through the gaps.

Labour’s Rachel Maskell (York Central) broadened the debate to include the intersection of pressures students face, and emphasised that students who struggle academically must always have “a second chance”.

Labour’s Tom Hayes (Bournemouth East) raised implementation questions, noting that any statutory duty would need clarity on what it means in a higher education context and must intersect with existing safeguarding responsibilities, health and safety law and equality legislation. He also asked:

Who would monitor and regulate compliance? Would it fall under Ofsted? Would it fall under the Office for Students, the DfE, or a new regulatory body?

Labour’s Mary Kelly Foy (City of Durham) highlighted the particular vulnerability of care-experienced and estranged students, citing a Unite Foundation report that “well over a quarter” face financial concerns that “directly damage their mental health”. She noted the scale of the increase in students disclosing mental health conditions since 2011, and argued that a statutory duty need not mean in loco parentis monitoring:

A professional standard of care providing the same level of protection that we would expect from an employer or a healthcare provider.”

A statutory duty would also provide clarity on data sharing to empower pastoral teams to involve emergency contacts without fearing that they are breaching GDPR – an issue raised repeatedly throughout the debate as universities have used data protection as a reason not to contact families. But Foy cautioned that concerns raised by the University and College Union must be addressed:

Simply imposing a duty of care on universities won’t work if already overstretched staff and underfunded pastoral teams are simply expected to pick up the pieces.”

Labour’s Kerry McCarthy (Bristol East) raised the question of whether a statutory duty of care is the mechanism needed to bring smaller and less prominent higher education providers on board, or whether there might be another way to ensure consistency across the sector.

The Liberal Democrat spokesperson argued that the voluntary university mental health charter – to which just over 100 of 165 universities have signed up – must become more than an aspiration:

A voluntary aspiration must evolve to a rigorous accountability mechanism… with clear standards, regular independent assessment and consequences for non-compliance.

Conservative shadow spokesperson Nick Timothy (West Suffolk) acknowledged that while their party’s position on a statutory duty is not yet fully established, “we certainly need to do a lot better than we’re doing right now.” He also bolted on a bunch of stuff about freedom of speech.

The response

Responding for the government, Skills Minister Josh McAlister began by acknowledging “the profound pain” felt by families who have lost loved ones and paying tribute to the Abraharts’ “tireless work” and the families from the LEARN Network “who continue to work alongside us to drive change.” He was unequivocal that change was needed:

This government believes that change in this regard is needed.

He then outlined recent government actions, including publication of the National Review of higher education student suicides, the extension of the Higher Education Mental Health Implementation Taskforce with updated terms of reference published in December 2025, and the appointment of Steve West to replace Edward Peck Higher Education Student Support Champion. He emphasised that the taskforce’s priorities include:

Exploring the most effective mechanisms for holding the sector to account.

On NHS capacity, McAlister noted the government is “recruiting eight and a half thousand additional NHS mental health staff by the end of this Parliament” and said the taskforce would shortly publish a report showcasing five successful higher education and NHS partnerships. He urged universities not already in such partnerships:

…to study these models and explore how they can forge an approach that works for their local context.

Perhaps inevitably, McAlister stopped short of committing to a statutory duty of care. He repeated the argument that universities already have a general duty of care under common law to deliver educational and pastoral services “to the standard of an ordinarily competent institution” and are expected to act reasonably. He also pointed to existing protections under the Equality Act 2010, which requires reasonable adjustments for disabled students including those with mental health conditions, and said:

Where a severe or urgent condition is apparent, reasonable adjustments should be made without waiting for a formal diagnosis or medical evidence.

On why the government was not introducing a statutory duty, McAlister raised concerns about unintended consequences:

It is not just a question of drafting. It would require defining a minimum legal standard for universities, which risks becoming a ceiling rather than a floor.

…and warned that a statutory duty:

…could drive providers towards defensive compliance and litigation instead of focusing on what really matters, spotting problems early, making timely adjustments and learning from serious incidents.

He also noted that:

Almost all students are adults. Introducing a special statutory duty for them could be disproportionate when the evidence shows that students in higher education have a lower suicide rate than others in the same age in the general population.

McAlister was quick to add this was “not in any way to minimise the problem at universities” but to “highlight the need for a proportionate response that strikes the right balance.”

His conclusion offered continued engagement but no commitment to legislate:

We will continue to monitor the evidence, listen deeply to bereaved families and hold providers to account. But right now, the fastest and most effective route to support safer campuses is for universities to embed the recommendations from the National Review and best practice identified through the task force’s outputs.

Round in circles

McAlister’s rejection of a statutory duty rested on three key arguments – that adequate legal protections already exist, that a statutory duty risks becoming “a ceiling rather than a floor,” and that students have a lower suicide rate than their peers in the general population. But is he right?

McAlister’s assertion that universities already have a general duty of care under common law to deliver services “to the standard of an ordinarily competent institution” has been repeated by successive ministers since 2023, but its legal basis is questionable.

The source has been traced to an AMOSSHE policy breakfast blog published in 2015 – since deleted from its original website. When tested in court in Abrahart v University of Bristol, the judge found no relevant common law duty existed.

In Feder and McCamish v The Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama, the court found a limited duty only because the institution failed to follow its own voluntary procedures – it explicitly did not recognise any general duty to protect student welfare.

Freedom of Information requests seeking the legal authority for the government’s position have been refused under legal professional privilege. The government has never identified a court, judge, or case supporting its assertion. As one legal analysis noted, the government’s response “has no legal weight” – a view shared by the defendant’s own barrister in the Royal Welsh case.

McAlister warned that a statutory duty would drive “defensive compliance and litigation” rather than genuine care. But the behaviours critics fear – defensive reliance on process, fragmentation of responsibility, procedural rigidity, retrospective rather than proactive responses – are arguably already characteristic of the current voluntary system.

Universities operate through dense policy layers designed to manage liability rather than responsibility. The absence of clear accountability has not produced proactive care – it has produced risk management in which no one is clearly responsible when foreseeable harm occurs.

Bob Abrahart’s analogy with seatbelt legislation is fascinating – before the law changed, critics warned compulsory seatbelts would encourage passive compliance rather than active judgment. What actually happened was that the law reset baseline expectations, and culture followed. A statutory duty would not prevent universities exceeding minimum standards – it would ensure none falls below them.

You could make a raft of similar arguments, by the way, about harassment and sexual misconduct. But just yesterday in the House of Lords skills minister Jacqui Smith pointed to “unacceptable levels of sexual harassment and abuse of girls within our schools and universities,” and pointed to the recently introduced Office for Students regulatory requirements on harassment and sexual misconduct as steps towards creating safer campus environments and improving institutional accountability.

Why are regulatory requirements the answer on that issue, but a danger on this?

McAlister also noted that students have a lower suicide rate than others of the same age, suggesting a statutory duty would be “disproportionate.” But for many, the framing is misleading.

University students are not representative of their age group – they have passed academic and financial thresholds to reach higher education, and many with acute mental health challenges never arrive or leave when unwell. A lower rate among a pre-selected, relatively advantaged population is expected – that it is not dramatically lower should concern, not reassure.

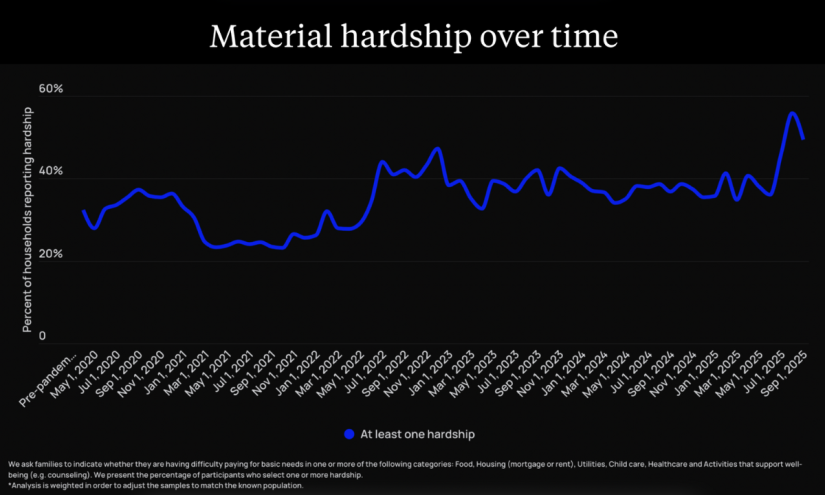

Universities are supposed to be semi-protected environments with pastoral care, support services, and trained staff. If the benchmark is whether students are safer inside higher education than outside it, the answer is far from clear. The reality of 160 deaths per year – more than three every week – hardly supports complacency.

Aggregate rates also conceal inequalities – male students die at more than twice the rate of female students, first-year undergraduates face significantly higher risk, and part-time students have higher rates than full-time peers.

Wait and see

The most prominent commitment Halfon made – that all universities would sign up to the mental health charter by September 2024 – was not achieved. Membership increased to 113 universities, covering approximately 90 per cent of students, but fell short of universal coverage.

More significantly, sign-up does not equal meaningful engagement – as of May 2025, only 17 institutions had actually been awarded charter status, and most of those achieved only “award with conditions.” The gap between signing up and embedding its principles illustrates a recurring pattern – outputs were produced, but outcomes remain elusive.

The National review of higher education student suicides was delivered – conducted by NCISH and published in May 2025. There is as yet no sign that engagement with its recommendations for universities will be even monitored, let alone action taken.

The Compassionate Communication Statement that Halfon promised was published and shared with the sector by December 2024, but adoption remains voluntary. There is no requirement for universities to follow it, and no sign even of monitoring that it’s been considered let alone implemented.

Plenty of SUs I’ve spoken to tell me that a) it’s never been considered formally inside their committee structures, and even where it has b) there’s been little on monitoring adoption across a university’s diverse departments. There has also c) been a sense in some universities that it doesn’t apply in some scenarios – like when a student is accused of an assessment offence, or being chased for tuition fee payments.

A Competency framework for non-specialist staff was published in February 2025, but it too is merely “advisory” – taskforce members raised concerns that because training is not mandatory, many staff groups may simply “opt out.”

Other commitments have stalled or failed entirely. Information sharing between schools and universities to identify at-risk students before arrival remains, in the taskforce’s own words, “a complex and time-consuming task.” UCAS has expressed “limited appetite” for changes to the reference process, and proposed “wellbeing passports” face significant cost and viability barriers.

Student analytics and early warning systems have not been rolled out – taskforce minutes show “major obstacles remain” and many providers feel they are “too far away” from implementation.

Guidance on restricting access to means of suicide was published in September 2024, but the national review found this was “rarely addressed” in university incident reports, with only one out of eight relevant reports recommending any action.

There’s also lots in the minutes on whether, how, if and so on there should be engagement with or compliance from FE providers, small and specialist, franchised and so on. Years abroad, placements and so on, not to much.

Crucially, the regulatory threat that underpinned Halfon’s approach has not materialised. He warned that if the sector response was unsatisfactory, he would ask the Office for Students to introduce a new registration condition on mental health. How would DfE even know?

What could be done?

As to how any duty might actually work, it’s not as if there aren’t some interesting examples that deserve further interrogation.

Sweden treats students as equivalent to employees for the purposes of workplace safety law. The Work Environment Act 1977 explicitly extends its protections to “persons undergoing education or training,” so university students are covered by the same statutory framework that protects workers.

The Higher Education Ordinance then reinforces this by requiring institutions to provide students with access to healthcare – “particularly preventive healthcare that aims to support students’ physical and mental health” – and a “good environment in which to study.”

What makes the Swedish system particularly robust is its enforcement through student representation. Student unions appoint studerandeskyddsombud (student safety representatives) who have formal statutory rights to participate in work environment activities.

These reps sit on safety committees alongside staff, participate in inspections of teaching premises, and can raise concerns about both physical and psychosocial study environments directly with university leadership. Universities have to provide training on work environment legislation, and the Swedish Work Environment Authority supervises compliance and can intervene against institutions.

Responsibility for the work environment lies with the institution and ultimately with the management – but students have formal standing to identify problems and demand action.

Meanwhile Australia embeds student wellbeing within a regulatory framework with real consequences. Domain 2 of the Higher Education Standards Framework includes a dedicated section on “Wellbeing and Safety,” requiring providers to promote a safe environment, provide timely advice on support services, and ensure services reflect student needs including mental health and wellbeing.

The Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA) has statutory powers to register providers, assess compliance, and take enforcement action. All providers must be registered, and registration must be renewed at least every seven years. Meeting wellbeing and safety standards is not optional – it is a condition of being permitted to operate.

Both models offer lessons. Sweden demonstrates that students can be brought within existing workplace safety legislation without creating unworkable burdens – the framework already exists for employees, and extending it to students is a matter of legal definition. Australia demonstrates that wellbeing requirements can be embedded in registration conditions enforced by an education regulator with powers to sanction non-compliance.

England already has the Office for Students as a sector regulator with power to impose registration conditions. The question ministers have repeatedly declined to answer is why wellbeing and safety in the learning environment should not be among them.

Both Sweden and Australia show this is not novel or untested – it is just how other comparable jurisdictions protect their students. Surely a Tertiary Professional Standard can’t be beyond the sector to meet?