Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

In September, The 74 published Robert Pondiscio’s opinion piece discussing how people without strong reading skills lack what it takes “to effectively weigh competing claims” and “can’t reconcile conflicts, judge evidence or detect bias.” He adds, “They may read the words, but they can’t test the arguments.”

To make his case, Pondiscio relies on the skill level needed to achieve a proficient score or better on National Assessment of Educational Progress, a level that only 30% of tested students reached on 2024’s Grade 8 reading exam. Only 16% of Black students and 19% of Hispanics were proficient or more.

Yet naysayers argue that the NAEP standard is simply set too high and that NAEP’s sobering messages are inaccurate. There is no crisis, according to these naysayers.

So, who is right?

Well, research on testing performance of eighth graders from Kentucky indicates that it’s Pondiscio, not the naysayers, who has the right message about the NAEP proficiency score. And, Kentucky’s data show this holds true not just for NAEP reading, but for NAEP math, as well.

Kentucky offered a unique study opportunity. Starting in 2006, the Bluegrass State began testing all students in several grades with exams developed by the ACT, Inc. These tests include the ACT college entrance exam, which was administered to all 11th grade public school students, and the EXPLORE test, which was given to all of Kentucky’s public school eighth graders.

Both the ACT and EXPLORE featured something unusual: “Readiness Benchmark” scores which ACT, Inc. developed by comparing its test scores to actual college freshman grades years later. Students reaching the benchmark scores for reading or math had at least a 75% chance to later earn a “C” or better in related college freshman courses.

So, how did the comparisons between Kentucky’s benchmark score performance and the NAEP work out?

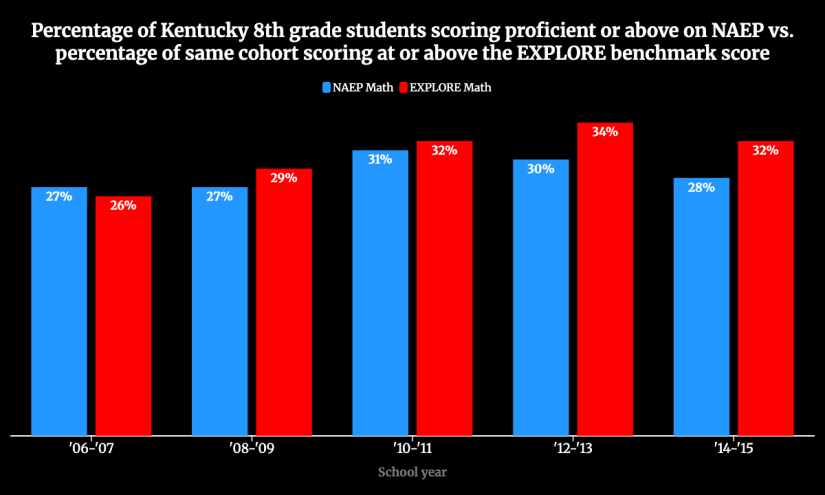

Analysis found close agreement between the NAEP proficiency rates and the share of the same cohorts of students reaching EXPLORE’s readiness benchmarks.

For example, in Grade 8 reading, EXPLORE benchmark performance and NAEP proficiency rates for the same cohorts of students never varied by more than four percentage points for testing in 2008-09, 2010-11, 2012-13 or 2014-15.

The same, close agreement was found in the comparison of NAEP grade 8 math proficiency rates to the EXPLORE math benchmark percentages.

EXPLORE to NAEP results were also examined separately for white, Black and learning-disabled students. Regardless of the student group, the EXPLORE’s readiness benchmark percentages and NAEP’s proficient or above statistics agreed closely.

Doing an analysis with Kentucky’s ACT college entrance results test was a bit more challenging because NAEP doesn’t provide state test data for high school grades. However, it is possible to compare each student cohort’s Grade 8 NAEP performance to that cohort’s ACT benchmark score results posted four years later when they graduated from high school. Data for graduating classes in 2017, 2019 and 2021 uniformly show close agreement for overall average scores, as well as for separate student group scores.

It’s worth noting that all NAEP scores have statistical sampling errors. After those plus and minus errors are considered, the agreements between the NAEP and the EXPLORE and ACT test results look even better.

The bottom line is: Close agreement between NAEP proficiency rates and ACT benchmark score results for Kentucky suggests that NAEP proficiency levels are highly relevant indicators of critical educational performance. Those claiming NAEP’s proficiency standard is set too high are incorrect.

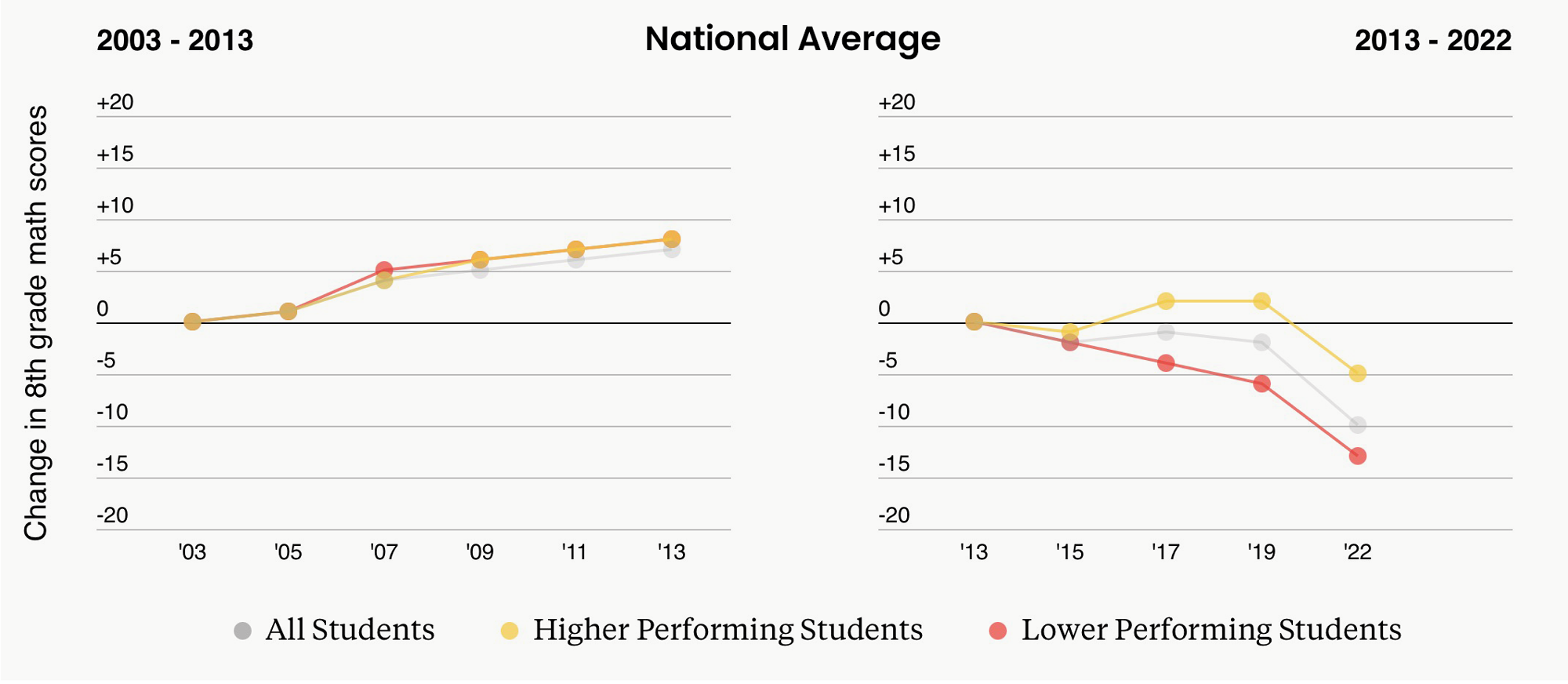

That leaves us with the realization that overall performance of public school students in Kentucky and nationwide is very concerning. Many students do not have the reading and math skills needed to navigate modern life. Instead of simply rejecting the troubling results of the latest round of NAEP, education leaders need to double down on building key skills among all students.

Did you use this article in your work?

We’d love to hear how The 74’s reporting is helping educators, researchers, and policymakers. Tell us how