What’s the difference between academic writing and writing a news story? How different can they be?

I started out as a student of political science, became a journalist and then taught at university. Having started as an academic, you’d think returning to academic writing would be a snap. But it wasn’t.

As a journalist I’d been trained to say what needed to be said in as few words as possible. My writing needed to be easily read by anybody, regardless of their level of education and whether or not they read English as a first language. But academic writing is meant to impress. An essay is written by a student to impress a teacher, or a professor to impress colleagues or a tenure committee, or by a scientist or social scientist to impress a publisher.

Academic essays, reports and studies are meant to be ready by peers: people at the same or higher education level, who are experts in the same field of specialization and read them in their offices and classes.

News stories are meant to be read by anyone, sitting around the breakfast table as they munch on corn flakes.

You’d think the academic writing would be harder, no?

Telling stories

Imagine talking to a group of friends about something that happened in school. You don’t have to keep explaining who you are talking about or what you are talking about. They know all your references. But try telling the same story to your parents or better yet, adults who don’t know your school or community. It is a bit frustrating, because they don’t know what a stickler for rules Mr. Jackson is, or why most people avoid the third floor bathroom, or how so-and-so was dating you-know-who’s brother on the down low. You know, all that stuff that you need to know to understand why what happened at school was so significant.

It is much more difficult to tell a story when the person you are telling it to has no context. Moreover, when you write an essay or report you expect the person you are writing it for to read it. That’s their job. But no one is expected to read a news story.

As the author, you need to entice readers to choose your story to read. And you need to keep their attention throughout the story, because they aren’t obligated to read it to the end. So the story can’t be boring or tedious to read. Each paragraph has to have something interesting in it. It needs to be a good story worth reading.

I learned quickly as a journalist to read my stories out loud to myself. By doing so, I could hear when my writing was getting tired and dull. I could picture the person who is hearing the story fall asleep or walk away. When that happened I hit the delete button and started the paragraph again.

I would rethink whether the information I had included was really needed. Did my reader need to know that piece of data to understand what was happening?

Comparing academic and journalistic writing

To see the difference between journalistic and academic writing it is useful to look at a news story that came off of a report.

The news organization Vox published an article 17 December about a new report on poverty that was done by researchers at four California universities.

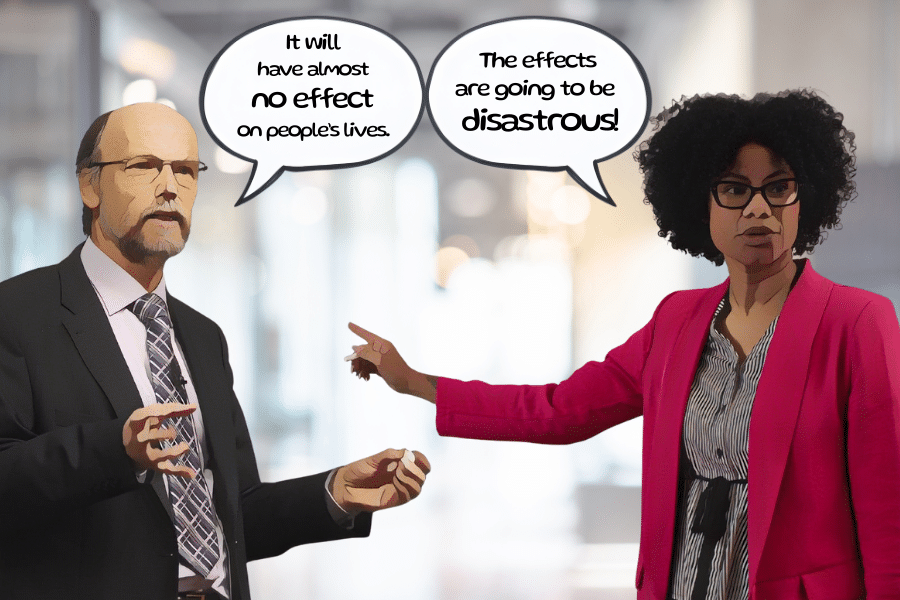

This is how the report began:

We study poverty minimization via direct transfers, framing this as a statistical learning problem while retaining the information constraints faced by real-world programs. Using nationally representative household consumption surveys from 23 countries that together account for 50% of the world’s poor, we estimate that reducing the poverty rate to 1% (from a baseline of 12% at the time of last survey) would cost $170B nominal per year.

Would you choose to read that with your corn flakes?

Here is how Vox reporter Sara Herschander begins the story:

When it comes to fixing the world’s worst problems, it’s easy to pretend that we’re helpless.

We tell ourselves that global poverty is just too big, too distant and too intractable an issue for us to solve. If the world could afford to solve it, or something like hunger, then surely somebody else would have done it already.

But, it turns out, that’s simply not true. According to a new report by a group of anti-poverty researchers that uses AI tools to achieve unusually granular data of the picture on the ground, the price tag for completely ending extreme poverty would be just $318 billion per year.

Writing that is clear and concise

The researchers didn’t worry that most people wouldn’t understand the terms “poverty minimization”, “direct transfers”, “statistical learning problem” or “information constraints”.

But try sticking those terms into a story you tell friends in the school hall and they’ll tune you out.

There is another big difference between news stories and academic essays and reports. Journalists don’t footnote sources. That’s because you wouldn’t have footnotes in a story you tell out loud. Just try it.

So instead, when a journalist needs to cite a source they write something like, “that’s according to data from the U.S. Census” or, “a recent study out of Harvard found that.” The journalist would likely hyperlink to the actual study for readers who might want to read it, as I did above for both the Vox article and the report. The idea is that the citation should be as short as possible and it should not break into the story.

The real challenge for a journalist is that the average reader has a very short attention span. Any break in a story is like an exit door. It is the chance for the reader to leave that depressing story about poverty to go to a more uplifting story about football or Bad Bunny.

The importance of revision

That’s why journalists write several drafts of a story before it gets published. In the first draft they just try to get all the information they have onto a page. In the second draft, they think about whether the information is needed and start taking things out and adding in others they might have forgotten. In the third, they try to close all those exit doors — all the places in the story that are tedious.

There are some tricks to doing this. It helps to round up or down numbers that have a lot of digits. A number like $1,569,345 is tedious to read. It takes 13 words to say it out loud. Instead, saying about $1.6 million will do the trick. That’s just five words out loud.

And it helps to use analogies and metaphors people can recognize. In a story I once wrote about the volatility of the stock market (doesn’t that sound like a yawner?) I likened the stock chart to Bart Simpson’s hair. For a story about an old technology company that kept getting sold and resold, I likened it to a secondhand sofa not moldy enough to toss into a skip.

But reaching for these analogies isn’t easy; it takes a little extra time and mental effort. In some ways journalists are translators. In general, translators take something in one language and turn it into another — from Japanese to English, for example. A journalist takes something from the language of the boring and tedious and obscure and turns it into the language of interesting and understandable.

It’s kind of like a jigsaw puzzle. You start with a bunch of pieces that seem to make little sense, but if you put them together in the right way you get a clear picture from it. But sometimes to do that you have to keep moving the different pieces around and sometimes you find you have to undo an entire section because something just doesn’t fit.

The result, when you are done, though, is pretty satisfying.

Questions to consider:

1. Why are news stories so different from essays?

2. In what ways are journalists translators?

3. What do you think makes a story interesting to read or hear?