For Americans under 35, the term “democratic socialism” triggers neither fear nor Cold War reflexes. It represents something far simpler: a demand for a functioning society. Younger generations have grown up in a world where basic pillars of American life—higher education, medicine, economic mobility, and even life expectancy—have deteriorated while inequality has soared. Democratic socialism, in their view, is not a fringe ideology but a practical response to systems that have ceased to serve the common good.

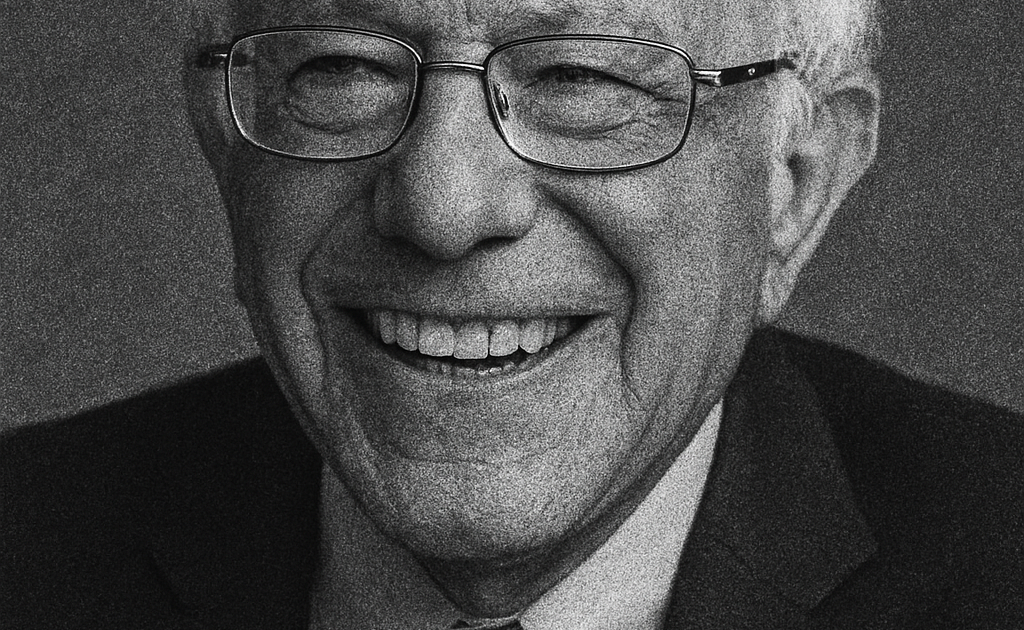

Nowhere is this clearer than in higher education. Millennials and Gen Z entered adulthood as universities became corporate enterprises, expanding administrative layers, pushing adjunct labor to the brink, and relying on debt-financed tuition increases to keep the machine running. Public investment collapsed, predatory for-profit chains proliferated, and nonprofit universities acted like hedge funds with classrooms attached. Students saw institutions with billion-dollar endowments operate as landlords and asset managers, all while passing costs onto working families. When Bernie Sanders called for tuition-free public college, young people did not hear utopianism—they heard a plan grounded in global reality, a model that exists in Germany, Sweden, Finland, and other social democracies that treat education as a public good rather than a revenue stream.

Healthcare tells an even harsher story. Americans under 35 watched their parents and grandparents navigate a system more focused on billing codes than care, one where an ambulance ride costs a week’s wages and a bout of illness can mean bankruptcy. They experienced the rise of corporatized university medical centers, private equity–owned emergency rooms, and insurance bureaucracies that ration access more cruelly than any state. They saw life-saving drugs priced like luxury goods and mental health services pushed out of reach. Compare this to nations with universal healthcare: longer life expectancy, lower infant mortality, and far less medical debt. Again, Sanders’ Medicare for All resonated not because of ideology but because young people recognized it as a plausible path toward the kind of humane medical system described by scholars like Harriet Washington, Elisabeth Rosenthal, and Mahmud Mamdani, who all critique the structural violence embedded in systems of unequal care.

Life expectancy itself has become a generational indictment. For the first time in modern U.S. history, it has fallen, driven by overdose deaths, suicide, preventable illness, and worsening inequities. Younger Americans know that friends and peers have died far earlier than their counterparts abroad. They see that countries with strong public services—childcare, unemployment insurance, housing supports, universal healthcare—live longer, healthier lives. They also see how austerity and privatization have hollowed out public health infrastructure in the United States, leaving communities vulnerable to crises large and small. The message is clear: societies that invest in people live longer; societies that treat health as a commodity do not.

Quality of Life (QOL) ties all of this together. People under 35 face rent burdens unimaginable to previous generations, debts that prevent them from forming families, stagnant wages, and a labor market defined by precarity. They face the erosion of public space, public transit, libraries, and social supports—what Mamdani would describe as the slow unraveling of the civic realm under neoliberalism. When they look abroad, they see countries with social democratic frameworks offering guaranteed parental leave, subsidized childcare, free or nearly free college, universal healthcare, and robust worker protections. These are not distant fantasies; they are functioning models that produce higher happiness levels, stronger social trust, and more stable democracies.

Older generations often accuse young people of radicalism, but the reality is the reverse. Millennials and Gen Z are pragmatic. They have lived through the failures of unfettered capitalism: historic inequality, monopolistic industries, soaring costs of living, and a political class unresponsive to their material conditions. They have read Sanders’ critiques of oligarchy and Mamdani’s analyses of state power and structural violence, and they see themselves reflected in those diagnoses. Democratic socialism appeals because it is rooted in material improvements to daily life rather than in abstract political theory. It promises a society where income does not determine survival, where education does not require lifelong debt, where parents can afford to raise children, and where basic health is not a luxury good.

People under 35 are not afraid of democratic socialism because they have already seen what the absence of a social democratic framework produces. They are not seeking revolution for its own sake. They are seeking a livable future. And increasingly, they view democratic socialism not as a radical break but as the only realistic path toward rebuilding public institutions, revitalizing democracy, and ensuring that future generations inherit a country worth living in.

Sources

Sanders, Bernie. Our Revolution: A Future to Believe In.

Sanders, Bernie. Where We Go from Here: Two Years in the Resistance.

Mamdani, Mahmood. Define and Rule: Native as Political Identity.

Mamdani, Mahmood. Neither Settler nor Native: The Making and Unmaking of Permanent Minorities.

Washington, Harriet. Medical Apartheid.

Rosenthal, Elisabeth. An American Sickness.

Skloot, Rebecca. The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.

Baldwin, Davarian. In the Shadow of the Ivory Tower.

Bousquet, Marc. How the University Works.