Leslie Ortega is pursuing her second bachelor’s degree in botany at a university in California. She earned her first degree in business administration back in December 2016. That was before U.S. President Donald Trump took office. The experience was much different then.

“Obama was president when I was in college from 2012-2016 and I remember how happy everyone was around me,” Ortega said. “There was an oblivious feel to it where we felt safe. Now being in school I notice that there is definitely more fear in classrooms.”

With Trump in office for a second term, Ortega said she sees a major shift. It is no longer easy to be blind to the realities of how so many lives are changing.

“Existing in a world where your neighbor or your favorite food vendor can be snatched off the street on the basis of their skin color and occupation is impossible to hide from,” she said. “This has always been happening even during Obama but we had rose colored glasses when he was in office.”

As someone who recently graduated two months ago with a bachelor of arts focused in ethnic studies, I have to agree with Ortega. I cannot ignore the current political state of the country, especially as students and universities remain potential targets of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) raids.

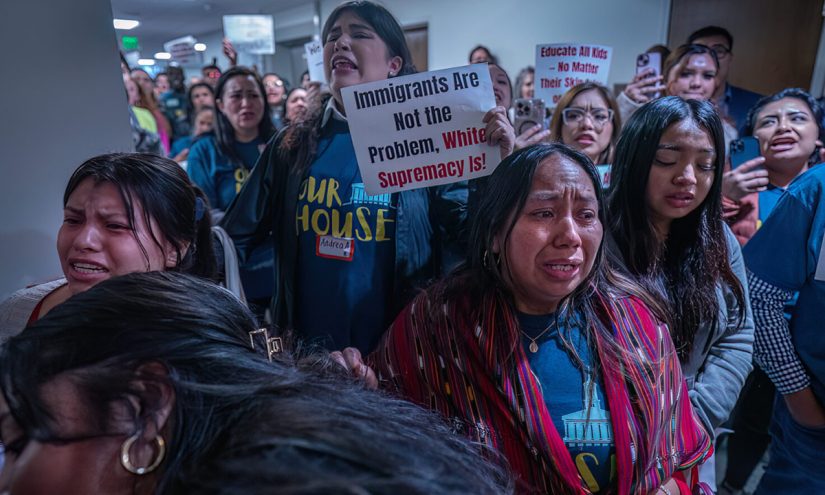

An attack on diverse perspectives

On top of that, conservatives are actively taking actions that threaten diversity, equity and Inclusion measures and certain subjects like critical race theory. My major, rooted in critical race theory, is deemed controversial by some because it teaches students to critically analyze information and question authority in a sense. Ethnic Studies courses are typically taught to engage people to uncover history from non-white perspectives, unveiling a legacy of imperialism and racism.

Actions that make it difficult to teach or learn these concepts are being enacted by people in power who seem to lack consideration for how marginalized communities will be affected.

At the California university I attended, two emails from the administration addressed the topic of immigration this past semester. The first was a letter from the interim president back in February 2025 which outlined guidance for university employees and students on how to interact with ICE officers if they ever showed up on campus.

It stated that since a large portion of the campus is open to the general public, it is therefore open to federal officers.

However, ICE agents could not enter areas not open to the public such as residence halls, confidential meeting rooms, employee offices or classrooms while the university was in session. This email also outlined resources students and staff could turn to such as the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights and a new center for “Dreamers” – undocumented people who had been brought into the United States as children. It also explained how to create an immigration preparedness plan.

A second email was sent out two months later, with quick guide cards and a link to an immigration resources page on the university website.

Will campus be an unsafe haven?

It is currently summer. How the university will actually respond if ICE were to show up on campus is really up in the air. It is one thing to voice concern and another to actually intervene in the face of injustice to protect targeted individuals.

While I will not return to campus this fall, I have no doubt that it will be students and staff of color who will ultimately serve as the first line of defense. Given how the university has responded in the past to student activist efforts, I would not be surprised if the campus administration did little should ICE arrive.

Across the country, university students have watched the detainment of student activists by ICE agents. Merely advocating against Israel’s ongoing genocide of the Palestinian people in Gaza, has been deemed a crime worthy of detention and deportation.

These detainees included Mohsen Mahdawi and Mahmoud Khalil from Columbia University and Rumeysa Ozturk from Tufts University. Khalil spent more than three months in detention before his release on 20 June.

The arrests of students simply for speaking out angers students like Ortega.

“It is infuriating to hear about student’s visas being revoked for their stance on supporting Palestine during a presidency that criminalizes opposition to the status quo,” Ortega said. “[This is] referring to anyone that critiques American ideology, the military complex or simply the American flag.”

Arrests in the City of Angels

Los Angeles has seen a surge of undocumented immigrants being arrested. According to the Los Angeles Times, nearly 2,800 people have been picked up by masked ICE agents on the streets, at job sites, Home Depot parking lots and even outside immigration court hearings since 6 June 2025.

Across the country these numbers could rise. In July, the U.S. Congress passed a national budget called the “Big Beautiful Bill” which will greatly increase the number of ICE agents and detention centers.

I view this bill as a way to cement discrimination against immigrants into the U.S. legal framework. We are already seeing the rapid construction and opening of detention centers such as Alligator Alcatraz in Florida – a tent city that can hold up to 3,000 people

According to public and internal data from the U.S. Customs and Border Protection agency, as collected by NBC News, more than 56,000 people were being held in ICE detention centers as of 1 Aug. 2025.

All this has created a state of fear. I spoke to someone who lives in California and currently holds a student visa holder. I’m not identifying the person because of fear that doing so will make them a target. The student recently earned a master’s degree in education and is currently in the admission process to a teaching credential program.

“There’s a culture here [in the U.S.] that when they hear that you don’t have a social security number, they stop helping you as if you were a pariah,” the person said. “I couldn’t work on campus, I lost a lot of opportunities because I didn’t have a social security number. Sometimes I could get stipends or fellowships but it was because of people who understand immigrants.”

Silencing of student activism

They now have a work visa and hope to get permanent residency, but given all the threats the current presidential administration has made to student visa holders, they wonder about their prospects.

“The silencing of the student activists is sending a message to everyone that if you dissent, if you protest, if you do not agree with what’s going on right now, then there will be consequences,” they said.

They said they used to be politically active, but no longer feel safe to do so here, or at least to the same degree.

“There’s an executive order that says that the first thing they’re going to look at about you is your social media, so you cannot even post about what you think, what you defend,” they said. “You cannot talk about the ongoing genocide anymore, because then, all the money that you have invested in changing your migratory status will be thrown to the trash. You give all your money, that’s dispossession without violence, you make this enormous sacrifice and then you don’t want to lose it, right, so you are forced, you are silenced.”

I am choosing to censor the person’s name for the sake of their own safety and wellbeing, I can’t help but wonder if doing so represents yet another way immigrants are silenced.

Fighting desensitization

All of this is to say that being a person of color and a student during this presidential administration has been exceptionally difficult. That’s particularly true for someone like Ortega, who attends school in a predominantly White area.

“It is emotionally and mentally draining to be focusing on your safety existing on a campus that doesn’t support you if you choose to wear a keffiyeh or a patch in opposition of a felon as a president,” Ortega said.

I recognize that as a person of color, I might not have the same advantages as someone who is White. As an American citizen though, I have some sense of protection in speaking up. But it is my Mexican and Guatemalan heritage that fuels my fight.

My existence is a result of immigration; I would not be where I am today if it were not for my family members who chose to come to the United States.

While it can be easy to become desensitized, especially with a new devastating headline every day, I urge others to hold onto some sense of hope by leaning into community resistance. Only by letting go of the belief that “this doesn’t personally affect me, so I don’t care” can we truly begin to dismantle systems of power.

Only seven months have passed since Trump returned to the presidential office. As he continues to carry out his seemingly racist agenda that targets anyone who is low-income, disabled, queer or non-White, university campuses that are supposed to be havens for learning and connecting with new ideas, are now filled with fear and suspense.

Questions to consider:

1. Why are increasing numbers of university students in the United States afraid to speak out?

2. Why do you think the author feels she doesn’t have the same protections as a U.S. citizen as someone who is White?

3. Do you think that people who want to study in another country should be able to do so?