Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Since 2020, interest in homeschooling, microschooling, and other alternatives to conventional education has soared. Entrepreneurial parents and teachers have been building creative schooling options across the U.S. Kerry McDonald, a senior fellow at the Foundation for Economic Education and contributor to The 74, was so inspired by these everyday entrepreneurs that she wrote a book about them: Joyful Learning: How to Find Freedom, Happiness, and Success Beyond Conventional Schooling.The following is an adapted excerpt from McDonald’s book. It is reprinted here with permission from the publisher.

In 2019, I gave a keynote presentation at the Alternative Education Resource Organization’s (AERO) annual conference in Portland, Oregon. Founded in 1989 by Jerry Mintz, AERO has long supported entrepreneurial educators in launching new schools and spaces, with a particular focus on learner‑centered educational models. It was about a month after my previous book Unschooled was published, and I was talking about the gathering interest in unconventional education. Homeschooling numbers were gradually rising, and more microschools and microschooling networks were surfacing. I predicted that these trends would continue, but I said they would remain largely on the edge— as alternative education had for decades. They would offer more choices to some families who were willing to try new things, similar to those of us who eagerly embraced Netflix’s mailed DVDs when they first appeared. But I didn’t think these unconventional models would upend the entire education sector the way Netflix ultimately did with entertainment. I thought they would remain small and niche. I was wrong.

The COVID crisis catapulted peripheral educational trends into the mainstream, not only creating the opportunity for new schools and spaces to emerge but, more importantly, permanently altering the way parents, teachers, and kids think about schooling and learning. The pre‑pandemic tilt toward homeschooling and microschooling has converged with five post‑pandemic trends that are profoundly reshaping American education for families and founders. Together, these trends are shifting the K–12 education sector from being an innovation laggard to an innovation leader.

Trend #1: The growth of homeschooling and microschooling

The nearby microschool for homeschoolers that my children attended before COVID was one of only a sprinkling of schooling alternatives in our area. Now, it’s part of a wide, fast‑growing ecosystem of creative schooling options— both locally and nationally— representing an array of different educational philosophies and approaches. Families today are better able to find an education option that aligns with their preferences. From Maine to Miami to Missouri to Montana, the majority of the innovative schools and spaces I’ve visited have emerged since 2020, and many already have lengthy waitlists, inspiring more would‑be founders. The demand for these options will grow and accelerate over the next ten years, as will the number of homeschooling families, many of whom will be attracted to homeschooling as a direct result of these microschools and related learning models. Indeed, data from the Johns Hopkins University Homeschool Hub reveal that homeschooling numbers continued to grow during the 2023/2024 academic year compared to the prior year in 90 percent of the states that reported homeschooling data, shattering assumptions that homeschooling’s pandemic‑era rise was just a blip. Parents that otherwise wouldn’t have considered a homeschooling option will do so because homeschooling enables them to enroll at their preferred microschool or learning center.

One particularly striking and consistent theme revealed in my conversations with founders as I’ve crisscrossed the country is that their kindergarten classes are filling with students whose parents chose an unconventional education option from the start. These parents aren’t removing their child from a traditional school because of an unpleasant experience or a failure of a school to meet a child’s particular needs. They are opting out of conventional schooling from the get‑go, gravitating toward homeschooling and microschooling before their child even reaches school age. This trend is also likely to accelerate, as younger parents become even more receptive to educational innovation and change.

Trend #2: The adoption of flexible work arrangements

Today’s generation of new parents grew up with a gleeful acceptance of digital technologies and the breakthroughs they have facilitated in everything from healthcare to home entertainment. These parents see the ways in which technology and innovation enable greater personalization and efficiency, and expect these qualities in all their consumer choices. It’s no wonder, then, that parents of young children today are generally more curious about homeschooling and other schooling alternatives. They are often perplexed that traditional education seems so sluggish.

The response to COVID gave these parents license to consider other options for their children’s education. The school closures and extended remote learning during the pandemic empowered parents to take a more active role in their children’s education. That trend persists, as does the remaking of Americans’ work habits. The number of employees working remotely from home rather than at their workplace has more than tripled since 2019.

As more parents enjoy more flexibility in their work schedules, they will seek similar flexibility in their children’s learning schedules. While remote and hybrid work generally remain privileges of the so‑called “laptop class” of higher‑income employees, the growing adoption of flexible work and school arrangements is driving demand for more of these alternative learning models, including many of the ones featured in Joyful Learning that offer full‑time, affordable programming options for parents who don’t have job flexibility. Remote and hybrid work patterns are here to stay, and so is the trend toward more nimble educational models for all.

Trend #3: The expansion of school choice policies

The burst of creative schooling options since 2020 is now occurring all across the United States, in small towns and big cities, in both politically progressive and conservative areas, and in states with and without school choice policies that enable education funding to follow students.

Education entrepreneurs aren’t waiting around for politicians or public policy to green‑light their ventures or provide greater financial access. They are building their schools and spaces today to meet the mounting needs of families in their communities.

That said, there is little doubt that expansive school choice policies in many states are accelerating entrepreneurial trends. Founders I talk to who are developing national networks of creative schooling options, are intentional about locating in states with generous school choice policies that enable more parents to choose these new learning models. Other entrepreneurs are moving to these states specifically so that they can open their schools in places that enable greater financial accessibility and encourage choice and variety. Jack Johnson Pannell is one example. The founder of a public charter school for boys in Baltimore, Maryland, that primarily serves low‑income students of color, Jack grew discouraged that the experimentation that defined the early charter school movement in the 1990s steadily disappeared, replaced by an emphasis on standardization and testing that can make many—but certainly not all—of today’s charter schools indistinguishable from traditional public schools. He saw in the choice‑enabled microschooling movement the opportunity for ingenuity and accessibility that was a hallmark of the charter sector’s infancy. In 2023, Jack moved to Phoenix, Arizona, to launch Trinity Arch Preparatory School for Boys, a middle school microschool that families are able to access through Arizona’s universal school choice policies.

Trend #4: The advent of new technologies and AI

New technologies are also accelerating the rise of innovative educational models, while making it harder to ignore the inadequacies of one‑size‑fits‑all schooling. The ability to differentiate learning, personalizing it to each student’s present competency level and preferred learning style, has never been easier or more straightforward. It no longer makes sense to say that all second graders or all seventh graders should be doing the same thing, at the same time, in the same way—and failing them if they don’t measure up.

Emerging and maturing technologies help prioritize students over schools and systems, but the widespread introduction of artificial intelligence (AI) tools, and bots like ChatGPT, will hasten this repositioning. New AI bots can act as personal tutors for students, helping them navigate through their set curriculum. The real promise, according to founders focused more on agency‑ based or learner‑directed education, is for AI tools to work for the students themselves, helping them to control their own curriculum.

“We don’t have a set pathway for our learners. It’s personalized,” said Tobin Slaven, cofounder of Acton Academy Fort Lauderdale, which he launched with his wife Martina in 2021. Part of the global Acton Academy microschool network, Tobin’s school prioritizes student‑driven education in which young people set and achieve individual goals in both academic and nonacademic areas, participate in frequent Socratic group discussions, engage in collaborative problem‑solving and shared decision‑making, and embark on their own “hero’s journey” of personal discovery and achievement.

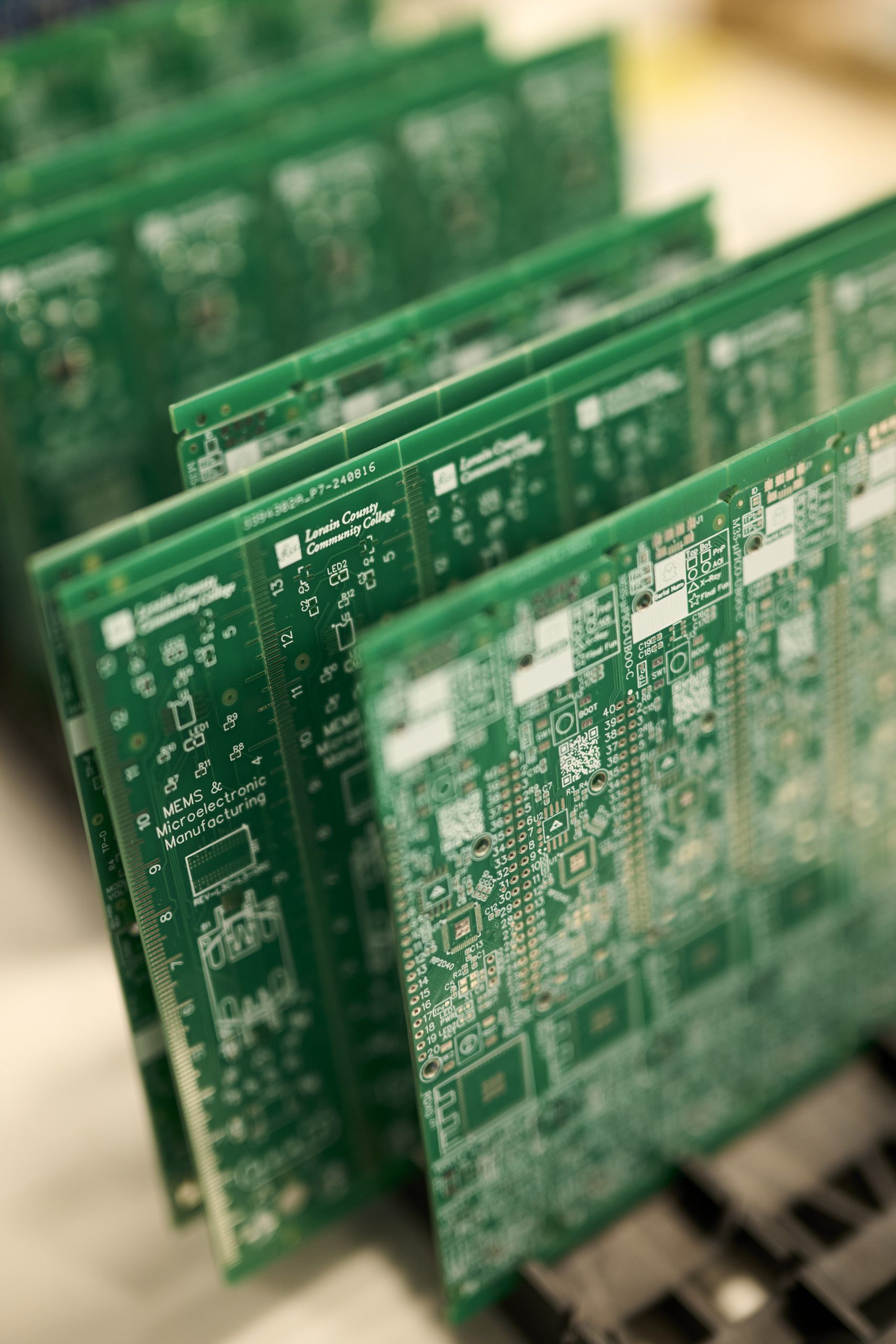

When we spoke in 2024, Tobin had recently founded an educational technology startup building AI companion tools that act as a personal tutor, life coach, and mentor all in one. He sees AI tools like his as being instrumental in helping learners have more independence and autonomy over their learning. Rather than AI bots guiding a student through a pre‑established curriculum, Tobin thinks the truly transformative potential of AI lies in tools that help students lead their own learning—answering their own questions and pursuing their own academic and nonacademic goals.

“When I hear the visions of some other folks in the education space, their visions are very different from mine,” Tobin said, referring to many of today’s emerging AI‑enabled educational technologies. He offered the example of a device known as a jig, used often in carpentry, to further illustrate his point. “The jig tells you exactly where the curves should be, where the cut should be. It’s like a template. The template that most of the AI folks are using is traditional education. It was broken from the start. It’s a bad jig,” Tobin said.

Instead, he sees the potential of AI to help reimagine education rather than reinforce a top‑down, traditional model. He is helping to create a new and better educational jig.

Trend # 5: Openness to new institutions

The final trend that is merging with the others to transform American education is the shift away from established institutions toward newer, more decentralized ones. Some of this is undoubtedly due to emerging technologies that can disrupt entrenched power structures and lead to greater awareness of, and openness to, new ideas, but the trend goes beyond technology. Annual polling by Gallup reveals that Americans’ confidence in a variety of institutions has fallen, with their confidence in public schools at a historic low. Only 26 percent of survey respondents in 2023 indicated that they had a “Great deal/Quite a lot” of confidence in that institution. The good news is that confidence in small business remains high, topping Gallup’s list with 65 percent of Americans expressing a “Great deal/Quite a lot” of confidence in that institution in 2023. The falling favor of public schools occurring at the same time that small businesses continue to be well‑liked creates ideal conditions for today’s education entrepreneurs. Families who are dissatisfied with public schooling may be much more interested in a small school or space operating or opening within their community.

For another signal of the shift away from older, more centralized institutions toward newer, more customized options, look at what the Wall Street Journal calls the “power shift underway in the entertainment industry,” as YouTube increasingly draws viewers away from traditional television networks. Individual YouTube content creators, such as the world’s top YouTuber, MrBeast, who has some 300 million subscribers, appeal to more viewers than the legacy media networks with their more curated content. New content creators are particularly attractive to younger generational cohorts like Gen Z, who prefer decentralized, user‑generated content over traditional, top‑ down media models. Consumers today are looking for more modern, responsive, personalized products and services, especially those being developed by individual entrepreneurs who bear little resemblance to legacy institutions. This is as true in education as it is in entertainment and will be an ongoing, indefinite, and transformational trend in both sectors.

Shortly before completing this manuscript, I spoke again at the annual AERO conference, this time in Minneapolis. Gone was my measured optimism of 2019. In its place was a mountain of evidence showing how popular alternative education models have become since 2020, and how steadily that popularity continues to grow. This isn’t a pandemic- era fad or an educational niche destined for the edges. This is a diverse, decentralized, choice‑filled entrepreneurial movement that is shifting American education from standardization and stagnation toward individualization and innovation.

We are only at the very early stages of a fundamental change in how, where, what, and with whom young people learn. Over the next decade, homeschooling and microschooling numbers will continue to grow, work flexibility will trigger greater demand for schooling flexibility, expanding education choice policies will make creative schooling options more accessible to all, AI and emerging technologies will help create a new “educational jig” fit for the innovation era, and declining confidence in old institutions will enable fresh ones to arise. The future of learning is brighter than ever. Families and founders are finding freedom, happiness, and success beyond conventional schooling, inspiring the growth of today’s joyful learning models and the invention of new ones yet to be imagined.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter