The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) released its annual stat fest, Education at a Glance (EAG), two weeks ago and I completely forgot about it. But since not a single Canadian news outlet wrote anything about it (neither it nor the Council of Ministers of Education, Canada saw fit to put together a “Canada” briefing, apparently), this blog – two weeks later than usual – is still technically a scoop.

Next week, I will review some new data from the Programme for International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) that was released in EAG and perhaps – if I have time – some data from EAG’s newly re-designed section on tertiary-secondary. Today, I am going to talk a bit about some of the data on higher education and financing, and specifically, how Canada has underperformed the rest of the developed world – by a lot – over the past few years.

Now, before I get too deep into the data, a caveat. I am going to be providing you with data on higher education financing as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product. And this is one of those places where OECD really doesn’t like it when people compare data across various issues of EAG. The reason, basically, is that OECD is reliant on member governments to provide data, and what they give is not consistent. On this specific indicator, for instance, the UK data on public financing of higher education are total gibberish, because the government keeps changing its mind on what constitutes “public funding” (this is what happens when you run all your funding through tuition fees and student loans and then can’t decide how to describe loan forgiveness in public statistics). South Korea also seems to have had a re-think about a decade ago with respect to how to count private higher education expenditure as I recounted back here.

There’s another reason to be at least a little bit skeptical about the OECD’s numbers, too: it’s not always clear what is and is not included in the numbers. For instance, if I compare what Statistics Canada sends to OECD every year with the data it publishes domestically based on university and college income and on its own GDP figures, I never come up with exactly the same number (specifically, the public spending numbers it provides to OECD are usually higher than what I can derive from what is presumably the same data). I suspect other countries may have some similar issues. So, what I would remind everyone is simply: take these numbers as being broadly indicative of the truth, but don’t take any single number as gospel.

Got that? OK, let’s look at the numbers.

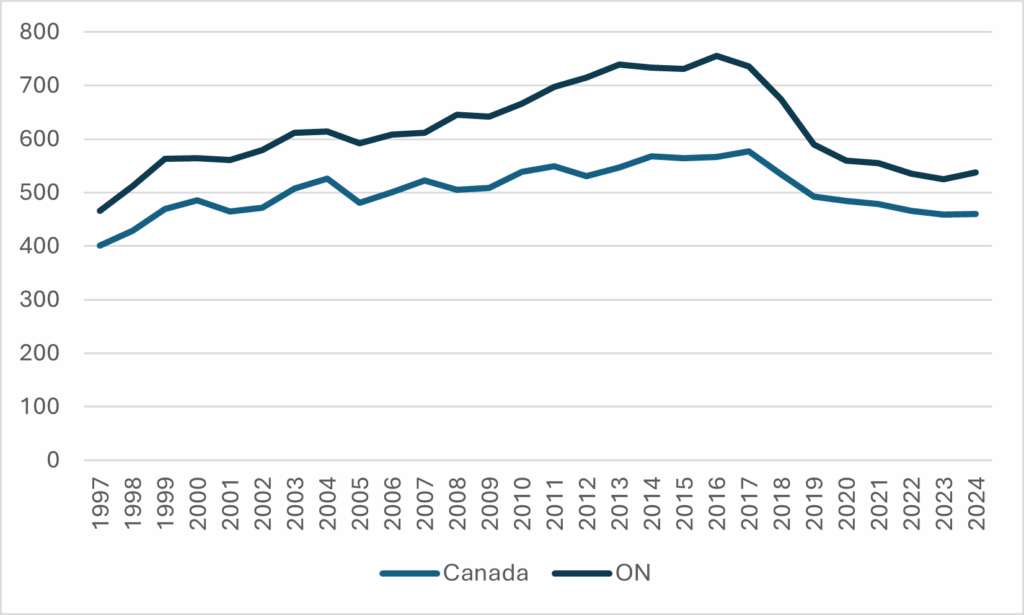

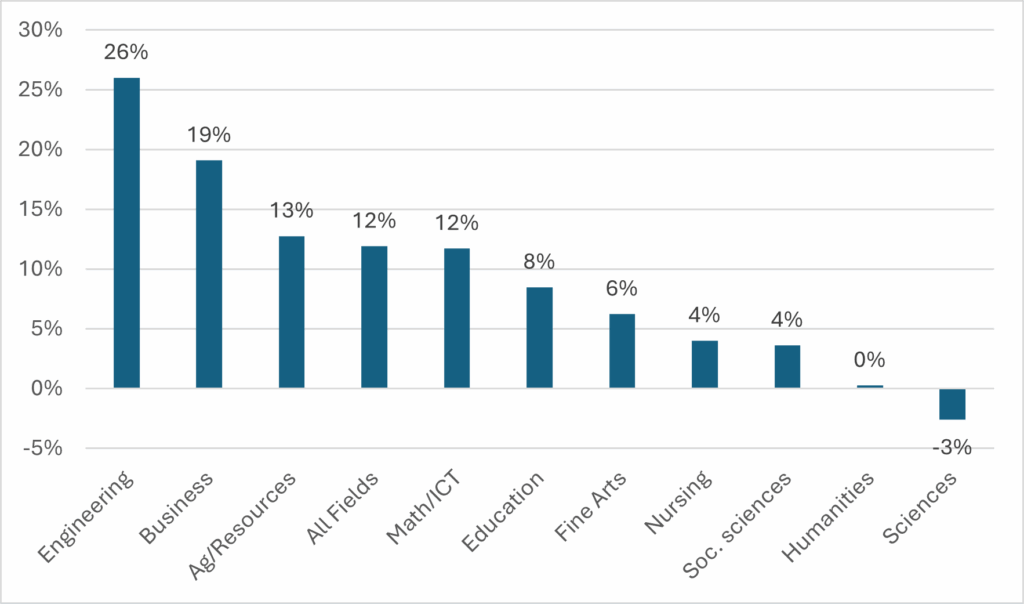

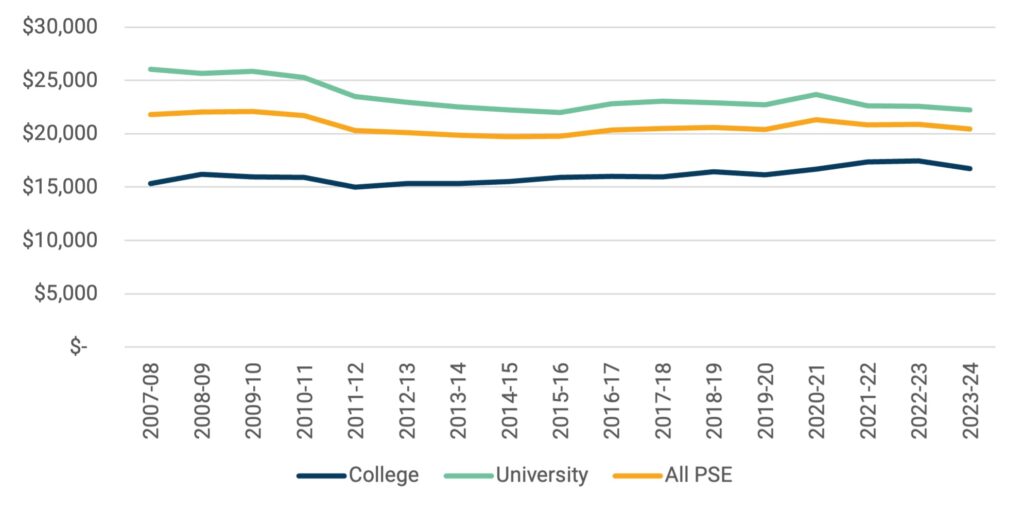

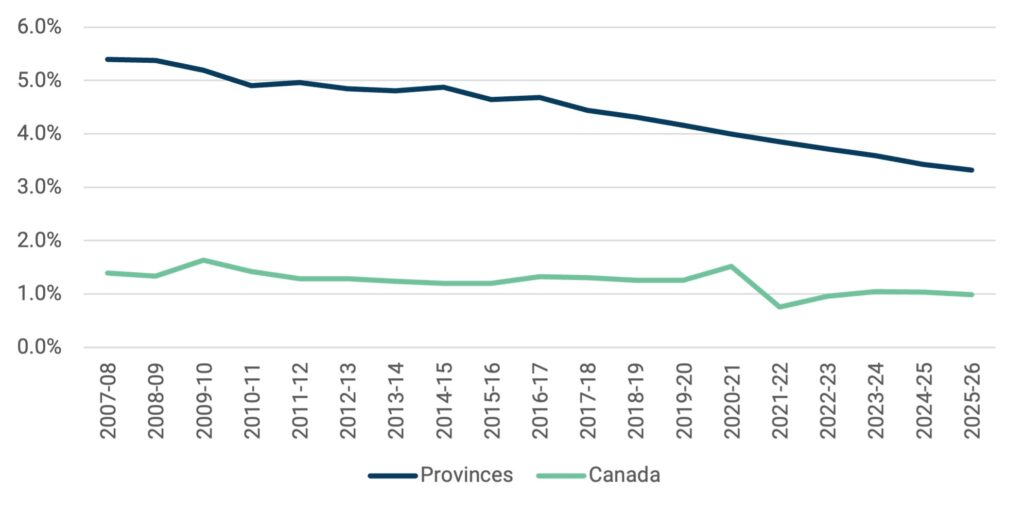

Figure 1: Public and Private Expenditure on Tertiary Institutions as a Percentage of GDP, Select OECD Countries, 2022

Canada on this measure looks…OK. Public expenditure is a little bit below the OECD average, but thanks to high private expenditure, it’s still significantly above the average. (Note, this data is from before we lost billions of dollars to a loss of international student fees, so presumably the private number is down somewhat since then). We’re not Chile, we’re not the US or the UK, but we’re still better than the median.

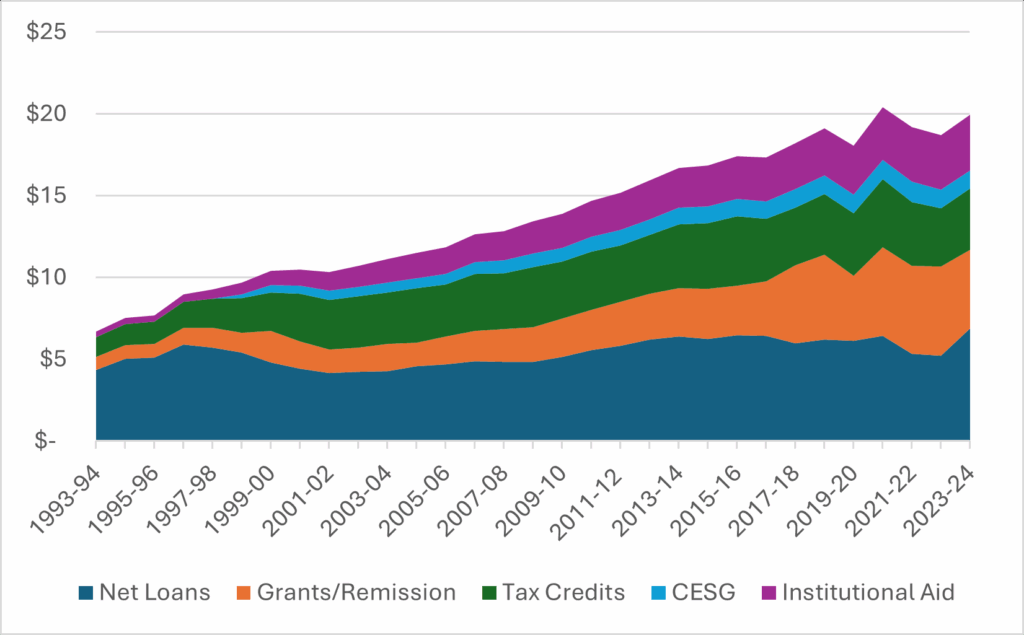

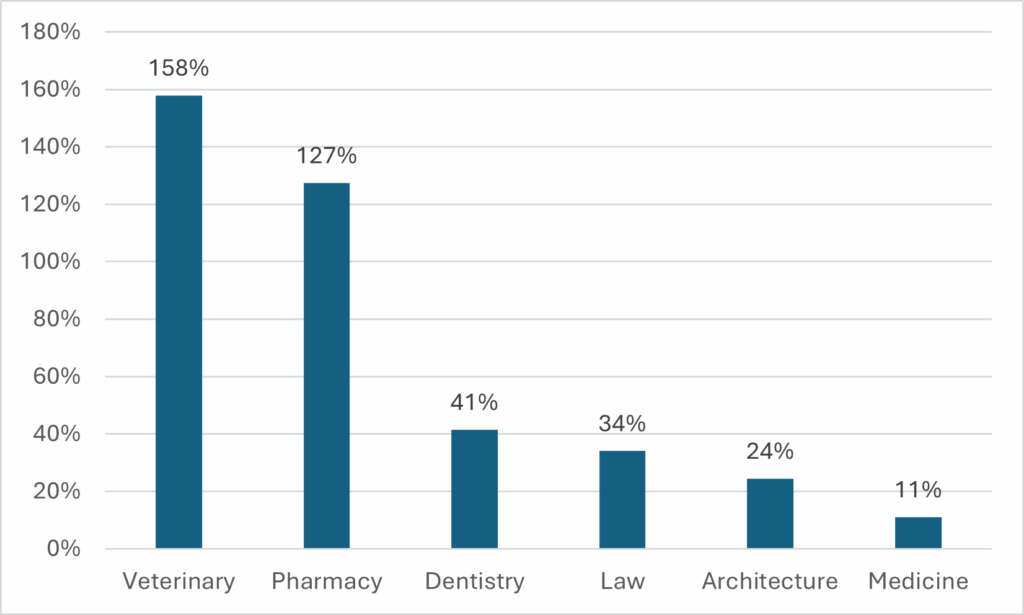

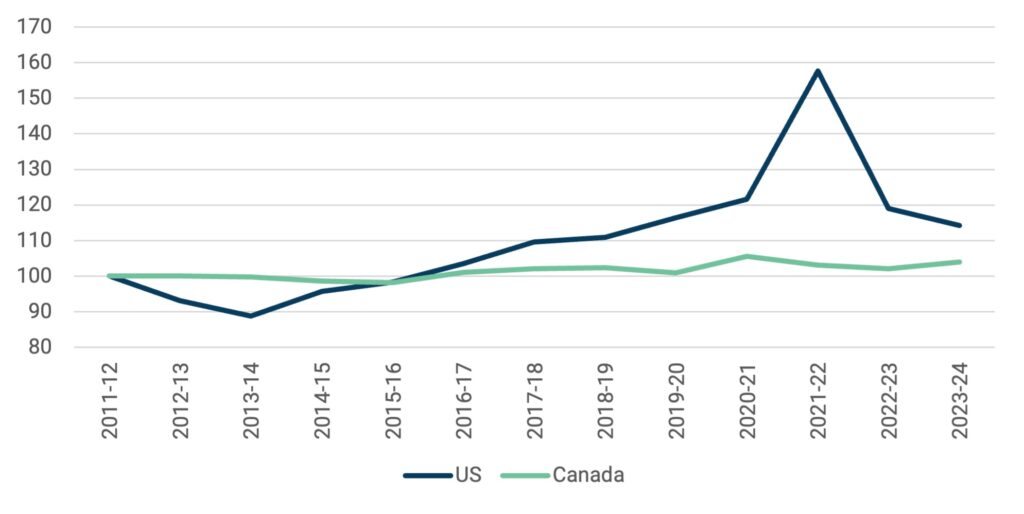

Which is true, if all you’re looking at is the present. Let’s go look at the past. Figure 2, below, shows you two things. First, the amount of money a country spends on its post-secondary education system usually doesn’t change that much. In most countries, in most years, moving up or down one-tenth of a percentage point is a big deal, and odds are even over the course of a decade or so, your spending levels just don’t change that much.

Figure 2: Total Expenditure on Tertiary Institutions as a Percentage of GDP, Select OECD Countries, 2005-2022

Second, it shows you that in both Canada and the United States, spending on higher education, as a percentage of the economy, is plummeting. Now, to be fair, this seems like more of a denominator issue than a numerator issue. Actual expenditures aren’t decreasing (much) but the economy is growing, in part due to population growth, which isn’t really happening in the same way in Europe.

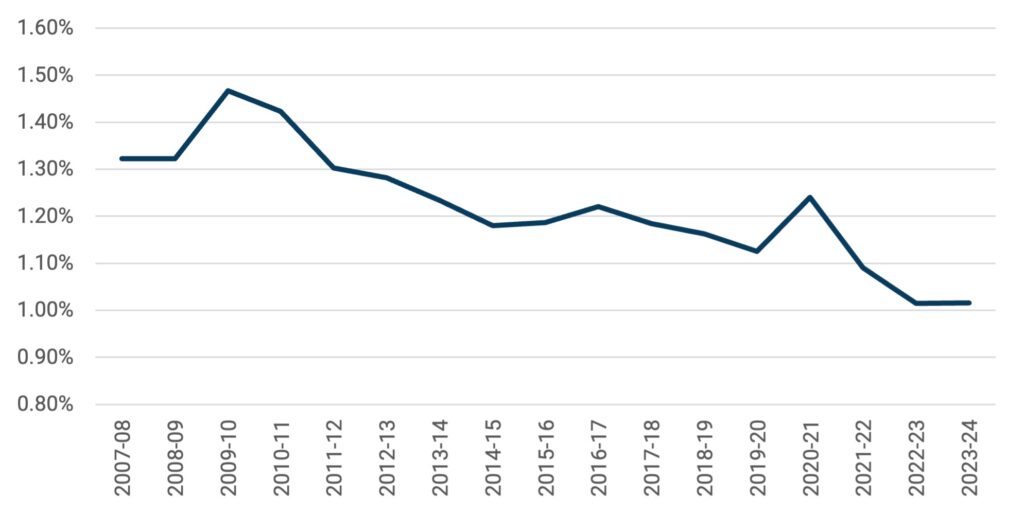

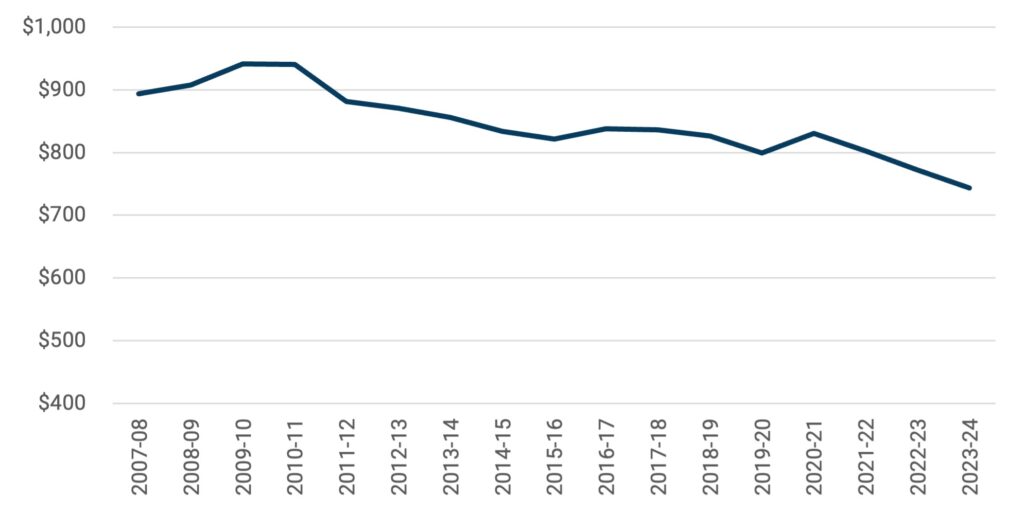

There is a difference between the US and Canada, though. And that is where the decline is coming from. In the US, it is coming (mostly) from lower private-sector contributions, the result of a decade or more of tuition restraint. In Canada, it is coming from much lower public spending. Figure 3 shows change in public spending as a percentage of GDP since 2005.

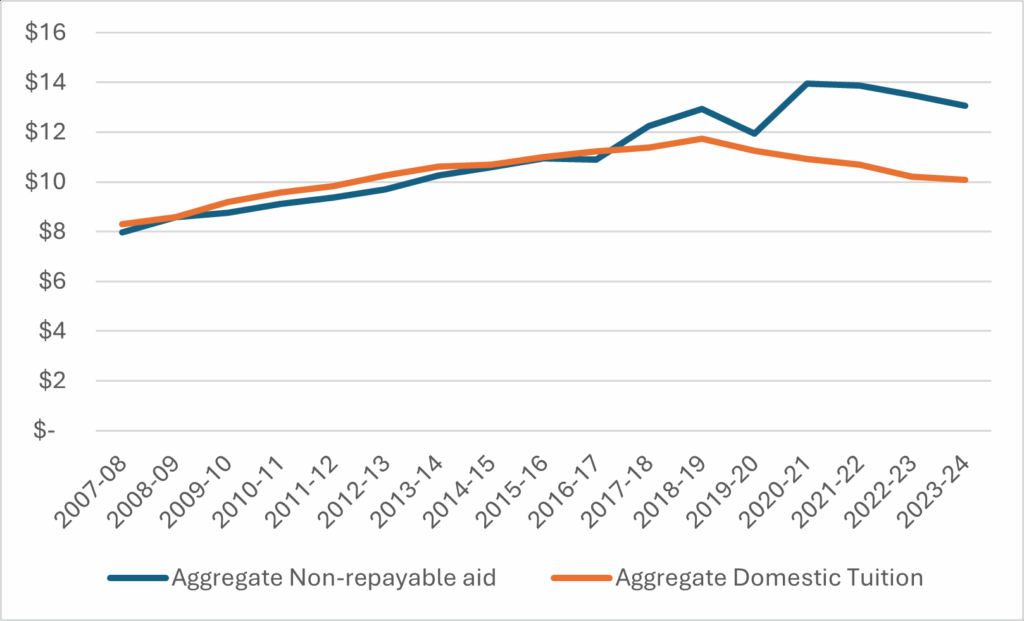

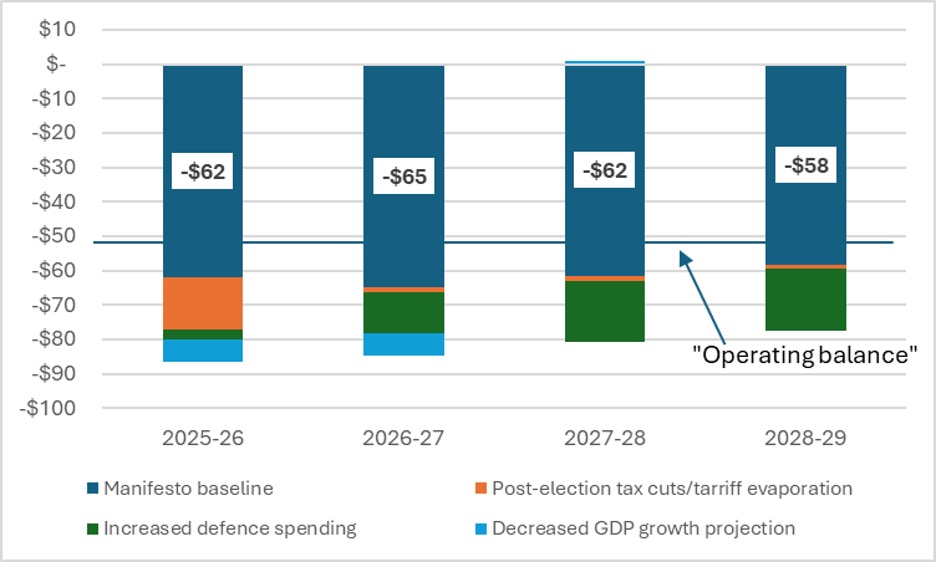

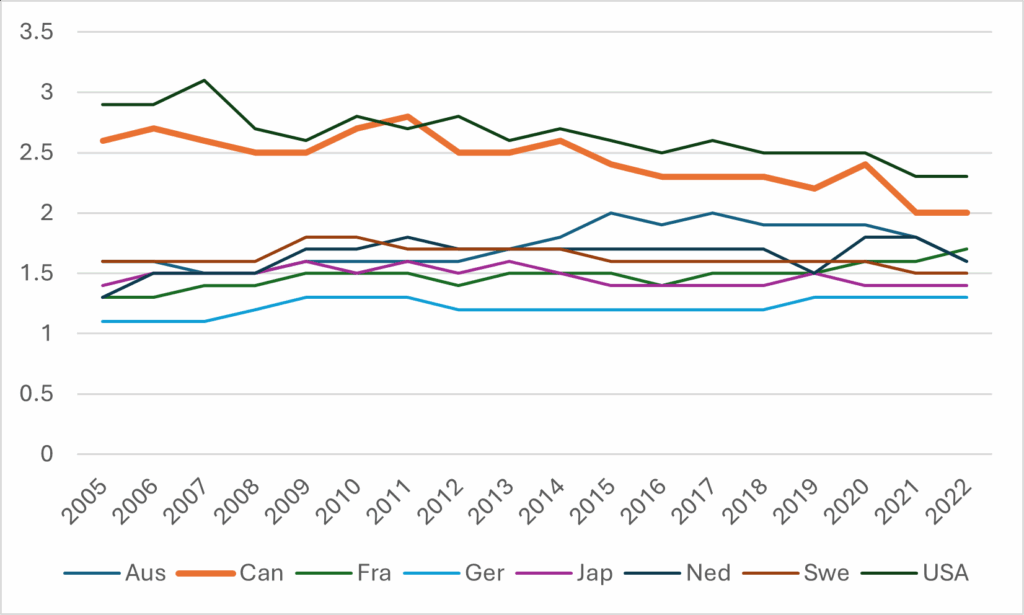

Figure 3: Change in Public Expenditure on Tertiary Institutions as a Percentage of GDP since 2005, Select OECD Countries, 2006-2022

As you can see here, few countries are very far from where they started in terms of spending as a percentage of GDP per capita. Australia and Sweden are both down a couple of tenths of a percentage point. Lucky Netherlands is up a couple of tenths of a percentage point (although note this is before the very large cutbacks imposed by the coalition government last year). But Canada? Canada is in a class all of its own, down 0.6% of GDP since just 2011. (Again, don’t take these numbers as gospel: on my own calculations I make the cut in public funding a little bit less than that – but still at least twice as big a fall as the next-worst country).

In sum: Canada’s levels of investment in higher education are going the wrong way, because governments of all stripes at both the federal and provincial level have thought that higher education is easily ignorable or not worth investing in. As a result, even though our population and economy are growing, universities and colleges are being told to keep operating like it’s 2011. The good news is that we have a cushion: we were starting from a pretty high base, and for many years we had international student dollars to keep us afloat. As a result, even after fifteen years of this nonsense, Canada’s levels of higher education investment still look pretty good in comparison to most countries. The bad news: now that the flow of international student dollars has been reduced, the ground is rising up awfully fast.